A Rare Case of Systemic Amyloidosis Involving the Thyroid in a Young Patient

Abstract

1. Introduction

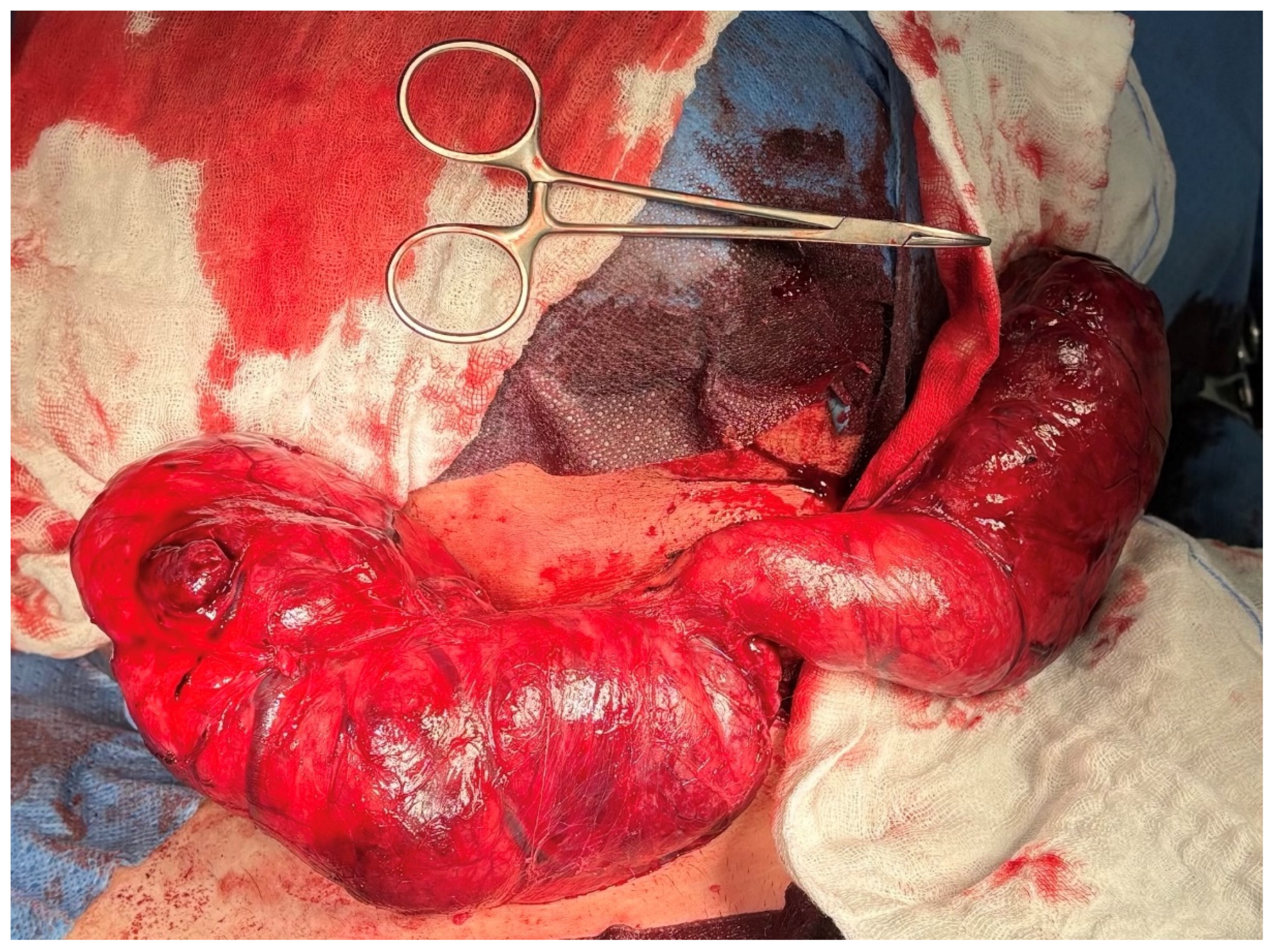

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

| Author, Year | Age/Sex | Amyloid Type | Clinical Features | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law et al., 2013 [8] | 33–85/5 pts | Secondary (AA) | Hoarseness, compressive symptoms, thyroid dysfunction | Thyroidectomy in most cases | Variable, vocal cord paralysis in one |

| Cannizzaro et al., 2018 [18] | 58/F | Primary (AL) | Goitre, systemic amyloidosis, multiple myeloma | Total thyroidectomy | Symptom relief |

| Cohan et al., 2000 [14] | 52/M | Secondary (AA) | Systemic amyloidosis secondary to ankylosing spondylitis | Total thyroidectomy | Stable |

| Pérez Fontán et al., 1992 [22] | 10/M | Secondary (AA) | Neck mass, JIA | Surgical biopsy | NR |

| Nagai et al., 1998 [20] | 25/F | Secondary (AA) | Goitre, vasculitis, thyrotoxicosis | Thyroidectomy | NR |

| Lari et al., 2020 [23] | 54/F | Secondary (AA) | Goitre, compressive symptoms | Total thyroidectomy | Stable |

| Jakubović-Čičkušić et al., 2020 [24] | 65/M | Secondary (AA) | Thyroid mass, systemic amyloidosis | Total thyroidectomy | NR |

| Gonzalez-Gil et al., 2024 [25] | 72/F | Secondary (AA) | Amyloid goitre, systemic AA | Thyroidectomy | NR |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| FNAC | Fine-needle aspiration cytology |

| AA | Amyloid A (Secondary Amyloidosis) |

| AP | Anteroposterior |

| CC | Craniocaudal |

| FNAB | Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy |

| MR | Magnetic Resonance |

| RL | Right–Left (transverse) dimension |

| USG/US | Ultrasonography |

| NR | Not reported |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| CRF | Chronic renal failure |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| AL | Amyloid light-chain |

| AH | Amyloid heavy-chain |

| Rx | Treatment |

References

- Giorgetti, A.; Pucci, A.; Aimo, A. A brief history of amyloidosis. In Cardiac Amyloidosis: Diagnosis and Treatment; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Perutz, M.F. Mutations make enzyme polymerize. Nature 1997, 385, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Nosé, V. Localized Amyloid in Thyroid: Are We Missing It? Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2013, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini, G.; Bellotti, V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.; Drozdzowska, B. 9 Diagnostyka Patomorfologiczna Nienowotworowych Chorób Tarczycy. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=pl&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=diagnostyka+patomorfologiczna+nienowotworowych+chorób+tarczycy&btnG= (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Więsik-Szewczyk, E. AA Amyloidoza—Przyczyny, diagnostyka, opcje terapeutyczne. Hematologia 2018, 9, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girnius, S.; Dember, L.; Doros, G.; Skinner, M. The changing face of AA amyloidosis: A single center experience. Amyloid 2011, 18 (Supp. S1), 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.H.; Dean, D.S.; Scheithauer, B.; Earnest F4th Sebo, T.J.; Fatourechi, V. Symptomatic amyloid goiters: Report of five cases. Thyroid 2013, 23, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.H.; Uyar, P.; Ozdemir, F.N. Diagnosing amyloid goitre with thyroid aspiration biopsy. Cytopathology 2006, 17, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, H.; Maeda, H.; Isomoto, I.; Nagatomo, H.; Nakashima, A.; Ashizawa, A. Computed tomography in amyloid goiter. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1988, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.N.; Pepys, M.B. Imaging amyloidosis with radiolabelled SAP. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, 22, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergesio, F.; Ciciani, A.M.; Manganaro, M.; Palladini, G.; Santostefano, M.; Brugnano, R.; Di Palma, A.M.; Gallo, M.; Rosati, A.; Tosi, P.L.; et al. Immunopathology Group of the Italian Society of Nephrology. Renal involvement in systemic amyloidosis: An Italian collaborative study on survival and renal outcome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, H.J.; Goodman, H.J.; Gilbertson, J.A.; Gallimore, J.R.; Sabin, C.A.; Gillmore, J.D.; Hawkins, P.N. Natural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, P.; Hirschowitz, S.; Rao, J.Y.; Tanavoli, S.; Van Herle, A.J. Amyloid goiter in a case of systemic amyloidosis secondary to ankylosing spondylitis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2000, 23, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.D.; Buxbaum, J.N.; Eisenberg, D.S.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M.J.M.; Sekijima, Y.; Sipe, J.D.; Westermark, P. Amyloid nomenclature 2020: Update and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid 2020, 27, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, H.A.; Koucky, R.F.; Eklund, C.M. Primary amyloidosis limited to tissue of mesodermal origin. Am. J. Pathol. 1935, 11, 977–988. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyńska, M.; Borucki, Ł.; Popko, M. Amyloidoza w obrębie głowy i szyi. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2008, 62, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannizzaro, M.A.; Lo Bianco, S.; Saliba, W.; D’Errico, S.; Pennetti Pennella, F.; Buttafuoco, G.; Provenzano, D.; Magro, G. A rare case of primary thyroid amyloidosis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 53, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kosowska, B.; Januszewski, A.; Tokarska, M.; Bednarek-Tupikowska, G.; Zdrojewicz, Z.; Jach, H. Amyloidozy i białka amyloidogenne. Med. Wet. 2001, 57, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, Y.; Ohta, M.; Yokoyama, H.; Takamura, T.; Kobayashi, K.I. Amyloid goiter presented as a subacute thyroiditis-like symptom in a patient with hypersensitivity vasculitis. Endocr. J. 1998, 45, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- el-Reshaid, K.; al-Tamami, M.; Johny, K.V.; Madda, J.P.; Hakim, A. Amyloidosis of the thyroid gland: Role of ultrasonography. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 1994, 22, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Fontán, F.J.; Mosquera Osés, J.; Pombo Felipe, F.; Rodriguez Sanchez, I.; Arnaiz Peña, S. Amyloid goiter in a child–US, CT and MR evaluation. Pediatr. Radiol. 1992, 22, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lari, E.; Afshan, G.; Aftab, M.; Raheem, A. Amyloid Goiter: An Unusual Cause of Thyroid Enlargement. Cureus 2020, 12, e10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubović-Čičkušić, D.; Bulić-Jakus, F.; Škrabić, V.; Glavina-Durdov, M. Amyloid goiter in a patient with systemic AA amyloidosis: A case report. Acta Clin. Croat. 2020, 59, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gil, A.; Martín-Varillas, J.L.; López-Mejías, R.; Genre, F.; Corrales, A.; Armesto, S.; Castañeda, S.; Blanco, R.; González-Gay, M.A. Secondary amyloidosis presenting as amyloid goiter: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasprzak, O.J.; Stępińska, K.; Kiedrowska, K.; Błaszkowski, T.; Kudrymska, A.; Sikora, S.; Miernik, M.; Romanowski, M. A Rare Case of Systemic Amyloidosis Involving the Thyroid in a Young Patient. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6741. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196741

Kasprzak OJ, Stępińska K, Kiedrowska K, Błaszkowski T, Kudrymska A, Sikora S, Miernik M, Romanowski M. A Rare Case of Systemic Amyloidosis Involving the Thyroid in a Young Patient. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6741. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196741

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasprzak, Oliwia Julia, Kamila Stępińska, Kaja Kiedrowska, Tomasz Błaszkowski, Aleksandra Kudrymska, Sylwia Sikora, Maciej Miernik, and Maciej Romanowski. 2025. "A Rare Case of Systemic Amyloidosis Involving the Thyroid in a Young Patient" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6741. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196741

APA StyleKasprzak, O. J., Stępińska, K., Kiedrowska, K., Błaszkowski, T., Kudrymska, A., Sikora, S., Miernik, M., & Romanowski, M. (2025). A Rare Case of Systemic Amyloidosis Involving the Thyroid in a Young Patient. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6741. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196741