Natural History of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: Long-Term Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Epidemiology of Gastric SETs

4. Natural History of Gastric SETs

5. Risk Factors for Growth and Malignant Potential of Gastric SETs

5.1. Location of SETs

5.2. Initial Size of SETs

5.3. Mucosal Change Overlying SETs

5.4. EUS Findings of SETs

5.5. Histopathology of SETs

6. SETs Located at the MP Layer

6.1. GISTs

6.2. Differential Diagnosis with GISTs

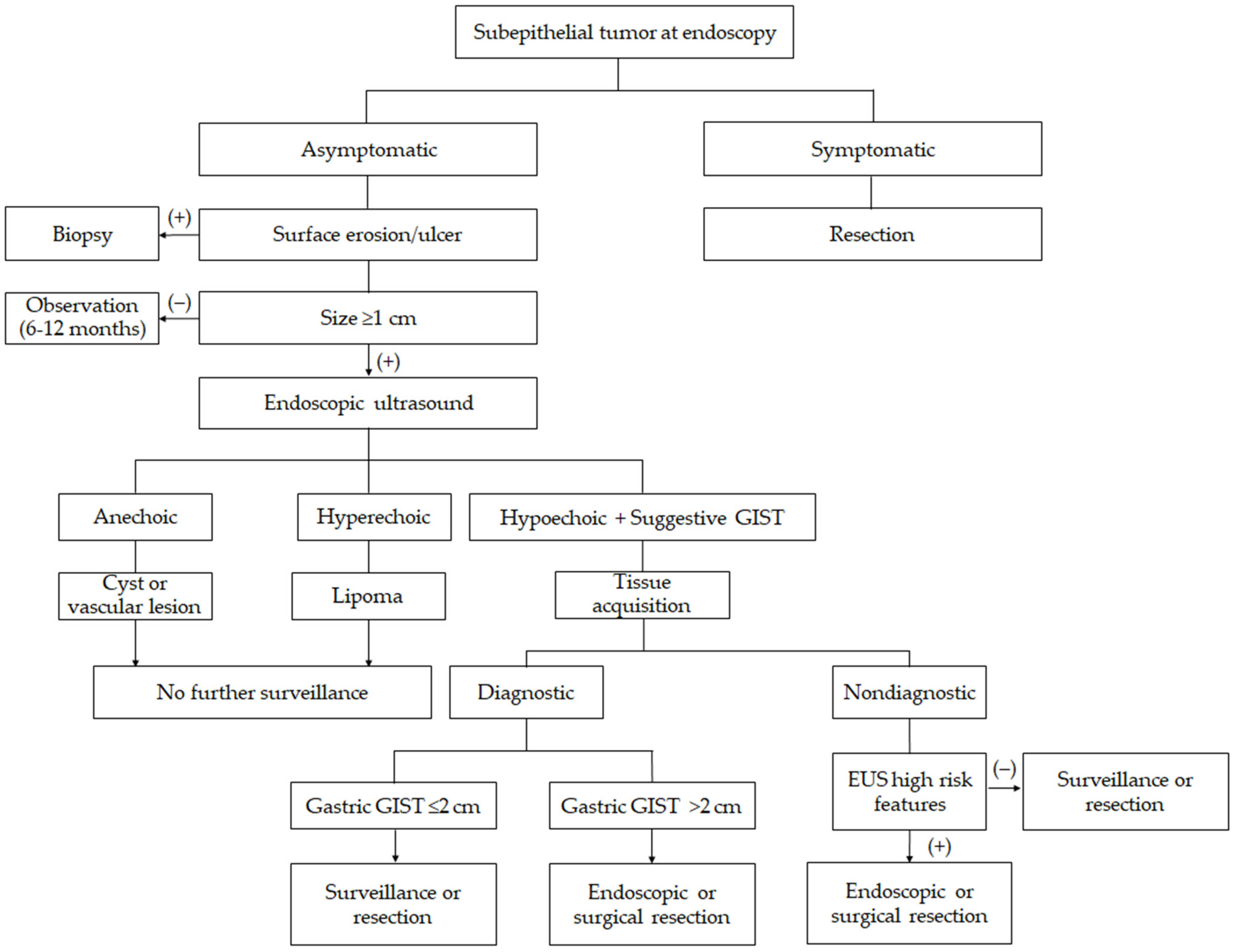

7. Management and Surveillance Strategies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACG | American College of Gastroenterology |

| ESGE | European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

| AGA | American Gastroenterology Association |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| MP | Muscularis propria |

| SET | Subepithelial tumor |

| FNA | Fine-needle aspiration |

| FNB | Fine-needle biopsy |

| MIAB | Mucosal incision-assisted biopsy |

| ROSE | Rapid on-site evaluation |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Deprez, P.H.; Moons, L.M.G.; O’Toole, D.; Gincul, R.; Seicean, A.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Fernandez-Esparrach, G.; Polkowski, M.; Vieth, M.; Borbath, I.; et al. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, B.C.; Bhatt, A.; Greer, K.B.; Lee, L.S.; Park, W.G.; Sauer, B.G.; Shami, V.M. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Lesions. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, D.H.; Yang, M.A.; Song, J.S.; Lee, W.D.; Cho, J.W. Prevalence and natural course of incidental gastric subepithelial tumors. Clin. Endosc. 2024, 57, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, G.H.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, E.K.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; et al. Prevalence, natural progression, and clinical practices of upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions in Korea: A multicenter study. Clin. Endosc. 2023, 56, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.W.; Korean, E.S.D.S.G. Current Guidelines in the Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Tumors. Clin. Endosc. 2016, 49, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H. Systematic Endoscopic Approach for Diagnosing Gastric Subepithelial Tumors. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Son, H.J.; Lee, J.S.; Byun, Y.H.; Suh, H.J.; Rhee, P.L.; Kim, J.J.; Rhee, J.C. Clinical course of subepithelial lesions detected on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Kim, S.G.; Chung, S.J.; Kang, H.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S. Risk of progression for incidental small subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy 2015, 47, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Tominaga, K.; Yamamiya, A.; Inaba, Y.; Kanamori, A.; Kondo, M.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, H.; Kawano, M.; Sato, T.; et al. Natural History of Small Gastric Subepithelial Lesions Less than 20 mm: A Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study (NUTSHELL20 Study). Digestion 2023, 104, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamuro, M.; Okada, H.; Otsuka, M. Natural Course and Long-Term Outcomes of Gastric Subepithelial Lesions: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Carucci, P.; Repici, A.; Pellicano, R.; Mezzabotta, L.; Goss, M.; Magnolia, M.R.; Saracco, G.M.; Rizzetto, M.; De Angelis, C. The natural history of gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors arising from muscularis propria: An endoscopic ultrasound survey. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2009, 43, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Jung, H.Y.; Choi, K.D.; Song, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, K.S.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, J.H. Natural history of asymptomatic small gastric subepithelial tumors. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 45, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.L.; Wu, K.L.; Changchien, C.S.; Chuah, S.K.; Chiu, Y.C. Endosonographic surveillance of 1–3 cm gastric submucosal tumors originating from muscularis propria. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.S.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Yao, M.H.; Khan, N.; Hu, B. Clinical course of suspected small gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 12, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kang, S.; Lee, E.; Choi, J.; Chung, H.; Cho, S.J.; Kim, S.G. Gastric subepithelial tumor: Long-term natural history and risk factors for progression. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 5232–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamuro, M.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Inaba, T.; Matsueda, K.; Nagahara, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Doyama, H.; Mizuno, M.; Yada, T.; Kawai, Y.; et al. Results of the interim analysis of a prospective, multicenter, observational study of small subepithelial lesions in the stomach. Dig. Endosc. 2024, 36, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanowa, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Sakurai, S.; Hishima, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; Saito, K.; Hosoya, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Funata, N. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum. Pathol. 2006, 37, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Lasota, J.; Sobin, L.H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach in children and young adults: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 44 cases with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005, 29, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2006, 23, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.W.; Park, Y.D.; Chung, Y.J.; Cho, C.M.; Tak, W.Y.; Kweon, Y.O.; Kim, S.K.; Choi, Y.H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: Endosonographic differentiation in relation to histological risk. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 2069–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chak, A.; Canto, M.I.; Rosch, T.; Dittler, H.J.; Hawes, R.H.; Tio, T.L.; Lightdale, C.J.; Boyce, H.W.; Scheiman, J.; Carpenter, S.L.; et al. Endosonographic differentiation of benign and malignant stromal cell tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1997, 45, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Park, D.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, C.W.; Heo, J.; Song, G.A. Is it possible to differentiate gastric GISTs from gastric leiomyomas by EUS? World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 3376–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.D.; Berman, J.J.; Corless, C.; Gorstein, F.; Lasota, J.; Longley, B.J.; Miettinen, M.; O’Leary, T.J.; Remotti, H.; Rubin, B.P.; et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akahoshi, K.; Oya, M.; Koga, T.; Shiratsuchi, Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2806–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkill, G.J.; Badran, M.; Al-Muderis, O.; Meirion Thomas, J.; Judson, I.R.; Fisher, C.; Moskovic, E.C. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology 2003, 226, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Ahn, J.Y.; Na, H.K.; Jung, K.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, K.D.; Song, H.J.; Lee, G.H.; Jung, H.Y. Natural history of gastric leiomyoma. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 2726–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yang, N.; Pi, M.; Yu, W. Current status of the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal schwannoma. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, Y.H.; Choi, S.R.; Lee, B.E.; Kim, G.H. Gastric glomus tumor: Analysis of endosonographic characteristics and computed tomographic findings. Dig. Endosc. 2013, 25, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharzehi, K.; Sethi, A.; Savides, T. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2435–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, S.; Tateishi, U.; Nakamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Sakurai, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Kanda, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Cho, H.; Nishida, T.; et al. English version of Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines 2022 for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) issued by the Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 29, 647–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaleh, M.; Bhagat, V.; Dellatore, P.; Tyberg, A.; Sarkar, A.; Shahid, H.M.; Andalib, I.; Alkhiari, R.; Gaidhane, M.; Kedia, P.; et al. Subepithelial tumors: How does endoscopic full-thickness resection & submucosal tunneling with endoscopic resection compare with laparoscopic endoscopic cooperative surgery? Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E1491–E1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.G. Endoscopic Treatment for Gastric Subepithelial Tumor. J. Gastric. Cancer 2024, 24, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.S.; Joo, M.K. Advancements in endoscopic resection of subepithelial tumors: Toward safer, recurrence-free techniques. Clin. Endosc. 2025, 58, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, O.; Higuchi, K.; Koizumi, E.; Iwakiri, K. Advancements in Endoscopic Treatment for Gastric Subepithelial Tumors. Gut Liver 2025, 19, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ahn, J.Y.; Jung, H.Y.; Kang, S.; Song, H.J.; Choi, K.D.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Na, H.K.; Park, Y.S. Endoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor using clip-and-cut endoscopic full-thickness resection: A single-center, retrospective cohort in Korea. Clin. Endosc. 2024, 57, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year) | No. Lesions | Population /Design | Follow-Up Period | Size Increase | Malignancy Yield | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of Growth | Results | Increase Relative to Initial Size | |||||

| Bruno et al. (2009) [11] | 49 | SETs from MP <3 cm/ prospective | 31.0 months (mean) | ≥25% increase | 5/49 (10.2%) | NA | 0% overt malignancy; 3 of 4 resected lesions were GISTs (all very-low- and low-risk); 1 glomus tumor |

| Lim et al. (2010) [7] | 130 | SETs/ retrospective | 59.1 months (mean) | ≥25% and ≥5 mm | 7/130 (5.4%) | NA | 2 of 3 resected lesions ≥ 3 cm were GISTs (intermediate- and high-risk); 1 schwannoma |

| Kim et al. (2011) [12] | 989 | SETs ≤30 mm/ retrospective | 24 months (median) | ≥25% increase | 84/989 (8.5%) | <10 mm: 29/450 (6.4%) 10–20 mm: 38/366 (10.4%) 20–30 mm: 17/173 (9.8%) | Among 25 resected lesions for changes, 19 were GISTs (3 high-risk, 4 intermediate-risk) |

| Song et al. (2015) [8] | 640 | SETs/ retrospective | 47.3 months (mean) | ≥25% increase | 27/640 (4.2%) | NA | 0% clinical malignancy during follow-up; 2 of 3 resected lesions were GISTs (low- or intermediate-risk) |

| Hu et al. (2017) [13] | 88 | SETs 1–3 cm from MP/retrospective | 24.6 (stationary subgroup)/30.7 (progressive subgroup) months (mean) | ≥20% increase | 25/88 (28.4%) | NA | Among 17 surgically resected cases, 13 were GISTs (1 high-risk, 2 intermediate-risk) |

| Ye et al. (2020) [14] | 410 | SETs ≤20 mm/ retrospective | 28 months (median) | Not specified | 8/410 (2.0%) | <10 mm: 2/291 (0.7%) 10–20 mm: 6/119 (5.0%) | 5 of 6 resected lesions due to increased size were GISTs (2 intermediate-risk, 3 low-risk) |

| Kim et al. (2022) [15] | 1859 | SETs/ retrospective | 59.4 months (mean) | ≥25% increase | 138/1859 (7.4%) | <10 mm: 34/840 (4.1%) 10–20 mm: 59/673 (8.8%) >20 mm: 34/346 (13.0%) | 50 of the 73 resected lesions were GISTs (4 high-risk showed increased size) |

| Abe et al. (2023) [9] | 824 | SETs ≤20 mm/ multicenter retrospective | 5 years (median) | ≥20% increase | 70/824 (8.5%) | 1–5 mm: 16/298 (5.4%) 6–10 mm: 23/344 (6.7%) 11–15 mm: 20/112 (17.9%) 15–20 mm: 11/70 (15.7%) | 26 of the 34 resected lesions were GISTs (1 high-risk) |

| Choe et al. (2023) [4] | 135 | SETs ≥1cm/ multicenter retrospective | 52 months (median) | Not specified | 20/135 (14.8%) | 10–20 mm: 13/113 (11.5%) >20 mm: 7/22 (31.8%) | Among 20 resected cases, 12 were GISTs and 1 was lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma |

| Heo et al. (2024) [3] | 262 | SETs/ retrospective | 58 months (median) | >25% increase and >5 mm | 22/262 (8.4%) | NA | 0% developed overt malignancy. 2 of 7 resected lesions were GISTs (1 intermediate-risk, 1 low-risk) |

| Iwamuro et al. (2024) [16] | 610 | SETs ≤20 mm/ prospective multicenter | 4.6 years (mean) | ≥5 mm increase | 32/610 (5.7%) | NA | 25 of 30 resected lesions were GISTs |

| Risk Factors | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|

| Endoscopic findings | |

| Proximal location (fundus/body) | 90% of microscopic GISTs were found in the fundus/body [17] Mid-third gastric location (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.08–2.52) [15] Antrum SETs are frequently benign (pancreatic rests) with minimal growth [6] |

| Larger initial size | Lesions 10–30 mm grew faster than <10 mm lesions [12] Progressive group had initially larger size (p = 0.020) [13] Growth rates correlate with baseline size (r = 0.44) [8] Size ≥13.5 mm predicted growth in small SETs [9] GIST risk classification is size-dependent (metastatic risk rises sharply >5 cm) [18,19] Large initial tumor size (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05) [15] |

| Overlying mucosal changes (ulceration, erosion, redness) | 3.6-fold higher odds of growth if mucosal ulcer/erosion present [8] Surface ulcer or erosion (OR: 2.47, 95% CI: 1.21–5.06) [15] |

| EUS findings | |

| Irregular border | Irregular/lobulated margins conferred OR 4.6 for significant enlargement [3] Progressing lesions had more irregular borders than stable lesions (40% vs. 11%) [13] |

| Heterogeneous internal echo | Uniformly homogenous hypoechoic lesions rarely enlarged [13] Heterogeneous echotexture was more frequent in lesions that grew [13] Mixed echogenicity/cystic areas were linked to GISTs that increased in size [9] |

| Internal cystic spaces | Presence of cystic change was a significant risk factor for growth in small GISTs [9] Cystic areas were often seen in large or high-risk GISTs (reflecting necrosis) [6] |

| Histopathology | |

| GISTs (versus benign lesions) | In univariate analysis, GISTs had more frequent size increase than other tumor types [12] All lesions that progressed to require resection were ultimately GISTs in several series [10,11] Leiomyomas, lipomas, etc., rarely grew or turned malignant [13] High-risk features (mitotic count, size >5 cm, etc.) in GISTs correlate with an 80% chance of metastasis (whereas small low-mitotic GISTs with 2–3% risk) [19] |

| Category | ACG (American College of Gastroenterology) | ESGE (European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy) | AGA (American Gastroenterological Association) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial evaluation | EUS is suggested preferentially over endoscopy or contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging. | EUS is recommended as the best tool to characterize SET features. | EUS is the modality of choice for indeterminate SET when biopsies are nondiagnostic. |

| Tissue acquisition | EUS with tissue acquisition is suggested to improve diagnostic accuracy. EUS-FNB alone or EUS-FNA with ROSE; unroofing or tunnel biopsy if nondiagnostic. | Tissue diagnosis for SETs with features suggestive of GIST, if they are of size >20 mm, or have high risk stigmata, or require surgical resection or oncological treatment SETs < 20 mm: MIAB (first choice) or EUS-FNB (second choice) SETs ≥ 20 mm: EUS-FNB or MIAB equally effective | SETs arising from the submucosa: using tunnel biopsy (or deep-well biopsies), EUS-FNA, EUS-FNB, or advanced endoscopic techniques (unroofing or endoscopic submucosal resection) SETs arising from MP: EUS-FNB or EUS-FNA to determine whether the lesion is a GIST or leiomyoma |

| Benign lesions | No specific details provided | ESGE recommends against surveillance of asymptomatic gastrointestinal leiomyomas, lipomas, heterotopic pancreas, granular cell tumors, schwannomas, and glomus tumors, if the diagnosis is clear. | SETs that have an endoscopic appearance consistent with lipomas, pancreatic rests, and duplication cysts do not need further evaluation or surveillance. |

| Asymptomatic lesions without a definite diagnosis | There is insufficient evidence to make definitive recommendations regarding surveillance intervals when resection is not undertaken. | ESGE suggests surveillance of asymptomatic gastric SETs without definite diagnosis, with EGD at 3–6 months; <10 mm lesions every 2–3 years and 10–20 mm lesions every 1–2 years. >20 mm (if not resected): EGD+EUS at 6 months and then at 6–12 month intervals. SETs < 20 mm and of unknown histology after failure of attempts to obtain a diagnosis: endoscopic resection is an option to avoid unnecessary follow-up | SETs arising from MP < 2 cm: surveillance using EUS; otherwise tailored by features. |

| Symptomatic or ulcerated bleeding lesions | All guidelines recommend resection regardless of the size of the lesion and without a pre-resection diagnosis. | ||

| Gastric GIST < 2 cm | There is insufficient evidence to recommend surveillance vs. resection | Surveillance or resection is both acceptable; resection considered after multidisciplinary discussion. | Can be surveilled using EUS |

| Gastric GIST ≥ 2 cm | Resection | Resection | Resection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, H.K.; Kim, G.H. Natural History of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: Long-Term Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186354

Jeon HK, Kim GH. Natural History of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: Long-Term Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186354

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Hye Kyung, and Gwang Ha Kim. 2025. "Natural History of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: Long-Term Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186354

APA StyleJeon, H. K., & Kim, G. H. (2025). Natural History of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors: Long-Term Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186354