Evaluation of the Sphingolipidomic Profile in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: Relationships with Parameters Related to Body Composition, Cardiovascular Function, Glucometabolic Homeostasis, and Lipoprotein Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Information

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. REE Measurement

2.5. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

2.6. Metabolic Variables

2.7. Lipid Extraction from Plasma and Sphingolipid Target Analysis by LC-MS/MS

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Biochemical, and Clinical Parameters

3.2. Sphingolipidomic Profile

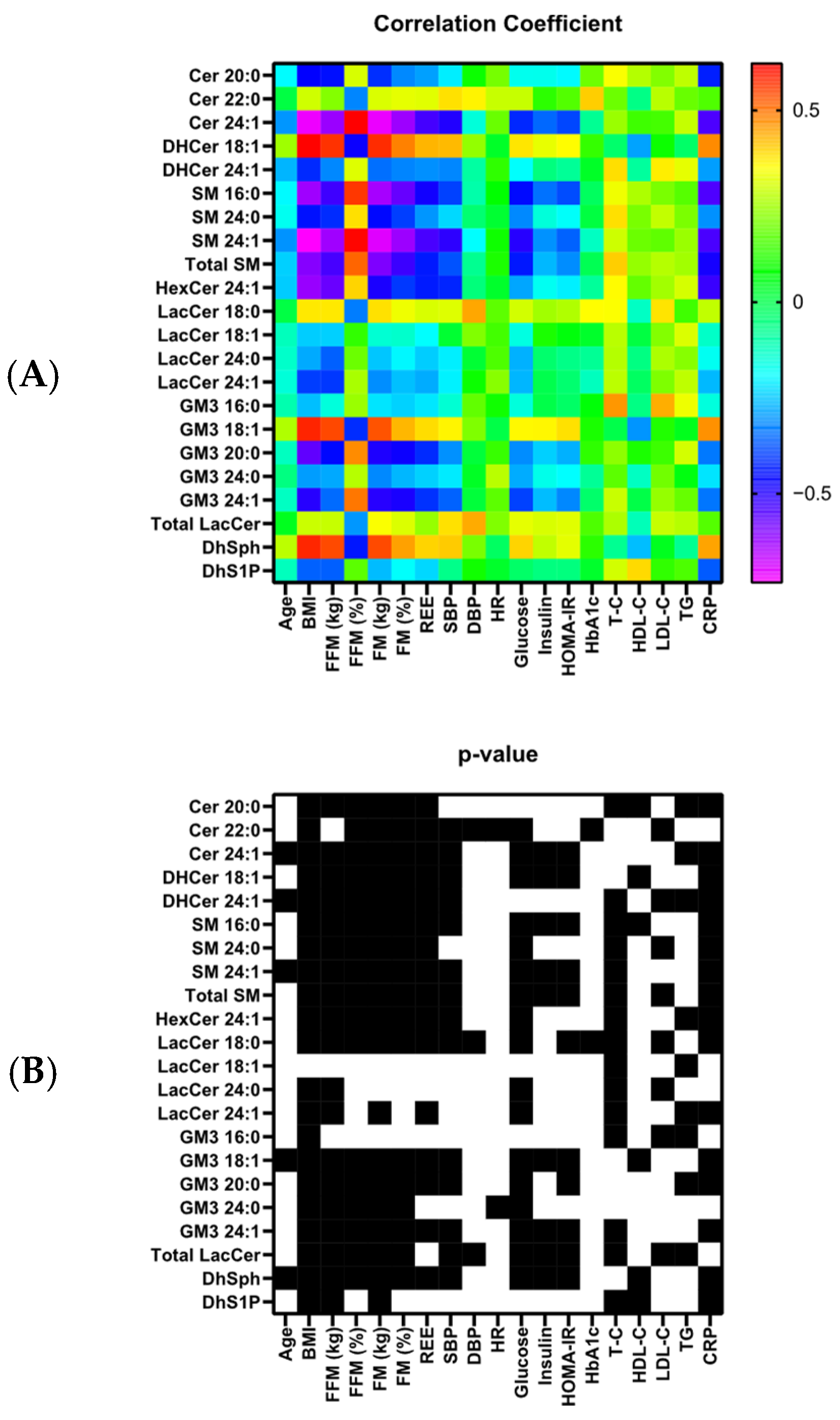

3.3. Correlations of Sphingolipids with Other Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Bulik, C.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Carroll, I.M.; Mehler, P. Reframing Anorexia Nervosa as a Metabo-Psychiatric Disorder. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, H.J.; Yilmaz, Z.; Thornton, L.M.; Hübel, C.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Gaspar, H.; Bryois, J.; Hinney, A.; Leppä, V.M.; Mattheisen, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Eight Risk Loci and Implicates Metabo-Psychiatric Origins for Anorexia Nervosa. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of All-Cause and Suicide Mortality in Mental Disorders: A Meta-Review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edition, F. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013, 21, 591–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, N.; Potter, B.J.; Ukah, U.V.; Low, N.; Israel, M.; Israel, M.; Steiger, H.; Steiger, H.; Healy-Profitós, J.; Paradis, G. Anorexia Nervosa and the Long-Term Risk of Mortality in Women. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, K.T.; Tabri, N.; Thomas, J.J.; Murray, H.B.; Keshaviah, A.; Hastings, E.; Edkins, K.; Krishna, M.; Herzog, D.B.; Keel, P.K.; et al. Recovery from Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa at 22-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Dempfle, A.; Egberts, K.; Kappel, V.; Konrad, K.; Vloet, J.A.; Bühren, K. Outcome of Childhood Anorexia Nervosa-The Results of a Five- to Ten-Year Follow-up Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairhofer, D.; Zeiler, M.; Philipp, J.; Truttmann, S.; Wittek, T.; Skala, K.; Mitterer, M.; Schöfbeck, G.; Laczkovics, C.; Schwarzenberg, J.; et al. Short-Term Outcome of Inpatient Treatment for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa Using DSM-5 Remission Criteria. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silén, Y.; Sipilä, P.N.; Raevuori, A.; Raevuori, A.; Mustelin, L.; Marttunen, M.; Kaprio, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Detection, Treatment, and Course of Eating Disorders in Finland: A Population-Based Study of Adolescent and Young Adult Females and Males. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, L.E.; Yilmaz, Z.; Gaspar, H.; Walters, R.K.; Goldstein, J.; Anttila, V.; Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Ripke, S.; Thornton, L.M.; Hinney, A.; et al. Significant Locus and Metabolic Genetic Correlations Revealed in Genome-Wide Association Study of Anorexia Nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.A.; Hübel, C.; Hübel, C.; Hindborg, M.; Lindkvist, E.B.; Kastrup, A.M.; Yilmaz, Z.; Støving, R.K.; Bulik, C.M.; Bulik, C.M.; et al. Increased Lipid and Lipoprotein Concentrations in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soemedi, H. The Foundations and Development of Lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Simons, K. Lipidomics: Coming to Grips with Lipid Diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meer, G. Cellular lipidomics. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M.; Obeid, L.M. Principles of Bioactive Lipid Signalling: Lessons from Sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymann, M.P.; Schneiter, R. Lipid Signalling in Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kruining, D.; Luo, Q.; van Echten-Deckert, G.; Mielke, M.M.; Bowman, A.P.; Ellis, S.R.; Gil Oliveira, T.; Martinez-Martinez, P. Sphingolipids as Prognostic Biomarkers of Neurodegeneration, Neuroinflammation, and Psychiatric Diseases and Their Emerging Role in Lipidomic Investigation Methods. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, A.; Caregaro, L.; Di Pascoli, L.; Brambilla, F.; Santonastaso, P. Total Serum Cholesterol and Suicidality in Anorexia Nervosa. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, F.I.; Gerl, M.J.; Klose, C.; Surma, M.A.; King, J.A.; Seidel, M.; Weidner, K.; Roessner, V.; Simons, K.; Ehrlich, S. Adverse Effects of Refeeding on the Plasma Lipidome in Young Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.A.; Bilgin, M.; Carlsson, J.; Foged, M.M.; Mortensen, E.L.; Bulik, C.M.; Støving, R.K.; Sjögren, J.M. Elevated Lipid Class Concentrations in Females with Anorexia Nervosa before and after Intensive Weight Restoration Treatment—A Lipidomics Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 2260–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, E.I.; Ruocco, A.; Scazzocchio, B.; Zanchi, G.; Lombardo, C.; Silenzi, A.; Ortona, E.; Varì, R. Gender differences in eating disorders. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1583672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Skodol, A.E.; Bender, D.S.; Oldham, J.M. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5® Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (SCID-5-AMPD); American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brusa, F.; Scarpina, F.; Bastoni, I.; Villa, V.; Castelnuovo, G.; Apicella, E.; Savino, S.; Mendolicchio, L. Short-Term Effects of a Multidisciplinary Inpatient Intensive Rehabilitation Treatment on Body Image in Anorexia Nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M.; Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L.; Martijn, C.; Miles, E. A Meta-Analytic Review of Stand-Alone Interventions to Improve Body Image. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, R.C.; Voderholzer, U.; Naab, S.; Schlegl, S. Increased Urge for Movement, Physical and Mental Restlessness, Fundamental Symptoms of Restricting Anorexia Nervosa? Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, M.; Mattar, L.; Kern, L.; Berthoz, S.; Duclos, J.; Viltart, O.; Godart, N. Physical Activity in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, G.; Vansteelandt, K.; Claes, L.; Probst, M.; Van Mechelen, I.; Vandereycken, W. The Usefulness of Experience Sampling in Understanding the Urge to Move in Anorexia Nervosa. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2006, 18, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, S.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S. Systematic Review of Evidence for Different Treatment Settings in Anorexia Nervosa. World J. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E.; Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Hay, P.; Schmidt, U. Anorexia Nervosa: Aetiology, Assessment, and Treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClave, S.A.; Lowen, C.C.; Kleber, M.J.; McConnell, J.W.; Jung, L.Y.; Goldsmith, L.J. Clinical use of the respiratory quotient obtained from indirect calorimetry. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2003, 27, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, J.B.D.B. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J. Physiol. 1949, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, A.H.; Sullards, M.C.; Allegood, J.C.; Kelly, S.; Wang, E. Sphingolipidomics: High-Throughput, Structure-Specific, and Quantitative Analysis of Sphingolipids by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Methods 2005, 36, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, C.B.M.; Dei Cas, M.; Cianciolo, S.; Fidilio, A.; Lazzara, F.; Paroni, R.; Pignatello, R.; Strettoi, E.; Ghidoni, R.; Drago, F.; et al. Novel Ophthalmic Formulation of Myriocin: Implications in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, C.; Zulueta, A.; Caretti, A.; Roda, G.; Paroni, R.; Dei Cas, M. An Update on Sphingolipidomics: Is Something Still Missing? Some Considerations on the Analysis of Complex Sphingolipids and Free-Sphingoid Bases in Plasma and Red Blood Cells. Metabolites 2022, 12, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boini, K.M.; Xia, M.; Koka, S.; Gehr, T.W.B.; Li, P.-L. Sphingolipids in Obesity and Related Complications. Front. Biosci. 2017, 22, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straczkowski, M.; Kowalska, I. The Role of Skeletal Muscle Sphingolipids in the Development of Insulin Resistance. Rev. Diabet. Stud. RDS 2008, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.C.; Kim, B.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, T.S. Sphingolipid Metabolism and Obesity-Induced Inflammation. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Cline, M.A.; Gilbert, E.R. Chronic Stress and Adipose Tissue in the Anorexic State: Endocrine and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Adipocyte 2020, 9, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoch, M.; Calugi, S.; Lamburghini, S.; Dalle Grave, R. Anorexia Nervosa and Body Fat Distribution: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3895–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanisi, F.; Pace, L.; Fonti, R.; Marra, M.; Sgambati, D.; De Caprio, C.; De Filippo, E.; Vaccaro, A.; Salvatore, M.; Contaldo, F. Evidence of Brown Fat Activity in Constitutional Leanness. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Talbot, C.L.; Chaurasia, B.; Chaurasia, B. Ceramides in Adipose Tissue. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikman, B.T.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides as Modulators of Cellular and Whole-Body Metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4222–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, P.; Donati, C. Pleiotropic Effects of Sphingolipids in Skeletal Muscle. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3725–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Caldwell, M.E.; Eddy, K.T.; Rutkove, S.B.; Breithaupt, L. Anorexia Nervosa and Muscle Health: A Systematic Review of Our Current Understanding and Future Recommendations for Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 56, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Hosoda, H.; Date, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin Is a Growth-Hormone-Releasing Acylated Peptide from Stomach. Nature 1999, 402, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louveau, I.; Gondret, F. Regulation of Development and Metabolism of Adipose Tissue by Growth Hormone and the Insulin-like Growth Factor System. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2004, 27, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovetkina, A.; Nadir, R.; Fung, J.N.M.; Nadjarpour, A.; Beddoe, B. The Physiological Role of Ghrelin in the Regulation of Energy and Glucose Homeostasis. Cureus 2020, 12, e7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Nishi, M.; Doi, A.; Shono, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Shimada, T.; Furuta, H.; Sasaki, H.; Nanjo, K. Ghrelin Inhibits Insulin Secretion through the AMPK–UCP2 Pathway in β Cells. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1503–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Pincelli, A.I.; Corra, B.; Viarengo, R.; Bonomo, S.M.; Galimberti, D.; Scacchi, M.; Scarpini, E.; Cavagnini, F.; Müller, E.E. COMMUNICATION: Plasma Ghrelin Concentrations in Elderly Subjects: Comparison with Anorexic and Obese Patients. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 175, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioletta, A.; Muscogiuri, G.; Sorice, G.P.; Lassandro, A.P.; Mezza, T.; Policola, C.; Salomone, E.; Cipolla, C.; Della Casa, S.; Pontecorvi, A.; et al. In Anorexia Nervosa, Even a Small Increase in Abdominal Fat Is Responsible for the Appearance of Insulin Resistance. Clin. Endocrinol. 2011, 75, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebebrand, J.; Blum, W.F.; Blum, W.F.; Barth, N.; Coners, H.; Englaro, P.; Juul, A.; Ziegler, A.; Warnke, A.; Rascher, W.; et al. Leptin Levels in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa Are Reduced in the Acute Stage and Elevated upon Short-Term Weight Restoration. Mol. Psychiatry 1997, 2, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Cline, D.L.; Glavas, M.M.; Covey, S.D.; Kieffer, T.J. Tissue-Specific Effects of Leptin on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorupskaite, K.; George, J.T.; Anderson, R.A. The Kisspeptin-GnRH Pathway in Human Reproductive Health and Disease. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorr, M.; Miller, K.K. The Endocrine Manifestations of Anorexia Nervosa: Mechanisms and Management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, L.M.; Song, J.L.; Yau, L.F.; Mi, J.N.; Zhang, C.R.; Wu, W.T.; Lai, M.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Wang, J.R.; et al. Alterations of Sphingolipid Metabolism in Different Types of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucki, N.C.; Sewer, M.B. The interplay between bioactive sphingolipids and steroid hormones. Steroids 2010, 75, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, E.; Barbacini, P.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Gelfi, C. Sphingolipids in Obesity and Correlated Co-Morbidities: The Contribution of Gender, Age and Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suemaru, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Hattori, T.; Inoue, H.; Kageyama, J.; Ota, Z. Starvation-Induced Changes in Rat Brain Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) and Pituitary-Adrenocortical Response. Life Sci. 1986, 39, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björntorp, P. Hormonal Control of Regional Fat Distribution. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubello, D.; Sonino, N.; Casara, D.; Girelli, M.E.; Busnardo, B.; Boscaro, M. Acute and Chronic Effects of High Glucocorticoid Levels on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis in Man. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1992, 15, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, M.; Riedl, S.; Uhr, M.; Schmidt, D.; Zhang, X.; Yassouridis, A.; Steiger, A. Ghrelin Affects the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis in Humans by Increasing Free Thyroxine and Decreasing TSH in Plasma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 162, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Mutwalli, H.; Haslam, R.; Keeler, J.L.; Treasure, J.; Himmerich, H. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Levels in People with Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 181, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Hamagaki, S.; Takagi, R.; Taniguchi, A.; Kurimoto, F. Plasma Concentrations of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) and Soluble TNF Receptors in Patients with Bulimia Nervosa. Clin. Endocrinol. 2001, 53, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Lee, S.; Bae, Y.-S. Functional Roles of Sphingolipids in Immunity and Their Implication in Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1110–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, R.C. Carbohydrate Metabolism and Its Regulatory Hormones in Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatry Res.-Neuroimaging 1996, 62, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borodzicz-Jazdzyk, S.; Jażdżyk, P.; Łysik, W.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Sphingolipid Metabolism and Signaling in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 915961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, T.D.; Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M.; Obeid, L.M. Ceramide Synthases at the Centre of Sphingolipid Metabolism and Biology. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattenberg, B.W. The Long and the Short of Ceramides. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 9922–9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Kawai, K.; Yamashita, M.; Shoji, M.; Takakura, S.; Hata, T.; Nakashima, M.; Tatsushima, K.; Tanaka, K.; Sudo, N. Very Long Chain Fatty Acids Are an Important Marker of Nutritional Status in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa: A Case Control Study. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2020, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | AN | NWH | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 28 | 30 | - |

| Age (year) | 23.7 [19.8–30.9] | 28.1 [26.0–32.1] | 0.006 |

| Height (cm) | 1.63 [1.56–1.70] | 1.67 [1.62–1.70] | 0.112 |

| Weight (kg) | 39.3 [36.1–42.1] | 59.5 [54.9–66.4] | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 15.5 [13.9–16.3] | 22.0 [19.7–23.7] | <0.001 |

| FFM (kg) | 33.9 [32.7–38.2] | 46.0 [41.7–49.2] | <0.001 |

| FM (%) | 11.3 [6.5–15.3] | 22.0 [18.3–29.0] | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 100 [90–108] | 117 [110–120] | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 60 [60–70] | 70 [65–72] | 0.019 |

| HR (beats/min) | 72.5 [64.0–86.7] | 70.0 [68.0–73.0] | 0.395 |

| REE (kcal) | 1222 [1189–1276] | 1409 [1311–1559] | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 77.5 [70.5–84.0] | 86.5 [82.0–90.0] | <0.001 |

| Insulin (mU/L) | 3.4 [2.3–6.7] | 7.0 [5.1–9.1] | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.67 [0.42–1.24] | 1.50 [1.10–1.80] | <0.001 |

| Hb1Ac (%) | 5.05 [4.60–5.20] | 5.10 [4.90–5.30] | 0.090 |

| T-C (mg/dL) | 188 [149–219] | 173 [157–201] | 0.479 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 71.5 [63.2–84.7] | 68.5 [62.7–76.5] | 0.308 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 106.5 [77.7–129.7] | 103.5 [85.2–122.0] | 0.895 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 79.0 [60.5–92.7] | 64.0 [47.7–87.5] | 0.290 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.00 [0.00–0.00] | 0.100 [0.01–0.20] | <0.001 |

| Sphingolipid | AN | NWH | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µmol/L) | Median | 25th | 75th | Median | 25th | 75th | |

| Single | |||||||

| Cer 14:0 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.019 | =0.100 |

| Cer 16:0 | 0.511 | 0.455 | 0.589 | 0.471 | 0.421 | 0.516 | =0.109 |

| Cer 18:1 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.016 | =0.403 |

| Cer 18:0 | 0.091 | 0.062 | 0.119 | 0.078 | 0.066 | 0.107 | =0.423 |

| Cer 20:0 | 0.183 | 0.140 | 0.204 | 0.109 | 0.073 | 0.151 | <0.001 |

| Cer 22:0 | 0.523 | 0.378 | 0.608 | 0.616 | 0.457 | 0.688 | =0.027 |

| Cer 24:1 | 1.660 | 1.522 | 1.813 | 0.936 | 0.742 | 1.111 | <0.001 |

| Cer 24:0 | 4.670 | 3.302 | 5.676 | 3.891 | 3.291 | 5.149 | 0.498 |

| DHCer 16:0 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.029 | =0.105 |

| DHCer 18:1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| DHCer 18:0 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.0060 | 0.004 | 0.008 | =0.608 |

| DHCer 24:1 | 0.142 | 0.125 | 0.165 | 0.078 | 0.060 | 0.111 | <0.001 |

| DHCer 24:0 | 0.161 | 0.118 | 0.206 | 0.179 | 0.151 | 0.237 | =0.084 |

| SM 16:0 | 199.394 | 181.426 | 210.668 | 131.678 | 118.543 | 164.700 | <0.001 |

| SM 18:0 | 48.599 | 34.101 | 56.528 | 39.373 | 32.842 | 48.384 | =0.063 |

| SM 18:1 | 27.544 | 21.628 | 32.918 | 24.177 | 20.809 | 29.556 | =0.228 |

| SM 24:0 | 74.601 | 65.881 | 88.859 | 37.160 | 13.185 | 67.927 | <0.001 |

| SM 24:1 | 167.730 | 142.939 | 185.807 | 62.379 | 34.449 | 101.294 | <0.001 |

| HexCer 16:0 | 1.435 | 1.212 | 1.692 | 1.496 | 1.225 | 1.710 | =0.720 |

| HexCer 18:0 | 0.258 | 0.204 | 0.344 | 0.264 | 0.213 | 0.341 | =0.969 |

| HexCer 18:1 | 0.006 | 0.0045 | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.034 | =1.000 |

| HexCer 20:0 | 0.319 | 0.263 | 0.388 | 0.299 | 0.266 | 0.393 | =1.000 |

| HexCer 22:0 | 4.021 | 3.565 | 5.181 | 4.570 | 3.984 | 5.257 | =0.120 |

| HexCer 24:0 | 4.747 | 4.459 | 6.268 | 5.051 | 4.281 | 5.954 | =0.715 |

| HexCer 24:1 | 6.912 | 5.982 | 7.972 | 4.017 | 3.428 | 5.733 | <0.001 |

| LacCer 16:0 | 6.514 | 5.740 | 7.520 | 7.031 | 5.779 | 9.453 | =0.253 |

| LacCer 18:0 | 0.098 | 0.078 | 0.115 | 0.119 | 0.090 | 0.201 | =0.032 |

| LacCer 18:1 | 0.069 | 0.050 | 0.092 | 0.053 | 0.040 | 0.069 | =0.018 |

| LacCer 20:0 | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.120 | 0.087 | 0.040 | 0.112 | =0.164 |

| LacCer 22:0 | 0.436 | 0.331 | 0.508 | 0.393 | 0.091 | 0.498 | =0.213 |

| LacCer 24:0 | 0.402 | 0.328 | 0.520 | 0.227 | 0.009 | 0.379 | =0.001 |

| LacCer 24:1 | 2.775 | 2.201 | 3.324 | 1.362 | 0.186 | 2.112 | <0.001 |

| GM3 16:0 | 2.460 | 2.183 | 2.947 | 1.864 | 1.610 | 2.594 | =0.007 |

| GM3 18:0 | 0.427 | 0.357 | 0.583 | 0.341 | 0.250 | 0.583 | =0.088 |

| GM3 18:1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| GM3 20:0 | 0.207 | 0.160 | 0.267 | 0.120 | 0.070 | 0.144 | <0.001 |

| GM3 22:0 | 0.660 | 0.570 | 0.950 | 0.793 | 0.547 | 1.387 | =0.171 |

| GM3 24:0 | 0.307 | 0.223 | 0.430 | 0.213 | 0.145 | 0.288 | =0.008 |

| GM3 24:1 | 1.453 | 1.103 | 2.203 | 0.781 | 0.593 | 1.191 | <0.001 |

| Sph | 0.103 | 0.091 | 0.110 | 0.098 | 0.087 | 0.120 | =0.963 |

| S1P | 2.448 | 1.610 | 3.311 | 1.866 | 1.314 | 3.726 | =0.246 |

| DHSph | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| DHS1P | 0.978 | 0.694 | 1.095 | 0.413 | 0.293 | 1.062 | =0.001 |

| Sum | |||||||

| Cers | 7.494 | 5.950 | 9.398 | 6.154 | 5.462 | 7.635 | =0.053 |

| DHCers | 0.329 | 0.287 | 0.375 | 0.293 | 0.244 | 0.400 | =0.231 |

| SMs | 525.966 | 470.127 | 556.727 | 292.808 | 233.854 | 419.931 | <0.001 |

| HexCers | 17.816 | 16.181 | 22.274 | 18.401 | 16.562 | 19.909 | =0.963 |

| LacCers | 10.725 | 8.700 | 11.908 | 12.993 | 9.491 | 14.612 | =0.017 |

| GM3s | 5.687 | 4.763 | 6.953 | 6.775 | 3.540 | 10.826 | =0.669 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rigamonti, A.E.; Paroni, R.; Sadikovic, A.; Morano, C.; Bondesan, A.; Caroli, D.; Frigerio, F.; Abbruzzese, L.; Savino, S.; Cella, S.G.; et al. Evaluation of the Sphingolipidomic Profile in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: Relationships with Parameters Related to Body Composition, Cardiovascular Function, Glucometabolic Homeostasis, and Lipoprotein Metabolism. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186482

Rigamonti AE, Paroni R, Sadikovic A, Morano C, Bondesan A, Caroli D, Frigerio F, Abbruzzese L, Savino S, Cella SG, et al. Evaluation of the Sphingolipidomic Profile in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: Relationships with Parameters Related to Body Composition, Cardiovascular Function, Glucometabolic Homeostasis, and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186482

Chicago/Turabian StyleRigamonti, Antonello E., Rita Paroni, Aldijana Sadikovic, Camillo Morano, Adele Bondesan, Diana Caroli, Francesca Frigerio, Laura Abbruzzese, Sandra Savino, Silvano G. Cella, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation of the Sphingolipidomic Profile in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: Relationships with Parameters Related to Body Composition, Cardiovascular Function, Glucometabolic Homeostasis, and Lipoprotein Metabolism" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186482

APA StyleRigamonti, A. E., Paroni, R., Sadikovic, A., Morano, C., Bondesan, A., Caroli, D., Frigerio, F., Abbruzzese, L., Savino, S., Cella, S. G., & Sartorio, A. (2025). Evaluation of the Sphingolipidomic Profile in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: Relationships with Parameters Related to Body Composition, Cardiovascular Function, Glucometabolic Homeostasis, and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6482. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186482