From First Breathless Episode to Final Diagnosis and Treatment: A Case Report on Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

2.1. Patient Information

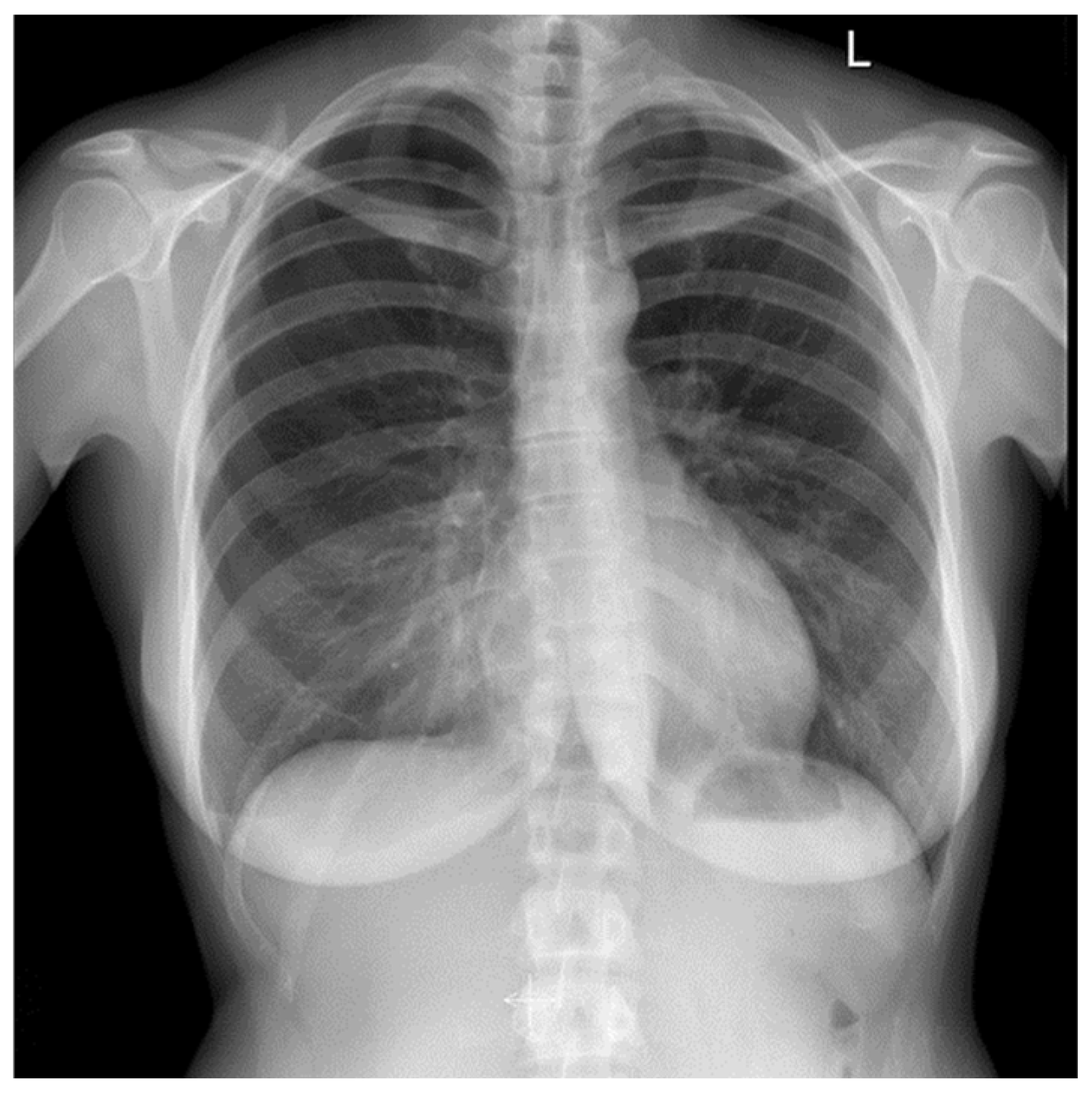

2.2. Clinical Findings

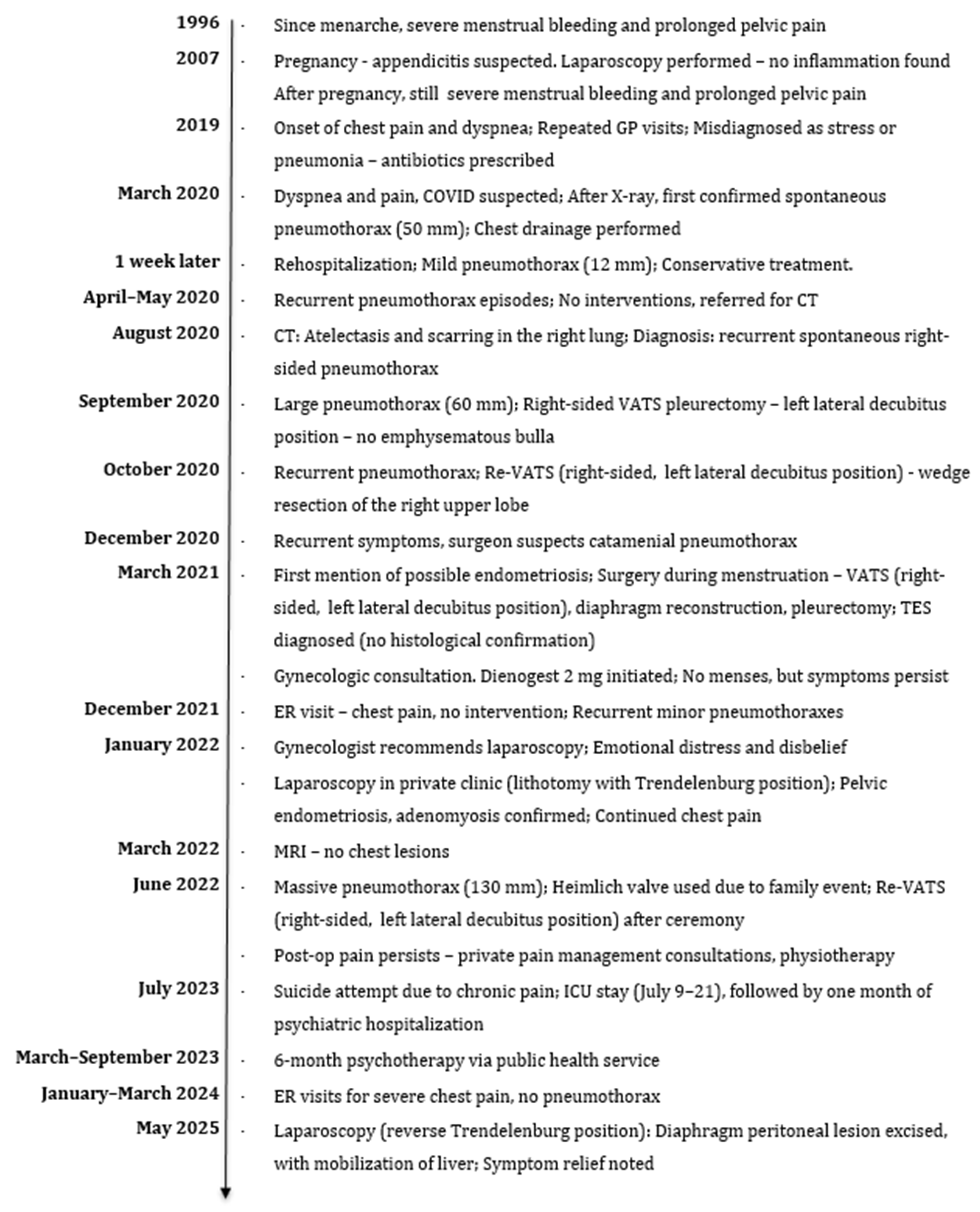

2.3. Timeline

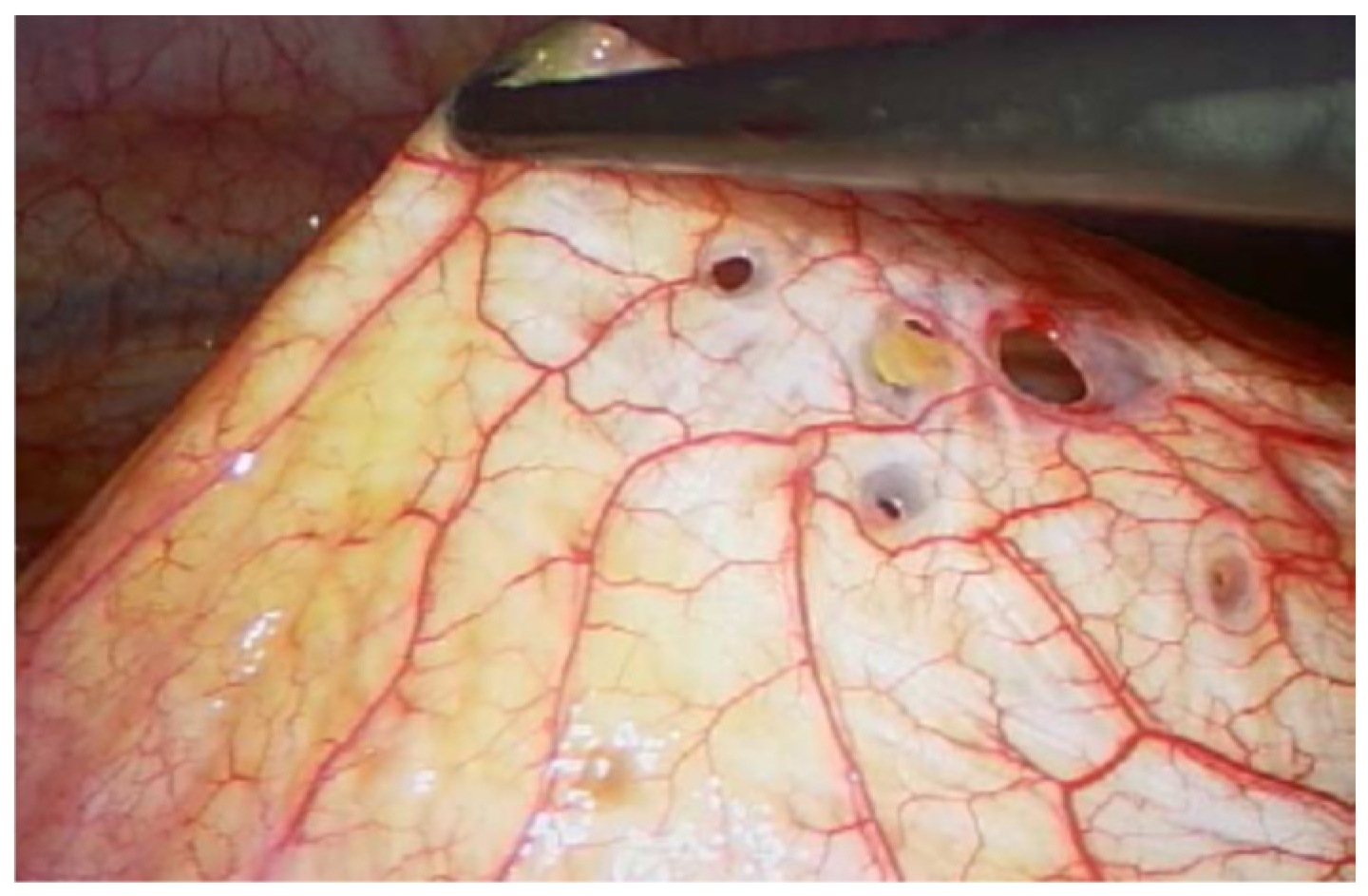

2.4. Diagnostic Assessment and Therapeutic Intervention

2.5. Follow-Up and Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TES | Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome |

| VATS | Video Assisted Thoracoscopy |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone |

| BSGE | British Society for Gynecological Endoscopy |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| PR | Progesterone Receptor |

| DWI | Diffusion Weighted Imaging |

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

References

- Nezhat, C.; Amirlatifi, N.; Najmi, Z.; Tsuei, A. Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review and Multidisciplinary Approach to Management. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamceva, J.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahall, V.; De Barry, L.; Singh, K. Thoracic Endometriosis Masquerading as Meigs’ Syndrome in a Young Woman: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep. Women’s Health 2022, 36, e00452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, E.; Makunja, R.; Maoga, J.B.; Mwaura, A.N.; Riaz, M.A.; Omwandho, C.O.A.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Konrad, L. The Importance of Stromal Endometriosis in Thoracic Endometriosis. Cells 2021, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igai, H.; Sawabata, N.; Obuchi, T.; Matsutani, N.; Tsuboshima, K.; Okamoto, S.; Hayashi, A. Current Situation of Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Respir. Investig. 2024, 62, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Main, J.; Paka, C.; Nezhat, A.; Beygui, R.E. Multidisciplinary Treatment for Thoracic and Abdominopelvic Endometriosis. JSLS J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2014, 18, e2014-00312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, T.; Koga, K.; Osuga, Y. Extra-Pelvic Endometriosis: A Review. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naem, A.; Andrikos, A.; Constantin, A.S.; Khamou, M.; Andrikos, D.; Laganà, A.S.; De Wilde, R.L.; Krentel, H. Diaphragmatic Endometriosis—A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis of the Patients’ Demographics, Symptomatology, and Long-Term Treatment Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E. Endometriosis Caused by Retrograde Menstruation: Now Demonstrated by DNA Evidence. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Khoyloo, F.; Tsuei, A.; Armani, E.; Page, B.; Rduch, T.; Nezhat, C. The Prevalence of Endometriosis in Patients with Unexplained Infertility. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE Guidelines for Case Reports: Explanation and Elaboration Document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M.; Berg, L.; Gamaleldin, I.; Vyas, S.; Vashisht, A. The Management of Women with Thoracic Endometriosis: A National Survey of British Gynaecological Endoscopists. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2021, 12, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T.; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health Consortium. Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life and Work Productivity: A Multicenter Study across Ten Countries. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 366–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Alifano, M.; Plu-Bureau, G.; Camilleri-Broet, S.; Rousset, P.; Regnard, J.-F.; Gompel, A. Catamenial Pneumothorax and Endometriosis-Related Pneumothorax: Clinical Features and Risk Factors. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larraín, D.; Suárez, F.; Braun, H.; Chapochnick, J.; Diaz, L.; Rojas, I. Thoracic and Diaphragmatic Endometriosis: Single-Institution Experience Using Novel, Broadened Diagnostic Criteria. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2018, 19, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriaco, P.; Muriana, P.; Lembo, R.; Carretta, A.; Negri, G. Treatment of Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Review. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiannis, A.; Seckin, T.; Murphy, C.; Seckin, T.; Chu, A. Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome and Quality of Life [ID 1580]. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 145, 18S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Armani, E.; Chen, H.-C.C.; Najmi, Z.; Lindheim, S.R.; Nezhat, C. Use of the Free Endometriosis Risk Advisor App as a Non-Invasive Screening Test for Endometriosis in Patients with Chronic Pelvic Pain and/or Unexplained Infertility. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Lindheim, S.R.; Backhus, L.; Vu, M.; Vang, N.; Nezhat, A.; Nezhat, C. Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. JSLS J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2019, 23, e2019-00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, P.; Gregory, J.; Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Hugon-Rodin, J.; Regnard, J.-F.; Chapron, C.; Coste, J.; Golfier, F.; Revel, M.-P. MR Diagnosis of Diaphragmatic Endometriosis. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 3968–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, I.; Pospisilova, E.; Kolostova, K.; Maly, V.; Stanek, I.; Lischke, R.; Schutzner, J.; Pawlak, I.; Bobek, V. Circulating Endometrial Cells in Women with Spontaneous Pneumothorax. Chest 2020, 157, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjański, T.; Sowa, K.; Czapla, A.; Rzyman, W. Catamenial Pneumothorax—A Review of the Literature. Kardiochirurgia Torakochirurgia Pol. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 13, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quercia, R.; De Palma, A.; De Blasi, F.; Carleo, G.; De Iaco, G.; Panza, T.; Garofalo, G.; Simone, V.; Costantino, M.; Marulli, G. Catamenial Pneumothorax: Not Only VATS Diagnosis. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1156465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeraswamy, A.; Lewis, M.; Mann, A.; Kotikela, S.; Hajhosseini, B.; Nezhat, C. Extragenital Endometriosis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 53, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, M.; Roviglione, G.; Farulla, A.; Bertoglio, P.; Clarizia, R.; Viti, A.; Mautone, D.; Ceccarello, M.; Stepniewska, A.; Terzi, A.C. Minimally Invasive Treatment of Diaphragmatic Endometriosis: A 15-Year Single Referral Center’s Experience on 215 Patients. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 6807–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridogan, E.; Byrne, D. The British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy Endometriosis Centres Project. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2013, 76, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, S.; Smith, D.; Green, D.J. Barriers to a Timely Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Samartzis, N.; Kolovos, G.N.; Mareti, E.; Samartzis, E.P.; Eberhard, M.; Dinas, K.; Daniilidis, A. Treatment of Endometriosis: A Review with Comparison of 8 Guidelines. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culley, L.; Law, C.; Hudson, N.; Denny, E.; Mitchell, H.; Baumgarten, M.; Raine-Fenning, N. The Social and Psychological Impact of Endometriosis on Women’s Lives: A Critical Narrative Review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of endometriosis (years) | 37 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) at diagnosis * (kg/m2) | 23 kg/m2 |

| Age at first menstruation (years) | 14 |

| Age at first pregnancy (years) | 24 |

| Number of pregnancies | 2 |

| Number of live births | 2 |

| Number of miscarriages | 0 |

| Characteristics of menstrual cycle | Irregular cycles, 30/31 days, heavy, long (~7 days), very painful, sometimes bedridden since school age. |

| Previous gynecological surgeries | Curettage before first pregnancy in age of 23 |

| Comorbidities | Depression |

| Family history of endometriosis | None |

| Family history of other chronic diseases | Maternal grandmother—hypertension; Mother—malignant cervical and breast cancer. |

| Smoking | No |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes—occasional |

| Allergies | Inhalant—grass pollen, dust |

| Medications at the time of endometriosis diagnosis | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pietrzak, K.; Szablewska, A.W.; Pryba, B.; Gaworska-Krzemińska, A. From First Breathless Episode to Final Diagnosis and Treatment: A Case Report on Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176240

Pietrzak K, Szablewska AW, Pryba B, Gaworska-Krzemińska A. From First Breathless Episode to Final Diagnosis and Treatment: A Case Report on Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176240

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrzak, Katarzyna, Anna Weronika Szablewska, Bartosz Pryba, and Aleksandra Gaworska-Krzemińska. 2025. "From First Breathless Episode to Final Diagnosis and Treatment: A Case Report on Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176240

APA StylePietrzak, K., Szablewska, A. W., Pryba, B., & Gaworska-Krzemińska, A. (2025). From First Breathless Episode to Final Diagnosis and Treatment: A Case Report on Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176240