Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Pectopexy

Abstract

1. Introduction

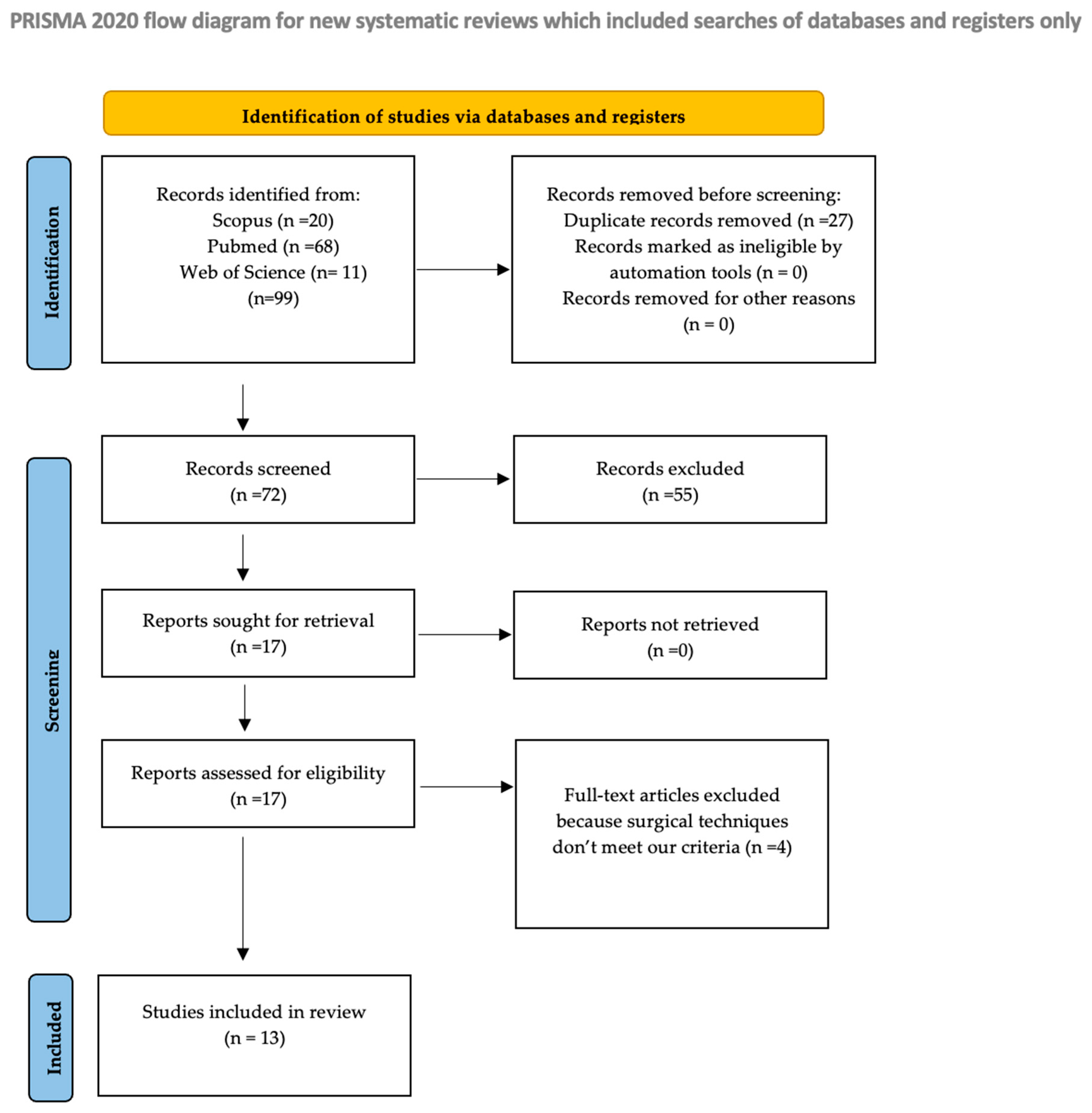

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Acquisition and Risk of Bias

2.4. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POP | Pelvic organ prolapse |

| LS | laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy |

| LP | Laparoscopic pectopexy |

| PROs | patient-reported outcomes |

| QoL | quality of life |

| FSFI | Female Sexual Function Index |

| P-QOL | Prolapse Quality of Life |

| PFDI-20 | Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory |

| PFIQ-7 | Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire |

| PISQ-12 | Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire |

| PGI-I | Patient Global Impression of Improvement |

| ISI | Incontinence Severity Index |

| ICIQ-SF | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire—Short Form |

| UDI-6 | Urogenital Distress Inventory |

| IIQ-7 | Incontinence Impact Questionnaire |

| EPIQ | Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire |

| I-QOL | Incontinence Quality of Life |

| PISQ-IR | Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire IUGA-Revised |

| POPDI-6 | Pelvic organ Prolapse Distress Inverntory-6 |

| UI | Urinary incontinence |

| IUGA | International Urogynecological Association |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SSHP | Sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy |

| SSLF | Sacrospinous ligament fixation |

References

- Machin, S.E.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Review of the Aetiology, Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Menopause Int. 2011, 17, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.F.; Qatawneh, A.M.; Dwyer, P.L.; Carey, M.P.; Cornish, A.; Schluter, P.J. Abdominal Sacral Colpopexy or Vaginal Sacrospinous Colpopexy for Vaginal Vault Prolapse: A Prospective Randomized Study. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akladios, C.Y.; Dautun, D.; Saussine, C.; Baldauf, J.J.; Mathelin, C.; Wattiez, A. Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy for Female Genital Organ Prolapse: Establishment of a Learning Curve. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 149, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, C.; Noé, K.G. Laparoscopic Pectopexy: A New Technique of Prolapse Surgery for Obese Patients. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2011, 284, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsillidi, A.; Protopapas, A.; Gkrozou, F.; Daniilidis, A. Laparoscopic Pectopexy for the Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) How Why When: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2025, 17, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsaei, M.; Hadizadeh, A.; Hadizadeh, S.; Tarafdari, A. Comparing the Efficacy of Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2025, 32, 672–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S. Intermediate-Term Follow-up of Laparoscopic Pectopexy Cases and Their Effects on Sexual Function and Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Nai, M.; Xu, Q.; Jin, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, L. Comparison of Efficacy between Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Laparoscopic High Uterosacral Ligament Suspension in the Treatment of Apical Prolapse-Short Term Results. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astepe, B.S.; Karsli, A.; Köleli, I.; Aksakal, O.S.; Terzi, H.; Kale, A. Intermediate-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Vaginal Sacrospinous Fixation: A Comparative Study. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2019, 45, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obut, M.; Oğlak, S.C.; Akgöl, S. Comparison of the Quality of Life and Female Sexual Function Following Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy in Apical Prolapse Patients. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2021, 10, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoiwal, K.; Dash, K.C.; Gaurav, A.; Chaturvedi, J. Comparison of Laparoscopic Pectopexy with the Standard Laparoscopic Sacropexy for Apical Prolapse: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2023, 24, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karslı, A.; Karslı, O.; Kale, A. Laparoscopic Pectopexy: An Effective Procedure for Pelvic Organ Prolapse with an Evident Improvement on Quality of Life. Prague Med. Rep. 2021, 122, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahaoglu, A.E.; Bakir, M.S.; Peker, N.; Bagli, İ.; Tayyar, A.T. Modified Laparoscopic Pectopexy: Short-Term Follow-up and Its Effects on Sexual Function and Quality of Life. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Liu, C. Laparoscopic Pectopexy with Native Tissue Repair for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2023, 307, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, P.; Grzybowska, M.E.; Sawicki, S.; Futyma, K.; Wydra, D.G. Perioperative and Long-Term Anatomical and Subjective Outcomes of Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension for POP-Q Stages II–IV Apical Prolapse. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, P.; Horng, H. Efficacy of Minimally Invasive Pectopexy with Concomitant I-stop-mini Sling for Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Overt Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 162, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Si, K.; Dai, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; He, J.; Wu, G. Effectiveness of Laparoscopic Pectopexy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse Compared with Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 833–840.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, P.L.; Hoang, T.H.; Ho, T.T.H.; Pham, H.P.; Vo, V.D. Initial Evaluation Treatment Results of Laparoscopic Pectopexy in the Management of Uterine Prolapse. Tạp Chí Phụ Sản 2023, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinskaya, E.D.; Gasparov, A.S.; Babicheva, I.A.; Kolesnikova, S.N. Improving of Long-Term Follow-up after Cystocele Repair. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, S.; Bandiera, S.; Cavallaro, A.; Cianci, S.; Vitale, S.G.; Rugolo, S. Quality of Life and Sexual Changes after Double Transobturator Tension-Free Approach to Treat Severe Cystocele. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 151, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Caruso, S.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Valenti, G.; Rossetti, D.; Cianci, S.; Cianci, A. Biocompatible Porcine Dermis Graft to Treat Severe Cystocele: Impact on Quality of Life and Sexuality. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2016, 293, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboia, D.M.; Firmiano, M.L.V.; de Castro Bezerra, K.; Vasconcelos Neto, J.A.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M. Impacto Dos Tipos de Incontinência Urinária Na Qualidade de Vida de Mulheres. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.D.; Brubaker, L.; Nygaard, I.; Wheeler, T.L.; Schaffer, J.; Chen, Z.; Spino, C. Defining Success After Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A Multidimensional Self-Report Instrument for the Assessment of Female Sexual Function. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.G.; Coates, K.W.; Kammerer-Doak, D.; Khalsa, S.; Qualls, C. A Short Form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003, 14, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.G.; Rockwood, T.H.; Constantine, M.L.; Thakar, R.; Kammerer-Doak, D.N.; Pauls, R.N.; Parekh, M.; Ridgeway, B.; Jha, S.; Pitkin, J.; et al. A New Measure of Sexual Function in Women with Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFD): The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Haya, N.; Brown, J. Surgery for Women with Apical Vaginal Prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, CD012376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, K.-G.; Schiermeier, S.; Alkatout, I.; Anapolski, M. Laparoscopic Pectopexy: A Prospective, Randomized, Comparative Clinical Trial of Standard Laparoscopic Sacral Colpocervicopexy with the New Laparoscopic Pectopexy—Postoperative Results and Intermediate-Term Follow-Up in a Pilot Study. J. Endourol. 2015, 29, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Author, Year) | Design | Sample Size (n) | Mean Follow-Up | PROMs Used | Main Findings | Overall Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erdem et al., 2022 [8] | Cross-sectional | 35 | 28.9 ± 5.9 months | FSFI, P-QOL | Significant improvement in all FSFI and P-QOL domains (p < 0.001) (Within-group comparison) | High quality |

| Peng et al., 2023 [9] | Retrospective cohort | 78 | 12 months | PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, PISQ-12 | Significantly improved postoperative (p < 0.05) The PISQ-12 scores in laparoscopic uterine pectopexy group were significantly higher than that in the other two groups (p < 0.05) (Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Astepe et al., 2019 [10] | Comparative cohort | 36 (LP) | 13.1 months | PISQ-12, P-QOL | Significantly improved postoperative LP had better PISQ-12 scores compared to SSF (38.21 ± 5.69 vs. 36.86 ± 3.15) but similar P-QOL scores (Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Obut et al., 2021 [11] | Prospective randomized | 32 (LP) | 12 months | FSFI, P-QOL | Significant improvement in all FSFI and P-QOL domains in both LP and laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy groups (p < 0.001) (Within-group and Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Khoiwal et al., 2022 [12] | RCT | 15 (LP) | 6 months | PGI-I, P-QOL, PISQ-12 | Significant improvement in all domains in LP and LS groups PGI-I (p = 0.006 vs. 0.009) PISQ-12 (p < 0.001 in both groups) P-QOL(p < 0.001 in both groups)—no difference between the two groups (Within-group and Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Karslı et al., 2021 [13] | Prospective | 31 | 3 months | P-QOL, PISQ-12, UDI-6, IIQ-7 | Significant improvement in all domains (p =0.001) (Within-group comparison) | High quality |

| Tahaoglu et al., 2017 [14] | Observational | 22 | 10.4 months | FSFI, P-QOL | Significant improvement in all FSFI and P-QOL domains (p < 0.05) (Within-group comparison) | High quality |

| Yu et al., 2023 [15] | Prospective | 49 | 15 months | PFDI-20, PFIQ-7 | Significant improvement in all FSFI and P-QOL domains (p < 0.001) (Within-group comparison) | High quality |

| Szymczak et al., 2022 [16] | Prospective observational | 53 | 26.9 ± 12 months | PGI-I, ISI, EPIQ #35, PFIQ-7, PFDI-20 | PGI-I: postoperative improvement in 75.5% of the LP patients and 44 (72.1%) SSLF patients. Improvement in PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 (p < 0.04) EPIQ #35 was significantly reduced (p < 0.001) ISI: no postoperative deterioration of UI symptoms (Within-group comparison) All scores did not differ between the LP and SSLF/SSHP groups. (Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Chao et al., 2022 [17] | Retrospective cohort | 30 (LP) | 12 months | UDI-6, ICIQ-SF, POPDI-6, PISQ-IR | UDI-6, ICIQ-SF, and POPDI-6 improved significantly (Within-group comparison) No significant differences in the mean difference in postoperative and preoperative UDI-6 (p = 0.834), ICIQ-SF (p = 0.861), POPDI-6 (p = 0.775) scores between LP and LS groups. No significant differences in the mean difference in postoperative and preoperative PISQ-IR question 9 (p = 0.351), PISQ-IR question 11 (p = 0.715), PISQ-IR question 18 (p = 0.192), or PISQ-IR question 19a (p = 0.106) between the two groups. (Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Yang et al., 2023 [18] | Prospective cohort | 102 (LP) | 12 months | PFDI-20, I-QOL | PFDI-20, I-QOL scores had improved significantly LP group showed a greater percent decrease in PFDI-20 and greater percent increase in I-QOL from baseline compared to LS group (Between-group comparison) | High quality |

| Vo et al., 2023 [19] | Retrospective case series | 58 | 6 months | PFDI-20, PFIQ-7 | PFDI-20 from 130 → 8 and PFIQ-7 score 148 → 10 at 3 months; 0 at 6 months for both scores (Within-group comparison) | Moderate quality |

| Dubinskaya et al., 2022 [20] | Prospective | 22 | 12 months | ICIQ-UI-SF, ICIQ-V, PGI-I | All scores improved significantly (p < 0.001) (Within-group comparison) | High quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pitsillidi, A.; Grigoriadis, G.; Vona, L.; Noé, G.; Daniilidis, A. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Pectopexy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176318

Pitsillidi A, Grigoriadis G, Vona L, Noé G, Daniilidis A. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Pectopexy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176318

Chicago/Turabian StylePitsillidi, Anna, Georgios Grigoriadis, Laura Vona, Guenter Noé, and Angelos Daniilidis. 2025. "Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Pectopexy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176318

APA StylePitsillidi, A., Grigoriadis, G., Vona, L., Noé, G., & Daniilidis, A. (2025). Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Pectopexy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176318