Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome and Arterial Hypertension—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

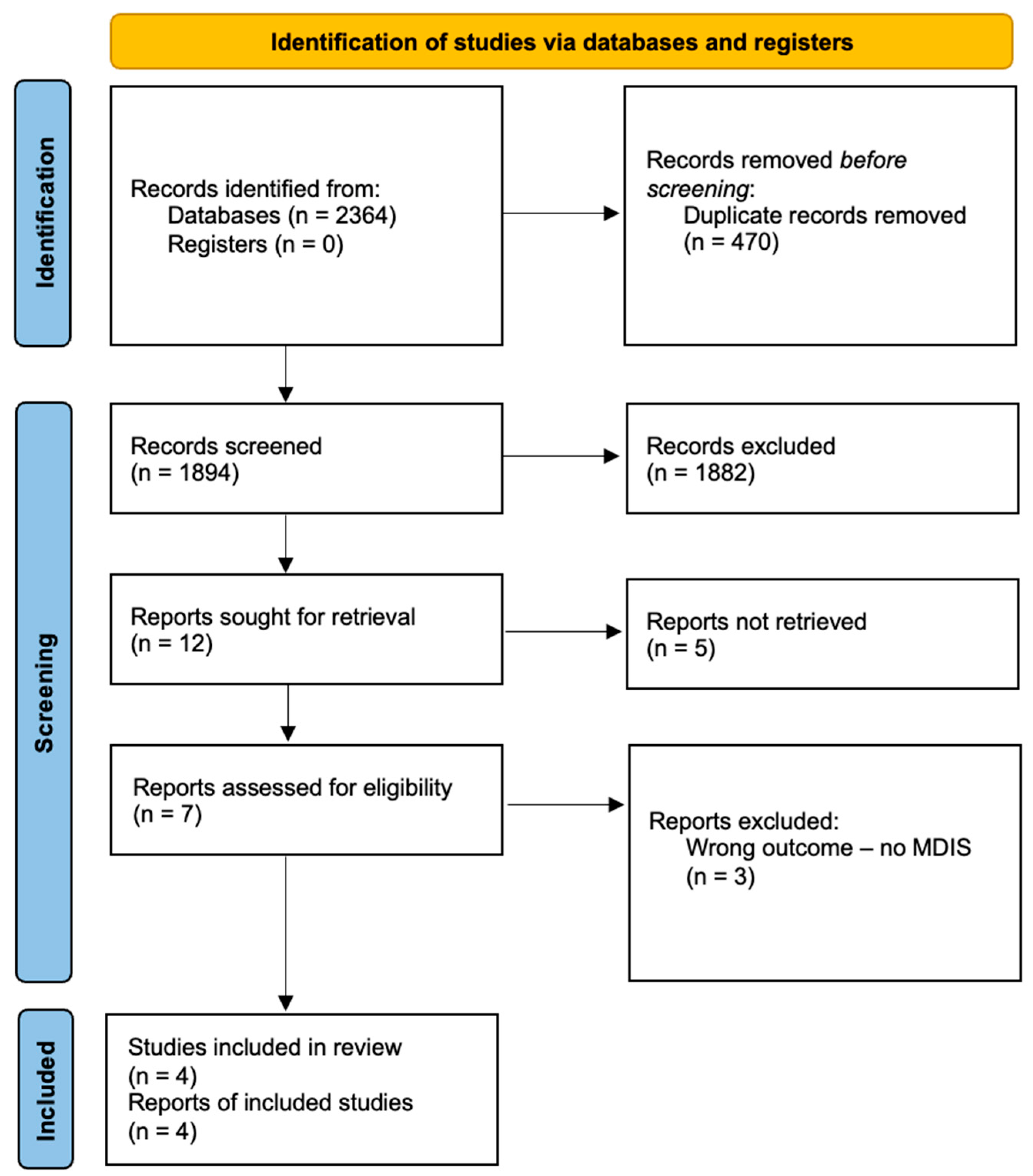

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Process

- Full-text original study assessing both drug intolerance and hypertension.

- Human subjects.

- At least 18 years of age.

- Outcomes include MDIS prevalence, type of adverse events or hypertension control.

- Other publication types (i.e., meta-analyses, reviews, case reports, conference reports).

- Specific drug trials.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Studies Characteristics

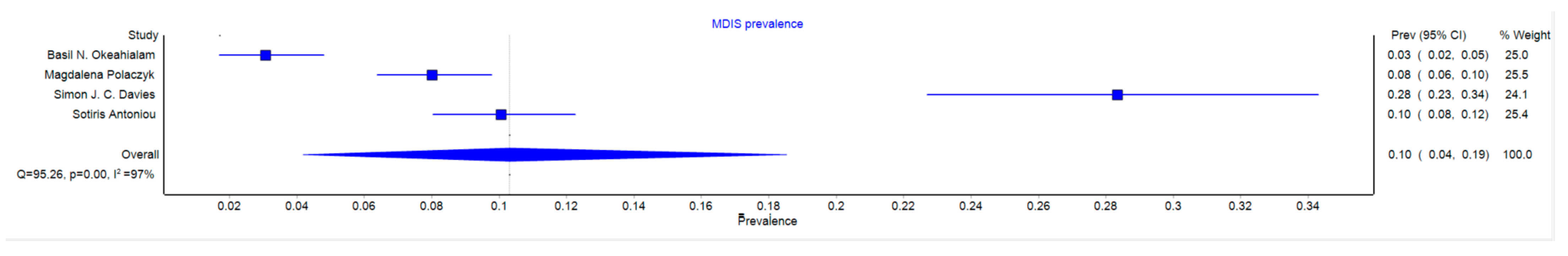

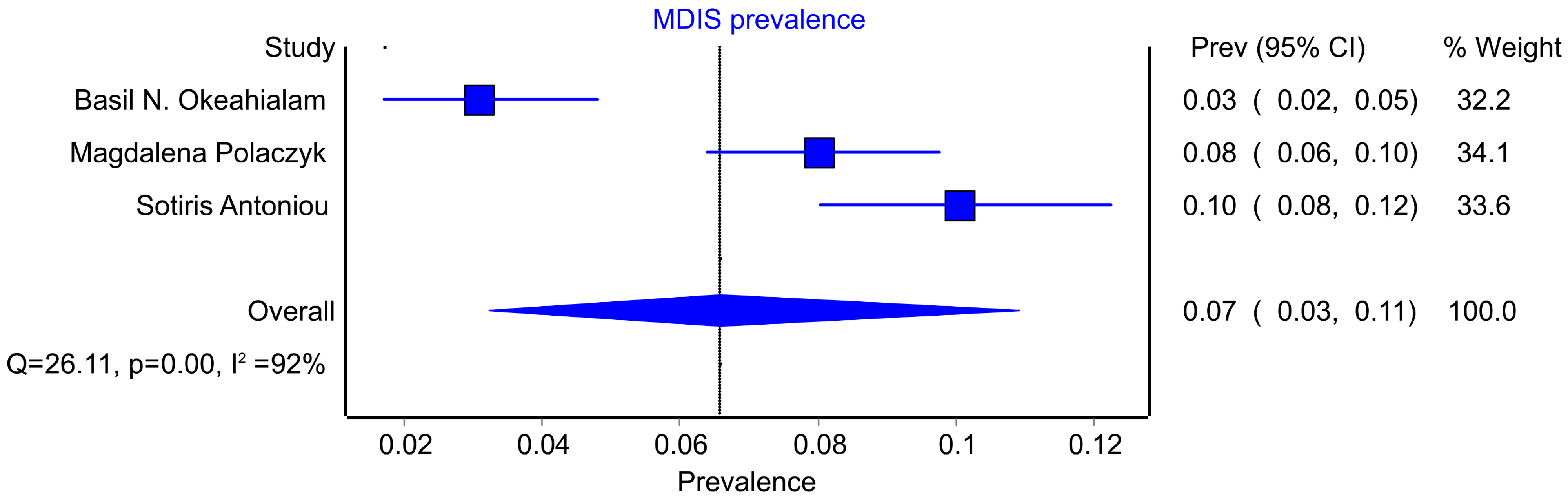

3.2. MDIS Prevalence

3.3. Adverse Drug Reactions Prevalence

3.4. MDIS Risk Factors

3.5. Hypertension Control

3.6. Intolerated Drugs

4. Discussion

4.1. Definitions of MDIS

4.2. Prevalence of MDIS

4.3. Adverse Drug Reactions

4.4. MDIS Risk Factors

4.5. Hypertension Control

4.6. Intolerated Drugs

4.7. Clinical Implications

4.8. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE-I | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ADR | Adverse drug reactions |

| ARB | Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| BB | Beta-blockers |

| CCB | Calcium channel blockers |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| MDIS | Multiple drug intolerance syndrome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Report on Hypertension; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lewington, S.; Clarke, R.; Qizilbash, N.; Peto, R.; Collins, R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002, 360, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohuet, G.; Struijker-Boudier, H. Mechanisms of target organ damage caused by hypertension: Therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 111, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insani, W.N.; Whittlesea, C.; Alwafi, H.; Man, K.K.C.; Chapman, S.; Wei, L. Prevalence of adverse drug reactions in the primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coca, A.; Whelton, S.P.; Camafort, M.; López-López, J.P.; Yang, E. Single-pill combination for treatment of hypertension: Just a matter of practicality or is there a real clinical benefit? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 126, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, E.; Ho, N.J. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and management. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012, 108, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Das, S.; Chengappa, K.G.; Xavier, A.S.; Selvarajan, S. Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome: An Underreported Distinct Clinical Entity. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 14, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaczyk, M.; Olszanecka, A.; Wojciechowska, W.; Rajzer, M.; Stolarz-Skrzypek, K. Multiple drug intolerance in patients with arterial hypertension: Prevalence and determining factors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009, 3, e123–e130. [Google Scholar]

- Palermiti, A.; Pappaccogli, M.; Rabbia, F.; D’Avolio, A.; Veglio, F. Multiple drug intolerance in antihypertensive patients: What is known and what is missing. J. Hypertens. 2024, 42, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.J.C.; Jackson, P.R.; Ramsay, L.E.; Ghahramani, P. Drug intolerance due to nonspecific adverse effects related to psychiatric morbidity in hypertensive patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses 2021. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Okeahialam, B.N. Multidrug intolerance in the treatment of hypertension: Result from an audit of a specialized hypertension service. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2017, 8, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, S.; Saxena, M.; Hamedi, N.; de Cates, C.; Moghul, S.; Lidder, S.; Kapil, V.; Lobo, M.D. Management of Hypertensive Patients with Multiple Drug Intolerances: A Single-Center Experience of a Novel Treatment Algorithm. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2016, 18, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagpal, P.K.; Alshareef, S.; Marriott, J.F.; Thirumala Krishna, M. Characterization, epidemiology and risk factors of multiple drug allergy syndrome and multiple drug intolerance syndrome: A systematic review. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2022, 12, e12190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, K.G.; Li, Y.; Acker, W.W.; Chang, Y.; Banerji, A.; Ghaznavi, S.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Zhou, L. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome and multiple drug allergy syndrome: Epidemiology and associations with anxiety and depression. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 73, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, H.M.; Hodson, J.; Thomas, S.K.; Coleman, J.J. Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome: A Large-Scale Retrospective Study. Drug Saf. 2014, 37, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaczyk, M.; Olszanecka, A.; Wojciechowska, W.; Rajzer, M.; Stolarz-Skrzypek, K. The occurrence of drug-induced side effects in women and men with arterial hypertension and comorbidities. Kardiol. Pol. 2022, 80, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Langen, J.; Van Hunsel, F.; Passier, A.; De Jong-Van Den Berg, L.; Van Grootheest, K. Adverse drug reaction reporting by patients in the Netherlands: Three years of experience. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.; Spaccapelo, L.; Gallesi, D.; Sternieri, E. Focus on headache as an adverse reaction to drugs. J. Headache Pain 2009, 10, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadley, R.M.; Armstrong, N.; Lee, Y.C.; Allen, A.; Kleijnen, J. Chronic diseases in the European Union: The prevalence and health cost implications of chronic pain. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2012, 26, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.A.; Carter, B.; Cushman, W.; Hamm, L. Thiazide and loop diuretics. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2011, 13, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Takuathung, M.; Sakuludomkan, W.; Khatsri, R.; Dukaew, N.; Kraivisitkul, N.; Ahmadmusa, B.; Mahakkanukrauh, C.; Wangthaweesap, K.; Onin, J.; Srichai, S.; et al. Adverse Effects of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 378 Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasri, A.; Hattle, M.; Koshiaris, C.; Dunnigan, A.; Paxton, B.; Fox, S.E.; Smith, M.; Archer, L.; Levis, B.; Payne, R.A.; et al. Association between antihypertensive treatment and adverse events: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 372, n189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dhopeshwarkar, N.; Blumenthal, K.G.; Goss, F.; Topaz, M.; Slight, S.P.; Bates, D.W. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy 2016, 71, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, T.; Nucera, E.; Boccascino, R.; Romeo, P.; Biagini, G.; Buonomo, A.; Colagiovanni, A.; Pecora, V.; Aruanno, A.; Rizzi, A.; et al. Allergy and psychologic evaluations of patients with multiple drug intolerance syndrome. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2012, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengul, S.; Akpolat, T.; Erdem, Y.; Derici, U.; Arici, M.; Sindel, S.; Karatan, O.; Turgan, C.; Hasanoglu, E.; Caglar, S.; et al. Changes in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in Turkey from 2003 to 2012. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorobantu, M.; Tautu, O.F.; Dimulescu, D.; Sinescu, C.; Gusbeth-Tatomir, P.; Arsenescu-Georgescu, C.; Mitu, F.; Lighezan, D.; Pop, C.; Babes, K.; et al. Perspectives on hypertension’s prevalence, treatment and control in a high cardiovascular risk East European country: Data from the SEPHAR III survey. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalá-López, F.; Sanfélix-Gimeno, G.; García-Torres, C.; Ridao, M.; Peiró, S. Control of arterial hypertension in Spain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 76 epidemiological studies on 341 632 participants. J. Hypertens. 2012, 30, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojangba, T.; Boamah, S.; Miao, Y.; Guo, X.; Fen, Y.; Agboyibor, C.; Yuan, J.; Dong, W. Comprehensive effects of lifestyle reform, adherence, and related factors on hypertension control: A review. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 25, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.T.; Dolan, J.; Bazzano, L.A.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Krousel-Wood, M.; Rubinstein, A.; Irazola, V.; Beratarrechea, A.; Poggio, R.; et al. Comprehensive approach for hypertension control in low-income populations: Rationale and study design for the hypertension control program in argentina. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 348, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Khan, H.; Heydon, E.; Shroufi, A.; Fahimi, S.; Moore, C.; Stricker, B.; Mendis, S.; Hofman, A.; Mant, J.; et al. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: A meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2940–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakiris, M.A.; Sawan, M.; Hilmer, S.N.; Awadalla, R.; Gnjidic, D. Prevalence of adverse drug events and adverse drug reactions in hospital among older patients with dementia: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Number of Patients | Number of Patients with MDIS | Number of Patients Without MDIS | Number of Patients with Single Drug Intolerance | MDIS Definition Included in the Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okeahialam | 2017 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | 489 | 15 | 474 | - | Intolerance to ≥3 drugs with no clear immunological mechanism |

| Polaczyk | 2023 | Poland | Cross-sectional study | 1000 | 80 | 920 | 320 | ADRs to ≥3 different classes of drugs |

| Davies | 2003 | United Kingdom | Case–control study | 233 | 66 | 167 | 52 | Intolerance to 2 or more antihypertension drugs |

| Antoniou | 2016 | United Kingdom | Case–control study | 786 | 79 | 707 | - | ADRs to ≥3 drugs of any class without a known immunological mechanism |

| ADR | Pooled Prevalence [%] | 95% CI for Pooled Prevalence | I2 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrocyte imbalance | 2.50 | 0.04–7.39 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Hypotension | 30.00 | 20.4–40.55 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Cough | 33.94 | 8.73–64.44 | 91.42 |

| Edema | 38.86 | 2.95–82.45 | 95.62 |

| Bradycardia | 11.25 | 5.12–19.23 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Skin lesions | 36.71 | 11.04–66.57 | 91.09 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 26.25 | 19.74–33.32 | 0 |

| Allergic reactions | 66.25 | 55.47–76.25 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Bleeding | 5.00 | 1.1–11.08 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Abnormal laboratory tests results | 1.80 | 0–5.29 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Muscular pain | 4.51 | 1.09–9.77 | 0 |

| Headache | 71.47 | 56.5–84.44 | 32.51 |

| Vasomotor reactions | 26.26 | 0–70.24 | 89.42 |

| Palpitations | 18.77 | 2.23–43.5 | 71.05 |

| Sore or dry mouth/throat | 7.58 | 2.2–15.42 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Tiredness | 37.11 | 0–100 | 95.67 |

| Wheeze | 16.57 | 6.11–30.41 | 36.37 |

| Dyspnea | 12.13 | 5.19–21.25 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Sleep disturbances | 7.64 | 2.58–14.81 | 2.51 |

| Urinary frequency | 15.16 | 7.38–24.94 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Gout | 12.13 | 5.19–21.25 | Only one study with this outcome |

| Impotence | 4.55 | 0.58–11.21 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Gynecomastia | 3.04 | 0.05–8.92 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Dizziness | 16.26 | 4.72–32.19 | 47.35 |

| Bad feeling | 59.98 | 33.86–83.65 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Pain (other than headache) | 53.08 | 0–100 | 98.46 |

| Tinnitus | 20.06 | 3.05–44.62 | Only one study with this ADR |

| Risk Factor | OR or Difference (Non-MDIS vs. MDIS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okeahialam | Polaczyk | Antoniou | Davies | |

| Female sex | 55% vs. 67% | OR = 2.05 * | 13% vs. 40% * | 50% vs. 67% * |

| Older age | - | OR = 1.00 | 47 vs. 66 years * | 59 vs. 64 years * |

| Disease duration | - | Median: 10 vs. 15 years * | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal tract diseases | - | OR = 2.33 * | GERD: 42% vs. 10% | - |

| Psychiatric diseases | - | OR = 1.46 | Anxiety disorders: 3% vs. 16% | in text |

| Rheumatoid diseases | - | OR = 3.14 * | - | - |

| Endocrine diseases | - | OR = 2.09 * | - | - |

| Respiratory system diseases | - | OR = 2.14 * | - | - |

| Drug Class | Okeahialam | Polaczyk |

|---|---|---|

| ACE-I | 33.33% | 20.00% |

| BB | 73.33% | 8.75% |

| ARB | 60.00% | 8.75% |

| CCB | 73.33% | 15.00% |

| Diuretics | 80.00% | 8.75% |

| Antiplatelets | NR | 12.5% |

| Anticoagulants | NR | 3.75% |

| Statins | NR | 8.75% |

| Antibiotics | NR | 46.25% |

| Analgesics | 46.67% | 43.75% |

| Dihydroergotoxine | 13.33% | NR |

| Reserpine | 13.33% | NR |

| Alpha blocker | 6.67% | NR |

| Methyldopa | 13.33% | NR |

| MRA | 6.67% | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rusinek, J.; Tyjas, K.; Ziółek, W.; Rajzer, M.; Stolarz-Skrzypek, K. Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome and Arterial Hypertension—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176218

Rusinek J, Tyjas K, Ziółek W, Rajzer M, Stolarz-Skrzypek K. Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome and Arterial Hypertension—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176218

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusinek, Jakub, Kinga Tyjas, Wiktoria Ziółek, Marek Rajzer, and Katarzyna Stolarz-Skrzypek. 2025. "Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome and Arterial Hypertension—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176218

APA StyleRusinek, J., Tyjas, K., Ziółek, W., Rajzer, M., & Stolarz-Skrzypek, K. (2025). Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome and Arterial Hypertension—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176218