The Silent Cognitive Burden of Chronic Pain: Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Living Dose–Response Bayesian Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Primary Studies

2.1.2. Participants

2.1.3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

2.2. Systematic Search Strategy

2.3. Data Records and Screening Process

Benchmarking and Quality Assurance

2.4. Data Extraction

Effect Measures

2.5. Risk of Bias and Evidence Certainty Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

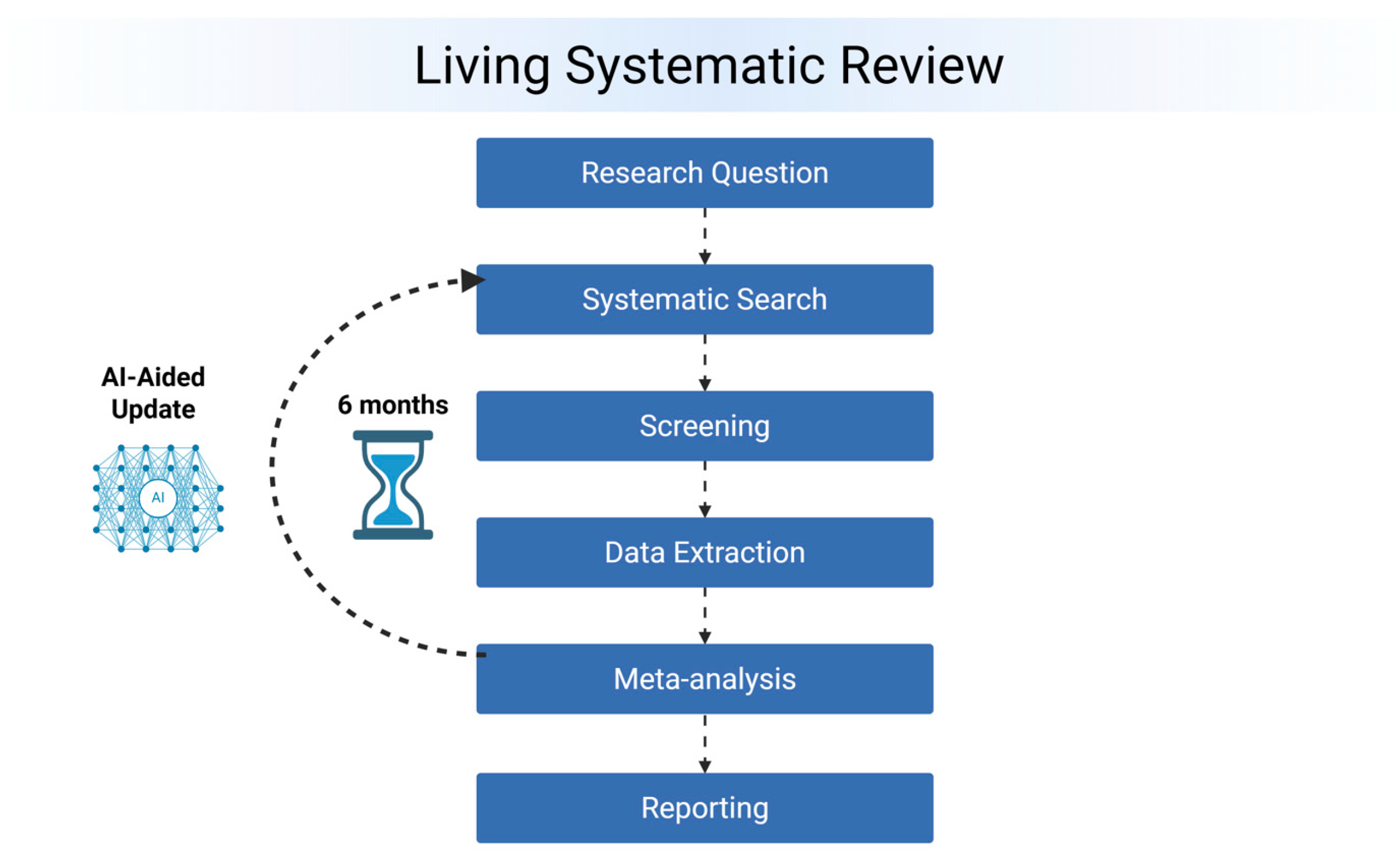

2.7. Living Update Process

3. Discussion

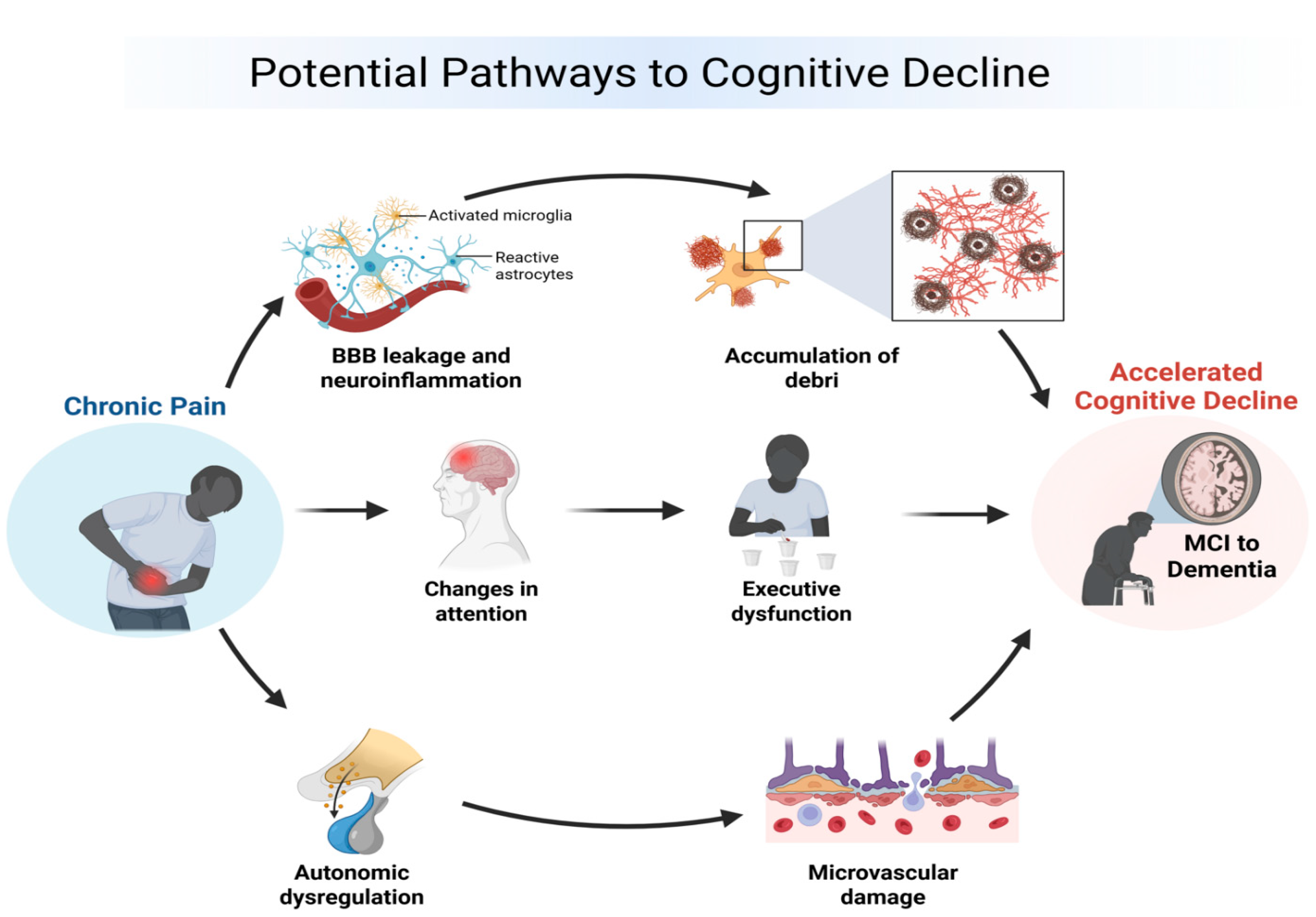

3.1. Potential Causal Pathways

3.2. New Approaches in Evidence Synthesis

3.3. Strengths and Limitations

3.4. Potential Impact

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.S.C.; Smith, B.H.; Blyth, F.M. Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain 2016, 157, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; Van Wilgen, P.; Kregel, J.; De Pauw, R.; Dolphens, M.; Ickmans, K. Brain changes associated with cognitive and emotional factors in chronic pain: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, V.A.; Hashmi, J.A.; Baliki, M.N. Pain and the brain: Specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 2011, 152, S49–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucyi, A.; Davis, K.D. The dynamic pain connectome. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z. The Relationship Between Chronic Pain and Cognitive Impairment in the Elderly: A Review of Current Evidence. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 2309–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, E.L.; Diaz-Ramirez, L.G.; Glymour, M.M.; Boscardin, W.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Smith, A.K. Association Between Persistent Pain and Memory Decline and Dementia in a Longitudinal Cohort of Elders. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Kim, Y.; Yu, F.; Heffner, K.L.; Quiñones-Cordero, M.M.; Li, Y. Pain and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Spectrum in Community-Dwelling Older Americans: A Nationally Representative Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, H. Association between chronic pain and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Ageing 2024, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Hsu, C.L.; Chung, R.; Wu, W.; Zheng, D.K.Y.; Xiong, Z.; Chang, J.R.; Zheng, Y.; et al. The Longitudinal Association Between Chronic Back Pain and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults With Mediation Analysis: An Analysis of Four Population-Based Databases. Eur. J. Pain 2025, 29, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, A.; Machado, L. Cognitive Functioning in Females with Endometriosis-Associated Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Literature Review. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 2025, 40, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.R.; Elman, J.A.; Gustavson, D.E.; Lyons, M.J.; Fennema-Notestine, C.; Williams, M.E.; Panizzon, M.S.; Pearce, R.C.; Reynolds, C.A.; Sanderson-Cimino, M.; et al. History of chronic pain and opioid use is associated with cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. JINS 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.H.; Synnot, A.; Turner, T.; Simmonds, M.; Akl, E.A.; McDonald, S.; Salanti, G.; Meerpohl, J.; MacLehose, H.; Hilton, J.; et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction—The why, what, when, and how. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 91, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.M.; Davey, J.; Clarke, M.J.; Thompson, S.G.; Higgins, J.P. Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, I.J.; Wallace, B.C. Toward systematic review automation: A practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.-D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermelli, A.; Roveta, F.; Giorgis, L.; Boschi, S.; Grassini, A.; Ferrandes, F.; Lombardo, C.; Marcinno, A.; Rubino, E.; Rainero, I. Is headache a risk factor for dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Ahmed, W.L.; Liu, M.; Tu, S.; Zhou, F.; Wang, S. Contribution of pain to subsequent cognitive decline or dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 138, 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhan, Y.; Pei, J.; Fu, Q.; Wang, R.; Yang, Q.; Guan, Q.; Zhu, L. Migraine is a risk factor for dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Headache Pain 2025, 26, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Giustini, D.; De Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2016, 104, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Schoot, R.; De Bruin, J.; Schram, R.; Zahedi, P.; De Boer, J.; Weijdema, F.; Kramer, B.; Huijts, M.; Hoogerwerf, M.; Ferdinands, G. An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations; Updated October 2013; The GRADE Working Group: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A.; Carlin, J.B.; Stern, H.S.; Rubin, D.B. Bayesian Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A. Prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models (comment on article by Browne and Draper). Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P.-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chu, H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2018, 74, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, A.; Orsini, N. Dose-response meta-analysis of differences in means. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenland, S.; Longnecker, M.P. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehtari, A.; Gelman, A.; Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 2017, 27, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, F.; Gronau, Q.F.; Timmers, B.; Otte, W.M.; Ly, A.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Bayesian model-averaged meta-analysis in medicine. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 6743–6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.-R.; Nackley, A.; Huh, Y.; Terrando, N.; Maixner, W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Achariyar, T.M.; Li, B.; Liao, Y.; Mestre, H.; Hitomi, E.; Regan, S.; Kasper, T.; Peng, S.; Ding, F. Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 93, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, M.C.; Čeko, M.; Low, L.A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, O.; McGuire, B.E.; Finn, D.P. The effect of pain on cognitive function: A review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 93, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, M.; Goubert, D.; De Backer, F.; Struyf, F.; Hermans, L.; Coppieters, I.; De Wandele, I.; Da Silva, H.; Calders, P. Heart rate variability in patients with fibromyalgia and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 43, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; DeCarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsook, D. Neurological diseases and pain. Brain 2012, 135, 320–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | ((((Pain/OR Pain Perception/OR Chronic Pain/OR Neuralgia/OR ((Chronic) adj6 Pain* OR headache* OR Cephalalgia* OR Cephalodynia* OR neuropath* OR Arthritis/OR Back Pain/OR Complex Regional Pain Syndromes/OR Facial Neuralgia/OR Femoral Neuropathy/OR Fibromyalgia/OR Headache/OR Headache Disorders/OR Low Back Pain/OR Migraine Disorders/OR Musculoskeletal Pain/OR Myalgia/OR Myofascial Pain Syndromes/OR Neck Pain/OR Neuralgia/OR Osteoarthritis/OR Phantom Limb/OR Post-Traumatic Headache/OR Radial Neuropathy/OR Tension-type Headache/OR Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias/) OR ((pain[TIAB]) AND (arthrit*[TIAB] OR “complex regional pain”[TIAB] OR CRPS[TIAB] OR fibromyalgia[TIAB] OR headache*[TIAB] OR “low back pain”[TIAB] OR migrain*[TIAB] OR myalgia[TIAB] OR neuralgia[TIAB] or neuropath*[TIAB] OR nocicept*[TIAB] OR osteoarthrit*[TIAB] OR osteo-arthrit*[TIAB] OR “phantom limb”[TIAB] OR “reflex sympathetic dystrophy”[TIAB])) OR (central pain[TIAB] OR central sensitization[TIAB]))) AND ((Cognitive Dysfunction/OR Dementia/OR “Cognitive decline”[TIAB] OR “cognitive impairment”[TIAB] OR dementia [TIAB]))) AND ((((Epidemiologic Studies/OR Case–Control Studies/OR Cohort Studies/OR Cross-Sectional Studies/OR “case control” [TIAB] OR cohort [TIAB] OR prevalence[TIAB] OR incidence[TIAB]) AND (study [TIAB] OR studies [TIAB] OR analys*[TIAB] OR “follow up” [TIAB] OR observational [TIAB] OR uncontrolled [TIAB] OR non-randomized [TIAB] OR nonrandomized [TIAB] OR non randomized [TIAB] OR nonrandomized [TIAB] OR epidemiologic* [TIAB]))))) NOT (((letter [pt] OR editorial [pt] OR news [pt] OR historical article [pt] OR case reports [pt] OR letter [TI] OR comment* [TI] OR animal* [TI] OR “Animal Experimentation” [Mesh] OR “Animal Experimentation” [Mesh] OR “Rodentia” [Mesh] OR rats [TI] OR rat [TI] OR mouse [TI] OR mice [TI]))) |

| Embase | ((((Pain/de OR ‘Pain Perception’/de OR ‘Chronic Pain’/de OR Neuralgia/de OR ((Chronic) NEAR/6 Pain* OR headache* OR Cephalalgia* OR Cephalodynia* OR neuropath* OR Arthritis/de OR ‘Back Pain’/de OR ‘Complex Regional Pain Syndromes’/de OR ‘Facial Neuralgia’/de OR ‘Femoral Neuropathy’/de OR Fibromyalgia/de OR Headache/de OR ‘Headache Disorders’/de OR ‘Low Back Pain’/de OR ‘Migraine Disorders’/de OR ‘Musculoskeletal Pain’/de OR Myalgia/de OR ‘Myofascial Pain Syndromes’/de OR ‘Neck Pain’/de OR Neuralgia/de OR Osteoarthritis/de OR ‘Phantom Limb’/de OR ‘Post-Traumatic Headache’/de OR ‘Radial Neuropathy’/de OR ‘Tension-type Headache’/de OR ‘Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias’/de) OR ((pain:ti,ab) AND (arthrit*:ti,ab OR ‘complex regional pain’:ti,ab OR CRPS:ti,ab OR fibromyalgia:ti,ab OR headache*:ti,ab OR ‘low back pain’:ti,ab OR migrain*:ti,ab OR myalgia:ti,ab OR neuralgia:ti,ab OR neuropath*:ti,ab OR nocicept*:ti,ab OR osteoarthrit*:ti,ab OR osteo-arthrit*:ti,ab OR ‘phantom limb’:ti,ab OR ‘reflex sympathetic dystrophy’:ti,ab)) OR (‘central pain’:ti,ab OR ‘central sensitization’:ti,ab))) AND ((‘Cognitive Dysfunction’/de OR Dementia/de OR ‘Cognitive decline’:ti,ab OR ‘cognitive impairment’:ti,ab OR dementia:ti,ab))) AND ((((‘Epidemiologic Studies’/de OR ‘Case–Control Studies’/de OR ‘Cohort Studies’/de OR ‘Cross-Sectional Studies’/de OR ‘case control’:ti,ab OR cohort:ti,ab OR prevalence:ti,ab OR incidence:ti,ab) AND (study:ti,ab OR studies:ti,ab OR analys*:ti,ab OR ‘follow up’:ti,ab OR observational:ti,ab OR uncontrolled:ti,ab OR non-randomized:ti,ab OR nonrandomized:ti,ab OR ‘non randomized’:ti,ab OR nonrandomized:ti,ab OR epidemiologic*:ti,ab))))) NOT (((term:it OR term:it OR term:it OR term:it OR term:it OR letter:ti OR comment*:ti OR animal*:ti OR ‘Animal Experimentation’/exp OR ‘Animal Experimentation’/exp OR Rodentia/exp OR rats:ti OR rat:ti OR mouse:ti OR mice:ti))) |

| Central | (((([mh ^Pain] OR [mh ^“Pain Perception”] OR [mh ^“Chronic Pain”] OR [mh ^Neuralgia] OR ((Chronic) NEAR/6 Pain* OR headache* OR Cephalalgia* OR Cephalodynia* OR neuropath* OR [mh ^Arthritis] OR [mh ^“Back Pain”] OR [mh ^“Complex Regional Pain Syndromes”] OR [mh ^“Facial Neuralgia”] OR [mh ^“Femoral Neuropathy”] OR [mh ^Fibromyalgia] OR [mh ^Headache] OR [mh ^“Headache Disorders”] OR [mh ^“Low Back Pain”] OR [mh ^“Migraine Disorders”] OR [mh ^“Musculoskeletal Pain”] OR [mh ^Myalgia] OR [mh ^“Myofascial Pain Syndromes”] OR [mh ^“Neck Pain”] OR [mh ^Neuralgia] OR [mh ^Osteoarthritis] OR [mh ^“Phantom Limb”] OR [mh ^“Post-Traumatic Headache”] OR [mh ^“Radial Neuropathy”] OR [mh ^“Tension-type Headache”] OR [mh ^“Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias”]) OR ((pain:ti,ab) AND (arthrit*:ti,ab OR “complex regional pain”:ti,ab OR CRPS:ti,ab OR fibromyalgia:ti,ab OR headache*:ti,ab OR “low back pain”:ti,ab OR migrain*:ti,ab OR myalgia:ti,ab OR neuralgia:ti,ab OR neuropath*:ti,ab OR nocicept*:ti,ab OR osteoarthrit*:ti,ab OR osteo-arthrit*:ti,ab OR “phantom limb”:ti,ab OR “reflex sympathetic dystrophy”:ti,ab)) OR (“central pain”:ti,ab OR “central sensitization”:ti,ab))) AND (([mh ^“Cognitive Dysfunction”] OR [mh ^Dementia] OR “Cognitive decline”:ti,ab OR “cognitive impairment”:ti,ab OR dementia:ti,ab))) AND (((([mh ^“Epidemiologic Studies”] OR [mh ^“Case–Control Studies”] OR [mh ^“Cohort Studies”] OR [mh ^“Cross-Sectional Studies”] OR “case control”:ti,ab OR cohort:ti,ab OR prevalence:ti,ab OR incidence:ti,ab) AND (study:ti,ab OR studies:ti,ab OR analys*:ti,ab OR “follow up”:ti,ab OR observational:ti,ab OR uncontrolled:ti,ab OR non-randomized:ti,ab OR nonrandomized:ti,ab OR “non randomized”:ti,ab OR nonrandomized:ti,ab OR epidemiologic*:ti,ab))))) NOT (((letter:pt OR editorial:pt OR news:pt OR “historical article”:pt OR “case reports”:pt OR letter:ti OR comment*:ti OR animal*:ti OR [mh “Animal Experimentation”] OR [mh “Animal Experimentation”] OR [mh Rodentia] OR rats:ti OR rat:ti OR mouse:ti OR mice:ti))) |

| Web of Science | ((((Pain OR “Pain Perception” OR “Chronic Pain” OR Neuralgia OR ((Chronic) NEAR/6 Pain* OR headache* OR Cephalalgia* OR Cephalodynia* OR neuropath* OR Arthritis OR “Back Pain” OR “Complex Regional Pain Syndromes” OR “Facial Neuralgia” OR “Femoral Neuropathy” OR Fibromyalgia OR Headache OR “Headache Disorders” OR “Low Back Pain” OR “Migraine Disorders” OR “Musculoskeletal Pain” OR Myalgia OR “Myofascial Pain Syndromes” OR “Neck Pain” OR Neuralgia OR Osteoarthritis OR “Phantom Limb” OR “Post-Traumatic Headache” OR “Radial Neuropathy” OR “Tension-type Headache” OR “Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias”) OR ((pain) AND (arthrit* OR “complex regional pain” OR CRPS OR fibromyalgia OR headache* OR “low back pain” OR migrain* OR myalgia OR neuralgia OR neuropath* OR nocicept* OR osteoarthrit* OR osteo-arthrit* OR “phantom limb” OR “reflex sympathetic dystrophy”)) OR (“central pain” OR “central sensitization”))) AND ((“Cognitive Dysfunction” OR Dementia OR “Cognitive decline” OR “cognitive impairment” OR dementia))) AND ((((“Epidemiologic Studies” OR “Case–Control Studies” OR “Cohort Studies” OR “Cross-Sectional Studies” OR “case control” OR cohort OR prevalence OR incidence) AND (study OR studies OR analys* OR “follow up” OR observational OR uncontrolled OR non-randomized OR nonrandomized OR “non randomized” OR nonrandomized OR epidemiologic*))))) NOT (((letter OR editorial OR news OR “historical article” OR “case reports” OR letter OR comment* OR animal* OR “Animal Experimentation” OR “Animal Experimentation” OR Rodentia OR rats OR rat OR mouse OR mice))) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Machado Filardi, R.; Yoon, E.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.F.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Perin, J.P.; de Melo, P.S.; Leite, M.; Silva, L.; Navarro-Flores, A. The Silent Cognitive Burden of Chronic Pain: Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Living Dose–Response Bayesian Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197030

Pacheco-Barrios K, Machado Filardi R, Yoon E, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LF, Ribeiro JV, Perin JP, de Melo PS, Leite M, Silva L, Navarro-Flores A. The Silent Cognitive Burden of Chronic Pain: Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Living Dose–Response Bayesian Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197030

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco-Barrios, Kevin, Rafaela Machado Filardi, Edward Yoon, Luis Fernando Gonzalez-Gonzalez, Joao Victor Ribeiro, Joao Pedro Perin, Paulo S. de Melo, Marianna Leite, Luisa Silva, and Alba Navarro-Flores. 2025. "The Silent Cognitive Burden of Chronic Pain: Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Living Dose–Response Bayesian Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197030

APA StylePacheco-Barrios, K., Machado Filardi, R., Yoon, E., Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L. F., Ribeiro, J. V., Perin, J. P., de Melo, P. S., Leite, M., Silva, L., & Navarro-Flores, A. (2025). The Silent Cognitive Burden of Chronic Pain: Protocol for an AI-Enhanced Living Dose–Response Bayesian Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14197030