A Contemporary Narrative Review of Sodium Homeostasis Mechanisms, Dysnatraemia, and the Clinical Relevance in Adult Critical Illness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Sodium Haemostasis

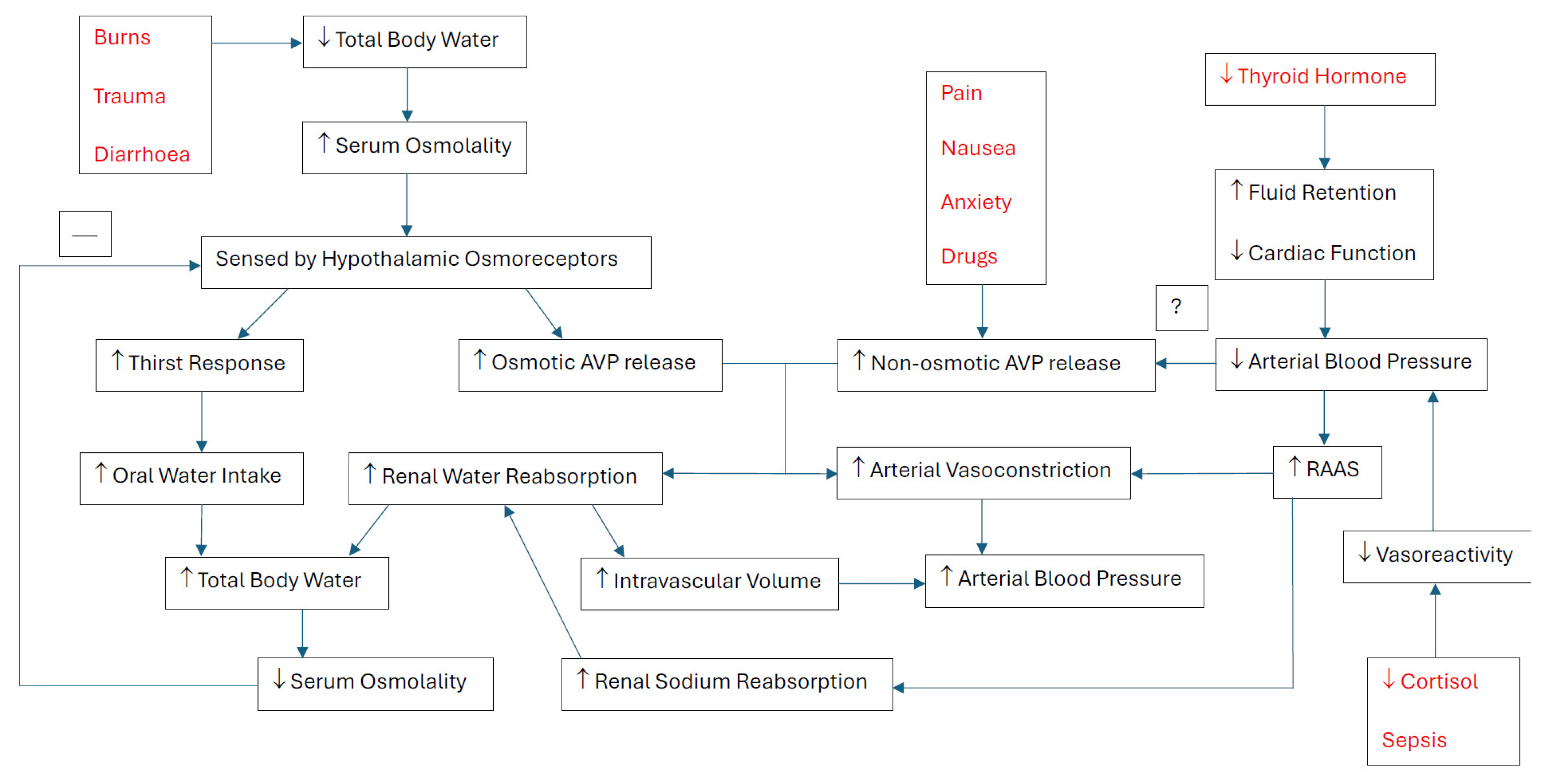

3.1. Osmoregulation

3.2. Non-Osmotic–AVP Release

3.3. Angiotensin II and Aldosterone

3.4. Cortisol and Thyroid Function

4. Dysnatraemia

4.1. Categories, Causes, and ICU Epidemiology

4.2. Physiological Effects

4.3. Clinical Outcomes

5. Ongoing Challenges

5.1. Sodium Measurement Techniques

5.2. Diagnostic Workup

5.3. Tailoring Management

5.4. Rate of Correcting Serum Sodium Concentration

5.5. Gaps in Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Pokaharel, M.; Block, C.A. Dysnatremia in the ICU. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2011, 17, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygun, D.A. Sodium and brain injury: Do we know what we are doing? Crit. Care 2009, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, M.J.; Thompson, C.J. Neurosurgical Hyponatremia. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, P.; Lin, J.; Teng, J.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X. Dysnatremia is an Independent Indicator of Mortality in Hospitalized Patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 2408–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, Y.; Rother, S.; Ferreira, A.M.; Ewald, C.; Dünisch, P.; Riedemmann, N.; Reinhart, K. Fluctuations in serum sodium level are associated with an increased risk of death in surgical ICU patients. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.; Jaber, B.L.; Price, L.L.; Upadhyay, A.; Madias, N.E. Impact of hospital-associated hyponatremia on selected outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.C.; Salciccioli, J.D.; Goodson, R.J.; Pimentel, M.A.; Sun, K.Y.; Celi, L.A.; Shalhoub, J. The association between sodium fluctuations and mortality in surgical patients requiring intensive care. J. Crit. Care 2017, 40, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topjian, A.A.; Stuart, A.; Pabalan, A.A.; Clair, A.; Kilbaugh, T.J.; Abend, N.S.; Storm, P.B.; Berg, R.A.; Huh, J.W.; Friess, S.H. Greater fluctuations in serum sodium levels are associated with increased mortality in children with externalized ventriculostomy drains in a PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 15, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, G.; Ferraro, P.M.; Calvaruso, L.; Naticchia, A.; D’Alonzo, S.; Gambaro, G. Sodium Fluctuations and Mortality in a General Hospitalized Population. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2019, 44, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.C.; Chow, V.; Yong, A.S.; Chung, T.; Kritharides, L. Fluctuation of serum sodium and its impact on short and long-term mortality following acute pulmonary embolism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, M.E.; Tso, M.K.; Macdonald, R.L. Significance of fluctuations in serum sodium levels following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: An exploratory analysis. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 131, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, W.S.; Bezerra, D.A.; Amorim, R.L.; Figueiredo, E.G.; Tavares, W.M.; De Andrade, A.F.; Teixeira, M.J. Serum sodium disorders in patients with traumatic brain injury. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2011, 7, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, D.; Tazmini, K.; Jacobsen, D. Acute Dysnatremias—A dangerous and overlooked clinical problem. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2019, 27, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumin, J.; DiBartola, S.P. Disorders of Sodium and Water Homeostasis. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2017, 47, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Hall, J.E. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, 14th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Chapter 29. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, M.L.; Bohn, D. Clinical approach to disorders of salt and water balance. Emphasis on integrative physiology. Crit. Care Clin. 2002, 18, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knepper, M.A.; Kwon, T.H.; Nielsen, S. Molecular physiology of water balance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, R.W. Water and sodium retention in edematous disorders: Role of vasopressin and aldosterone. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, S47–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, F.O. Sodium intake, body sodium, and sodium excretion. Lancet 1988, 2, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, C.A.; Huey, E.L.; Ahn, J.S.; Beutler, L.R.; Tan, C.L.; Kosar, S.; Bai, L.; Chen, Y.; Corpuz, T.V.; Madisen, L.; et al. A gut-to-brain signal of fluid osmolarity controls thirst satiation. Nature 2019, 568, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, C.A.; Leib, D.E.; Knight, Z.A. Neural circuits underlying thirst and fluid homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimizu, T.A.; Nakamura, K.; Egashira, N.; Hiroyama, M.; Nonoguchi, H.; Tanoue, A. Vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors: From molecules to physiological systems. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1813–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, Y.; Uede, T.; Ishiguro, M.; Honda, O.; Honmou, O.; Kato, T.; Wanibuchi, M. Pathogenesis of hyponatremia following subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Surg. Neurol. 1996, 46, 500–507; discussion 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isotani, E.; Suzuki, R.; Tomita, K.; Hokari, M.; Monma, S.; Marumo, F.; Hirakawa, K. Alterations in plasma concentrations of natriuretic peptides and antidiuretic hormone after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 1994, 25, 2198–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendes, E.; Walter, M.; Cullen, P.; Prien, T.; Van Aken, H.; Horsthemke, J.; Schulte, M.; von Wild, K.; Scherer, R. Secretion of brain natriuretic peptide in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 1997, 349, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E.; Fauci, A.; Kasper, D.L.; Hauser, S.L.; Longo, D.L.; Jameson, J.L. (Eds.) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 15th ed.; McGraw-Hill Inc.: Columbus, OH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Claussen, M.S.; Landercasper, J.; Cogbill, T.H. Acute adrenal insufficiency presenting as shock after trauma and surgery: Three cases and review of the literature. J. Trauma 1992, 32, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docci, D.; Cremonini, A.M.; Nasi, M.T.; Baldrati, L.; Capponcini, C.; Giudicissi, A.; Neri, L.; Feletti, C. Hyponatraemia with natriuresis in neurosurgical patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2000, 15, 1707–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Shin, Y.S.; Ahn, S.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, E.J.; Chang, Y.S.; Bang, B.K. Thyroxine treatment induces upregulation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system due to decreasing effective plasma volume in patients with primary myxoedema. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Overgaard-Steensen, C.; Ring, T. Clinical review: Practical approach to hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2013, 17, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzoulis, P.; Evans, R.; Falinska, A.; Barnard, M.; Tan, T.; Woolman, E.; Leyland, R.; Martin, N.; Edwards, R.; Scott, R.; et al. Multicentre study of investigation and management of inpatient hyponatraemia in the UK. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 90, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, R.; Baldeweg, S.E.; Wilson, S.R. Sodium disorders in neuroanaesthesia and neurocritical care. BJA Educ. 2022, 22, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, A.; Jaber, B.L.; Madias, N.E. Epidemiology of hyponatremia. Semin. Nephrol. 2009, 29, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Lansink-Hartgring, A.; Hessels, L.; Weigel, J.; de Smet, A.; Gommers, D.; Panday, P.V.N.; Hoorn, E.J.; Nijsten, M.W. Long-term changes in dysnatremia incidence in the ICU: A shift from hyponatremia to hypernatremia. Ann. Intensive Care 2016, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, O.; Chapalain, X.; Vermeersch, V.; Moyer, J.D.; Lasocki, S.; Cohen, B.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Chalard, K.; Seguin, P.; Hourmant, Y.; et al. Impact of continuous hypertonic (NaCl 20%) saline solution on renal outcomes after traumatic brain injury (TBI): A post hoc analysis of the COBI trial. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, E.U.; Waheed, S.; Perveen, F.; Daniyal, M.; Raffay Khan, M.A.; Siddiqui, S.; Siddiqui, Z. Clinical outcome of paediatric patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) receiving 3% hypertonic saline (HTS) in the emergency room of a tertiary care hospital. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1741–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, E.; Nieboer, D.; Kompanje, E.J.O.; Citerio, G.; Stocchetti, N.; Gommers, D.; Menon, D.K.; Ercole, A.; Maas, A.I.R.; Lingsma, H.F.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Mannitol Versus Hypertonic Saline in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A CENTER-TBI Study. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, G.C.; Lindner, G.; Druml, W.; Metnitz, B.; Schwarz, C.; Bauer, P.; Metnitz, P.G. Incidence and prognosis of dysnatremias present on ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, S.L.; Abouqal, R.; Zeggwagh, A.A.; Madani, N.; Abidi, K.; Zekraoui, A.; Kerkeb, O. Incidence, causes and prognostic factors of hyponatremia in intensive care. Rev. Med. Interne 2003, 24, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, G.; Funk, G.C.; Schwarz, C.; Kneidinger, N.; Kaider, A.; Schneeweiss, B.; Kramer, L.; Druml, W. Hypernatremia in the critically ill is an independent risk factor for mortality. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007, 50, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorn, E.J.; Betjes, M.G.; Weigel, J.; Zietse, R. Hypernatraemia in critically ill patients: Too little water and too much salt. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, M.; Timsit, J.F.; Francais, A.; Nguile-Makao, M.; Adrie, C.; Cohen, Y.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Goldgran-Toledano, D.; Dumenil, A.S.; Jamali, S.; et al. Association between hypernatraemia acquired in the ICU and mortality: A cohort study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 2510–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, H.T.; Ahmed, S.B.; Zygun, D.; Khandwala, F.; Laupland, K. Characterization of intensive care unit acquired hyponatremia and hypernatremia following cardiac surgery. Can. J. Anaesth. 2010, 57, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikar, S.S.; Mount, D.B.; Curhan, G.C. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, U.; Picetti, E.; Antonucci, E.; Parenti, E.; Regolisti, G.; Mergoni, M.; Vezzani, A.; Cabassi, A.; Fiaccadori, E. The relation between the incidence of hypernatremia and mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyagari, V.; Deibert, E.; Diringer, M.N. Hypernatremia in the neurologic intensive care unit: How high is too high? J. Crit. Care 2006, 21, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, Y.H.; Chen, G. Hypernatremia severity and the risk of death after traumatic brain injury. Injury 2013, 44, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, M.; Pichon, M.; Schwebel, C.; Ruckly, S.; Adrie, C.; Haouache, H.; Azoulay, E.; Bouadma, L.; Clec’h, C.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; et al. Influence of early dysnatremia correction on survival of critically ill patients. Shock 2014, 41, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, C.; Patel, S.; Cheung, N.W. Admission sodium levels and hospital outcomes. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergheynst, F.; Sakr, Y.; Felleiter, P.; Hering, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Vanhems, P.; Taccone, F.S.; Vincent, J.L. Incidence and prognosis of dysnatraemia in critically ill patients: Analysis of a large prevalence study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile-Filho, A.; Menegueti, M.G.; Nicolini, E.A.; Lago, A.F.; Martinez, E.Z.; Auxiliadora-Martins, M. Are the Dysnatremias a Permanent Threat to the Critically Ill Patients? J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, B.; Han, Q.; Mengke, N.; He, K.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Zeng, H. Prognostic value of ICU-acquired hypernatremia in patients with neurological dysfunction. Medicine 2016, 95, e3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.B.; Hu, X.X.; Huang, X.F.; Liu, K.Q.; Yu, C.B.; Wang, X.M.; Ke, L. Risk Factors and Outcomes in Patients with Hypernatremia and Sepsis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 351, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimeski, G.; Morgan, T.J.; Presneill, J.J.; Venkatesh, B. Disagreement between ion selective electrode direct and indirect sodium measurements: Estimation of the problem in a tertiary referral hospital. J. Crit. Care 2012, 27, 326.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, G.B. Determination of sodium with ion-selective electrodes. Clin. Chem. 1981, 27, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortgens, P.; Pillay, T.S. Pseudohyponatremia revisited: A modern-day pitfall. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011, 135, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascarrou, J.B.; Ermel, C.; Cariou, A.; Laitio, T.; Kirkegaard, H.; Soreide, E.; Grejs, A.M.; Reinikainen, M.; Colin, G.; Taccone, F.S.; et al. Dysnatremia at ICU admission and functional outcome of cardiac arrest: Insights from four randomised controlled trials. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, R.W. Body fluid volume regulation in health and disease: A unifying hypothesis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesaka, J.K.; Imbriano, L.; Mattana, J.; Gallagher, D.; Bade, N.; Sharif, S. Differentiating SIADH from Cerebral/Renal Salt Wasting: Failure of the Volume Approach and Need for a New Approach to Hyponatremia. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, N.G.; Struck, J.; Alonso, C.; Bergmann, A. Assay for the measurement of copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the precursor of vasopressin. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wun, T. Vasopressin and platelets: A concise review. Platelets 1997, 8, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenske, W.K.; Schnyder, I.; Koch, G.; Walti, C.; Pfister, M.; Kopp, P.; Fassnacht, M.; Strauss, K.; Christ-Crain, M. Release and Decay Kinetics of Copeptin vs AVP in Response to Osmotic Alterations in Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, W.; Stork, S.; Blechschmidt, A.; Maier, S.G.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Allolio, B. Copeptin in the differential diagnosis of hyponatremia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, N.; Winzeler, B.; Suter-Widmer, I.; Schuetz, P.; Arici, B.; Bally, M.; Blum, C.A.; Nickel, C.H.; Bingisser, R.; Bock, A.; et al. Evaluation of copeptin and commonly used laboratory parameters for the differential diagnosis of profound hyponatraemia in hospitalized patients: ‘The Co-MED Study’. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 86, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorhout Mees, S.M.; Hoff, R.G.; Rinkel, G.J.; Algra, A.; van den Bergh, W.M. Brain natriuretic peptide concentrations after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relationship with hypovolemia and hyponatremia. Neurocrit. Care 2011, 14, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Tonog, P.; Lakhkar, A.D. Normal Saline; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, A.; Gowrishankar, M.; Abrahamson, S.; Mazer, C.D.; Feldman, R.D.; Halperin, M.L. Postoperative hyponatremia despite near-isotonic saline infusion: A phenomenon of desalination. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 126, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, T.S.; Patel, P. Desmopressin; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, G.; Funk, G.C. Hypernatremia in critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care 2013, 28, 216.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khositseth, S.; Charngkaew, K.; Boonkrai, C.; Somparn, P.; Uawithya, P.; Chomanee, N.; Payne, D.M.; Fenton, R.A.; Pisitkun, T. Hypercalcemia induces targeted autophagic degradation of aquaporin-2 at the onset of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1070–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khositseth, S.; Uawithya, P.; Somparn, P.; Charngkaew, K.; Thippamom, N.; Hoffert, J.D.; Saeed, F.; Michael Payne, D.; Chen, S.H.; Fenton, R.A.; et al. Autophagic degradation of aquaporin-2 is an early event in hypokalemia-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ-Crain, M.; Gaisl, O. Diabetes insipidus. Presse Med. 2021, 50, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, M.H. Lixivaptan: A vasopressin receptor antagonist for the treatment of hyponatremia. Kidney Int. 2012, 82, 1154–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmodin, L.; Sekhon, M.S.; Henderson, W.R.; Turgeon, A.F.; Griesdale, D.E. Hypernatremia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Ann. Intensive Care 2013, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterns, R.H.; Nigwekar, S.U.; Hix, J.K. The treatment of hyponatremia. Semin. Nephrol. 2009, 29, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterns, R.H.; Silver, S.M. Cerebral salt wasting versus SIADH: What difference? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasovski, G.; Vanholder, R.; Allolio, B.; Annane, D.; Ball, S.; Bichet, D.; Decaux, G.; Fenske, W.; Hoorn, E.J.; Ichai, C.; et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29 (Suppl. S2), i1–i39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbalis, J.G.; Goldsmith, S.R.; Greenberg, A.; Korzelius, C.; Schrier, R.W.; Sterns, R.H.; Thompson, C.J. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: Expert panel recommendations. Am. J. Med. 2013, 126 (Suppl. S1), S1–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, R.; Chand, R.; Goldfarb, D.S. Hypernatremia in the intensive care unit. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2022, 31, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, J.J.; Tong, N.W.; Guo, X.H.; Qiu, M.C.; Yang, G.Y.; Liu, Z.M.; Ma, J.H.; Zhang, Z.W.; Gu, F. Randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tolvaptan in Chinese patients with hyponatremia caused by SIADH. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 54, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahudeen, A.K.; Ali, N.; George, M.; Lahoti, A.; Palla, S. Tolvaptan in hospitalized cancer patients with hyponatremia: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial on efficacy and safety. Cancer 2014, 120, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, R.W.; Gross, P.; Gheorghiade, M.; Berl, T.; Verbalis, J.G.; Czerwiec, F.S.; Orlandi, C.; Investigators, S. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2099–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Jo, Y.H.; Ahn, S.; Medina-Liabres, K.; Oh, Y.K.; Lee, J.B.; Kim, S. Risk of Overcorrection in Rapid Intermittent Bolus vs Slow Continuous Infusion Therapies of Hypertonic Saline for Patients with Symptomatic Hyponatremia: The SALSA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Haraoka, J.; Hirabayashi, H.; Kawamata, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Kitahara, T.; Kojima, J.; Kuroiwa, T.; Mori, T.; Moro, N.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of hydrocortisone against hyponatremia in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2007, 38, 2373–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares, W.; Aramendi, I.; Langlois, P.L.; Biestro, A. Hyponatremia in the neurocritical care patient: An approach based on current evidence. Med. Intensiv. 2015, 39, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hyponatraemia | Hypernatraemia |

|---|---|

| Hypertonic (>285 mOsm/L) Hyperglycaemia Mannitol * Isotonic (275–285 mOsm/L) Hyperproteinaemia Hyperlipidaemia Hypotonic (<275 mOsm/L) SIADH CSW Addison’s Disease Diuretics Desmopressin Hypotonic Fluid Therapy Acute Kidney Injury Severe Hypothyroidism Severe Vomiting Severe Diarrhoea | High Urine Volume (>3 L/24 h) Diabetes Insipidus Hypertonic Saline Osmotic Diuresis (e.g., Mannitol) Low Urine Volume (<3 L/24 h) Low level of consciousness/no access to water Severe Burns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raman, V.; Ramanan, M.; Edwards, F.; Laupland, K.B. A Contemporary Narrative Review of Sodium Homeostasis Mechanisms, Dysnatraemia, and the Clinical Relevance in Adult Critical Illness. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196914

Raman V, Ramanan M, Edwards F, Laupland KB. A Contemporary Narrative Review of Sodium Homeostasis Mechanisms, Dysnatraemia, and the Clinical Relevance in Adult Critical Illness. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196914

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaman, Vignesh, Mahesh Ramanan, Felicity Edwards, and Kevin B. Laupland. 2025. "A Contemporary Narrative Review of Sodium Homeostasis Mechanisms, Dysnatraemia, and the Clinical Relevance in Adult Critical Illness" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196914

APA StyleRaman, V., Ramanan, M., Edwards, F., & Laupland, K. B. (2025). A Contemporary Narrative Review of Sodium Homeostasis Mechanisms, Dysnatraemia, and the Clinical Relevance in Adult Critical Illness. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196914