The Multifactorial Burden of Endometriosis: Predictors of Quality of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Statistical Analysis

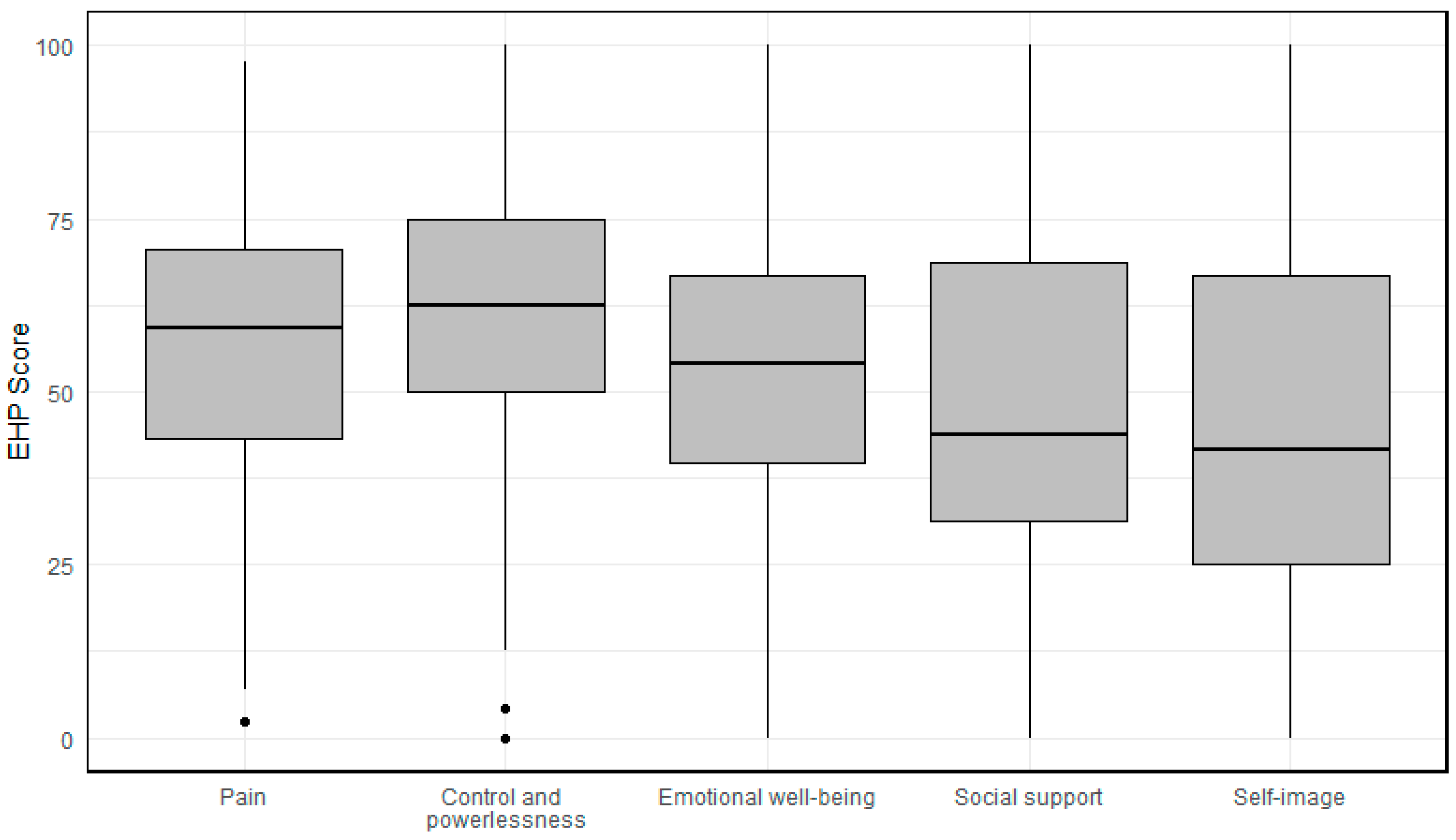

3. Results

3.1. Pain

3.2. Control and Powerlessness

3.3. Emotional Well-Being

3.4. Social Support

3.5. Self-Image

3.6. Summary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium. Reprint of: Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: A multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112 (Suppl. S1), e137–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchin, F.; Barbara, G.; Saita, E.; Mosconi, P.; Roberto, A.; Fedele, L.; Vercellini, P. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and mental health: Pelvic pain makes the difference. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 36, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri Kigloo, H.; Itani, R.; Montreuil, T.; Feferkorn, I.; Raina, J.; Tulandi, T.; Mansour, F.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Suarthana, E. Endometriosis, chronic pain, anxiety, and depression: A retrospective study among 12 million women. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 346, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuffaro, F.; Russo, E.; Amedei, A. Endometriosis, Pain, and Related Psychological Disorders: Unveiling the Interplay among the Microbiome, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress as a Common Thread. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, K.D.; Seaman, H.E.; de Vries, C.S.; Wright, J.T. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study—Part 1. BJOG 2008, 115, 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafrir, A.L.; Farland, L.V.; Shah, D.K.; Harris, H.R.; Kvaskoff, M.; Zondervan, K.; Missmer, S.A. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, A.; Gilmour, J.A. A life shaped by pain: Women and endometriosis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005, 14, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Kennedy, S.; Barnard, A.; Wong, J.; Jenkinson, C. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument: The Endometriosis Health Profile-30. Obstet Gynecol. 2001, 98, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Burgt, T.J.; Hendriks, J.C.; Kluivers, K.B. Quality of life in endometriosis: Evaluation of the Dutch-version Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30). Fertil Steril. 2011, 95, 1863–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.L.; Budds, K.; Taylor, F.; Musson, D.; Raymer, J.; Churchman, D.; Kennedy, S.H.; Jenkinson, C. A systematic review to determine use of the Endometriosis Health Profiles to measure quality of life outcomes in women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2024, 30, 186–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S. Evaluating the responsiveness of the Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire: The EHP-30. Q. Life Res. 2004, 13, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Jenkinson, C.; Taylor, N.; Mills, A.; Kennedy, S. Measuring quality of life in women with endometriosis: Tests of data quality, score reliability, response rate and scaling assumptions of the Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, K.; Kennedy, S.; Stratton, P. Pain scoring in endometriosis: Entry criteria and outcome measures for clinical trials. Report from the Art and Science of Endometriosis meeting. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckstein, J.; Saridogan, E.; Ulrich, U.A.; Sillem, M.; Oppelt, P.; Schweppe, K.W.; Krentel, H.; Janschek, E.; Exacoustos, C.; Malzoni, M.; et al. The #Enzian classification: A comprehensive non-invasive and surgical description system for endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; McCulloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of Digital Visual Analog Scale Pain Scoring with a Traditional Paper-based Visual Analog Scale in Adults. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2018, 2, e088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Kalfas, M.; Chisari, C.; Windgassen, S. Psychosocial factors associated with pain and health-related quality of life in Endometriosis: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain. 2022, 26, 1827–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppernick, F.; Zeppernick, M.; Janschek, E.; Wölfler, M.; Bornemann, S.; Holtmann, L.; Oehmke, F.; Brandes, I.; Scheible, C.M.; Salehin, D. QS ENDO Real—A Study by the German Endometriosis Research Foundation (SEF) on the Reality of Care for Patients with Endometriosis in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020, 80, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, J.A.; Hawe, J.; Clayton, R.D.; Garry, R. The effects and effectiveness of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: A prospective study with 2–5 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2003, 18, 1922–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, E.; Mustard, C.; Cohen, M.; Kung, R. Endometriosis: What is the risk of hospital admission, readmission, and major surgical intervention? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2005, 12, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakiba, K.; Bena, J.F.; McGill, K.M.; Minger, J.; Falcone, T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: A 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 111, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knabben, L.; Imboden, S.; Fellmann, B.; Nirgianakis, K.; Kuhn, A.; Mueller, M.D. Urinary tract endometriosis in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: Prevalence, symptoms, management, and proposal for a new clinical classification. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, B.; Nassif, J.; Trompoukis, P.; Barata, S.; Wattiez, A. Prevalence and management of urinary tract endometriosis: A clinical case series. Urology 2011, 78, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccagnano, C.; Pellucchi, F.; Rocchini, L.; Ghezzi, M.; Scattoni, V.; Montorsi, F.; Rigatti, P.; Colombo, R. Ureteral endometriosis: Proposal for a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm with a review of the literature. Urol. Int. 2013, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulun, S.E.; Yilmaz, B.D.; Sison, C.; Miyazaki, K.; Bernardi, L.; Liu, S.; Kohlmeier, A.; Yin, P.; Milad, M.; Wei, J. Endometriosis. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1048–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, Z.; Simbar, M.; Hajian, S.; Zayeri, F.; Shahidi, M.; Saei Ghare Naz, M.; Ghasemi, V. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in infertile women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2020, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, Z.; Simbar, M.; Hajian, S.; Zayeri, F. The prevalence of depression symptoms among infertile women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ruan, X.; Lu, D.; Sheng, J.; Mueck, A.O. Effect of laparoscopic endometrioma cystectomy on anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, B.; Turkgeldi, E.; Seyhan, A.; Urman, B. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.P.W.; Law, T.S.M.; Mak, J.S.M.; Sahota, D.S.; Li, T.C. Ovarian reserve and recurrence 1 year post-operatively after using haemostatic sealant and bipolar diathermy for haemostasis during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 43, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drechsel-Grau, A.; Grube, M.; Neis, F.; Schoenfisch, B.; Kommoss, S.; Rall, K.; Brucker, S.Y.; Kraemer, B.; Andress, J. Long-Term Follow-Up Regarding Pain Relief, Fertility, and Re-Operation after Surgery for Deep Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindos, N.B.; Fulcher, I.R.; Donnellan, N.M. Pain and Quality of Life after Laparoscopic Excision of Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1610–1617.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, J.; Sterrenburg, M.; Lane, S.; Maheshwari, A.; Li, T.C.; Cheong, Y. Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 592–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Bandini, V.; Buggio, L.; Berlanda, N.; Somigliana, E. Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 27.8 (8.79) |

| Pain severity (Visual analogue scale) | 7.25 (1.87) |

| Number of patients n (%) | |

| First diagnosis | 70 (40.0) |

| Previous therapy | 105 (60.0) |

| Current therapy | |

| None | 99 (56.6) |

| Endocrine therapy | 63 (36.0) |

| Analgesia | 13 (7.4) |

| Typical endometriosis symptoms | |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 169 (96.6) |

| Dyspareunia | 67 (38.3) |

| Dysuria | 18 (10.3) |

| Dyschezia | 33 (18.9) |

| Main complaints | |

| Pain | 167 (95.3) |

| Findings requiring clarification | 4 (2.3) |

| Follow-up | 9 (5.1) |

| Persistent endometriosis | 25 (14.3) |

| Recurrence | 23 (13.1) |

| Desire to have children | 34 (19.4) |

| Operations | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 78 (44.6) |

| Previous endometriosis surgery | 60 (34.3) |

| Previous histological confirmation of endometriosis | 58 (33.1) |

| Location of endometriosis diagnosis | |

| Peritoneal (#ENZIAN P) | 111 (63.4) |

| Ovary (#ENZIAN O) | 10 (5.7) |

| Deep infiltrating endometriosis (#ENZIAN A/B/C) | 20 (11.4) |

| Adenomyosis uteri (#ENZIAN FA) | 74 (42.3) |

| Planned procedure | |

| Surgical therapy | 62 (35.4) |

| Drug-based pain therapy/analgesia | 17 (9.7) |

| Reproductive medicine | 5 (2.9) |

| Endocrine therapy | 127 (72.6) |

| Multiple R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Estimates | p-Values | R2 = 0.40 |

| Visual analogue scale pain | 6.27 | <0.0001 | |

| Dysuria | 15.10 | <0.001 | |

| Pain | −11.55 | 0.133 | |

| Persistent endometriosis | 11.69 | <0.01 | |

| Desire to have children | −11.13 | <0.001 | |

| Previous endometritis surgery | −5.56 | 0.087 | |

| Control and powerlessness | R2 = 0.32 | ||

| Visual analogue scale pain | 5.63 | <0.0001 | |

| Dysmenorrhoea | −13.47 | 0.151 | |

| Dysuria | 16.07 | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up | 17.51 | <0.05 | |

| Persistent endometriosis | 15.40 | <0.01 | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 8.63 | 0.079 | |

| Previous endometriosis surgery | −8.03 | 0.152 | |

| Peritoneal endometriosis | 7.91 | <0.05 | |

| Adenomyosis uteri | 5.24 | <0.01 | |

| Emotional well-being | R2 = 0.18 | ||

| Age | −0.38 | <0.05 | |

| Visual analogue scale pain | 3.00 | <0.01 | |

| Dysuria | 10.48 | <0.05 | |

| Pain | −14.60 | 0.095 | |

| Findings requiring clarification | 14.28 | 0.147 | |

| Recurrence | −7.41 | 0.150 | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 14.16 | <0.01 | |

| Previous endometriosis surgery | −9.43 | 0.084 | |

| Ovary | 16.09 | <0.05 | |

| Reproductive medicine | 12.62 | 0.141 | |

| Social support | R2 = 0.14 | ||

| Dysuria | 14.57 | <0.05 | |

| Persistent endometriosis | 8.04 | 0.129 | |

| Recurrence | −14.21 | <0.05 | |

| Ovary | 19.03 | <0.05 | |

| Surgical therapy | 15.92 | <0.001 | |

| Endocrine therapy | 9.84 | 0.053 | |

| Self-image | R2 = 0.052 | ||

| First diagnosis | −6.89 | 0.156 | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 18.90 | <0.01 | |

| Previous endometriosis surgery | −18.89 | <0.05 |

| MAE (Mean Absolute Error)/Leave One Out | RMSE (Root Mean Square Error)/Leave One Out | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metrics Multivariate Linear Regression | Performance Metrics Random Forest | Performance Metrics Multivariate Linear Regression | Performance Metrics Random Forest | |

| Pain | 13.68 | 14.25 | 16.80 | 17.70 |

| Control and Powerlessness | 15.65 | 16.55 | 19.54 | 20.51 |

| Emotional well-being | 15.07 | 15.79 | 19.04 | 19.90 |

| Social support | 19.42 | 19.77 | 24.28 | 24.75 |

| Self-image | 22.39 | 22.40 | 26.05 | 26.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kupec, T.; Kennes, L.N.; Senger, R.; Meyer-Wilmes, P.; Najjari, L.; Stickeler, E.; Wittenborn, J. The Multifactorial Burden of Endometriosis: Predictors of Quality of Life. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020323

Kupec T, Kennes LN, Senger R, Meyer-Wilmes P, Najjari L, Stickeler E, Wittenborn J. The Multifactorial Burden of Endometriosis: Predictors of Quality of Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020323

Chicago/Turabian StyleKupec, Tomas, Lieven Nils Kennes, Rebecca Senger, Philipp Meyer-Wilmes, Laila Najjari, Elmar Stickeler, and Julia Wittenborn. 2025. "The Multifactorial Burden of Endometriosis: Predictors of Quality of Life" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020323

APA StyleKupec, T., Kennes, L. N., Senger, R., Meyer-Wilmes, P., Najjari, L., Stickeler, E., & Wittenborn, J. (2025). The Multifactorial Burden of Endometriosis: Predictors of Quality of Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020323