1. Introduction

Clinical empathy is the physician’s ability to understand and communicate the patient’s perspective, with measurable effects on satisfaction, anxiety, and adherence. In pediatrics, parents’ perceptions strongly influence care experience. Beyond individual clinician skills, empathic perception is also shaped by systemic and organizational factors. Studies show that time pressure, outpatient volume, and institutional support for communication training can significantly influence how empathy is expressed and perceived in consultations [

1,

2]. Recent pediatric research further suggests that smoother empathic interactions are observed in clinical settings with lower workload and stronger structural continuity, such as pediatric rheumatology or general surgery, compared with high-pressure environments like psychiatry or emergency care [

3,

4]. This broader view underscores that empathy is not only an individual trait but also an emergent property of the healthcare context.

In pediatrics, the communication pathway is often mediated by the caregiver (parent/guardian), and their expectations and perceptions can directly influence satisfaction, understanding of recommendations, and information retention after the consultation. Studies from pediatric services show that perceived empathy by caregivers is a major determinant of satisfaction—more significant even than demographic characteristics of the family or the physician—highlighting empathy’s role as a central link in the quality of the clinical relationship in child care [

5,

6,

7]. Prior research has shown that caregiver expectations and perceptions influence satisfaction, adherence, and cooperation in pediatric and child psychiatry [

7,

8,

9].

A large cross-sectional study in Israel revealed that over 55% of parents are concerned about psychosocial issues. However, fewer than half actually discussed these concerns with pediatricians, and nearly 60% believe such issues fall outside the pediatrician’s role. This emphasizes how parental expectations can affect the level of empathetic engagement and conversations about mental health.

Pediatric care increasingly requires multidisciplinary approaches that integrate not only biomedical but also psychological and communicative dimensions.

Empathy is highly relevant in pediatric psychiatry, where anxiety, avoidant behaviors, communication difficulties, and the need for predictability can amplify the vulnerability of both the child and their family. Differences between children with and without autism spectrum disorders indicate that communication should be explicitly adapted to neurodevelopmental particularities to ensure a positive experience. Recent data suggest that in neurodevelopmental care, children tend to evaluate their relationship with the physician more critically than parents or clinicians do, reinforcing the need for visible empathic behaviors directed specifically at the child [

10,

11,

12].

In interpreting ASD-related differences, we adopt the

double empathy problem perspective: communication breakdowns can be bidirectional, arising from mismatches in communicative style, sensory processing, and expectations between autistic individuals/families and clinicians, rather than reflecting clinician shortcomings alone. This framework helps explain why parent-reported empathy may be lower in ASD when usual routines are not adapted (e.g., predictable sequencing, concrete language, additional processing time, reduced sensory load) and shifts the focus toward mutual accommodation and context-sensitive adaptations that make empathic intent visible to the child and family [

13,

14]. As a converging example from pediatrics, caregiver-perceived empathy in orthopedic clinics was strongly associated with feeling carefully listened to (

p < 0.001) and respected (

p = 0.007), underscoring the centrality of attentive listening in empathic perception [

6].

Within the Transactional Model of Physician Compassion, a systematic review identified numerous factors that influence empathy and compassion, offering a conceptual framework that can inform the interpretation of predictors in our regression analyses [

15].

In this context, measuring the physician’s clinical empathy through the parent’s perspective provides a practical insight into the quality of the doctor-child relationship. It highlights areas where empathetic behaviors can be improved. Basing this approach on validated frameworks (such as operational definitions and established instruments) and linking it to outcomes meaningful to the family (like satisfaction, anxiety, and the child’s condition at the end of the consultation) can lay a strong foundation for educational initiatives and organizational enhancements in pediatric psychiatry. The Transactional Model of Physician Compassion highlights how intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual factors shape empathic behaviors in clinical encounters [

9,

16].

Although clinical empathy has been widely examined in pediatrics and validated, quantitative assessments specific to pediatric psychiatry remain scarce. Much of the available work addresses broader caregiver–clinician communication or non-psychiatric contexts (e.g., surgical/orthopedic clinics) where empathy has been measured with established tools, but not within routine child and adolescent mental-health consultations. Moreover, when empathy is assessed via parent-proxy alone, scores may diverge from those reported by children or clinicians due to differences in perspective, health literacy, and social-desirability/halo effects. These gaps underscore the need for psychiatry-specific validations and multi-informant approaches that triangulate parent, child, and clinician reports [

17,

18,

19]

While there are pediatric validations of patient-reported empathy tools (e.g., the Visual CARE Measure in pediatric emergency departments), parent-reported proxy applications in child psychiatry remain rare and fragmented; many studies focus on satisfaction or communication strategies rather than empathy operationalized and measured in a standardized way during mental health consultations [

7,

17].

Recent methodological reviews highlight the heterogeneity in measuring empathy (tools, perspectives, outcomes), which complicates extrapolation to CAMHS; in parallel, pediatric literature documents high-emotional-load situations (e.g., intensive care conferences) where physicians’ empathic responses are analyzed, but again outside the framework of outpatient pediatric psychiatry [

7,

20].

Ultimately, professional guidance clearly supports empathetic communication as a key skill in pediatric mental health practice, but it still lacks a strong base of quantitative studies focused on parents’ perceptions during current (everyday) consultations. This gap between recommendations and direct quantitative evidence motivates the present analysis.

Despite substantial evidence on empathy in pediatrics, few studies focus specifically on outpatient child psychiatry. Parental perceptions provide a unique proxy for the quality of physician–child interaction in this vulnerable population, justifying the present analysis.

Beyond individual clinician–child exchanges, perceptions of empathy are also shaped by psychosocial, cultural, and organizational contexts. Caregiver expectations, health literacy, and culturally grounded communication norms can modulate how the same behaviors are interpreted, while service-level factors (e.g., clinic workflow, time constraints, continuity of care) influence opportunities to display empathic behaviors. In neurodevelopmental care, the “double empathy problem” highlights that communication breakdowns may be bidirectional—arising from misaligned communicative styles between clinicians and autistic individuals—rather than solely from clinician shortcomings. These perspectives are particularly salient in child and adolescent mental health, where anxiety, sensory load, and the need for predictability intersect with family stress and sociocultural values. Accordingly, we interpret parent-reported empathy within this wider ecological frame and examine how observable behaviors (clear explanations, direct child address, active listening) relate to family-relevant experience indicators [

13,

17,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

1.2. Secondary Objectives

- 2.

To identify differences between subgroups in terms of perceived empathy, by comparing the total score between:

diagnostic categories (clinically aggregated groups),

parent/relative gender,

parent educational level,

residential environment (urban vs. rural).

- 3.

To estimate correlations between perceived empathy and:

child age (years, continuous variable),

child condition at the end of the consultation (ordinal scale: “understood and calm” ↔ “still scared”).

- 4.

Identifying independent predictors of perceived empathy (total score) through regression models (e.g., OLS), having as potential predictors: diagnosis, child age, parent gender, educational level, and residential environment.

- 5.

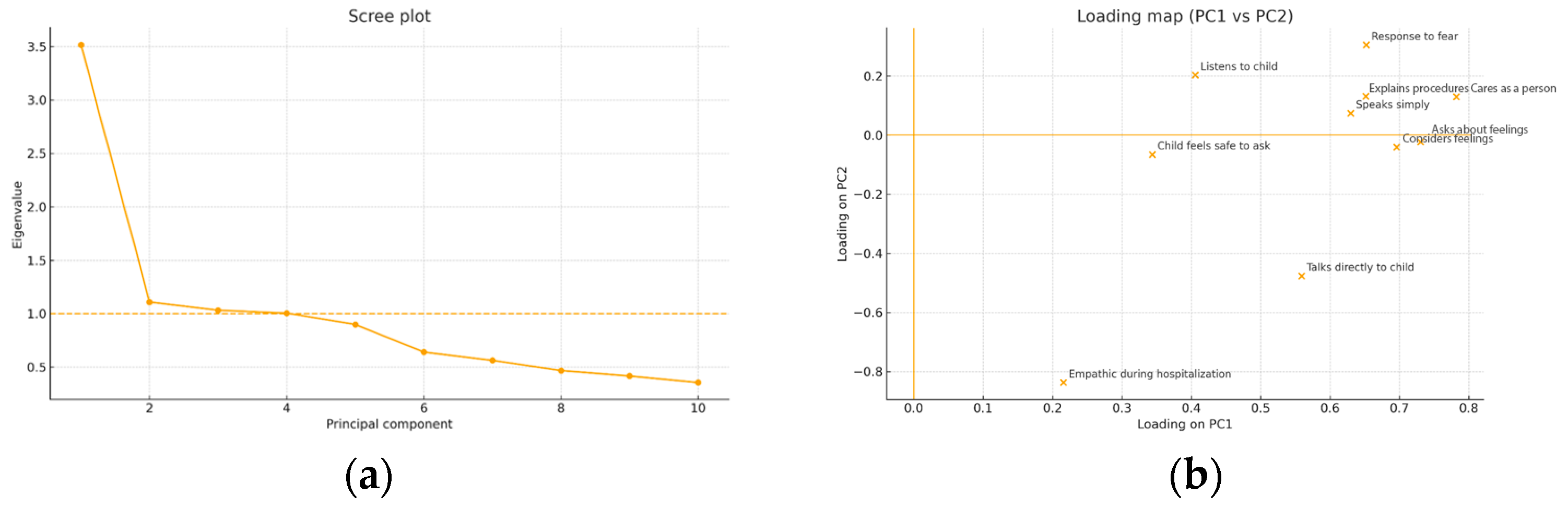

Exploring the dimensionality of the empathy scale (exploratory factor analysis/PCA) to assess the existence of a general factor and/or specific dimensions (e.g., explanation, active listening, direct addressing of the child), as well as estimating the internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) of the instrument.

4. Discussion

Our findings should be interpreted within the specific context of outpatient child and adolescent psychiatry. Where caregiver mediation is pervasive and symptom profiles (e.g., avoidance, cognitive rigidity, heightened arousal) render empathic behaviors not merely desirable but integral to therapeutic engagement. Compared with general pediatrics, these consultations more often involve elevated anxiety, communication differences, and a need for predictable, low-stimulus interactions—features that shape both the enactment and the perception of empathy, especially when communication is filtered through caregivers. In this setting, higher parent-perceived empathy was associated with a calmer, more understood end-of-visit state for the child, a pattern consistent with prior work linking expressed clinician empathy to patient satisfaction and perceived care quality, including evidence from randomized trials and meta-analytic syntheses supporting empathy-enhancement interventions [

26]. Brief pre-consultation compassion prompts have likewise been shown to reduce patient anxiety, offering a plausible mechanism for the observed association [

26,

27,

28,

29].

The link between empathy and a calmer departure state should be viewed as correlational, not causal. Reverse causality is plausible—children who leave the visit calmer may lead parents to perceive greater empathy from the clinician. While the directionality aligns with evidence that empathic communication attenuates anxiety, our cross-sectional design precludes inference about temporal or causal pathways.

Evidence from pediatric intensive care conferences indicates that when physicians deliver unburied empathetic statements and then pause, families are dramatically more likely to share emotional concerns (OR 18; 95% CI 10.1–32.4;

p < 0.001), underscoring that not just empathy—but the timing and delivery of it—is critical for fostering parent-clinician connection [

30].

Recent research among pediatricians revealed that high outpatient volume and communication constraints can negatively affect empathy expression; conversely, smoother interactions were observed in settings like rheumatology and general surgery, suggesting that clinical context and workload significantly modulate empathic behavior [

31].

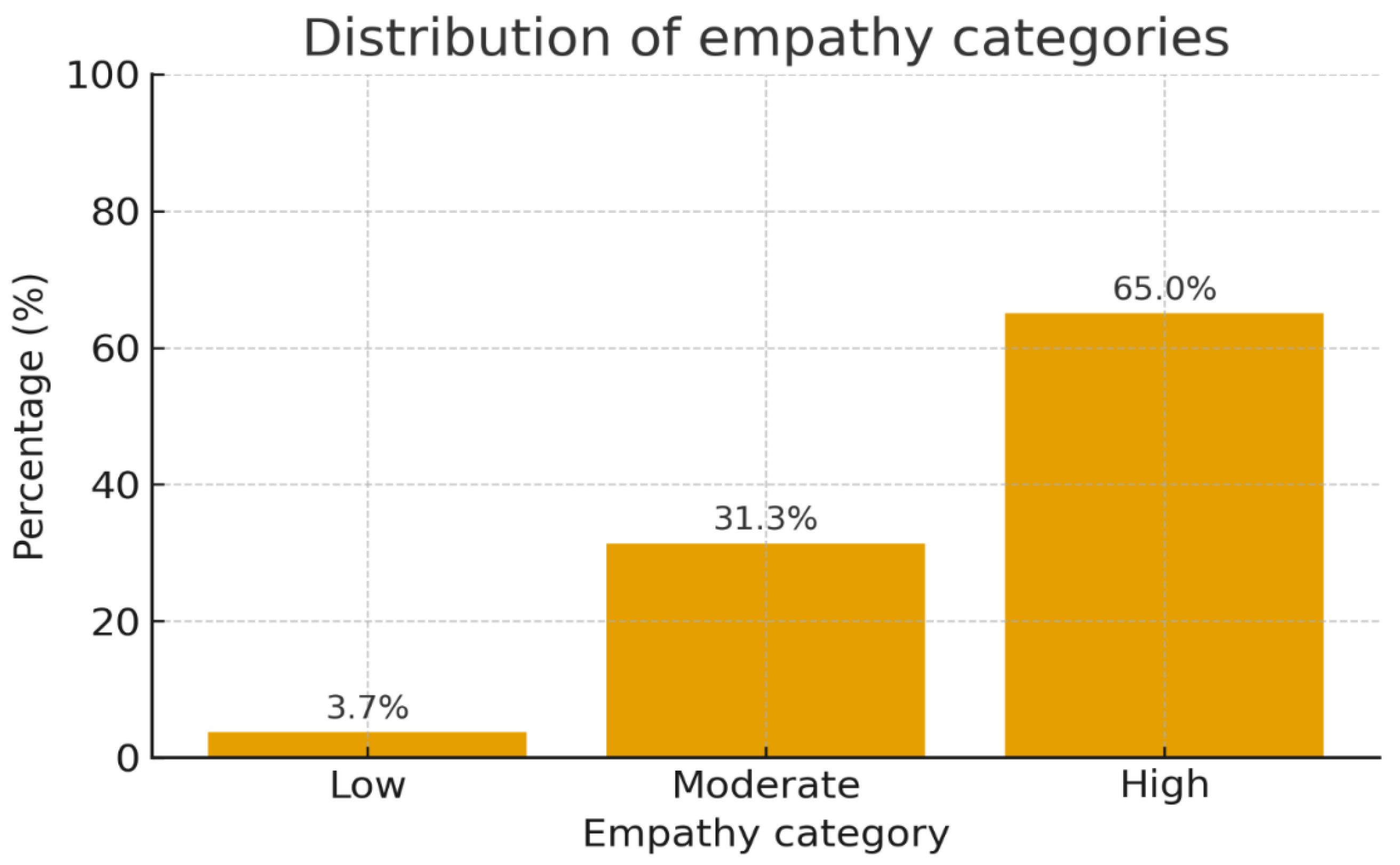

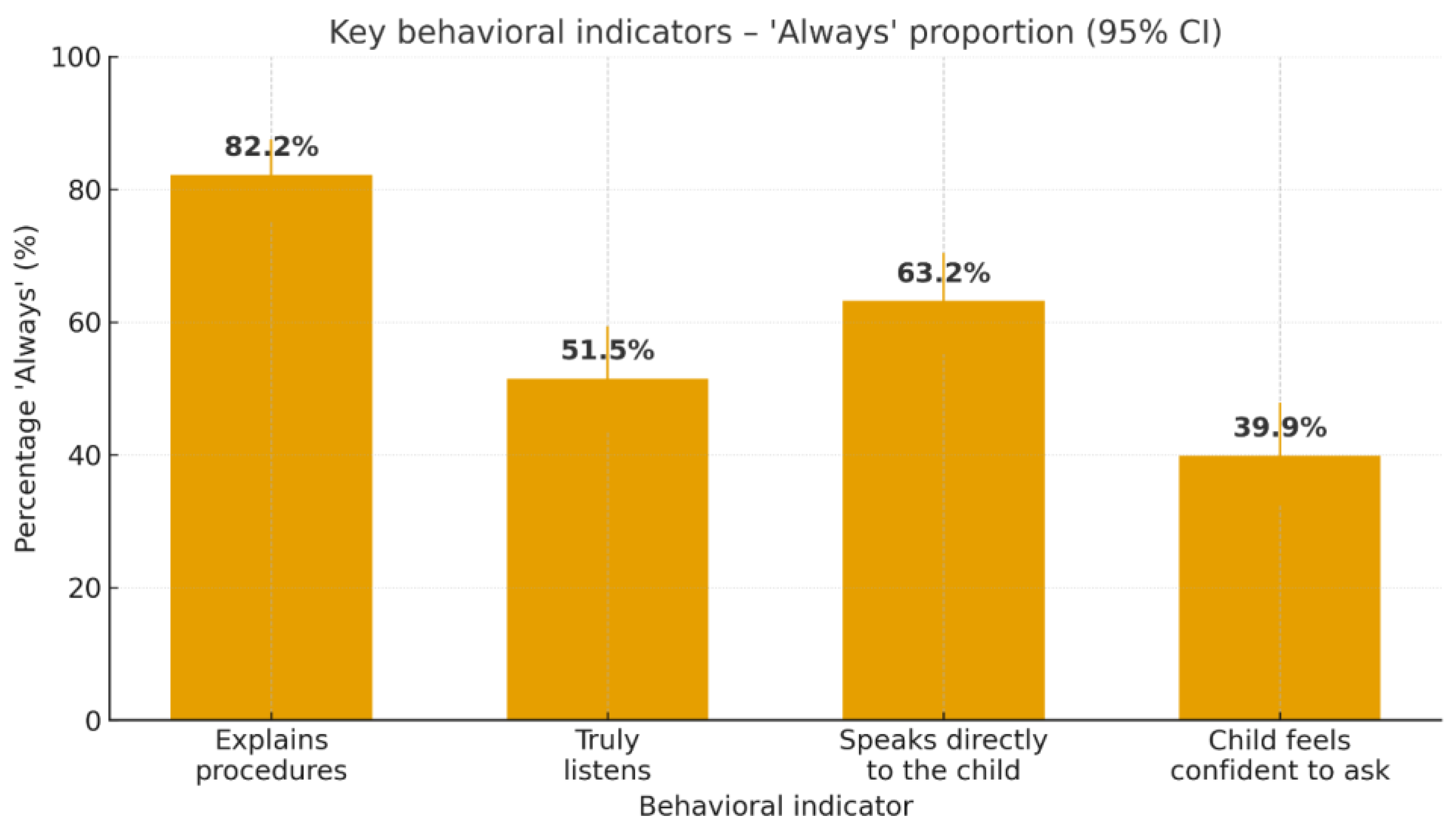

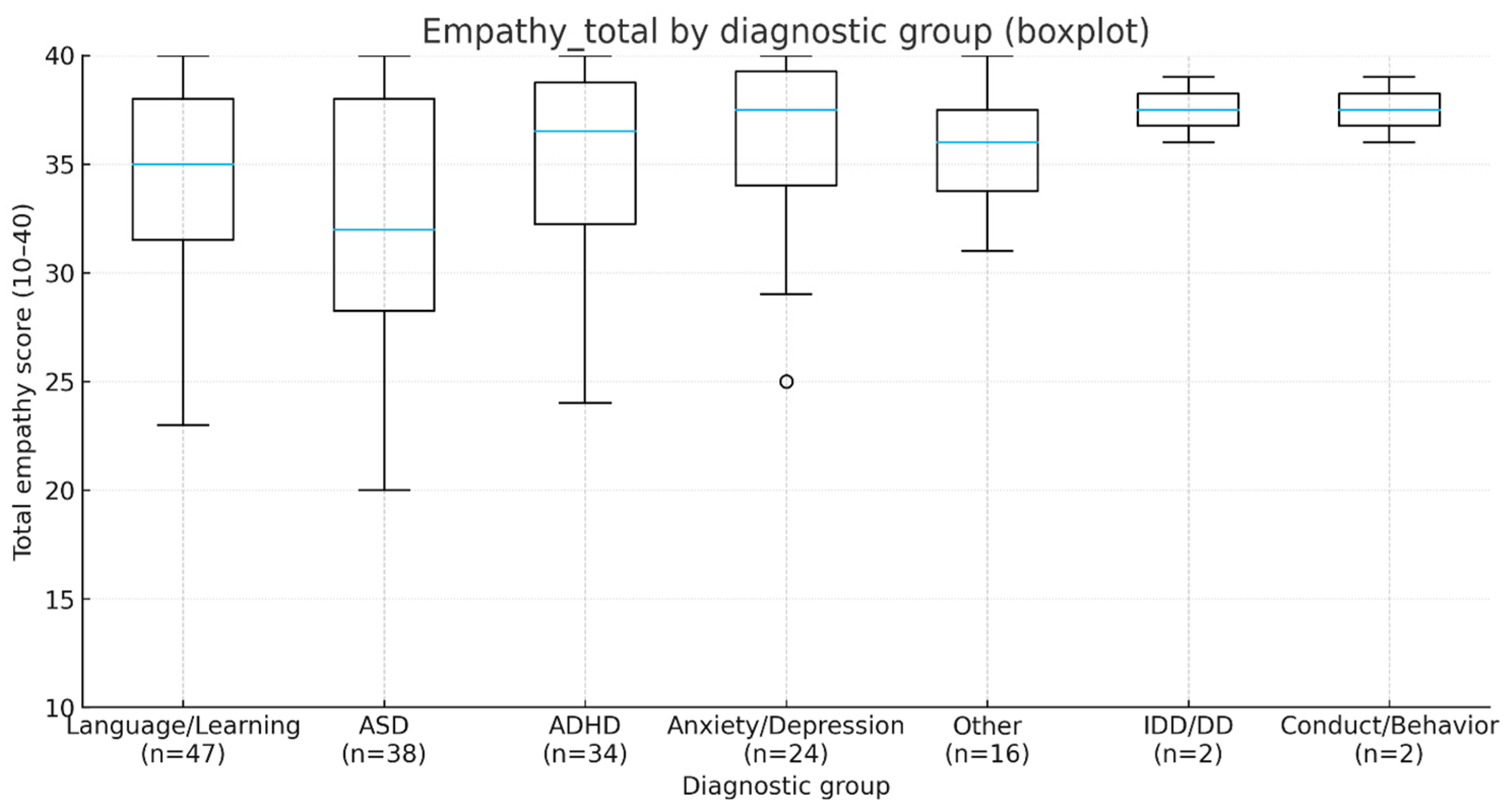

To ensure logical consistency, we revisit our objectives in the same order as introduced: (i) overall empathy levels, (ii) subgroup differences, (iii) correlational patterns, (iv) independent predictors, and (v) dimensionality of the empathy scale. First, we found high mean empathy scores, yet with evident gaps in active listening and in encouraging questions. Second, regarding subgroup differences, only the ASD vs. anxiety/depression contrast remained significant after correction, while all other differences should be considered tentative. Third, empathy correlated modestly with child age and moderately with the child’s end-of-visit calmness. Fourth, the regression explained approximately 10% of the variance, suggesting that relevant contextual variables were not captured. Finally, PCA indicated a general empathy factor and potential subdimensions, but with borderline adequacy and several items showing near-zero communalities.

The convergence between our findings and prior literature on observable communication behaviors is noteworthy. Studies in pediatric outpatient settings consistently highlight a set of strategies that positively shape families’ perception of communication quality: explaining the next steps, using simple language, actively soliciting questions, and addressing the child directly whenever possible. Data from pediatric intensive care consultations also demonstrate that “unburied” empathic statements—followed by a deliberate pause—facilitate therapeutic alliance and disclosure of family values and concerns. This procedural detail offers a plausible explanation for why active listening and encouraging questions emerged in our sample as weaker yet high-yield targets for improvement [

30,

32].

Our finding of lower empathy scores in children with ASD is consistent with contemporary literature emphasizing the need for specific adaptations in clinical interaction to reduce sensory load and increase predictability. Recommended strategies include flexible scheduling, stepwise explanations supported by visual aids, additional processing time, and the use of literal, direct language. Recent reviews underline those barriers related to the “double empathy problem” and atypical communicative demands may erode the perception of empathy in the absence of such adaptations, even when clinicians’ intentions are empathic. These observations provide context for the negative coefficient of the ASD diagnosis in our OLS model [

33,

34,

35]. Our findings of diagnosis-related differences in parent-perceived empathy, with lower scores particularly in children with ASD, resonate with broader psychiatric literature emphasizing the role of symptom severity and clinical complexity as predictors of patient–clinician interaction quality. Recent work in adult schizophrenia has highlighted that both predictive factors and the spectrum of symptom severity strongly influence care experiences and management needs, underscoring the importance of adapting physician communication to diagnostic profiles [

36].

While lower empathy ratings in ASD are consistent with previous literature, alternative explanations should be acknowledged. Parental expectations of additional accommodations, caregiver stress, and the child’s communicative profile (e.g., atypical reciprocity, sensory sensitivities) may all influence how empathic behaviors are perceived and rated. The “double empathy problem” framework further emphasizes that communication breakdowns can be bidirectional, arising not solely from physician shortcomings but also from mismatched styles and expectations between autistic children and clinicians.

The clinical implications are immediate:

Standardizing empathic behaviors through structured checklists (e.g., Kalamazoo/KEECC, m-SPIKES) and micro-behavioral steps (explain–listen–summarize–pause) appears both rational and feasible. Educational interventions for residents and students have demonstrated measurable gains in communication and empathy skills, including in randomized trials [

37,

38,

39].

For neurodivergent populations, “autism-friendly” protocols advocate environmental and communicative adaptations co-designed with service users; their implementation increases trust and reduces distress [

33,

35].

Incorporating parent–child feedback into quality assessment via PREMs aligns with recent pediatric service recommendations, where patient- and family-reported measures are increasingly used as indicators of care quality [

33,

35,

37,

38,

39,

40].

At the educational and systems level, there is growing support for integrating structured training in clinical empathy and family communication into medical curricula. Recent reviews and meta-analyses show that empathy can be taught and maintained through active methods such as role-play, video-feedback, empathy portfolios, and deliberate practice. From a quality-management perspective, routine use of PROMs and PREMs in pediatrics has been associated with improvements in communication, shared decision-making, identification of unmet needs, and monitoring of intervention outcomes [

1,

37,

41,

42].

The strengths of our study include completeness of scale data, good internal consistency, and convergence of results across correlational analyses, OLS regression, and exploratory principal component analysis. Limitations relate to the single-center design and reliance on the parental (proxy) perspective, both well-discussed in pediatric PREM literature, where parent–child discrepancies may occur and warrant documentation. Future research should include children’s direct reports and triangulation with validated empathy-perception instruments (e.g., JSPE/JSPE-HP, JSPPPE, Visual CARE) [

13,

17,

18,

19]. We also did not measure consultation length, a potentially relevant variable for perceived empathy [

40,

43,

44,

45]. It is particularly important to stress that parent-only proxy data may diverge from children’s self-reported experiences; previous PREM research consistently documents discrepancies between informants, underscoring the necessity of multi-informant approaches.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single outpatient child psychiatry clinic in Romania, which restricts generalizability to other cultural or service contexts. Second, the findings are based exclusively on parental (proxy) reports, omitting the perspectives of children and clinicians; prior PREM research shown consistent discrepancies between informants, underscoring the need to triangulate multiple viewpoints. Third, we did not prospectively capture the denominator of approached/eligible families, precluding calculation of a participation rate and preventing a formal assessment of selection bias. Fourth, the range of psychiatric diagnoses represented was limited, with small subsamples in several groups, reducing statistical power. Fifth, the empathy scale demonstrated only moderate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.76) and borderline factorability, with some items contributing limited discriminative variance; accordingly, dimensional inferences remain exploratory. Finally, we did not measure potentially important contextual confounders (e.g., consultation length, clinician-level factors, prior therapeutic relationship), which may account for additional variance in perceived empathy. These issues caution against overinterpretation and highlight the need for replication in larger, multi-center samples using validated, multi-informant tools.

Future Directions Include

- 8.

pragmatic trials of brief educational interventions to standardize empathic behaviors, assessed through PREMs;

- 9.

integration of consultation duration and process indicators (e.g., the “pause after an empathic statement”);

- 10.

triangulation of parent–child–clinician perspectives using validated instruments; and

- 11.

evaluation of impact on child anxiety and family satisfaction [

26,

30].

5. Conclusions

Parent-perceived physician empathy was generally high in this outpatient pediatric psychiatry sample, with variation across diagnostic groups. Perceptions appear shaped not only by individual skills but also by contextual features of child mental-health care. Exploratory PCA provided tentative evidence of potential subdimensions—child-centered clarity/direct address and listening/facilitation—that warrant replication with larger samples and refined items. Clinically, visible empathic behaviors (active listening, stepwise explanations, direct engagement, facilitation of questions) should be prioritized. For autism, adaptations should also reflect the double empathy problem, emphasizing mutual accommodation (predictability, concrete language, additional processing time, reduced sensory load). Correlational and multivariable results indicated a modest association with child age and a link to a calmer, more understood end-of-visit state; these associations are non-causal and should be interpreted cautiously. Embedding structured training (e.g., checklists and micro-steps such as explain–listen–check understanding–encourage questions) and PREM-based feedback into routine practice may strengthen the therapeutic alliance and improve the care experience for children and families.

While empathy is globally perceived as good, its added value is realized through concrete behaviors and targeted adaptations, particularly for children with ASD. Training programs and systematic feedback can transform empathy from a declarative principle into an observable standard of care, with direct impact on the child’s emotional comfort and the family’s long-term collaboration.

Clinical Implications

The present findings underscore that empathy in pediatric psychiatry is not merely an attitudinal construct but a set of observable behaviors that can be standardized, trained, and monitored. Embedding structured empathic behaviors into daily clinical routines—such as explaining next steps clearly, directly addressing the child, checking understanding, and encouraging questions—has the potential to improve both child comfort and family trust. For children with autism spectrum disorder, the incorporation of neurodiversity-specific adaptations (predictable sequencing, concrete language, visual supports, and sensory-friendly environments) is particularly important to ensure equitable care experiences.

At the systems level, routine integration of PREMs (Patient Reported Experience Measures) offers a feasible and family-centered approach to monitoring empathic communication as a quality indicator. From an educational standpoint, brief, structured training modules and feedback loops for residents and early-career clinicians can help translate empathy from a declared principle into an observable standard of care, thereby strengthening therapeutic alliance and long-term collaboration with families.