Sexuality and Related Disorders in OCD and Their Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

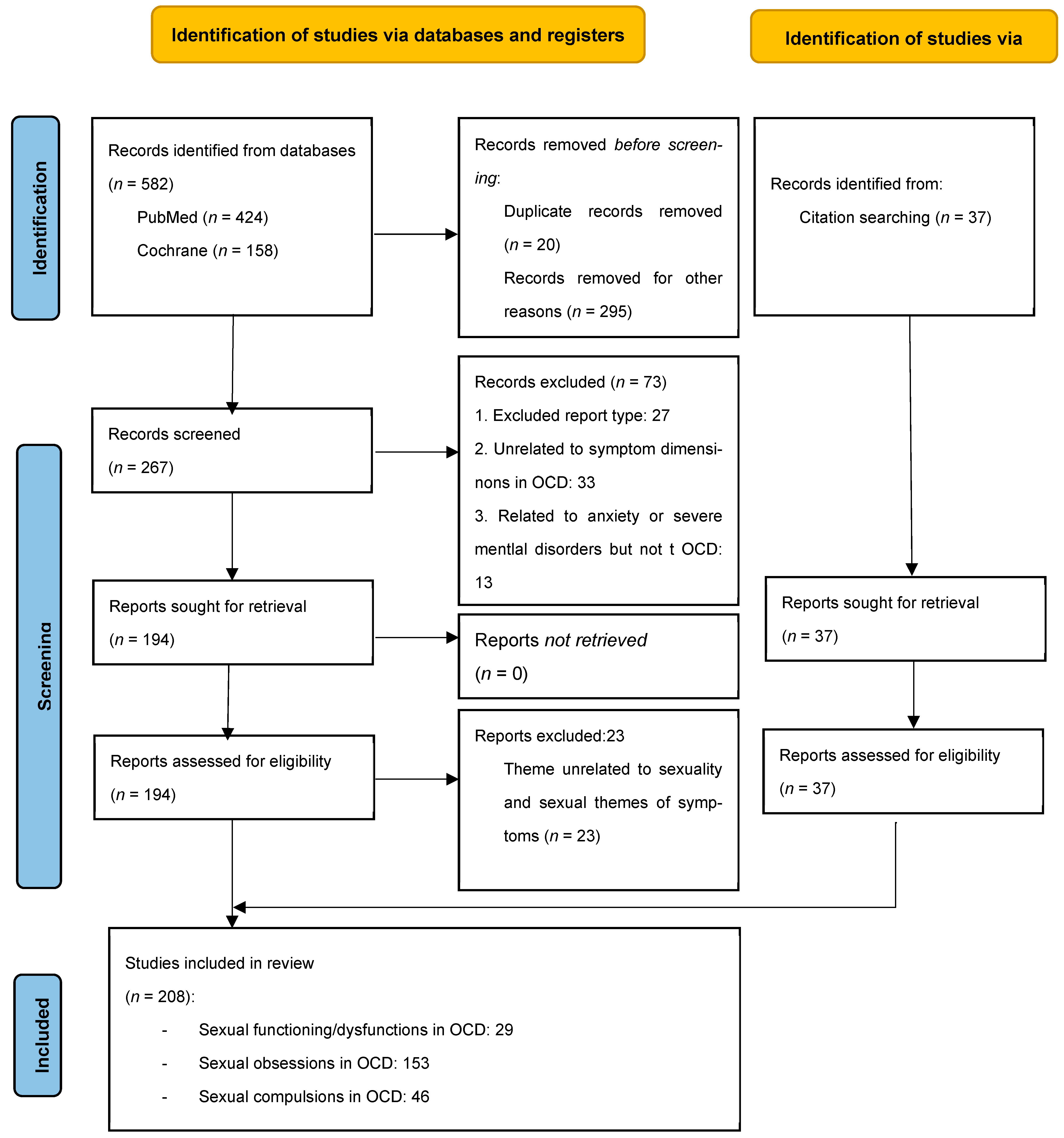

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- P (Population/Problem): Patients diagnosed with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), including both adults and adolescents, particularly those exhibiting sexual symptom dimensions. We aimed to include the widest possible variety of OCD presentations to examine how symptomatology related to sexual functioning and impairment. No age or demographic restrictions were applied, in order to capture evidence on sexual symptoms and impairment in OCD across diverse populations and to account for predictable variability.

- -

- I (Intervention/Exposure): Presence of sexual dysfunctions, sexual obsessions, sexual compulsions, and compulsive sexual behavior within the OCD spectrum.

- -

- C (Comparison): General population and individuals diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions (e.g., major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and schizophrenia).

- -

- O (Outcome): Altered sexual functioning (e.g., libido, arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction), psychological distress and functional impairment, treatment response (e.g., CBT, SSRIs, EMDR, and DBS), and neurobiological and cognitive correlates.

- Inclusion criteria

- Titles or abstracts referring to sexual functioning in OCD. During title or abstract screening, every title referring to sexual functioning or dysfunction in severe mental disorders or anxiety disorder was included for further assessment.

- Titles/abstracts about symptom dimensions and OCD, including obsessions and compulsions.

- Titles or abstracts including symptoms or phenomena in the sphere of OCD, such as “subthreshold obsessional symptoms” or “mental contamination/pollution”.

- Titles/abstracts concerning OCD, not limited to a concrete aspect of the illness or the patient’s lives other than sexuality or sexually themed symptoms.

- The studies assessed had to be categorized as a meta-analysis; a systematic or narrative review; or an experimental (randomized clinical trials), observational (case–control, cohort studies), or descriptive study (excluding case reports/series, except in animals).

- Exclusion criteria

- Case reports, series of cases, studies in animals, correspondences, editorials, and any other types of study not listed within the inclusion criteria.

- Studies concerned with sexuality but not mental disorders, or with a specific aspect of mental illness or OCD unrelated to sexuality.

- Articles specifically about sexual dysfunctions caused by the treatment of OCD, i.e., sexual dysfunction that is secondary to treatment with clomipramine or serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) for OCD.

- Studies concerned with sexuality in other specified mental disorders other than OCD.

- Papers concerning OCD but focusing on other symptoms other than those that are sexually themed (for example, only measuring the general severity of the symptoms without addressing sexual obsessions or taboo/unacceptable thoughts separately).

- Statistical signification is either not clearly stated and justified via statistical analysis or inference in reports establishing associations between variables, or the methods to identify the association are not specified.

3. Results

3.1. Sexual Functioning in Obsessive-Compulsive Patients

3.1.1. Sexual Development

3.1.2. Social and Marital Difficulties

3.1.3. Sexual Excitation and Inhibition Within the Dual-Control Model

3.1.4. Sexual Dysfunction and Dissatisfaction

Low Frequency

Aversion, Avoidance, and Impaired Sexual Desire

Arousal

Erectile Dysfunction and Premature Ejaculation

Orgasm Dysfunction, Lack of Pleasure, and Pain During Intercourse

Dissatisfaction

3.2. Sexual Obsessions

3.2.1. Definition of Sexual Obsessions

3.2.2. Epidemiology

3.2.3. Clinical Course

3.2.4. Psychological Patterns, Beliefs, and Upbringing

3.2.5. Neurobiological Correlations

3.2.6. Association with Other Obsessions

3.2.7. Association with Other Pathologies

3.2.8. Subtypes of Sexual OCD

3.2.9. Impact of Sexual OCD

3.2.10. Treatment of Sexual OCD

3.3. Compulsions Related to Sexuality in OCD Symptoms

3.3.1. Compulsions Related to Sexual Obsessions

3.3.2. Compulsive/Addictive Sexual Behavior and OCD

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- The connections between sexual obsessions and impairment of sexual functioning in people with OCD.

- -

- Specific social and gender-related factors behind sexual obsessions in OCD could better determine its etiology and perhaps bring a better understanding of these symptoms.

- -

- Causes behind treatment refractoriness in sexual obsessions to gain more clarity beyond the conflicting results especially regarding cognitive therapies and treatment with SRIS.

- -

- Gaining deeper insight into the efficacy of treatments like DBS against more traditional approaches for specific subgroups of OCD like sexual OCD could support the enhancement of clinical guidelines to provide a more individualized treatment.

- -

- Specific psychotherapeutic approaches (Socratic dialogue, role-playing, acceptance and engaging therapy…) would benefit from more research in these specific cases, and possible provide evidence for structured therapeutical alternatives.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASQ | DPSS-R DS Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale–Revised, which evaluates disgust propensity (DP) and disgust sensitivity (DS). |

| GAD | Generalized Anxiety Disorder. |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model. |

| OBQ-46 | Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire 46. |

| OCI-R | Obsessive Compulsive Inventory—Revised. |

| PD | Panic Disorder. |

| SO | Sexual Obsessions. |

| SD | Sexual Dysfunction. |

| SES | Sexual Excitation Score. |

| SIS | Sexual Inhibition Score—1: due to threat of performance failure; 2: due to threat of performance consequences. |

| r | Pearson’s Correlation. |

| SD | Standard Deviation. |

| SGRS | Sexual Guilt Rating Scale. |

| t | Student’s t. |

References

- Janardhan Reddy, Y.; Sundar, A.S.; Narayanaswamy, J.; Math, S. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Indian J. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, B. Depression and Risk of Suicide in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Hospital-Based Study. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2016, 25, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Minnen, A.; Kampman, M. The Interaction between Anxiety and Sexual Functioning: A Controlled Study of Sexual Functioning in Women with Anxiety Disorders. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2000, 15, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, B.; Steketee, G. Sexual History, Attitudes and Functioning of Obsessive-Compulsive Patients. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1989, 15, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real, E.; Montejo, Á.; Alonso, P.; Manuel Menchón, J. Sexuality and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The Hidden Affair. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 3, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 9789386217967. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, T.; Sharma, M.P.; Thennarasu, K.; Reddy, Y.C.J. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Obsessive Beliefs. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2015, 37, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Marques, L.; Hinton, D.E.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Z.P. Symptom Dimensions in Chinese Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2009, 15, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; LaSalle-Ricci, V.H.; Ronquillo, J.G.; Crawley, S.A.; Cochran, L.W.; Kazuba, D.; Greenberg, B.D.; Murphy, D.L. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptom Dimensions Show Specific Relationships to Psychiatric Comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 135, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, R.C.; Ramos-Cerqueira, A.T.A.; Shavitt, R.G.; do Rosário, M.C.; de Mathis, M.A.; Miguel, E.C.; Torres, A.R. Symptom Dimensions, Clinical Course and Comorbidity in Men and Women with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 209, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, W.K.; Price, L.H.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Mazure, C.; Fleischmann, R.L.; Hill, C.L.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: I. Development, Use, and Reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1989, 46, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scahill, L.; Riddle, M.A.; McSwiggin-Hardin, M.; Ort, S.I.; King, R.A.; Goodman, W.K.; Cicchetti, D.; Leckman, J.F. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and Validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Cremades, F.; Simonelli, C.; Montejo, A.L. Sexual Disorders beyond DSM-5. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, V.B.; Raute, N.J.; McConeville, B.J.; McElroy, S.L. An Adolescent Male with Multiple Paraphilias Successfully Treated with Fluoxetine. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, I.M.; Mataix-Cols, D. Four-Year Remission of Transsexualism after Comorbid Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder Improved with Self-Exposure Therapy. Case Report. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 171, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perilstein, R.D.; Lipper, S.; Friedman, L.J. Three Cases of Paraphilias Responsive to Fluoxetine Treatment. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1991, 52, 169–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mick, T.M.; Hollander, E. Impulsive-Compulsive Sexual Behavior. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.W.; Kehrberg, L.L.D.; Flumerfelt, D.L.; Schlosser, S.S. Characteristics of 36 Subjects Reporting Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, A.; Fogel, Y.A.; Reid, R.C.; Potenza, M.N. Should Hypersexual Disorder Be Classified as an Addiction? Sex. Addict. Compulsivity 2013, 20, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.D.; Thibaut, F. Sexual Addictions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abus. 2010, 36, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N.C.; Coleman, E.; Miner, M.H. Psychiatric Comorbidity and Compulsive/Impulsive Traits in Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Compr. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Farris, S.G.; Turkheimer, E.; Pinto, A.; Ozanick, K.; Franklin, M.E.; Liebowitz, M.; Simpson, H.B.; Foa, E.B. Myth of the Pure Obsessional Type in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández De La Cruz, L.; Barrow, F.; Bolhuis, K.; Krebs, G.; Volz, C.; Nakatani, E.; Heyman, I.; Mataix-Cols, D. Sexual Obsessions in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, U.M.; Aksoy, S.G.; Maner, F.; Gokalp, P.; Yanik, M. Sexual Dysfunction in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Panic Disorder. Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohi, K.; Kuramitsu, A.; Fujikane, D.; Takai, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Shioiri, T. Shared Genetic Basis between Reproductive Behaviors and Anxiety-Related Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4103–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staebler, C.R.; Alec Pollard, C.; Merkel, W.T. Sexual History and Quality of Current Relationships in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Comparison with Two Other Psychiatric Samples. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1993, 19, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezahler, A.; Kuckertz, J.M.; McKay, D.; Falkenstein, M.J.; Feinstein, B.A. Emotion Regulation and OCD among Sexual Minority People: Identifying Treatment Targets. J. Anxiety Disord. 2024, 101, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenelle, L.F.; De Souza, W.F.; De Menezes, G.B.; Mendlowicz, M.V.; Miotto, R.R.; Falcão, R.; Versiani, M.; Figueira, I.L. Sexual Function and Dysfunction in Brazilian Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steketee, G. Disability and Family Burden in Obsessive—Compulsive Disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 1997, 42, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żerdziński, M.; Burdzik, M.; Żmuda, R.; Witkowska-Berek, A.; Dȩbski, P.; Flajszok-Macierzyńska, N.; Piegza, M.; John-Ziaja, H.; Gorczyca, P. Sense of Happiness and Other Aspects of Quality of Life in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1077337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, R.D.; Clopton, J.R.; Humphreys, J.D. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Romantic Functioning. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, A.; Marazziti, D.; Mucci, F.; Dèttore, D. Propensity to Sexual Response among Adults with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2019, 15, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, A.; Marazziti, D.; Mucci, F.; Angelo, N.L.; Prestia, D.; Dèttore, D. Sexual Response in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The Role of Obsessive Beliefs. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, A.; Angelo, N.L.; Prestia, D.; Dèttore, D. The Role of Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity on Sexual Excitation and Inhibition in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. In Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome; PAGEPress Publications: Pavia, Italy, 2019; Volume 22, pp. 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, S.J.; Strathdee, S.A.; Zians, J.; McQuaid, J.; Patterson, T.L. Correlates of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Sample of HIV-Positive, Methamphetamine-Using Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, A.; Marazziti, D.; Mucci, F.; Grassi, G.; Prestia, D.; Dèttore, D. Sexual Arousal in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with and without Contamination/Washing Symptoms a Moderating Role of Disgust Sensitivity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dèttore, D.; Angelo, N.L.; Marazziti, D.; Mucci, F.; Prestia, D.; Pozza, A. A Pilot Study of Gender Differences in Sexual Arousal of Patients With OCD: The Moderator Roles of Attachment and Contamination Symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 609989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Tarafder, S.; Bilimoria, D.D.; Paul, D.; Bandyopadhyay, G. Instinctual Impulses in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Neuropsychological and Psychoanalytic Interface. Asian J. Psychiatry 2010, 3, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, A.; Melli, G.; Radomsky, A.S. Different Disgust Domains Specifically Relate to Mental and Contact Contamination Fear in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Evidence From a Path Analytic Model in an Italian Clinical Sample. Behav. Ther. 2019, 50, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghassemzadeh, H.; Raisi, F.; Firoozikhojastefar, R.; Meysamie, A.; Karamghadiri, N.; Nasehi, A.A.; Fallah, J.; Sorayani, M.; Ebrahimkhani, N. A Study on Sexual Function in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Patients With and Without Depressive Symptoms. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2017, 53, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, W.O.; Noshirvani, H.F.; Marks, I.M.; Lelliott, P.T. Anorgasmia from Clomipramine in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. A Controlled Trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 151, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herder, T.; Spoelstra, S.K.; Peters, A.W.M.; Knegtering, H. Sexual Dysfunction Related to Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Sex. Med. 2023, 20, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulink, N.C.C.; Denys, D.; Bus, L.; Westenberg, H.G.M. Sexual Pleasure in Women with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 91, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendurkar, A.; Kaur, B.W.; Kaur, M.; Agarwal, A.K.; Dhyani, M. Major Depressive Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Do the Sexual Dysfunctions Differ? Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 10, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksaray, G.; Yelken, B.; Kaptanoğlu, C.; Oflu, S.; Özaltin, M. Sexuality in Women with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2001, 27, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontek, A.; Szeja, J.; Błachut, M.; Badura-Brzoza, K. Sexual Problems in the Patients with Psychiatric Disorders. Wiad. Lek. 2019, 72, 1984–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, B.J.; Pujol, J.; Cardoner, N.; Deus, J.; Alonso, P.; López-Solà, M.; Contreras-Rodríguez, O.; Real, E.; Segalàs, C.; Blanco-Hinojo, L.; et al. Brain Corticostriatal Systems and the Major Clinical Symptom Dimensions of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, G.; Mizrahi, M.; Szepsenwol, O.; Derby, D. Right or Flawed: Relationship Obsessions and Sexual Satisfaction. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2218–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Ricca, V.; Bandini, E.; Mannucci, E.; Petrone, L.; Fisher, A.D.; Lotti, F.; Balercia, G.; Faravelli, C.; Forti, G.; et al. Association between Psychiatric Symptoms and Erectile Dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Soriano, G.; Belloch, A.; Morillo, C.; Clark, D.A. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: From Normal Cognitive Intrusions to Clinical Obsessions. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011, 25, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterneck, C.T.; Siev, J.; Adams, T.G.; Slimowicz, J.C.; Smith, A.H. Assessing Sexually Intrusive Thoughts: Parsing Unacceptable Thoughts on the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Behav. Ther. 2015, 46, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuty-Pachecka, M. Sexual Obsessions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Definitions, Models and Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snethen, C.; Warman, D.M. Effects of Psychoeducation on Attitudes towards Individuals with Pedophilic Sexual Intrusive Thoughts. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2018, 19, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.W.; Rouleau, T.M.; Turner, E.; Williams, M.T. Disgust Sensitivity Mediates the Link between Homophobia and Sexual Orientation Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2021, 50, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, B.; Jassi, A.; Heyman, I.; Turner, C.; Volz, C.; Krebs, G. Transformation Obsessions in Paediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Response to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2015, 48, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettess, Z.; Albertella, L.; Destree, L.; Rosário, M.C.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Miguel, E.C.; Fontenelle, L.F. Clinical Characteristics of Transformation Obsessions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Psychopathological Study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaisoorya, T.S.; Janardhan Reddy, Y.C.; Thennarasu, K.; Beena, K.V.; Beena, M.; Jose, D.C. An Epidemological Study of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Adolescents from India. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, M.; Ottoni, R.; Paglia, F.; Monici, A.; Ossola, P.; De Panfilis, C.; Marchesi, C. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in Schizophrenia and in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Differences and Similarities. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2016, 22, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaisoorya, T.S.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Srinath, S. The Relationship of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder to Putative Spectrum Disorders: Results from an Indian Study. Compr. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Pinto, A.; Gunnip, M.; Mancebo, M.C.; Eisen, J.L.; Rasmussen, S.A. Sexual Obsessions and Clinical Correlates in Adults with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Stein, D.J.; Chiu, W.T.; Kessler, R.C. The Epidemiology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tükel, R.; Polat, A.; Genç, A.; Bozkurt, O.; Atli, H. Gender-Related Differences among Turkish Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reale, C.; Invernizzi, F.; Panteghini, C.; Garavaglia, B. Genetics, Sex, and Gender. J. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 101, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labad, J.; Menchon, J.M.; Alonso, P.; Segalas, C.; Jimenez, S.; Jaurrieta, N.; Leckman, J.F.; Vallejo, J. Gender Differences in Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Dimensions. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mathis, M.A.; de Alvarenga, P.; Funaro, G.; Torresan, R.C.; Moraes, I.; Torres, A.R.; Zilberman, M.L.; Hounie, A.G. Gender Differences in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Literature Review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2011, 33, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denys, D.; De Geus, F.; Van Megen, H.J.G.M.; Westenberg, H.G.M. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Factor Analysis on a Clinician-Rated Scale and a Self-Report Measure. Psychopathology 2004, 37, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenman, M.; Peris, T.; Bergman, R.L.; Chang, S.; O’Neill, J.; McCracken, J.T.; Piacentini, J. Distinguishing Fear Versus Distress Symptomatology in Pediatric OCD. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Casu, G.; Carlini, M.; Conversano, C.; Gremigni, P.; Carmassi, C. Sexual Obsessions and Suicidal Behaviors in Patients with Mood Disorders, Panic Disorder and Schizophrenia. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, R.C.; de Abreu Ramos-Cerqueira, A.T.; de Mathis, M.A.; Diniz, J.B.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Miguel, E.C.; Torres, A.R. Sex Differences in the Phenotypic Expression of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Exploratory Study from Brazil. Compr. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, A.V.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Viswanath, B.; Guru, N.; George, C.M.; Bada Math, S.; Kandavel, T.; Janardhan Reddy, Y.C. Gender Differences in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Findings from a Large Indian Sample. Asian J. Psychiatry 2014, 9, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Nakatani, E.; Micali, N.; Heyman, I. Structure of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in Pediatric OCD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, P.G.; Cesar, R.C.; Leckman, J.F.; Moriyama, T.S.; Torres, A.R.; Bloch, M.H.; Coughlin, C.G.; Hoexter, M.Q.; Manfro, G.G.; Polanczyk, G.V.; et al. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Dimensions in a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Sample of School-Aged Children. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 62, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachander, S.; Meier, S.; Matthiesen, M.; Ali, F.; Kannampuzha, A.J.; Bhattacharya, M.; Kumar Nadella, R.; Sreeraj, V.S.; Ithal, D.; Holla, B.; et al. Are There Familial Patterns of Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 651196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.O.; Saraiva, L.C.; Ramos, V.R.; Oliveira, M.C.; Costa, D.L.C.; Fernandez, T.V.; Crowley, J.J.; Storch, E.A.; Shavitt, R.G.; Miguel, E.C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Probands with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder from Simplex and Multiplex Families. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 331, 115627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, B.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Cherian, A.V.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Math, S.B. Is Familial Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Different from Sporadic Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? A Comparison of Clinical Characteristics, Comorbidity and Treatment Response. Psychopathology 2011, 44, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenezloi, E.; Lakatos, K.; Horvath, E.Z.; Sasvari-Szekely, M.; Nemoda, Z. A Pilot Study of Early Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Symptom Dimensions and Association Analysis with Polymorphisms of the Serotonin Transporter Gene. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany-Navarro, M.; Cruz, R.; Real, E.; Segalàs, C.; Bertolín, S.; Rabionet, R.; Carracedo, Á.; Menchón, J.M.; Alonso, P. Looking into the Genetic Bases of OCD Dimensions: A Pilot Genome-Wide Association Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Menchon, J.M.; Pifarre, J.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Torres, L.; Salgado, P.; Vallejo, J. Long-Term Follow-up and Predictors of Clinical Outcome in Obsessive-Compulsive Patients Treated with Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Behavioral Therapy. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Daraeian, A.; Rahmani, B.; Kargari, A.; Ahmadiani, A.; Shams, J. Exploring Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Symptom Structure in Iranian OCD Patients Using Item-Based Factor Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, R.; Erbay, L.G. Relationship between Childhood Trauma and Suicide Probability in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besiroglu, L.; Uguz, F.; Ozbebit, O.; Guler, O.; Cilli, A.S.; Askin, R. Longitudinal Assessment of Symptom and Subtype Categories in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2007, 24, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelebi, F.; Koyuncu, A.; Ertekin, E.; Alyanak, B.; Tükel, R. The Features of Comorbidity of Childhood ADHD in Patients With Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervin, M.; do Rosário, M.C.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Batistuzzo, M.C.; Torres, A.R.; Damiano, R.F.; Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Miguel, E.C.; Mataix-Cols, D. Taboo Obsessions and Their Association with Suicidality in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 154, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.W.; Williams, M.T. Association Splitting of the Sexual Orientation-OCD-Relevant Semantic Network. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifter, A.; Erdogdu, A. Are the Symptom Dimensions a Predictor of Short-Term Response to Pharmacotherapy in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Indian J. Psychiatry 2022, 64, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição Costa, D.L.; Chagas Assunção, M.; Arzeno Ferrão, Y.; Archetti Conrado, L.; Hajaj Gonzalez, C.; Franklin Fontenelle, L.; Fossaluza, V.; Constantino Miguel, E.; Rodrigues Torres, A.; Gedanke Shavitt, R. Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denys, D.; De Geus, F.; Van Megen, H.J.G.M.; Westenberg, H.G.M. Use of Factor Analysis to Detect Potential Phenotypes in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 128, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragian, S.; Pashinian, A.; Fuchs, C.; Poyurovsky, M. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Dimensions in Schizophrenia Patients with Comorbid Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, L.J.; Lavell, C.; Baras, E.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Waters, A.M. Clinical Expression and Treatment Response among Children with Comorbid Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrão, Y.A.; Radins, R.B.; Ferrão, J.V.B. Psychopathological Intersection between Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Scoping Review of Similarities and Differences. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2023, 45, e20210370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Hazari, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Avasthi, A. Relationship of Obsessive Compulsive Symptoms/Disorder with Clozapine: A Retrospective Study from a Multispeciality Tertiary Care Centre. Asian J. Psychiatry 2015, 15, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Dua, D.; Chakrabarti, S.; Avasthi, A. Factor Analysis of Y-BOCS Checklist and Severity Scale among Patients with Schizophrenia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanpour, H.; Meibodi, R.G.; Navi, K.; Asadi, S. Novel Ensemble Method for the Prediction of Response to Fluvoxamine Treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Wallace, K.; Yang, E.; Roper, L.; Aryal, G.; Lee, D.; Lodhi, R.J.; Arnau, R.; Isenberg, R.; Green, B.; et al. Logistic Regression With Machine Learning Sheds Light on the Problematic Sexual Behavior Phenotype. J. Addict. Med. 2023, 17, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.J. Relationship between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Symptom Dimensions in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerberg, H.; Lochner, C.; Cath, D.C.; De Jonge, P.; Bochdanovits, Z.; Moolman-Smook, J.C.; Hemmings, S.M.J.; Carey, P.D.; Stein, D.J.; Sondervan, D.; et al. The Role of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Val66met Variant in the Phenotypic Expression of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009, 150, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, H.; Fullana, M.A.; Russell, A.J.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Nakatani, E.; Heyman, I. Obsessions and Compulsions in Children with Asperger’s Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism: A Case-Control Study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, G.; Albert, U.; Pessina, E.; Bogetto, F. Bipolar Obsessive-compulsive Disorder and Personality Disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2007, 9, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.C.; Diniz, J.B.; Fossaluza, V.; Torres, A.R.; Fontenelle, L.F.; De Mathis, A.S.; da Conceição Rosário, M.; Miguel, E.C.; Shavitt, R.G. Clinical Correlates of Social Adjustment in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selles, R.R.; Storch, E.A.; Lewin, A.B. Variations in Symptom Prevalence and Clinical Correlates in Younger Versus Older Youth with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2014, 45, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.N.; Suleman, M.; Ahmed, M.A.; Riaz, A.; Fatima, K. Identifying the Symptom Severity in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder for Classification and Prediction: An Artificial Neural Network Approach. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 2020, 2678718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, E.; Sundar, A.S.; Thennarasu, K.; Reddy, Y.C.J. Is Late-Onset OCD a Distinct Phenotype? Findings from a Comparative Analysis of Age at Onset Groups. CNS Spectr. 2014, 20, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siev, J.; Steketee, G.; Fama, J.M.; Wilhelm, S. Cognitive and Clinical Characteristics of Sexual and Religious Obsessions. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2011, 25, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Andersen, E.W.; Overo, K.F. Response of Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder to Treatment with Citalopram or Placebo. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2007, 29, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Rosario, M.C.; Brown, T.A.; Carter, A.S.; Leckman, J.F.; Sukhodolsky, D.; Katsovitch, L.; King, R.; Geller, D.; Pauls, D.L. Principal Components Analysis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms in Children and Adolescents. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Rosario, M.C.; Baer, L.; Carter, A.S.; Brown, T.A.; Scharf, J.M.; Illmann, C.; Leckman, J.F.; Sukhodolsky, D.; Katsovich, L.; et al. Four-Factor Structure of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch, E.A.; Stigge-Kaufman, D.; Marien, W.E.; Sajid, M.; Jacob, M.L.; Geffken, G.R.; Goodman, W.K.; Murphy, T.K. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Youth with and without a Chronic Tic Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.R.; Ramos-Cerqueira, A.T.A.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Do Rosário, M.C.; Miguel, E.C. Suicidality in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence and Relation to Symptom Dimensions and Comorbid Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.R.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Shavitt, R.G.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Do Rosário, M.C.; Storch, E.A.; Miguel, E.C. Comorbidity Variation in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder According to Symptom Dimensions: Results from a Large Multicentre Clinical Sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvalingam, S.; Crone, C.; Street, S.; Oar, E.L.; Gilchrist, P.; Norberg, M.M. The Causes and Consequences of Shame in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 151, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cui, D.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Q.; Xu, H.; Qiu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, K.; Xiao, Z. Cross-Sectional Comparison of the Clinical Characteristics of Adults with Early-Onset and Late-Onset Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Mugno, B.; Franklin, M.; Faber, S. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Phenomenology and Treatment Outcomes with Exposure and Ritual Prevention. Psychopathology 2013, 46, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.S.; Rozenman, M.; Peris, T.S.; O’Neill, J.; Bergman, R.L.; Chang, S.; Piacentini, J. Comparing OCD-Affected Youth with and without Religious Symptoms: Clinical Profiles and Treatment Response. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 86, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Farris, S.G. Sexual Orientation Obsessions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence and Correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 187, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Viswanath, B.; Veshnal Cherian, A.; Bada Math, S.; Kandavel, T.; Janardhan Reddy, Y.C. Impact of Age of Onset of Illness on Clinical Phenotype in OCD. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.M.; Torres, A.R.; Albertella, L.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Tiego, J.; Shavitt, R.G.; Conceição do Rosario, M.; Miguel, E.C.; Fontenelle, L.F. The Speed of Progression towards Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butwicka, A.; Gmitrowicz, A. Symptom Clusters in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): Influence of Age and Age of Onset. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 19, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.R.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Ferrão, Y.A.; do Rosário, M.C.; Torresan, R.C.; Miguel, E.C.; Shavitt, R.G. Clinical Features of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with Hoarding Symptoms: A Multicenter Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, D.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, C.H. Alexithymia in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Correlates and Symptom Dimensions. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 199, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, D.A.; Biederman, J.; Faraone, S.; Agranat, A.; Cradock, K.; Hagermoser, L.; Kim, G.; Frazier, J.; Coffey, B.J. Developmental Aspects of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Findings in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufer, M.; Grothusen, A.; Maß, R.; Peter, H.; Hand, I. Temporal Stability of Symptom Dimensions in Adult Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 88, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarden, H.; Renshaw, K.D. Shame in the Obsessive Compulsive Related Disorders: A Conceptual Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 171, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellozo, A.P.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Torresan, R.C.; Shavitt, R.G.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Rosário, M.C.; Miguel, E.C.; Torres, A.R. Symmetry Dimension in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence, Severity and Clinical Correlates. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, E.A.; Bussing, R.; Jacob, M.L.; Nadeau, J.M.; Crawford, E.; Mutch, P.J.; Mason, D.; Lewin, A.B.; Murphy, T.K. Frequency and Correlates of Suicidal Ideation in Pediatric Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2014, 46, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, V.; Kamali, Z.; Jamaati Ardakani, R.; Samimi Ardestani, M. The Relation of Childhood Trauma to Suicide Ideation in Patients Suffering from Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with Lifetime Suicide Attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 255, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velloso, P.; Piccinato, C.; Ferrão, Y.; Aliende Perin, E.; Cesar, R.; Fontenelle, L.; Hounie, A.G.; do Rosário, M.C. The Suicidality Continuum in a Large Sample of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Patients. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, G.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Rijsdijk, F.; Rück, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Lundström, S.; Larsson, H.; Eley, T.C.; Fernández de la Cruz, L. Concurrent and Prospective Associations of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms with Suicidality in Young Adults: A Genetically-Informative Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, K.M.; Woody, S.R. Appraisals of Obsessional Thoughts in Normal Samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.W.; Wetterneck, C.T.; Williams, M.T.; Chase, T. Sexual Trauma, Cognitive Appraisals, and Sexual Intrusive Thoughts and Their Subtypes: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2907–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.Z.; Warman, D.M. Appraisals of and Recommendations for Managing Intrusive Thoughts: An Empirical Investigation. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, G.; Derby, D.; Szepsenwol, O.; Nahaloni, E.; Moulding, R. Relationship Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Interference, Symptoms, and Maladaptive Beliefs. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahmelikoglu Onur, O.; Tabo, A.; Aydin, E.; Tuna, O.; Maner, A.F.; Yildirim, E.A.; Çarpar, E. Relationship between Impulsivity and Obsession Types in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2016, 20, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacentino, D.; Pasquini, M.; Tarsitani, L.; Berardelli, I.; Roselli, V.; Maraone, A.; Biondi, M. The Association of Anger with Symptom Subtypes in Severe Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Outpatients. Psychopathology 2016, 49, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakoulias, V.; Starcevic, V.; Berle, D.; Milicevic, D.; Moses, K.; Hannan, A.; Sammut, P.; Martin, A. The Characteristics of Unacceptable/Taboo Thoughts in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.M.; Menchón, J.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Pifarré, J.; Urretavizcaya, M.; Crespo, J.M.; Jiménez, S.; Vallejo, G.; Vallejo, J. Perceived Parental Rearing Style in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Relation to Symptom Dimensions. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 127, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.B.; Leonard, H.L. Sexual Obsessions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neziroglu, F.; Khemlani-Patel, S.; Yaryura-Tobias, J.A. Rates of Abuse in Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Body Image 2006, 3, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.A.; Kaur, N.; Stein, M.B. Childhood Trauma and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badour, C.L.; Tipsword, J.M.; Jones, A.C.; McCann, J.P.; Fenlon, E.E.; Brake, C.A.; Alvarran, S.; Hood, C.O.; Adams, T.G. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms and Daily Experiences of Posttraumatic Stress and Mental Contamination Following Sexual Trauma. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2023, 36, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, B.J.; Pujol, J.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Hernández-Ribas, R.; López-Solà, M.; Ortiz, H.; Alonso, P.; Deus, J.; Menchon, J.M.; Real, E.; et al. Neural Correlates of Moral Sensitivity in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsen, A.L.; Kvale, G.; Hansen, B.; van den Heuvel, O.A. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder as Predictors of Neurobiology and Treatment Response. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2018, 5, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via, E.; Cardoner, N.; Pujol, J.; Alonso, P.; López-Solà, M.; Real, E.; Contreras-Rodríguez, O.; Deus, J.; Segalàs, C.; Menchón, J.M.; et al. Amygdala Activation and Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumantanou, L.; Kasvikis, Y.; Giaglis, G.; Skapinakis, P.; Mavreas, V. Differentiation of 2 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Subgroups with Regard to Demographic and Phenomenological Characteristics Combining Multiple Correspondence and Latent Class Analysis. Psychopathology 2021, 54, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, L. Factor Analysis of Symptom Subtypes of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Their Relation to Personality and Tic Disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, M.H.; McGuire, J.; Landeros-Weisenberger, A.; Leckman, J.F.; Pittenger, C. Meta-Analysis of the Dose-Response Relationship of SSRI in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Eisen, J.L.; Mancebo, M.C.; Greenberg, B.D.; Stout, R.L.; Rasmussen, S.A. Taboo Thoughts and Doubt/Checking: A Refinement of the Factor Structure for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 151, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, M.H.; Landeros-Weisenberger, A.; Rosario, M.C.; Pittenger, C.; Leckman, J.F. Meta-Analysis of the Symptom Structure of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Millepiedi, S.; Mucci, M.; Bertini, N.; Milantoni, L.; Arcangeli, F. A Naturalistic Study of Referred Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feusner, J.D.; Mohideen, R.; Smith, S.; Patanam, I.; Vaitla, A.; Lam, C.; Massi, M.; Leow, A. Semantic Linkages of Obsessions from an International Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Mobile App Data Set: Big Data Analytics Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantouche, E.G.; Angst, J.; Demonfaucon, C.; Perugi, G.; Lancrenon, S.; Akiskal, H.S. Cyclothymic OCD: A Distinct Form? J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leckman, J.; Grice, D.; Boardman, J.; Zhang, H.; Vitale, A.; Bondi, C.; Alsobrook, J.; Peterson, B.; Cohen, D.; Rasmussen, S.; et al. Symptoms of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Rauch, S.L.; Manzo, P.A.; Jenike, M.A.; Baer, L. Use of Factor-Analyzed Symptom Dimensions to Predict Outcome With Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Placebo in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tek, C.; Kucukgoncu, S.; Guloksuz, S.; Woods, S.W.; Srihari, V.H.; Annamalai, A. Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain in First-Episode Psychosis Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Differential Effects of Antipsychotic Medications. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2016, 10, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girishchandra, B.G.; Khanna, S. Phenomenology of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Factor Analytic Approach. Indian J. Psychiatry 2001, 43, 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Marks, I.M.; Greist, J.H.; Kobak, K.A.; Baer, L. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Dimensions as Predictors of Compliance with and Response to Behaviour Therapy: Results from a Controlled Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2002, 71, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, M.C.; Di Bella, D.; Siliprandi, F.; Malchiodi, F.; Bellodi, L. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Obsessive-compulsive Patients and Association with 5-HTTLPR Polymorphism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 114, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, R.; Bille, A.; Betancur, C.; Mathieu, F.; Chabane, N.; Mouren-Simeoni, M.C.; Leboyer, M. Exploratory Analysis of Obsessive Compulsive Symptom Dimensions in Children and Adolescents: A Prospective Follow-up Study. BMC Psychiatry 2006, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, D.; Piacentini, J.; Greisberg, S.; Graae, F.; Jaffer, M.; Miller, J. The Structure of Childhood Obsessions and Compulsions: Dimensions in an Outpatient Sample. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Brown, C.H.; Riddle, M.A.; Grados, M.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Hoehn-Saric, R.; Shugart, Y.Y.; Liang, K.-Y.; Samuels, J.; Nestadt, G. Factor Analysis of the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale in a Family Study of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2007, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højgaard, D.R.M.A.; Mortensen, E.L.; Ivarsson, T.; Hybel, K.; Skarphedinsson, G.; Nissen, J.B.; Valderhaug, R.; Dahl, K.; Weidle, B.; Torp, N.C.; et al. Structure and Clinical Correlates of Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms in a Large Sample of Children and Adolescents: A Factor Analytic Study across Five Nations. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.P.; Samuels, J.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Cannistraro, P.; Grados, M.; Riddle, M.A.; Liang, K.-Y.; Cullen, B.; Hoehn-Saric, R.; Nestadt, G. Clinical Correlates of Recurrent Major Depression in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2004, 20, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prisco, M.; Tapoi, C.; Oliva, V.; Possidente, C.; Strumila, R.; Takami Lageborn, C.; Bracco, L.; Girone, N.; Macellaro, M.; Vieta, E.; et al. Clinical Features in Co-Occuring Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 80, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Millepiedi, S.; Perugi, G.; Pfanner, C.; Berloffa, S.; Pari, C.; Mucci, M.; Akiskal, H.S. A Naturalistic Exploratory Study of the Impact of Demographic, Phenotypic and Comorbid Features in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychopathology 2010, 43, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mathis, M.A.; Diniz, J.B.; Hounie, A.G.; Shavitt, R.G.; Fossaluza, V.; Ferrão, Y.; Leckman, J.F.; de Bragança Pereira, C.; do Rosario, M.C.; Miguel, E.C. Trajectory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Comorbidities. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alvarenga, P.G.; de Mathis, M.A.; Alves, A.C.D.; do Rosário, M.C.; Fossaluza, V.; Hounie, A.G.; Miguel, E.C.; RodriguesTorres, A. Clinical Features of Tic-Related Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Results from a Large Multicenter Study. CNS Spectr. 2012, 17, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, Y.; Matsuda, N.; Nonaka, M.; Fujio, M.; Kuwabara, H.; Kono, T. Sensory Phenomena Related to Tics, Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms, and Global Functioning in Tourette Syndrome. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mula, M.; Cavanna, A.E.; Critchley, H.; Robertson, M.M.; Monaco, F. Phenomenology of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Patients with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy or Tourette Syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 20, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melli, G.; Moulding, R.; Gelli, S.; Chiorri, C.; Pinto, A. Assessing Sexual Orientation–Related Obsessions and Compulsions in Italian Heterosexual Individuals: Development and Validation of the Sexual Orientation Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (SO-OCS). Behav. Ther. 2016, 47, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazier, K.; Calixte, R.M.; Rothschild, R.; Pinto, A. High Rates of OCD Symptom Misidentification by Mental Health Professionals. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, N. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Commonly Missed Diagnosis in Primary Care. Prim. Psychiatry 2003, 10, c14. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.T.; Wetterneck, C.; Tellawi, G.; Duque, G. Domains of Distress Among People with Sexual Orientation Obsessions. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.M.; Twohig, M.P. Sexual Orientation Intrusive Thoughts and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2023, 37, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman, R.; Leibovits, G.; Halfon, C.N.; Schonbach, M.; Doron, G. Interpersonal Transmission of ROCD Symptoms and Susceptibility to Infidelity in Romantic Relationships. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2023, 37, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.I.; Limon, D.L.; Candelari, A.E.; Cepeda, S.L.; Ramirez, A.C.; Guzick, A.G.; Kook, M.; La Buissonniere Ariza, V.; Schneider, S.C.; Goodman, W.K.; et al. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Misdiagnosis among Mental Healthcare Providers in Latin America. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2022, 32, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.S.; Wetterneck, C.T. OCD Taboo Thoughts and Stigmatizing Attitudes in Clinicians. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durna, G.; Yorulmaz, O.; Aktaç, A. Public Stigma of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Schizophrenic Disorder: Is There Really Any Difference? Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinciotti, C.M.; Smith, Z.; Singh, S.; Wetterneck, C.T.; Williams, M.T. Call to Action: Recommendations for Justice-Based Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder With Sexual Orientation and Gender Themes. Behav. Ther. 2022, 53, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health; Excellence, C. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Treatment. Clinical Guideline [CG31]. 2005. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Ferrão, Y.A.; Shavitt, R.G.; Bedin, N.R.; de Mathis, M.E.; Carlos Lopes, A.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Torres, A.R.; Miguel, E.C. Clinical Features Associated to Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 94, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeros-Weisenberger, A.; Bloch, M.H.; Kelmendi, B.; Wegner, R.; Nudel, J.; Dombrowski, P.; Pittenger, C.; Krystal, J.H.; Goodman, W.K.; Leckman, J.F.; et al. Dimensional Predictors of Response to SRI Pharmacotherapy in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 121, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetti, C.N.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Kandavel, T.; Kashyap, K.; Singisetti, S.; Hiremath, A.S.; Siddequehusen, M.U.F.; Raghunandanan, S. Clinical Predictors of Drug Nonresponse in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Brakoulias, V. Symptom Subtypes of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Are They Relevant for Treatment? Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2008, 42, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Cuadras, D.; Gabriëls, L.; Denys, D.; Goodman, W.; Greenberg, B.D.; Jimenez-Ponce, F.; Kuhn, J.; Lenartz, D.; Mallet, L.; et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Treatment Outcome and Predictors of Response. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiong, B.; Li, D.; Wen, R.; et al. The Suitability of Different Subtypes and Dimensions of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder for Treatment with Anterior Capsulotomy: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 2020, 97, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højgaard, D.R.M.A.; Hybel, K.A.; Mortensen, E.L.; Ivarsson, T.; Nissen, J.B.; Weidle, B.; Melin, K.; Torp, N.C.; Dahl, K.; Valderhaug, R.; et al. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Dimensions: Association with Comorbidity Profiles and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Outcome in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezahler, A.; Kuckertz, J.M.; Schreck, M.; Narine, K.; Dattolico, D.; Falkenstein, M.J. Examination of Outcomes among Sexual Minorities in Treatment for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2022, 33, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olino, T.M.; Gillo, S.; Rowe, D.; Palermo, S.; Nuhfer, E.C.; Birmaher, B.; Gilbert, A.R. Evidence for Successful Implementation of Exposure and Response Prevention in a Naturalistic Group Format for Pediatric OCD. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steketee, G.; Siev, J.; Fama, J.M.; Keshaviah, A.; Chosak, A.; Wilhelm, S. Predictors of Treatment Outcome in Modular Cognitive Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetnejad, Z.; Assarian, F.; Omidi, A.; Najarzadegan, M.R. Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Fluoxetine on Sexual Function of Women with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 3156–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Werkle, N.; Cludius, B.; Jelinek, L.; Moritz, S.; Westermann, S. Unguided Internet-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelles, C.; Bulnes, L.C. EMDR as Treatment Option for Conditions Other Than PTSD: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Soriano, G.; Belloch, A. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Differences in Distress, Interference, Appraisals and Neutralizing Strategies. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2013, 44, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S.L.; Ching, T.H.W.; Williams, M.T. Pedophilia-Themed Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Assessment, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment with Exposure and Response Prevention. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Elstein, J.; Buckner, E.; Abelson, J.M.; Himle, J.A. Symptom Dimensions in Two Samples of African Americans with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Obs. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2012, 1, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, J.F.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Pinto, A.; Murphy, D.L.; Piacentini, J.; Rauch, S.L.; Fyer, A.J.; Grados, M.A.; Greenberg, B.D.; Knowles, J.A.; et al. Sex-Specific Clinical Correlates of Hoarding in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufer, M.; Fricke, S.; Moritz, S.; Kloss, M.; Hand, I. Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prediction of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Outcome. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 113, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alarcón, R.; de la Iglesia, J.I.; Casado, N.M.; Montejo, A.L. Online Porn Addiction: What We Know and What We Don’t—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E. Assessment and Treatment of Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Minn. Med. 2003, 86, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma, J.M.; Black, D.W. Compulsive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2004, 6, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draps, M.; Kowalczyk-Grębska, N.; Marchewka, A.; Shi, F.; Gola, M. White Matter Microstructural and Compulsive Sexual Behaviors Disorder—Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, C.H.N.; Hounie, A.; De Tubino Scanavino, M.; Miguel, E.C. OCD and Transvestism: Is There a Relationship? Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001, 103, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Potenza, M.N.; Jiménez-Murcia, S. Obsessive-Compulsive, Harm-Avoidance and Persistence Tendencies in Patients with Gambling, Gaming, Compulsive Sexual Behavior and Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorders/Concerns. Addict. Behav. 2023, 139, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, J.; Briken, P.; Stein, D.J.; Lochner, C. Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence and Associated Comorbidity. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaychuk, L.A.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Miguel, E.C.; de Mathis, M.A.; Scanavino, M.D.T.; Kim, H.S. Co-Occurring Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and Compulsive Sexual Behavior: Clinical Features and Psychiatric Comorbidities. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 4111–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakoulias, V.; Starcevic, V.; Albert, U.; Arumugham, S.S.; Bailey, B.E.; Belloch, A.; Borda, T.; Dell’Osso, L.; Elias, J.A.; Falkenstein, M.J.; et al. The Rates of Co-Occurring Behavioural Addictions in Treatment-Seeking Individuals with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Preliminary Report. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2020, 24, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewska, E.; Gola, M.; Kraus, S.W.; Lew-Starowicz, M. Spotlight on Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder: A Systematic Review of Research on Women. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2025–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, H.-J.; Montag, C. Where to Put Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD)? Phenomenology Matters. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil, A.F.; de Mathis, M.A.; Torresan, R.C.; Diniz, J.B.; Alvarenga, P.; do Rosário, M.C.; Cordioli, A.V.; Torres, A.R.; Miguel, E.C. Alcohol Use Disorders in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The Importance of Appropriate Dual-Diagnosis. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2009, 100, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos, C.N.; Kim, H.S.; Requião, M.G.; Marasaldi, R.F.; Filomensky, T.Z.; Hodgins, D.C.; Tavares, H. Gender Differences in Compulsive Buying Disorder: Assessment of Demographic and Psychiatric Co-Morbidities. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant Weinandy, J.T.; Lee, B.; Hoagland, K.C.; Grubbs, J.B.; Bőthe, B. Anxiety and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Sex. Res. 2023, 60, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Lochner, C.; Stein, D.J.; Goudriaan, A.E.; van Holst, R.J.; Zohar, J.; Grant, J.E. Behavioural Addiction-A Rising Tide? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holas, P.; Draps, M.; Kowalewska, E.; Lewczuk, K.; Gola, M. A Pilot Study of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Measure: Value | Association (Measured Value) | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associations with the Sexual Inhibition due to threat of performance failure (SIS1) subscale | |||

| Both | OBQ-46: Perfectionism | βANCOVA = −0.013, t = −2.41 * | Pozza (2021) [33] |

| DPSS-R: DS X contamination/washing symptoms | βGLM (CI95 −0.069 −0.118 −0.021) χ2: 7.807 df = 1 * | Pozza, (2020) [36] | |

| SIS 2 | r: 0.47 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| DPSS-r-DP | r: 0.29 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| DPSS-r-DS | r: 0.36 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OBQ 46-P | r: 0.41 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OBQ 46-RH | r: 0.31 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OBQ 46-CT | r: 0.30 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OBQ 46-RO | r: 0.30 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OBQ 46-IT | r: 0.40 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| Associations with the Sexual Inhibition due to fear of consequences (SIS2) subscale | |||

| Women | ASQ-C | βGLM = −0.070 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] |

| ASQ-P | βGLM = −0.108 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender | βGLM = −3.527 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender and ASQ-R | βGLM = 0.059 *, (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender and OCIR-R-C | βGLM = 0.963 *, (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Both | OCI-R-Checking | β = −0.10, t = −2.21 * | Pozza, (2019) [32] |

| OCIR-CHECKING | β = −0.10, t = −2.21 * | Pozza, (2019) [32] | |

| DPSS-R: DS and contamination/washing symptoms | βGLM (CI95): −0.070 (−0.120 −0.020) χ2: 7.626 df = 1 * | Pozza, (2020) [36] | |

| DPSS-R-DP | r: 0.28 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| DPSS-DS | r: 0.24 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OCIR Checking | r: 0.24 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| OCIR Washing | r: 0.29 * | Pozza, (2019) [34] | |

| ASQ-NA | βGLM = 0.036 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-C | βGLM = 0.044 *, (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| OCIR-R-C | βGLM = 0.520 *, (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-C | βGLM = 0.046 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-NA | βGLM = 0.051 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Associations with the Sexual Excitement (SES) subscale | |||

| Women | ASQ-DC | βGLM = 0.051 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] |

| Gender | βGLM = −3.336 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender and ASQ-C | βGLM = −0.057 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender and ASQ-DC | βGLM = −0. 051 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Both | OCIR Washing | β = 0.12, t = 2.92 * | Pozza, (2019) [32] |

| OCI-R: Total | βANCOVA = 0.014, t = 3.03 * | Pozza, (2021) [33] | |

| OCIR total | βGLM = 0.012 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| Gender | βGLM = −3.240 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-DC | βGLM = −0.030 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-C | βGLM = −0.030 * (Gender, OCI-R-T, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| ASQ-DC | βGLM = −0.032 * (Gender, OCI-R-C, ASQ) | Dettore, (2021) [37] | |

| OCIR-R-T | r: 0.24 * | Mukhopadhyay, (2010) [38] | |

| Study | Sample | Instruments Used | Global Prevalence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Ocd | Sd | Total | Male | Female | |

| Staebler, (1993) [26] | 118 | 54 | 64 | DSM III | N/A | |||

| Monteiro & Noshirvani, (1987) [41] | 46 | 25 | 21 | N/A | N/A | 54 | 64 | 43 |

| Freund & Steketee, (1989) [4] | 44 | 19 | 25 | MOCL, CAC, DSM III | 0–9 points Likert-Scale | 39 | 25 | |

| Van Minnen, (2000) [3] | 14 | - | 14 | N/A | QSD | 76.4 | - | 76.4 |

| Vulink, (2005) [43] | 87 | - | 87 | N/A | Scale based on ASEX and CSFQ | 50 | - | 50 |

| Kendurkar et al. (2008) [44] | 50 | 28 | 22 | DSM-IV | ASEX | 50 | 28 | 22 |

| Aksoy et al. (2012) [24] | 40 | N/A | N/A | N/A | GRSSI | - | - | 24 |

| Ghassemzadeh et al. (2016) [40] | 56 | 20 | 36 | OCI-R; MOCI | FSFI, IIEF-30 | 60.7 | 25 | 81 |

| Zerdzinski et al. (2022) [30] | 175 | 82 | 93 | Y-BOCS | ASEX | 66.6 | 54.2 | 77.5 |

| Study | Infrequency | General Satisfaction | Aversion | Avoidance | Desire | Excitement | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| Staebler, (1993) [26] | 63 | |||||||||||||||||

| Monteiro & Noshirvani, (1987) [41] | 3 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 13 | 9,5 | ||||||||||||

| Freund & Steketee, (1989) [4] | 25 | 73 | ||||||||||||||||

| Van Minnen, (2000) [3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vulink, (2005) [43] | 28 | 62 | 29 | |||||||||||||||

| Kendurkar et al. (2008) [44] | 13 | 28.6 | 22.8 | 24 | 25 | 22.8 | ||||||||||||

| Aksoy et al. (2012) [24] | 57.1 | 63.6 | 24 | 60 | - | - | 60 | |||||||||||

| Ghassemzadeh et al. (2016) [40] | 44.6 | 50 | 42 | 53 | 10 | 50 | 58 | |||||||||||

| Zerdzinski et al. (2022) [30] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Study | Arousal | Penile Erection/ Vaginal Lubrication | Premature Ejaculation | Orgasm | Orgasm Satisfaction | Pain | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| Staebler, (1993) [26] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Monteiro & Noshirvani, (1987) [41] | 6 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Freund & Steketee, (1989) [4] | 2 | 9 | 9 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Van Minnen, (2000) [3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vulink, (2005) [43] | 25 | 25 | 33 | 20 | ||||||||||||||

| Kendurkar et al. (2008) [44] | 26 | 21.4 | 31.8 | 46 | 46.4 | 45.4 | 28 | 35.7 | 18.2 | |||||||||

| Aksoy et al. (2012) [24] | 70 | (>HC) | (>HC) | (>PD) | ||||||||||||||

| Ghassemzadeh et al. (2016) [40] | 30.3 | 20 | 36 | 37.5 | 25 | 44 | 40 | 53 | ||||||||||

| Zerdzinski et al. (2022) [30] | 39 | 36.8 | 41.9 | 51 | 52.6 | 51.6 | 54.8 | |||||||||||

| Authors | N | % Women | SO% | % Females | % Males | Setting | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aksaray, (2001) [45] | 46 | 100 | 4 | 4 | - | Outpatients | All-female sample |

| Alemany-Navarro, (2020) [77] | 399 | 52 | 255 | - | - | Outpatients | |

| Alonso, (2001) [78] | 40 | 50 | 20 | - | - | Outpatients | |

| Asadi, (2016) [79] | 236 | 61 | 16.20 | - | - | Outpatients | |

| Ay, (2018) [80] | 67 | 52 | 16 | - | - | Inpatients | 3% without childhood trauma 30% with childhood trauma |

| Besiroglu, (2007) [81] | 109 | 59 | 14.3 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Çelebi, (2020) [82] | 95 | 62.10 | 34.20 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Cervin, (2022) [83] | 500 | 55.80 | 1.90 | - | - | Outpatients | “taboo obsessions” |

| Cherian, (2014) [70] | 545 | 39 | 50.10 | 14.10 | 36.10 | Outpatients | |

| Ching, (2017) [84] | 120 | 68 | 39.66 | - | - | Outpatients | College students Sexual orientation |

| Ching, (2021) [54] | 592 | 69 | 18.80 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Cifter, (2022) [85] | 102 | 57.80 | 59.80 | - | - | Outpatients | Children Harm/sexual |

| Cordeiro, (2015) [7] | 75 | 16 | 5.01 | - | - | Inpatients | - |

| Costa, (2012) [86] | 901 | - | 55.40 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Denys, (2004) [87] | 335 | 62 | 5.90 | - | - | Outpatients | Aggressive, sexual, and religious |

| Doron, (2014) [48] | 157 | 45 | 12.50 | - | - | Outpatients | Partner and sexual symptoms in OCD |

| Faragian, (2009) [88] | 83 | 24.50 | 22 | - | - | Inpatients | |

| Farrell, (2020) [89] | 40 | 50 | 10 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Ferrão, (2023) [90] | 49 | 58 | 38.1 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Freund, (1989) [4] | 44 | 55 | 36 | - | Outpatients | - | |

| Grover, (2015) [91] | 220 | 54 | 31 | - | - | Inpatients | - |

| Grover, (2017) [92] | 181 | 46.40 | 19.54 | - | - | Outpatients | Patients with schizophrenia; aggressive, sexual, and religious obsessions; and counting items |

| Hasanpour, (2018) [93] | 151 | 68 | 23 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Hasler, (2005) [9] | 317 | 58.20 | 76 | outpatients | |||

| Jiang, (2023) [94] | 120 | 232 | 33.30 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Kenezloi, (2018) [76] | 102 | 30.40 | 7.70 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Kim, (2014) [95] | 57 | 33 | 33 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Kuty-Pachecka, (2021) [52] | 313 | - | 16.80 | 50 | 65 | Outpatients | Meta-analysis |

| Labad, (2008) [64] | 193 | 38 | 22,6 | 5.60 | 23.70 | Outpatients | Sexual/religious |

| Lochner, (2009) [96] | 606 | 52.30 | 70 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Mack, (2010) [97] | 318 | 50 | 18.30 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Maina G, (2007) [98] | 204 | 50 | 22.10 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Mataix- Cols, (2008) [71] | 238 | 36.80 | 28 | 18.40 | 33.60 | ||

| Mathis, (2011) [65] | 215 | 47 | 88 | Cluster including aggressive, sexual, religious, somatic obsessions, and checking compulsions | |||

| Monzani, (2015) [55] | 189 | 45.50 | 63 | - | - | Outpatients | Forbidden thoughts |

| Rosa, (2012) [99] | 815 | 58.30 | 4.18 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Selles, (2014) [100] | 292 | 7.1 16.60 | - | - | Outpatients | Younger youth Older youth | |

| Shahzad, (2020) [101] | 200 | 55.50 | 50.50 | - | - | Inpatients | - |

| Sharma, (2014) [102] | 802 | 38 | 28.80 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Siev, (2011) [103] | 15 | 53 | 39 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Stein, (2007) [104] | 434 | 54 | 18.70 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Stewart, (2007) [105] | 231 | 67 | 16.10 | - | - | Outpatients | |

| Stewart, (2008) [106] | 83 | 24.50 | 22 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Storch, (2008) [107] | 74 | 29 | 6.06 | - | - | Outpatients | Children |

| Torres, (2011) [108] | 582 | 56.4 | 51.40 | - | - | Outpatients | Sexual/religious |

| Torres, (2016) [109] | 1001 | 56.80 | 57.10 | - | - | Outpatients | Sexual/religious |

| Torresan (2013) [10] | 858 | 58.70 | 55.70 | 52.20 | 60.70 | Outpatients | |

| Torresan et al. (2009) [69] | 330 | 45 | 33.60 | 27.39 | 39.27 | Outpatients | - |

| Visvalingam, (2022) [110] | 53 | 74.50 | 7.27 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Viswanath, (2011) [75] | 84 80 | - | 14.3 30.0 | - | - | Outpatients | Familial OCD Sporadic OCD |

| 164 | - | 14 | - | - | Total | ||

| Wang, (2012) [111] | 275 327 | 33.10 52.60 | 29.80 18 | - | - | Outpatients | Early-onset OCD Late-onset OCD |

| Williams, (2013) [112] | 83 | 56.80 | 12.20 | - | - | Outpatients | - |

| Wu, (2018) [113] | 215 | 43 | 92 76 | - | - | Outpatients | Symptoms of severity No symptoms of severity “aggressive, sexual, somatic, and checking” |

| Author | Year | Number of OCD Patients (n) | Mean Age | Statistical Analysis | Total Variance Explained by the Model % | Total Number of Factors | Factor Number for Sexual Obsessions | Variance Explained by Factor | Associated Obsessive Symptoms | Associated Behavioral (Compulsive) Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baer [144] | 1994 | 107 | Adults | Varimax | 57 | 3 | 3 | 11.3 | Aggression, religious | - |

| Hantouche [150] | 2003 | 615 | Adults | Varimax | 3 | 2 | Aggressive, religious, miscellaneous | Miscellaneous | ||

| Leckman [151] | 1997 | 292 | Adults | Varimax | 63 | 4 | 1 | 30.1 | Aggressive, religious, somatic | Checking |

| Mataix-Cols [152] | 1999 | 354 | Adults | Varimax | 65 | 5 | 5 | 9.7 | Religious | - |

| Tek [153] | 2016 | 45 | Adults | Varimax | 56 | 5 | 4 | 9.7 | Religious | - |

| Girishchandra [154] | 2001 | 202 | Adults | Varimax | 35 | 5 | 5 | 4.2 | Religious | - |

| Mataix-Cols [155] | 2002 | 153 | Adults | Varimax | 64 | 5 | 5 | 7.9 | Somatic | |

| Cavallini [156] | 2002 | 180 | Adults | Varimax | 60 | 5 | 3 | 11.5 | Aggressive, somatic, religious | Checking, repeating |

| Bezahler [27] | 2024 | 160 | Adults | Varimax | 44 | 4 | 4 | 11.8 | Religious | - |

| Denys [87] | 2004 | 335 | Adults | Varimax | 41 | 5 | 2 | 9.8 | Aggressive, religious | |

| Denys, de Geus [66] | 2004 | 150 | Adults | Varimax | 42.5 | 5 | 1 | 14.5 | Aggressive, religious | |

| Hasler [9] | 2005 | 169 | Adults | Varimax | 63 | 4 | 1 | 19.5 | Aggressive, religious, somatic | Checking |

| Kim [95] | 2005 | 124 | Adults | Varimax | 62 | 4 | 3 | 10 | Aggressive | |

| Delorme [157] | 2006 | 73 | Child | Varimax | 78 | 4 | 2 | 13 | Aggressive, somatic | Counting |

| Mckay [158] | 2006 | 137 | Child | Oblimin | 68 | 4 | 3 | 12.7 | Contamination, aggressive, magical thoughts, somatic, religious, symmetry | Repeating, counting, rituals involving others |

| Pinto [146] | 2007 | 293 | Adult | Varimax | 76.4 | 5 | 5 | 7.4 | Aggressive, religious | |

| Cullen [159] | 2007 | 221 | Adult | Varimax | - | 4 | 1 | - | Aggressive, religious, somatic | |

| Hasler [9] | 2005 | 418 | Adult | Promax | 63.7 | 4 | 1 | 17.7 | Aggressive, religious, somatic | Checking |

| Stein [104] | 2007 | 434 | Adult | Varimax | - | 5 | 3 | - | Aggressive, religious | |

| Stewart [105] | 2007 | 231 | Child | Promax | 66.6 | 4 | 4 | 9.1 | Religious | |

| Mataix-Cols [71] | 2008 | 238 | Child | Varimax | 54.8 | 4 | 2 | 13.7 | Aggressive, religious | |

| Bloch [147] | 2008 | 5124 | General | Varimax, meta-analysis | 79 | 4 | 2 | 21 | Aggressive, religious, somatic | |

| 4445 | Adult | |||||||||

| 679 | Child | 81.7 | 4 | 4 | 16.4 | |||||

| Faragian [88] | 2009 | 110 | Adult | Varimax | 58.7 | 5 | 1 | 15.9 | Religious, aggressive | Counting |

| Højgaard [160] | 2017 | 854 | Child | Varimax | - | 3 | 1 | - | Aggressive | Checking |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Iglesia-Larrad, J.I.; González-Bolaños, R.K.; Peso Navarro, I.M.; de Alarcón, R.; Casado-Espada, N.M.; Montejo, Á.L. Sexuality and Related Disorders in OCD and Their Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6819. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196819

de la Iglesia-Larrad JI, González-Bolaños RK, Peso Navarro IM, de Alarcón R, Casado-Espada NM, Montejo ÁL. Sexuality and Related Disorders in OCD and Their Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6819. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196819

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Iglesia-Larrad, Javier I., Ramón Kristofer González-Bolaños, Isabel María Peso Navarro, Rubén de Alarcón, Nerea M. Casado-Espada, and Ángel L. Montejo. 2025. "Sexuality and Related Disorders in OCD and Their Symptoms" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6819. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196819

APA Stylede la Iglesia-Larrad, J. I., González-Bolaños, R. K., Peso Navarro, I. M., de Alarcón, R., Casado-Espada, N. M., & Montejo, Á. L. (2025). Sexuality and Related Disorders in OCD and Their Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6819. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196819