Abstract

Background: Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is a well-established treatment for severe obesity, yet its effects in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are not well understood. MBS in this population presents unique challenges, including the potential for exacerbating inflammatory disease activity and causing complications such as malnutrition and medication malabsorption. This study aims to assess the long-term outcomes of MBS in IBD patients, focusing on both metabolic outcomes and its impact on the course of IBD. Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 20 patients with IBD who underwent MBS at a tertiary center between 2005 and 2019. Data on baseline characteristics, surgical procedures, complications, weight loss, resolution of obesity-related diseases, and IBD-related outcomes were collected. Results: The cohort, primarily female (65%), had a mean preoperative body mass index (BMI) of 40.8 kg/m2. The MBS procedures performed were sleeve gastrectomy (n = 9), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (n = 6), one-anastomosis gastric bypass (n = 2), and Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding (n = 3). No major 30-day complications were recorded. At a median follow-up of 91 months, the mean BMI decreased by 9.5 kg/m2, with satisfactory outcomes in terms of resolution of obesity-related diseases. IBD activity scores increased postoperatively, particularly in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients, although these changes were not statistically significant. In addition, 30% of patients were hospitalized due to IBD exacerbation, and 15% required surgical intervention for IBD. Conclusions: MBS is an effective treatment for severe obesity and its related diseases in IBD patients. While encountering no major complications or mortality, some long-term complications were observed, with a possible increase in IBD activity, particularly in CD patients. Ongoing challenges, such as the risk of malnutrition, medication malabsorption, and postoperative IBD exacerbations, necessitate careful long-term follow-up.

1. Introduction

Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is considered the most effective treatment for patients with severe obesity [1]. Its popularity has increased rapidly since the beginning of the 21st century, and the indications for MBS were recently updated to include specific patient considerations [2,3]. The updated guidelines for MBS are for patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2, regardless of the presence, absence, or severity of obesity-related conditions. MBS should be considered in individuals with a BMI of 30–34.9 kg/m2 who do not achieve substantial or durable weight loss or improvement in obesity-related conditions with conservative methods. Along with the advantages of MBS, which include durable long-term weight loss, improvement and/or resolution of severe obesity-related conditions, and reduced mortality, there are chronic conditions that may be encountered postoperatively during patient follow-up, including insufficient weight loss/weight regain, reflux, malnutrition, and more. These may need further investigation and may even require revisional surgery. The development of these chronic complications could be related to many factors, including surgical technique, type of MBS (restrictive vs. hypo absorptive), and patient-related factors including age, gender, BMI, compliance with medical recommendations, and physical status. One area of practice, that remains uncertain, is MBS considerations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

IBD is a chronic condition with a multifactorial etiology, affecting approximately 0.5% of the Western population [4]. The two main subtypes of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). These diseases can range from mild to severely debilitating and may also cause malnutrition and cachexia. Patients may require multiple lines of medical and surgical treatment. Severe obesity rates among patients with IBD are increasing and range from 15% to 40% [5]. MBS in patients with IBD has been previously reported, and the type of procedure offered varied according to several factors, including BMI, disease severity and location, patient compliance, and more. However, there are many uncertainties and challenges in managing IBD patients before MBS, including determining the optimal surgical procedure, assessing the impact of MBS on IBD symptoms, and addressing the risks of both early and long-term complications, such as malnutrition and medication malabsorption, particularly with hypo-absorptive procedures.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of patients with IBD undergoing MBS. We hypothesize that these patients achieve satisfactory metabolic and nutritional outcomes, with no negative impact on the course of their IBD.

2. Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained patient database. All patients underwent MBS in a single tertiary university hospital between 2005 and 2019. Patients diagnosed with IBD prior to MBS were captured and made up the study cohort.

2.1. Patients

Data retrieved included patients’ baseline characteristics, including age, gender, BMI, previous MBS, and obesity-related medical conditions—diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HL), Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). IBD-related data included age at diagnosis, type of IBD (CD, UC, or indeterminate colitis IC), medical treatments prior to MBS, and prior surgical interventions for IBD. When available, Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) and Mayo score were recorded to denote the severity of symptoms in CD and UC, respectively. Perioperative data collected included the type of MBS performed, intraoperative complications, 30-day complications, length of stay, readmissions, and reoperations.

2.2. Surgical Technique

All procedures were performed laparoscopically using a standardized approach by one of the surgeons in the MBS unit. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (subcutaneous heparin, 5000 units) and antibiotic prophylaxis (intravenous cefazolin, 2–3 g) were routinely administered. The abdomen was insufflated using a Veress needle with carbon dioxide to a pressure of 15 mmHg, and at least five laparoscopic trocars were inserted. Technical steps for each procedure were adapted from a previous study [6] and are outlined below:

2.3. One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB)

Dissection was performed below the level of the crow’s foot at the lesser curvature of the stomach, extending to the lesser sac. A long and narrow gastric pouch was created using multiple linear stapler firings (Echelon -Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA or End-GIA Covidien/Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) guided by a 34–36 Fr bougie. The ligament of Treitz was identified, and the bowel was measured 180–200 cm distally. A linear stapled anastomosis was then performed between the gastric pouch and the jejunal loop, with the opening manually sutured using a barbed suture. A routine blue dye leak test was conducted.

2.4. Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG)

The greater curvature of the stomach was mobilized approximately 4 cm proximal to the pyloric sphincter, extending to the angle of His and exposing the left crus of the diaphragm. A 36–40 Fr bougie was used for calibration along the lesser curvature. The stomach was then transected using multiple linear staplers, and the specimen was removed through one of the working ports. Staple line reinforcement was not routinely used. A blue dye leak and patency test was performed.

2.5. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB)

A short gastric pouch was created using a linear stapler after dissection along the proximal lesser curvature, reaching the lesser sac. The ligament of Treitz was identified, and the bowel was transected 50–100 cm distally to create the bilio-pancreatic limb. Stapled gastrojejunal and jejunojejunal anastomoses were constructed, creating a 120–150 cm alimentary limb. In a case of conversion from Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding (LAGB), the band was removed during the procedure.

2.6. Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding (LAGB)

The gastrohepatic ligament was dissected at the pars flaccida of the lesser omentum, and a tunnel was created posterior to the stomach wall toward the angle of His. The band was introduced and locked anteriorly, then fixed with nonabsorbable sutures. The tube was tunneled to the left lateral abdominal wall, and the port was anchored to the fascia.

2.7. Follow-Up

Follow-up data included BMI and total weight loss (TWL) at the last visit. Resolution of obesity-related conditions (DM, HTN, and HL) was recorded (defined by cessation of medication). Data on chronic complications and reoperations related to MBS were also collected. IBD severity was recorded using the CDAI for CD and the Mayo score for UC, when available [7,8,9]. Data on hospitalizations, medications at last follow-up, and operations for IBD exacerbations were captured.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 29 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (range), as appropriate. Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentages). Differences between groups were assessed using Student’s t-test, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

2.9. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by our medical center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived by the IRB.

3. Results

During the study period, 20 patients with IBD underwent MBS at our center. These included 10 patients with CD, 9 with UC, and 1 with IC. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. The cohort predominantly consisted of women (65%) with a mean age of 40.3 ± 11.3 years and a mean BMI of 40.8 ± 4.0 kg/m2. One patient (5%) had a history of previous MBS. Prior to MBS, nine patients (45%) were on chronic medical treatment for IBD. At the time of MBS, the mean CDAI score for CD patients was 62.3 ± 35.7 (range 22–134), and the mean Mayo score for UC patients was 2.7 ± 2.4 (range 0–6).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

Operative and perioperative data are shown in Table 2. SG was performed in nine patients (45%), RYGB in six patients (30%), OAGB in two patients (10%), and laparoscopic LAGB in three patients (15%). There were no intraoperative complications or major 30-day complications. One patient (5%) required readmission due to dysphagia and dehydration with a gradual and spontaneous resolution.

Table 2.

Operative and perioperative data.

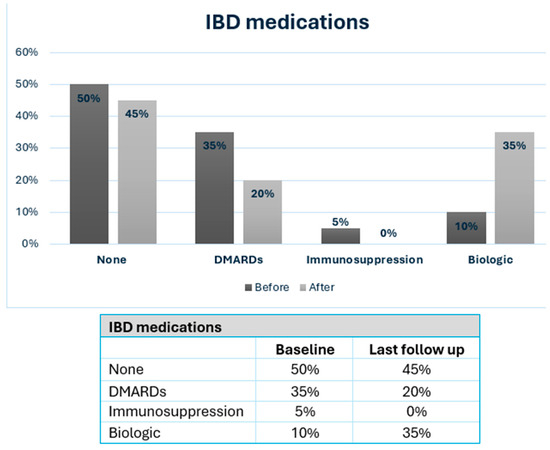

Long-term outcomes of MBS and IBD are detailed in Table 3, with a median follow-up of 91 months (mean 96.3 ± 41.1 months). The mean BMI at the last follow-up was 31.2 ± 7.3 kg/m2, reflecting a mean reduction of 9.5 ± 7.9 kg/m2. IBD-related outcomes were available in 14 patients (70% of cohort). At the last follow-up, 11 patients (55%) were on chronic medical treatment (Figure 1), 6 patients (30%) were hospitalized due to IBD exacerbations, and 3 patients (15%) underwent bowel resections related to IBD. The mean CDAI at follow-up was 135.2 ± 76.2 (range 46–269) vs. 62.3 ± 35.7 at baseline, (p = 0.055). The mean Mayo score for UC at last follow-up was 3.0 ± 1.6 vs. 2.7 ± 2.4 at baseline, (p = 0.411).

Table 3.

Long-term outcomes.

Figure 1.

IBD patients consuming medication at baseline and at last follow-up after MBS. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; DMARDs: Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs; MBS: metabolic and bariatric surgery.

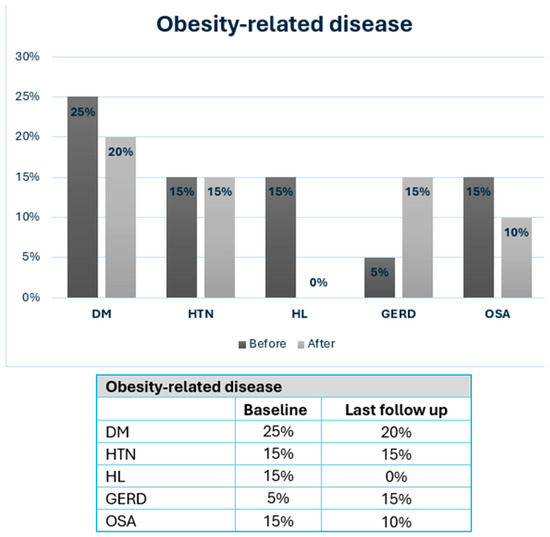

Obesity-related diseases at baseline and after MBS are shown in Figure 2. At last follow-up, four patients (20%) had DM, three patients (15%) had HTN, three patients (15%) had GERD, two patients (10%) had OSA, and none had hyperlipidemia. Chronic micronutrient deficiencies were present in 9 patients (45%) and included vitamin D deficiency (n = 4), iron deficiency (n = 6), B12 deficiency (n = 5), and 1 patient had severe protein energy malnutrition which required revision to normal anatomy after RYGB.

Figure 2.

Severe obesity-related disease in IBD patients at baseline and after MBS. MBS: metabolic and bariatric surgery; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; HL: hyperlipidemia; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea.

4. Discussion

In this case series with a review of the literature, we presented our experience with MBS in IBD patients. We observed that IBD activity scores increased after surgery, especially for CD patients, though this did not reach statistical significance. The mean CDAI for CD increased from 62.3 ± 35.7 to 135.2 ± 76.2 (p = 0.055), while the mean Mayo score for UC increased from 2.7 ± 2.4 to 3.0 ± 1.6 (p = 0.411). Although not reaching statistical significance, these changes coincided with increased therapeutic needs: the percentage of patients needing IBD medication increased from 50% to 55%, with 35% requiring biologic therapy (Figure 1). In addition, a significant minority of IBD patients required hospitalization (30%) or surgery (15%) for IBD exacerbation following MBS. The literature on MBS’s impact on IBD presents varying outcomes. Table 4 summarizes the published studies of MBS in IBD patients, highlighting both metabolic outcomes and the IBD disease course. Some studies reported exclusively favorable [10,11,12,13,14] or predominantly favorable results [15,16,17], while others have described more negative outcomes [18,19]. Most studies, however, described mixed effects of MBS on the clinical course of IBD [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. All studies consistently demonstrated favorable metabolic outcomes, measured by significant postoperative BMI reduction, TWL, or excess weight loss (EWL). A detailed description of all studies is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 4.

Review of studies describing outcomes of MBS on IBD.

Similar to these results, at a median follow-up of 91 months, we demonstrated meaningful metabolic improvements, with a mean BMI reduction of 9.5 + 7.9 kg/m2 and a mean last follow-up BMI of 31.2 ± 7.3 kg/m2, alongside a resolution or improvement in most obesity-related diseases (Figure 2). The prevalence of DM decreased from 25% to 20%, OSA decreased from 15% to 10%, and HL was completely resolved—findings consistent with previous reports in IBD patients [29].

Overall IBD symptoms worsened in the cohort throughout the study. We found a non-significant trend showing worsening symptoms in both UC and CD, measured by Mayo score and CDAI, respectively. We believe these findings are meaningful even though they were not statistically significant and could help in tailoring MBS to individual patients with IBD. The interplay between IBD and MBS is complex: while severe obesity exacerbates the inflammatory state in IBD through elevated pro-inflammatory adipokines [30] and altered gut microbiota, weight reduction can help mitigate these effects [10,20,21,22,23]. These mechanisms, combined with postoperative changes—including hormonal fluctuations, vitamin deficiencies, bacterial overgrowth, and altered intestinal epithelium—may also exacerbate existing IBD [31] or trigger de novo IBD [32,33]. Kiasat et al. [34] report an 80% increased risk of developing CD and 170% increased risk of developing unclassified IBD after RYGB, and an 80% increased risk of developing UC after SG. Similarly, Allin et al. [35] found an increased risk of de novo CD after MBS, particularly in women, but no association between MBS and UC. Conversely, Kochar et al. [36] reported a lower risk of de novo IBD after MBS, suggesting that effective severe obesity management through surgical or medical interventions might be associated with a reduced risk of developing de novo IBD compared to a control group.

Our findings underscore several challenges specific to the IBD population undergoing MBS. Postoperatively, 30% of patients were hospitalized due to IBD exacerbations, and 15% required surgical intervention due to IBD exacerbation. Chronic malnutrition and hypo-absorption of medications remain concerns as nine patients (45%) in our cohort had some form of malnutrition during follow-up, with one patient requiring MBS surgical revision. These findings emphasize the importance of stringent nutritional and clinical follow-up to address deficiencies in vitamins (e.g., B12, iron, and fat-soluble vitamins) and ensure the efficacy of IBD medications. Consistent with prior research, SG may offer a safer profile for IBD patients by minimizing risks of malabsorption while delivering effective weight loss outcomes [10,37], especially in CD patients [25].

When tailoring the most suitable MBS for IBD patients, some would recommend performing strictly restrictive procedures since these are possibly associated with fewer nutritional complications than hypo-absorptive procedures. In our study, most patients underwent SG (45%), followed by RYGB (30%), OAGB (10%), and LAGB (15%), with a good perioperative safety profile and no major complications. The cohort is too small to compare the MBS and IBD-related outcomes between different surgical procedures. In our opinion, when selecting the type of MBS, many factors should be taken into consideration, including age, BMI, IBD characteristics (type, location, behavior, and severity), route of absorption of IBD medications, prior IBD surgeries, remaining total small bowel length, and more. MBS should be individualized according to these factors. Larger cohort studies are needed to better define the correct approach for these patient populations.

This study has many limitations, including its retrospective design, small sample size representing a case series, variation in the types of MBS performed, and lack of a control group. We did not perform a comparative analysis between different types of MBS due to the low number of patients in each subgroup. In addition, 30% of patients were not available for long-term follow-up, which may skew the data. Despite these limitations, some strengths are worth mentioning, including a relatively long-term median follow-up of 91 months and the use of detailed indices for IBD severity, such as the CDAI and Mayo scores. These factors enhance the reliability and relevance of the findings, emphasizing the need for future prospective studies to clarify the long-term effects of MBS in IBD patients.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that MBS is a viable and effective treatment for patients with IBD and severe obesity, providing favorable metabolic outcomes with a potential, though not statistically significant, exacerbation of CD.

Despite these positive outcomes, the study highlights critical considerations for IBD patients, including the risk of postoperative complications such as IBD exacerbations, hospitalizations, and bowel resections, as well as the challenges associated with chronic malnutrition and hypo-absorption of medications, particularly in hypo-absorptive procedures. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate these results, optimize surgical approaches, and refine postoperative care strategies for this unique patient population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14020402/s1, Table S1. Review of studies evaluating MBS outcomes on IBD patients: detailed postoperative outcomes of bariatric surgery on IBD course.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-A. and J.B.Y.; Methodology, E.D.A. and L.O.; Software, J.B.Y. and L.O.; Validation, J.B.Y. and A.A.-A.; Formal Analysis, M.Z.; Investigation, A.A.-A.; Resources, A.A.-A. and M.Z.; Data Curation, E.D.A. and L.O.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.A.-A. and A.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.K. and J.B.Y.; Visualization, Y.K., A.A.-A., and J.B.Y.; Supervision, G.L.; Project Administration, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. All authors declare that they did not receive any funding or support for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (TLV-0252-24/date of approval 9 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

The IRB of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center approved a waiver of informed consent for all participating patients due to the retrospective design of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pipek, L.Z.; Moraes, W.A.F.; Nobetani, R.M.; Cortez, V.S.; Condi, A.S.; Taba, J.V.; Nascimento, R.F.V.; Suzuki, M.O.; Nascimento, F.S.D.; de Mattos, V.C.; et al. Surgery is associated with better long-term outcomes than pharmacological treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrisani, L.; Santonicola, A.; Iovino, P.; Palma, R.; Kow, L.; Prager, G.; Ramos, A.; Shikora, S. IFSO Worldwide Survey 2020-2021: Current Trends for Bariatric and Metabolic Procedures. Obes Surg. 2024, 34, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Shikora, S.A.; Aarts, E.; Aminian, A.; Angrisani, L.; Cohen, R.V.; De Luca, M.; Faria, S.L.; Goodpaster, K.P.; Haddad, A.; et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2023, 33, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviglia, G.P.; Garrone, A.; Bertolino, C.; Vanni, R.; Bretto, E.; Poshnjari, A.; Tribocco, E.; Frara, S.; Armandi, A.; Astegiano, M.; et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Population Study in a Healthcare District of North-West Italy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaazan, P.; Seow, W.; Yong, S.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Segal, J.P. The Impact of Obesity on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Abeid, A.; Dvir, N.; Lessing, Y.; Eldar, S.M.; Lahat, G.; Keidar, A.; Yuval, J.B. Primary Versus Revisional Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery in Patients with a Body Mass Index ≥ 50 kg/m2-90-Day Outcomes and Risk of Perioperative Mortality. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 2872–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.E.; Werida, R.H.; Radwan, M.A.; Askar, S.R.; Omran, G.A.; El-Mohamdy, M.A.; Hagag, R.S. Efficacy and safety of infliximab and adalimumab in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 3259–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoepfer, A.M.; Beglinger, C.; Straumann, A.; Trummler, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; E Bruegger, L.; Seibold, F. Fecal calprotectin correlates more closely with the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) than, C.R.P.; blood leukocytes the, C.D.A.I. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Panaccione, R.; Chen, L.; Peterson, S.; Mcconnell, J.; Baudhuin, L.; Hanson, K.; Feagan, B.G.; Harmsen, S.W.; et al. Relationships between disease activity and serum and fecal biomarkers in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 6, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Hashash, J.G.; Baker, G.; Farraye, F.A.; Waghray, N.; Kochhar, G.S. Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Disease Outcomes in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A US-based Propensity Matched Cohort Study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 58, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidemann, L.; Dietrich, A. Newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease, and hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma in a bariatric surgery patient-dealing with the complexity of obesity-associated diseases: A case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 17, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.L.; Barnes, E.L.; Herfarth, H.H.; Isaacs, K.L.; Jain, A. Bariatric Surgery Is a Safe and Effective Option for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2019, 3, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honoré, M.; McLeod, G.; Hopkins, G. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in Crohn’s disease patients: An initial Australian experience. ANZ J. Surg. 2018, 88, E708–E712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, B.; Kopylov, U.; Goitein, D.; Lahat, A.; Bardan, E.; Avidan, B.; Lang, A.; Maor, Y.; Eliakim, R.; Ben-Horin, S. Severe and morbid obesity in Crohn’s disease patients: Prevalence and disease associations. Digestion 2013, 88, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, N.P.; Habermann, E.B.; Sada, A.; Kellogg, T.A.; McKenzie, T.J. Is Bariatric Surgery Safe and Effective in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Obes Surg. 2020, 30, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, F.; Rizzi, A.; Ferrari, C.; Frontali, A.; Casiraghi, S.; Corsi, F.; Sampietro, G.M.; Foschi, D. Bariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: An accessible path? Report of a case series and review of the literature. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aelfers, S.; Janssen, I.M.C.; Aarts, E.O.; Smids, C.; Groenen, M.J.; Berends, F.J. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Not a Contraindication for Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbière, L.; Scanff, A.; Desfourneaux, V.; Merdrignac, A.; Ingels, A.; Thibault, R.; Bouguen, G.; Bergeat, D. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease from a French nationwide database. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moum, B.; Jahnsen, J. Fedmekirurgi ved inflammatorisk tarmsykdom [Obesity surgery in inflammatory bowel disease]. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2010, 130, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Márquez, M.; Frutos Bernal, M.D.; Ruiz de Gordejuela, A.G.; García-Redondo, M.; Millán, M.; Sabench Pereferrer, F.; Tarascó Palomares, J.; Grupo ReNacEIBar. Results of the national registry of patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease candidates for bariatric surgery (ReNacEIBar). Cir. Esp. 2024, 102, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga Neto, M.B.; Gregory, M.H.; Ramos, G.P.; Bazerbachi, F.; Bruining, D.H.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Kushnir, V.M.; E Raffals, L.; A Ciorba, M.; Loftus, E.V.; et al. Impact of Bariatric Surgery on the Long-term Disease Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminian, A.; Andalib, A.; Ver, M.R.; Corcelles, R.; Schauer, P.R.; Brethauer, S.A. Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lascano, C.A.; Soto, F.; Carrodeguas, L.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.J.; Wexner, S.D. Management of ulcerative colitis in the morbidly obese patient: Is bariatric surgery indicated? Obes. Surg. 2006, 16, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reenaers, C.; de Roover, A.; Kohnen, L.; Nachury, M.; Simon, M.; Pourcher, G.; Trang-Poisson, C.; Rajca, S.; Msika, S.; Viennot, S.; et al. Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-Control Study from the GETAID. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, K.; Lo, T.; Tavakkoli, A.; Sheu, E. Short-Term Outcomes of Inflammatory Bowel Disease after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs Sleeve Gastrectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 893–901.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raziel, A.; Aminov, R.; Sakran, N.; Goitein, D. Bariatric surgery and Crohn’s disease. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 2, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; McCarty, T.R.; Njei, B. Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Outcomes of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Inpatient Sample Analysis, 2004–2014. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keidar, A.; Hazan, D.; Sadot, E.; Kashtan, H.; Wasserberg, N. The role of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.; Khan, S. Systematic review: Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and de-novo IBD development after bariatric surgery. Surgeon 2023, 21, e71–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabeza, R.M.; Vadlakonda, A.; Chervu, N.; Ebrahimian, S.; Sakowitz, S.; Yetasook, A.; Benharash, P. Short-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A national analysis. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Koenen, B.; Kirby, D.F. Bariatric Surgery and Its Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermansaravi, M.; Valizadeh, R.; Farazmand, B.; Mousavimaleki, A.; Taherzadeh, M.; Wiggins, T.; Singhal, R. De Novo Inflammatory Bowel Disease Following Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 3426–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holinger, C.; Skidmore, A. Case report: Gastric sleeve surgery leads to new onset Crohn’s disease. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiasat, A.; Granström, A.L.; Stenberg, E.; Gustafsson, U.O.; Marsk, R. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2022, 18, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allin, K.H.; Jacobsen, R.K.; Ungaro, R.C.; Colombel, J.-F.; Egeberg, A.; Villumsen, M.; Jess, T. Bariatric Surgery and Risk of New-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis. 2021, 15, 1474–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, G.S.; Desai, A.; Syed, A.; Grover, A.; El Hachem, S.; Abdul-Baki, H.; Chintamaneni, P.; Aoun, E.; Kanna, S.; Sandhu, D.S.; et al. Risk of de-novo inflammatory bowel disease among obese patients treated with bariatric surgery or weight loss medications. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Mohan, B.P.; Ponnada, S.; Singh, A.; Aminian, A.; Regueiro, M.; Click, B. Safety and Efficacy of Bariatric Surgery in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3872–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).