Evaluating the Divide Between Patients’ and Physicians’ Perceptions of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease Cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.1.1. Time to Diagnosis

3.1.2. Disease Course

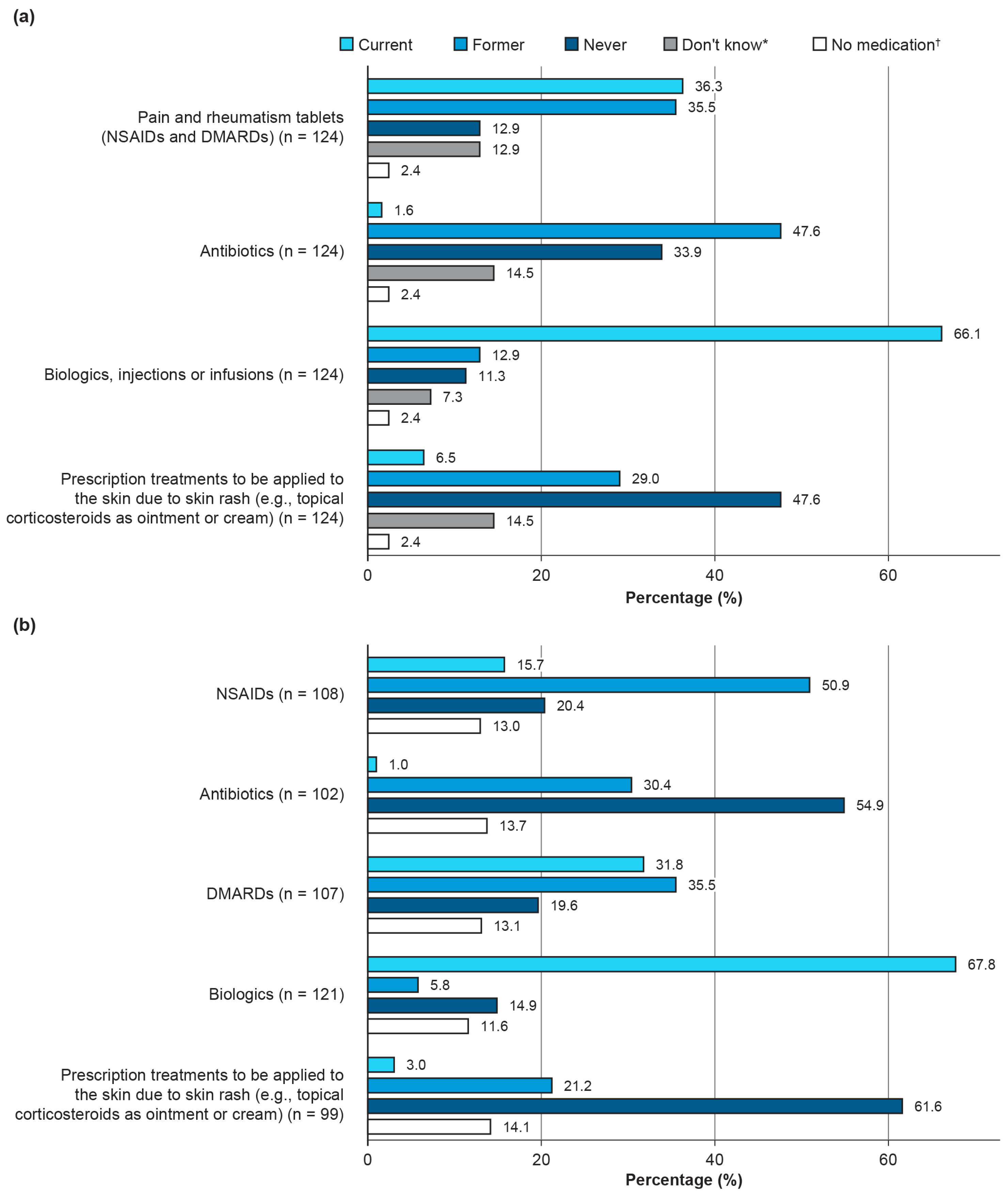

3.1.3. Current and Past Medication

3.2. Laboratory Findings

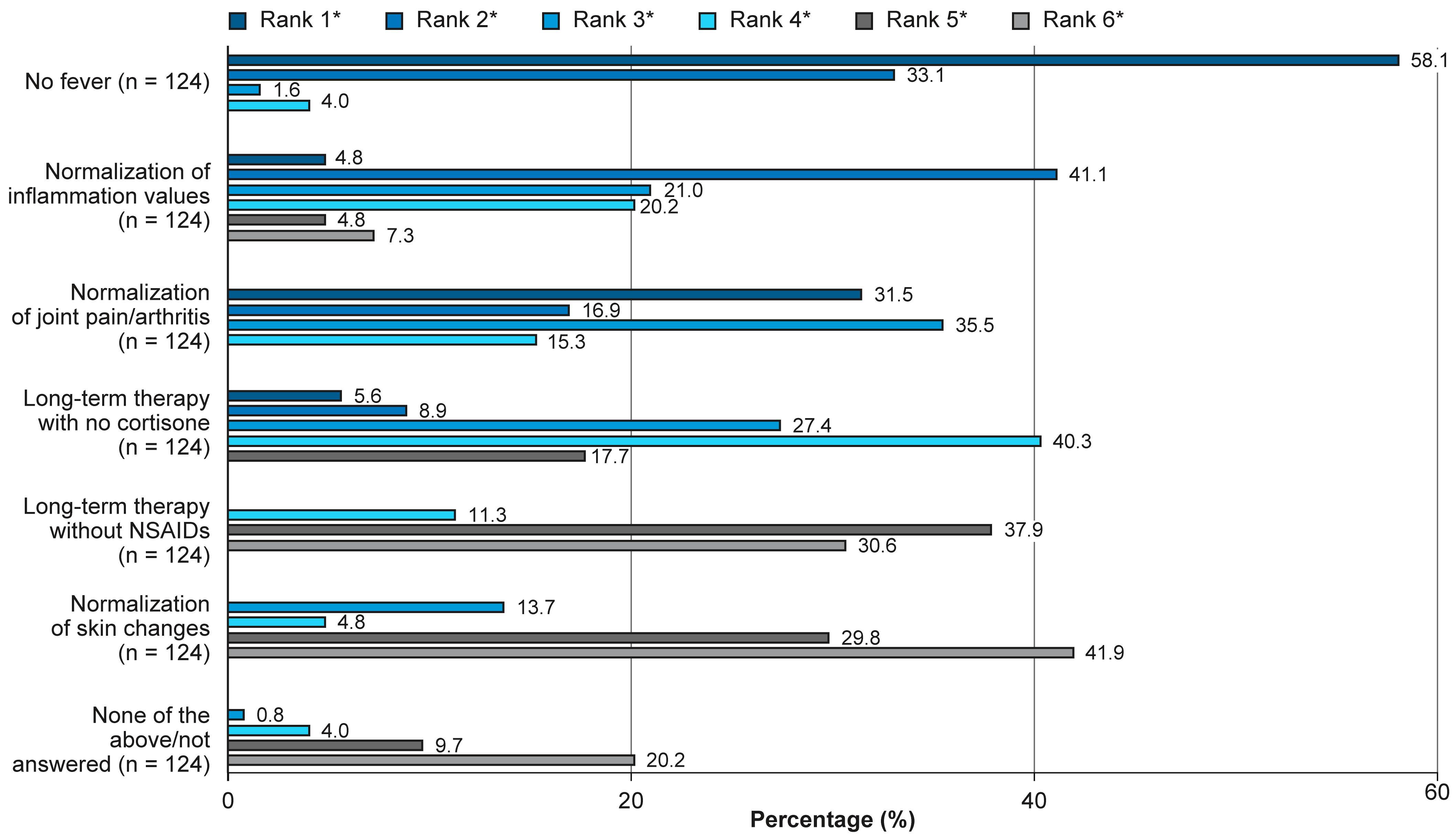

3.3. Physicians’ Treatment Goals

3.4. Physicians’ Assessments of Patients’ Health States

3.5. Pain, Disease Activity, and Symptoms

3.6. Disease Activity Determined by CRP Levels

3.7. Impact of External Factors on Disease Improvement

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AID | Autoimmune disease |

| AOSD | Adult-onset Still’s disease |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DAS28 | Disease Activity Score 28 |

| DMARD | Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| N/n | Number of patients |

| NSAID | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcome |

| PRO-AOSD | Patient-reported outcomes adult-onset Still’s disease |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 |

| sJIA | Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| WPAI | Work Productivity and Activity Impairment |

References

- De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; De Benedetti, F.; Carmona, L.; Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S. Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease are the same disease: Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses informing the 2023 EULAR/PReS recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Still’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S.; De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; Antón, J.; Belot, A.; Bracaglia, C.; Constantin, T.; Dagna, L.; Di Bartolo, A.; et al. EULAR/PReS recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Still’s disease, comprising systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seco, T.; Cerqueira, A.; Costa, A.; Fernandes, C.; Cotter, J. Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Typical Presentation, Delayed Diagnosis. Cureus 2020, 12, e8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthimiou, P.; Kontzias, A.; Hur, P.; Rodha, K.; Ramakrishna, G.S.; Nakasato, P. Adult-onset Still’s disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the era of targeted therapies. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vordenbaumen, S.; Feist, E.; Rech, J.; Fleck, M.; Blank, N.; Haas, J.P.; Kotter, I.; Krusche, M.; Chehab, G.; Hoyer, B.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease: A concise summary of the German society of rheumatology S2 guideline. Z. Rheumatol. 2023, 82, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomelli, R.; Caporali, R.; Ciccia, F.; Colafrancesco, S.; Dagna, L.; Govoni, M.; Iannone, F.; Leccese, P.; Montecucco, C.; Pappagallo, G.; et al. Expert consensus on the treatment of patients with adult-onset still’s disease with the goal of achieving an early and long-term remission. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, E.; Mitrovic, S.; Fautrel, B. Mechanisms, biomarkers and targets for adult-onset Still’s disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, S.; Fautrel, B. Clinical Phenotypes of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: New Insights from Pathophysiology and Literature Findings. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Patterson, J.; Bowe, C.; Arber, M.; Glanville, J.; Mealing, S.; Canon-Garcia, V.; Fagerhed, L.; Rabijns, H.; Giacomelli, R. Systematic review on the use of biologics in adult-onset still’s disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2023, 58, 152139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Caggiano, V.; Maggio, M.C.; Lopalco, G.; Emmi, G.; Sota, J.; La Torre, F.; Ruscitti, P.; Bartoloni, E.; Conti, G.; et al. Canakinumab as first-line biological therapy in Still’s disease and differences between the systemic and the chronic-articular courses: Real-life experience from the international AIDA registry. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1071732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Mitrovic, S.; De Matteis, A.; Bindoli, S.; Anton, J.; Belot, A.; Bracaglia, C.; Constantin, T.; Dagna, L.; de Bartolo, A.; et al. EULAR/PreS Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (sJIA) and Adult Onset Still’s Disease (AOSD) [abstract 0761]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.H.; Strand, V.; Oh, Y.J.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, E.B. Health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis compared with other rheumatic diseases: A cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Di Carlo, M.; Carotti, M.; Farah, S.; Ciapetti, A.; Gutierrez, M. The impact of different rheumatic diseases on health-related quality of life: A comparison with a selected sample of healthy individuals using SF-36 questionnaire, EQ-5D and SF-6D utility values. Acta Biomed. 2019, 89, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, P.; Rozza, G.; Di Muzio, C.; Biaggi, A.; Iacono, D.; Pantano, I.; Iagnocco, A.; Giacomelli, R.; Cipriani, P.; Ciccia, F. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with adult onset Still disease: Results from a multicentre cross-sectional study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumen, M.; De Cock, D.; Pazmino, S.; Bertrand, D.; Joly, J.; Westhovens, R.; Verschueren, P. Treatment response and several patient-reported outcomes are early determinants of future self-efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Alten, R.; Kirkham, B.; de la Torre, I.; Durand, F.; Barry, J.; Holzkaemper, T.; Fakhouri, W.; Taylor, P.C. Call for action: How to improve use of patient-reported outcomes to guide clinical decision making in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, V.; Schiff, M.; Tundia, N.; Friedman, A.; Meerwein, S.; Pangan, A.; Ganguli, A.; Fuldeore, M.; Song, Y.; Pope, J. Effects of upadacitinib on patient-reported outcomes: Results from SELECT-BEYOND, a phase 3 randomized trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuamanochan, M.; Weller, K.; Feist, E.; Kallinich, T.; Maurer, M.; Kummerle-Deschner, J.; Krause, K. State of care for patients with systemic autoinflammatory diseases—Results of a tertiary care survey. World Allergy Organ. J. 2019, 12, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, S.; Dagna, L.; Salvo, F.; Aiello, P.; Baldissera, E.; Sabbadini, M.G. Adult onset Still’s disease: Clinical presentation in a large cohort of Italian patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalyoncu, U.; Solmaz, D.; Emmungil, H.; Yazici, A.; Kasifoglu, T.; Kimyon, G.; Balkarli, A.; Bes, C.; Ozmen, M.; Alibaz-Oner, F.; et al. Response rate of initial conventional treatments, disease course, and related factors of patients with adult-onset Still’s disease: Data from a large multicenter cohort. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 69, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, S.; Tekgöz, E.; Mammadov, M.; Çınar, M.; Yılmaz, S. Biological treatment in resistant adult-onset Still’s disease: A single-center, retrospective cohort study. Arch. Rheumatol. 2022, 37, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardeo, M.; Rossi, M.N.; Pires Marafon, D.; Sacco, E.; Bracaglia, C.; Passarelli, C.; Caiello, I.; Marucci, G.; Insalaco, A.; Perrone, C.; et al. Early Treatment and IL1RN Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Affect Response to Anakinra in Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owlia, M.B.; Mehrpoor, G. Adult-onset Still’s disease: A review. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2009, 63, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, D.; Smirne, C.; Bruggi, F.; Bottino Sbaratta, C.; Tamen Njata, A.C.; Valente, G.; Pavanelli, M.C.; Vitetta, R.; Bellan, M.; De Paoli, L.; et al. Unveiling the Mystery of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: A Compelling Case Report. Life 2024, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, J.A.; Dilla, T.; Díaz-Cerezo, S.; Gabás-Rivera, C.; Aceituno, S.; Lizán, L. Patient-physician discrepancy in the perception of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. A qualitative systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez, J.; Mora-Liminana, M.; Ros, I.; Ibanez, M.; Valldeperas, J.; Cremer, D.; Nolla, J.M.; Juan-Mas, A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in adult-onset Still’s disease: A case series and systematic review of the literature. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2019, 49, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, R.E.; Yimer, B.B.; Roads, P.; Jani, M.; Dixon, W.G. Glucocorticoid use is associated with an increased risk of hypertension. Rheumatology 2020, 60, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.-Y.; Yao, Y.-M. The Clinical Significance and Potential Role of C-Reactive Protein in Chronic Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, C.; Sakurai, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Homma, R.; Huang, C.-L.; Fujita, M. mCRP as a Biomarker of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Quantification of mCRP by ELISA. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 938173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Benedetto, P.; Cipriani, P.; Iacono, D.; Pantano, I.; Caso, F.; Emmi, G.; Grembiale, R.D.; Cantatore, F.P.; Atzeni, F.; Perosa, F.; et al. Ferritin and C-reactive protein are predictive biomarkers of mortality and macrophage activation syndrome in adult onset Still’s disease. Analysis of the multicentre Gruppo Italiano di Ricerca in Reumatologia Clinica e Sperimentale (GIRRCS) cohort. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulutaş, F.; Senol, H.; Cobankara, V.; Karasu, U.; Kaymaz, S. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Adult-Onset Still Disease, their Relationship with Baseline Disease Activity and Subsequent Disease Course: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2021, 15, OC18–OC21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plebani, M. Why C-reactive protein is one of the most requested tests in clinical laboratories? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2023, 61, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTora, L.M.; Toroser, D.; Sykes, A.; Vanderlinden, C.; Plunkett, F.J.; Lane, T.; Hanekamp, E.; Dormer, L.; DiBiasi, F.; Bridges, D.; et al. Good Publication Practice (GPP) Guidelines for Company-Sponsored Biomedical Research: 2022 Update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 124 (100%) | n = 50 (40.3%) | n = 74 (59.7%) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 45.5 (14.7) | 44.8 (13.6) | 46 (15.4) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 79.0 (19.1) | 89.4 (16.2) | 72.0 (17.7) |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 170.8 (9.9) | 179.3 (7.2) | 165.1 (6.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.8) | 27.8 (4.7) | 26.4 (6.3) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 18 (14.5) | 7 (14.0) | 11 (14.9) |

| Serum Ferritin (µg/L) | CRP (mg/L) | ESR (mm/h) | AST (IU/L) | ALT (IU/L) | Leukocyte Count (Gpt/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid, n (%) | 88 (71.0) | 107 (86.3) | 77 (62.1) | 87 (70.2) | 107 (86.3) | 89 (71.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 36 (29.0) | 17 (13.7) | 47(37.9) | 37 (29.8) | 17 (13.7) | 35 (28.2) |

| Median | 118.5 | 2.5 | 11.0 | 27.0 | 25.0 | 6.3 |

| Mean | 562.2 | 16.04 | 16.6 | 30.1 | 36.8 | 7.6 |

| SD | 1879.1 | 47.9 | 21.0 | 15.3 | 43.0 | 4.0 |

| Minimum | 5.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 |

| Maximum | 16,000.0 | 300.0 | 100.0 | 91.0 | 385.0 | 28.0 |

| Please Rate Whether You Have Noticed Any Influence of the Following Factors on Your Symptoms (N = 124) | Positive Influence, Noticeably Improves My Disease Symptoms, n, (%) | Negative Influence, Worsens Disease Symptoms, n, (%) | No Influence or Does Not Apply, n, (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| More exercise or sport | 65 (52.4) | 18 (14.5) | 41 (33.1) |

| Fruit/vegetables | 39 (31.5) | 1 (0.8) | 84 (67.7) |

| Mediterranean diet | 32 (25.8) | 0 (0.0) | 92 (74.2) |

| Vegetarian/vegan diet | 25 (20.2) | 2 (1.6) | 97 (78.2) |

| Coffee/tea | 13 (10.5) | 6 (4.8) | 105 (84.7) |

| Smoke less | 10 (8.1) | 3 (2.4) | 111 (89.5) |

| Physical exertion | 8 (6.5) | 70 (56.5) | 46 (37.1) |

| Fruit juices | 7 (5.6) | 10 (8.1) | 107 (86.3) |

| Stress | 4 (3.2) | 92 (74.2) | 28 (22.6) |

| Infections (e.g., colds) | 3 (2.4) | 64 (51.6) | 57 (46.0) |

| Seasonal cold | 3 (2.4) | 68 (54.8) | 53 (42.7) |

| Sleep deprivation | 1 (0.8) | 78 (62.9) | 45 (36.3) |

| Increased meat consumption (e.g., daily sausage and meat) | 1 (0.8) | 30 (24.2) | 93 (75.0) |

| Fast food/finished products | 1 (0.8) | 29 (23.4) | 94 (75.8) |

| Sugary drinks (lemonade/cola) | 1 (0.8) | 22 (17.7) | 101 (81.5) |

| Alcohol consumption | 0 (0.0) | 31 (25.0) | 93 (75.0) |

| Hormonal fluctuations/monthly cycle | 0 (0.0) | 23 (18.5) | 101 (81.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blank, N.; Andreica, I.; Rech, J.; Sözen, Z.; Feist, E. Evaluating the Divide Between Patients’ and Physicians’ Perceptions of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease Cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7034. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197034

Blank N, Andreica I, Rech J, Sözen Z, Feist E. Evaluating the Divide Between Patients’ and Physicians’ Perceptions of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease Cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):7034. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197034

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlank, Norbert, Ioana Andreica, Jürgen Rech, Zekayi Sözen, and Eugen Feist. 2025. "Evaluating the Divide Between Patients’ and Physicians’ Perceptions of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease Cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD Survey" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 7034. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197034

APA StyleBlank, N., Andreica, I., Rech, J., Sözen, Z., & Feist, E. (2025). Evaluating the Divide Between Patients’ and Physicians’ Perceptions of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease Cases: Insights from the PRO-AOSD Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 7034. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197034