Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome (PROMs) Measures in Diabetic Foot Disease Management—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

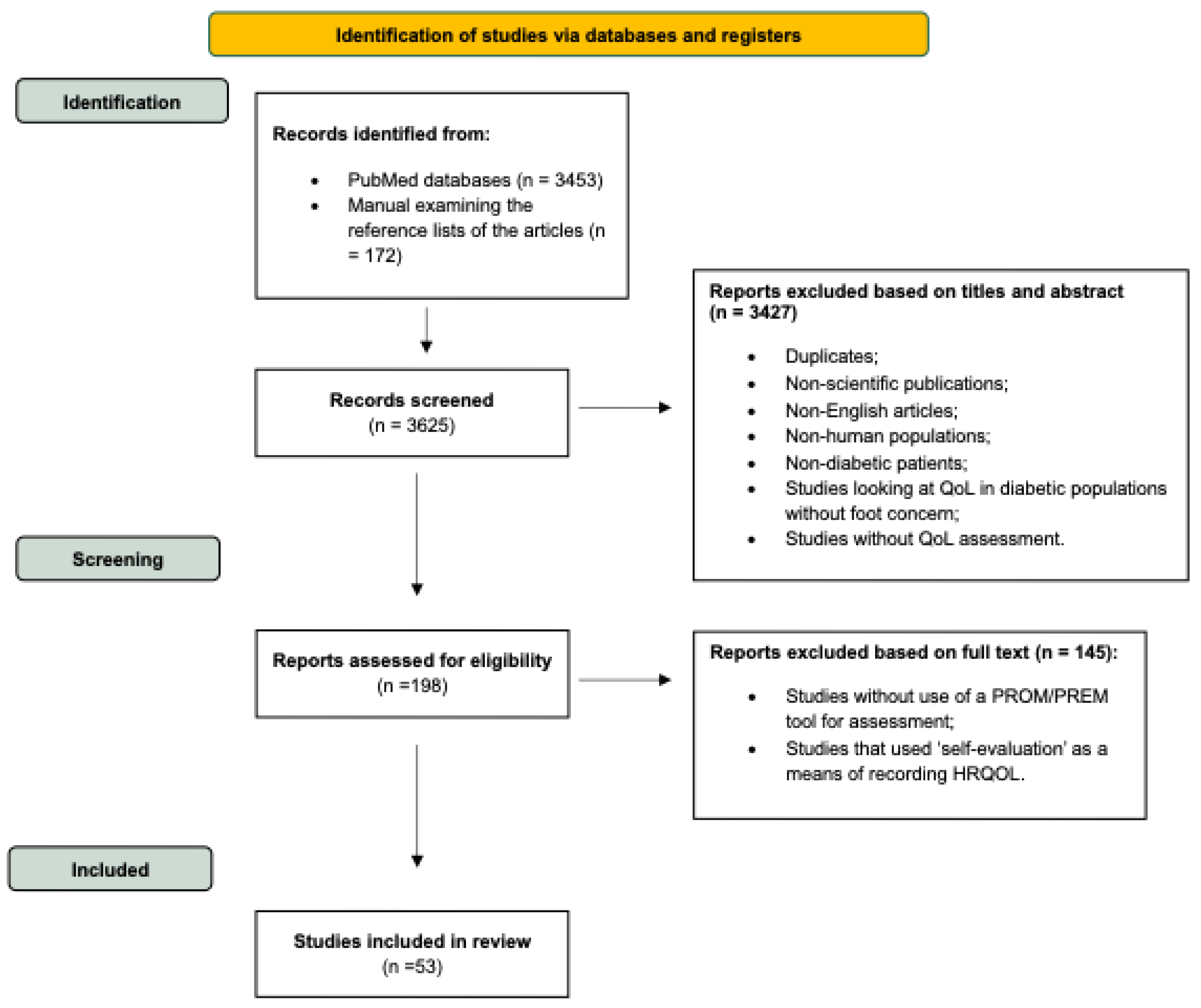

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaper, N.C.; van Netten Jaap, J.; Apelqvist, J.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Game, F.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Senneville, E. IWGDF Editorial Board Practical Guidelines on the Prevention and Management of Diabetes-Related Foot Disease (IWGDF 2023 Update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoropoulou, P.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Jude, E.B.; Tentolouris, N. Diabetic Foot Infections: An Update in Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicale, R.; Cipollaro, L.; Esposito, S.; Maffulli, N. An Evidence Based Narrative Review on Treatment of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis. Surgeon 2020, 18, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyk, D.F. The Diabetic Foot: Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Treatment. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 31, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Fernández-Torres, R.; Formosa, C.; Gatt, A.; Pérez-Panero, A.J.; Pérez-Belloso, A.J.; Martínez-Barrios, F.J.; González-Sánchez, M. Development and Validation of a New Questionnaire for the Assessment of Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease: The Diabetic Foot Questionnaire (DiaFootQ). Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wukich, D.K.; Raspovic, K.M. Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease: Why Is It Important and How Can We Improve? The 2017 Roger E. Pecoraro Award Lecture. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Collado, À.; Hernández-Martínez-Esparza, E.; Zabaleta-Del-Olmo, E.; Urpí-Fernández, A.-M.; Santesmases-Masana, R. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Quality of Life in People Affected by Diabetic Foot: A Psychometric Systematic Review. Value Health 2022, 25, 1602–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarić, V.; Svirčević, V.; Bijuk, R.; Zupančič, V. Chronic Complications of Diabetes and Quality of Life. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. WHOQOL Group The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment: Psychometric Properties and Results of the International Field Trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, F.R.A.; Peach, G.; Price, P.; Thompson, M.M.; Hinchliffe, R.J. Measures of Health-Related Quality of Life in Diabetes-Related Foot Disease: A Systematic Review. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Delgado, J.; Guilabert, M.; Mira-Solves, J. Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures in People Living with Diabetes: A Scoping Review of Instruments. Patient 2021, 14, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, P.R.; Rajan, S.; Sudeepthi, B.L.; Abdul Nazir, C.P. Patient-Reported Outcomes: A New Era in Clinical Research. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2011, 2, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, A.; Boland, V.; Dowling, M. Patient-Reported Outcome and Experience Measures in Advanced Nursing Practice: What Are Key Considerations for Implementation and Optimized Use? Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 40, 151632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shunmuga Sundaram, C.; Campbell, R.; Ju, A.; King, M.T.; Rutherford, C. Patient and Healthcare Provider Perceptions on Using Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) in Routine Clinical Care: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Burt, J.; Roland, M. Measuring Patient Experience: Concepts and Methods. Patient 2014, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeravini, E.; Tentolouris, A.; Tentolouris, N.; Jude, E.B. Advancements in Improving Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Living with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 13, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sánchez, E.; Santamaría-Peláez, M.; Benito Figuerola, E.; Carballo García, M.J.; Chico Hernando, M.; García García, J.M.; González-Bernal, J.J.; González-Santos, J. Comparison of SF-36 and RAND-36 in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Reliability Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnarson Tennvall, G.; Apelqvist, J. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Foot Ulcers. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2000, 14, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Gibby, O.; Phillips, C.; Price, P.; Tyrrell, W. The Health Status of diabetic patients Receiving Orthotic Therapy. Qual. Life Res. 2000, 9, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willrich, A.; Pinzur, M.; McNeil, M.; Juknelis, D.; Lavery, L. Health Related Quality of Life, Cognitive Function, and Depression in diabetic patients with Foot Ulcer or Amputation. A Preliminary Study. Foot Ankle Int. 2005, 26, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valensi, P.; Girod, I.; Baron, F.; Moreau-Defarges, T.; Guillon, P. Quality of Life and Clinical Correlates in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Metab. 2005, 31, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuurs-Franssen, M.H.; Huijberts, M.S.P.; Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman, A.C.; Willems, J.; Schaper, N.C. Health-Related Quality of Life of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Patients and Their Caregivers. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 1906–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, D.; Trepman, E.; Sloan, J.; Guse, L.; Strain, L.A.; McIntyre, J.; Embil, J.M. Quality of Life of Adults with Unhealed and Healed Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Foot Ankle Int. 2006, 27, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribu, L.; Rustøen, T.; Birkeland, K.; Hanestad, B.R.; Paul, S.M.; Miaskowski, C. The Prevalence and Occurrence of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Pain and Its Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life. J. Pain 2006, 7, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribu, L.; Hanestad, B.R.; Moum, T.; Birkeland, K.; Rustoen, T. Health-Related Quality of Life among Patients with Diabetes and Foot Ulcers: Association with Demographic and Clinical Characteristics. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2007, 21, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribu, L.; Hanestad, B.R.; Moum, T.; Birkeland, K.; Rustoen, T. A Comparison of the Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers, with a Diabetes Group and a Nondiabetes Group from the General Population. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutoille, D.; Féraille, A.; Maulaz, D.; Krempf, M. Quality of Life with Diabetes-Associated Foot Complications: Comparison between Lower-Limb Amputation and Chronic Foot Ulceration. Foot Ankle Int. 2008, 29, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakarinen, T.-K.; Laine, H.-J.; Mäenpää, H.; Mattila, P.; Lahtela, J. Long-Term Outcome and Quality of Life in Patients with Charcot Foot. Foot Ankle Surg. 2009, 15, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkley, K.; Stahl, D.; Chalder, T.; Edmonds, M.E.; Ismail, K. Quality of Life in People with Their First Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2009, 99, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, E.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L.; Martínez-Hernández, D.; Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Beneit-Montesinos, J.V.; González-Jurado, M.A. Impact of Diabetic Foot Related Complications on the Health Related Quality of Life (HRQol) of Patients—A Regional Study in Spain. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2011, 10, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meneses, L.C.; Blanes, L.; Francescato Veiga, D.; Carvalho Gomes, H.; Masako Ferreira, L. Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Esteem in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Results of a Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2011, 57, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.-P.; Ribu, L.; Bernklev, T.; Moum, B.A. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Non-Complicated Diabetes Patients May Be an Effective Parameter to Assess Patients at Risk of a More Serious Disease Course: A Cross-Sectional Study of Two Diabetes Outpatient Groups. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjari, M.; Safari, S.; Shokoohi, M.; Safizade, H.; Rashidinezhad, H.; Mashrouteh, M.; Alavi, A. A Cross-Sectional Study in Kerman, Iran, on the Effect of Diabetic Foot Ulcer on Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2011, 10, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Ting, X.; Minjie, W.; Yemin, C.; Xiqiao, W.; Yuzhi, J.; Ming, T.; Weida, W.; Peifen, Q.; Shuliang, L. The Investigation of Demographic Characteristics and the Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers at First Presentation. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2012, 11, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Alzahrani, H.; Sehlo, M.G. The Impact of Religious Connectedness on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siersma, V.; Thorsen, H.; Holstein, P.E.; Kars, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.B.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Jirkovska, A.; et al. Importance of Factors Determining the Low Health-Related Quality of Life in People Presenting with a Diabetic Foot Ulcer: The Eurodiale Study. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fejfarová, V.; Jirkovská, A.; Dragomirecká, E.; Game, F.; Bém, R.; Dubský, M.; Wosková, V.; Křížová, M.; Skibová, J.; Wu, S. Does the Diabetic Foot Have a Significant Impact on Selected Psychological or Social Characteristics of Patients with Diabetes Mellitus? J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 371938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.; Sharpe, L.; Blaszczynski, A. The Psychosocial Impact Associated with Diabetes-Related Amputation. Diabet. Med. 2014, 31, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspovic, K.M.; Wukich, D.K. Self-Reported Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetes: A Comparison of Patients with and without Charcot Neuroarthropathy. Foot Ankle Int. 2014, 35, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raspovic, K.M.; Wukich, D.K. Self-Reported Quality of Life and Diabetic Foot Infections. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014, 53, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siersma, V.; Thorsen, H.; Holstein, P.E.; Kars, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.B.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Jirkovská, A.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Predicts Major Amputation and Death, but Not Healing, in People with Diabetes Presenting with Foot Ulcers: The Eurodiale Study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspovic, K.M.; Hobizal, K.B.; Rosario, B.L.; Wukich, D.K. Midfoot Charcot Neuroarthropathy in Patients with Diabetes: The Impact of Foot Ulceration on Self-Reported Quality of Life. Foot Ankle Spec. 2015, 8, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, M.S.; Thomas, R.R.; Unnikrishnan, M.K.; Vijayanarayana, K.; Rodrigues, G.S. Impact of Diabetic Foot Ulcer on Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 28, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoban, C.; Sareen, J.; Henriksen, C.A.; Kuzyk, L.; Embil, J.M.; Trepman, E. Mental Health Issues Associated with Foot Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. Foot Ankle Surg. 2015, 21, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, R.T.; Shen, B.-J.; Campbell, L.; Lamont, P.J.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Peyrot, M.; Kirsner, R.S.; Vileikyte, L. Role and Determinants of Adherence to Off-Loading in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Healing: A Prospective Investigation. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedras, S.; Carvalho, R.; Pereira, M.G. Quality of Life in Portuguese Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer Before and After an Amputation Surgery. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemcová, J.; Hlinková, E.; Farský, I.; Žiaková, K.; Jarošová, D.; Zeleníková, R.; Bužgová, R.; Janíková, E.; Zdzieblo, K.; Wiraszka, G.; et al. Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer in Visegrad Countries. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siersma, V.; Thorsen, H.; Holstein, P.E.; Kars, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.B.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Jirkovská, A.; et al. Diabetic Complications Do Not Hamper Improvement of Health-Related Quality of Life over the Course of Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers—The Eurodiale Study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, K.; Saleptsis, V.; Athanasoulas, A.; Karathanos, C.; Bargiota, A.; Chan, P.; Giannoukas, A.D. Factors Associated with Ulcer Healing and Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Angiology 2017, 68, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickwell, K.; Siersma, V.; Kars, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jirkovská, A.; Jude, E.B.; Mauricio, D.; et al. Minor Amputation Does Not Negatively Affect Health-Related Quality of Life as Compared with Conservative Treatment in Patients with a Diabetic Foot Ulcer: An Observational Study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspovic, K.M.; Ahn, J.; La Fontaine, J.; Lavery, L.A.; Wukich, D.K. End-Stage Renal Disease Negatively Affects Physical Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Complications. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2017, 16, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, D.K.; Ahn, J.; Raspovic, K.M.; La Fontaine, J.; Lavery, L.A. Improved Quality of Life After Transtibial Amputation in Patients with Diabetes-Related Foot Complications. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2017, 16, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedras, S.; Carvalho, R.; Pereira, M.G. Predictors of Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer: The Role of Anxiety, Depression, and Functionality. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Del Core, M.A.; Wukich, D.K.; Liu, G.T.; Lalli, T.; VanPelt, M.D.; La Fontaine, J.; Lavery, L.A.; Raspovic, K.M. Scoring Mental Health Quality of Life With the SF-36 in Patients With and Without Diabetes Foot Complications. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2018, 17, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Core, M.A.; Ahn, J.; Wukich, D.K.; Liu, G.T.; Lalli, T.; VanPelt, M.D.; Raspovic, K.M. Gender Differences on SF-36 Patient-Reported Outcomes of Diabetic Foot Disease. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2018, 17, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosaimi, F.D.; Labani, R.; Almasoud, N.; Alhelali, N.; Althawadi, L.; AlJahani, D.M. Associations of Foot Ulceration with Quality of Life and Psychosocial Determinants among Patients with Diabetes; a Case-Control Study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2019, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunkaew, S.; Fernandez, R.; Sim, J. Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Care Management Among People with Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Northern Thailand. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819825751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrub, A.A.; Hyassat, D.; Khader, Y.S.; Bani-Mustafa, R.; Younes, N.; Ajlouni, K. Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life among Jordanian Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 4706720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, M.M.; Igland, J.; Smith-Strøm, H.; Østbye, T.; Tell, G.S.; Skeie, S.; Cooper, J.G.; Peyrot, M.; Graue, M. Effect of a Telemedicine Intervention for Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers on Health, Well-Being and Quality of Life: Secondary Outcomes from a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial (DiaFOTo). BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, M.S.; Thenmozhi, P.; Vijayaragavan, R. Impact of Chronic Wound on Quality of Life among Diabetic Foot Ulcer Patients in a Selected Hospital of Guwahati, Assam, India. Ayu 2020, 41, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikandrioti, M.; Vasilopoulos, G.; Koutelekos, I.; Panoutsopoulos, G.; Gerogianni, G.; Babatsikou, F.; Zartaloudi, A.; Toulia, G. Quality of Life in Diabetic Foot Ulcer: Associated Factors and the Impact of Anxiety/Depression and Adherence to Self-Care. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2020, 19, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.; Gu, D.-F.; Cao, H.; Yuan, Q.-F.; Dong, Z.-X.; Yu, D.; Shen, X.-M. Impacts of Psychological Resilience on Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 5610–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinboldt-Jockenhöfer, F.; Babadagi, Z.; Hoppe, H.-D.; Risse, A.; Rammos, C.; Cyrek, A.; Blome, C.; Benson, S.; Dissemond, J. Association of Wound Genesis on Varying Aspects of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Different Types of Chronic Wounds: Results of a Cross-Sectional Multicentre Study. Int. Wound J. 2021, 18, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juzwiszyn, J.; Łabuń, A.; Tański, W.; Szymańska-Chabowska, A.; Zielińska, D.; Chabowski, M. Acceptance of Illness, Quality of Life and Nutritional Status of Patients after Lower Limb Amputation Due to Diabetes Mellitus. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 79, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, B.M.; van Netten, J.J.; Aan de Stegge, W.B.; Busch-Westbroek, T.E.; Bus, S.A. Health-Related Quality of Life and Associated Factors in People with Diabetes at High Risk of Foot Ulceration. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2022, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpierre, T.; McCormick, K.; Backhouse, M.R.; Bruce, J.; Cherry, L. The Short-Term Impact of Non-Removable Offloading Devices on Quality of Life in People with Recurrent Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. Wound Care 2023, 32, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, Y.H.; Mohammed, M.; Hamid, S.; Mohamedahmed, W.; Ahmed, O. Impact of Diabetic Foot Ulcer on the Health-Related Quality of Life of People living with diabetes in Khartoum State. Cureus 2024, 16, e52813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.; Ward, L.; Jensen, S.; Sagoo, M.; Charles, D.; Mann, R.; Nghiem, S.; Finch, J.; Gavaghan, B.; McBride, L.-J.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in People with Different Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcer Health States: A Cross-Sectional Study of Healed, Non-Infected, Infected, Hospitalised and Amputated Ulcer States. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 207, 111061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Afonso, F.J.; García-Madrid, M.; García-Morales, E.; López-Moral, M.; Molines-Barroso, R.J.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L. Health-Related Quality of Life among Spanish Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer According to Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale—Short Form. J. Tissue Viability 2024, 33, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.; Harding, K. Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule: The Development of a Condition-Specific Questionnaire to Assess Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Wounds of the Lower Limb. Int. Wound J. 2004, 1, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abetz, L.; Sutton, M.; Brady, L.; McNulty, P.; Gagnon, D.D. The Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale (DFS): A Quality of Life Instrument for Use in Clinical Trials. Pract. Diab Int. 2002, 19, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Kaizer, U.A.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Rodrigues, R.C.M.; Cornélio, M.E.; de Melo Lima, M.H.; São-João, T.M. Measurement Properties and Factor Analysis of the Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale-Short Form (DFS-SF). Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and Preliminary Testing of the New Five-Level Version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.L.; Hutt, D.M.; Wukich, D.K. Validity of the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) in Diabetes Mellitus. Foot Ankle Int. 2009, 30, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vileikyte, L.; Peyrot, M.; Bundy, C.; Rubin, R.R.; Leventhal, H.; Mora, P.; Shaw, J.E.; Baker, P.; Boulton, A.J.M. The Development and Validation of a Neuropathy- and Foot Ulcer-Specific Quality of Life Instrument. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2549–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, R.D.; Morales, L.S. The RAND-36 Measure of Health-Related Quality of Life. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E. SF-36 Health Survey Update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 3130–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Bian, J.; Guo, Y. Evaluating the Reliability and Validity of SF-8 with a Large Representative Sample of Urban Chinese. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C.; Baade, K.; Debus, E.S.; Price, P.; Augustin, M. The “Wound-QoL”: A Short Questionnaire Measuring Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Wounds Based on Three Established Disease-Specific Instruments. Wound Repair. Regen. 2014, 22, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Ghahramanloo, A.; Soltani-Kermanshahi, M.; Mansori, K.; Khazaei-Pool, M.; Sohrabi, M.; Baradaran, H.R.; Talebloo, Z.; Gholami, A. Comparison of SF-36 and WHOQoL-BREF in Measuring Quality of Life in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Cervera-Garvi, P.; Ramos-Petersen, L.; Chicharro-Luna, E.; Gijon-Nogueron, G. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Foot and Ankle Pathologies: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Panero, A.J.; Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Fernández-Torres, R.; Formosa, C.; Gatt, A.; Gónzalez-Sánchez, M. Diabetic Foot Disease: A Systematic Literature Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 3395–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.; Sharma, J.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö. When the patient is the expert: Measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Design | Study Aims | Study Results | PROMs Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ragnarson Tenvall, Apelqvist Sweden, 2000 [19] | Cross-sectional 310 patients, 4 groups | To assess QoL in people living with diabetes with ulcer, with healed ulcer and in those with amputation. | Current ulcers and major amputation have a negative impact on QoL and reduce EQ-5D index compared to patients who heal primarily without amputations or who undergo minor amputations. | EQ-5D-3L |

| Davies et al. U.K, 2000 [20] | Case-control 280 patients, 4 groups | To compare the health status of a group of people living with diabetes receiving orthotic therapy with a group not receiving it. | Orthotic therapy resulted in a statistically significant increase in all SF-36 scores, both physical and mental, at 6- and 12-month assessment compared to the comparison group in which a worsening of QoL was observed | SF-36 |

| Willrich et al. USA, 2005 [21] | Preliminar—pilot study 60 patients, 3 groups | To determine if there is a correlation between podalic complications such as DFU, infections, NOA (neuro-osteo-arthropathy), amputations and cognitive impairment or depression. | DFU, Charcot NOA, and amputation have significant negative impact on QoL at SF-36 scores without demonstration of cognitive impairment or depression. | SF-36 |

| Valensi et al. France, 2005 [22] | Cross-sectional- observational 355 patients, 2groups | To compare QoL in DM patients with/without DFU and determine specific pathology factors influencing QoL in patients with DFU. | DFU patients have lower SF-36 scores compared to those without foot ulcers. Worse DFS scores are found for higher Wagner grades, long-standing ulcers, and multiple ulcers. Age is associated with lower DFS scores for the domains of daily activity and dependence of DFS. | SF-36 DFS |

| Nabuurs-Franssen et al. Holland, 2005 [23] | Prospective-multicenter 294 patients and 153 caregivers | To determine the impact of ulcer healing on the QoL of people living with diabetes and their caregivers. | Patients with healing ulcers have higher QoL scores than patients with persistent ulcers both 20 weeks after baseline (T1) and 12 weeks after T1 (T2), particularly for the SF-36 domains of physical and social function, physical role, and the physical summary score. The caregiver scores of the emotional role subscale improve for those of patients who heal compared to those for whom the ulcer persists, especially in T2. | SF-36 |

| Goodridge et al. Canada, 2006 [24] | Cross-sectional- comparative 104 patients, 2 groups | Evaluate QoL in patients with healed and non-healed DFUs. | Patients with non-healed ulcers have lower PCS (physical component summary score) score on SF-12 than those with healed ulcer. No differences are observed for MCS (mental component summary score) score between the two groups. Regarding the CWIS (Cardiff wound impact schedule) scores, patients with non-healed ulcers result frustrated and anxious with low well-being component score. | SF-12 CWIS |

| Ribu et al. Norway, 2006 [25] | Observational 127 DFU patients | To describe the prevalence and occurrence of DFU-associated pain and the impact on HRQL using generic and disease-specific instruments. | 75% of DFU patients’ sample have pain during walking/standing and/or in the night. Patients who reported DFU related pain show low score in all DFS and SF-36 subscales. | SF-36 DFS (Diabetic Foot ulcer scale) |

| Ribu et al. Norway, 2007 [26] | Cross-sectional 127 DFU patients | To describe sociodemographic variables, clinical characteristics, and treatment factors in patients with diabetic foot ulcer and explore the association between these factors and patients’ QOL. | Clinical variables with a negative effect on SF-36 score are BMI (body mass index) < 25 kg/m2, nephropathy, an ABPI (ankle brachial pressure index) value < 0.9, CRP (C reactive protein) levels > 10 mg/L and ulcer size greater than 5 cm2. No significant influence of demographic variables on QoL was found in the selected patient sample. | SF-36 |

| Ribu et al. Norway, 2007 [27] | Cross-sectional 127 DFU patients—221 DM patients—5903 general population | To describe HRQL in patients with DFU by comparing their HRQL with that of a general population sample without diabetes and a subgroup with diabetes and to examine differences between groups based on sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors. | DFU patients scored significantly lower in all SF-36 domains compared to the population living with diabetes samples and also compared to the general population sample. BMI was higher for DFU patients compared to the other population samples and most DFU patients lived alone compared to the other two population samples. | SF-36 |

| Boutoille et al. France, 2008 [28] | Case-control-retrospective 34 patients, 2 groups | Understanding the influence of amputation on the physical and social aspects of QoL in patients with diabetic foot. | Patients with DFU reported lower score for the items “Bodily pain” and “Role Physical” of SF-36 than the amputation group. The global scores of SF-36 were poor in both groups. | SF-36 |

| Pakarinen et al. Finland, 2009 [29] | Cross-sectional-follow up 29 patients | To evaluate long-term effects and QoL of patients with Charcot after a minimum of 5 years of follow-up. | 67% of patients with Charcot foot had one ulcer during the follow up period and 40% of patients had an ulcer once or more. 50% of patients underwent surgery. The functional outcome was better for patients who were diagnosed within 3 months. Patients with Charcot foot reported lower SF-36 scores compared to general population and to chronically ill population, particularly for role physical, role emotional and social functioning domains; These scores are reduced for patients with walking ability of less than 500 m. | SF 36 |

| Winkley et al. U.K., 2009 [30] | Cohort-Prospective 253 patients | To prospectively describe changes over 18 months in QoL of patients with DM and newly discovered ulcer. | At 18-months FU (follow up) patients with a first DFU reported a decrease in SF-36 scores for physical functioning, mental health and general health domains. A significant decrease in MCS scores was observed in patients who did not heal and in those who had recurrence of ulcers.-Non-significant reduction was observed in amputated patients. | SF-36 |

| Garcia-Morales et al. Spain, 2011 [31] | Comparative-prospective 421 patients, 2 groups | To determine the impact of etiological and pathogenetic factors of diabetic foot on various aspects of QoL in the Spanish region of Gran Canaria. | A statistically significant difference in the overall score of SF-36 between group 1 (no ulcer) and group 2 (ulcer); the lower scores for group 2 were recorded in physical functions, physical role limitation and vitality domains. Neuropathy and poor metabolic control significantly reduce patients’ QoL. Patients with an ulcer for less than 2 months had higher QOL than those with a lesion for more than 3. | SF-36 |

| De Meneses et al. Brasil, 2011 [32] | Cross-sectional comparative 35 patients, 2 groups (DFU—NO DFU) | Assessing HRQoL and self-esteem in patients with DFU. | Patients with DFU had lower SF-36 scores than those without foot ulcer, particularly for physical functioning, social functioning, and emotional domains. No differences regarding self esteem between groups were observed. Women on average had a higher QOL score than men. | SF-36 |

| Jelsness-Jørgensen et al. Norway, 2011 [33] | Cross-sectional 157 patients, 2 groups (DM no DFU—DM + DFU) | Describe HRQOL in DM patients without DFU and identify sociodemographic and/or clinical variables that significantly influence HRQOL and investigate DFU effects on HRQOL, comparing patients with and without DFU. | Patients with DFU have more comorbidities than those without, especially cardiovascular (6 times more at risk). Patients with diabetic foot ulcer had reduced scores in 7 out of 8 domains of SF-36 especially in physical domains. | SF-36 |

| Sanjari et al. Iran, 2011 [34] | Cross-sectional 132 patients, 2 groups | To evaluate the factors influencing QoL of Iranian patients with DM and the effect of DFU on QoL in patients with DM. | DFU patients reported lower SF-36 scores in physical functioning, physical, bodily pain, social functioning, and emotional role domains than patients without DFU. Women had lower overall QoL, lower scores in physical functioning dimension and higher body pain. | SF-36 |

| Yao et al. China, 2012 [35] | Observational perspective 131 patients DFU | To investigate the demographic, lesion and QoL characteristics of patients with DM at first visit for new ulcer, the influence of diabetic foot and its severity on the QoL of patients, and the influence of ulcer aetiology on the QoL of patients. | No statistically significant differences were observed between demographic and laboratory data for patients with different Wagner grade lesions. Patients with DFU had significantly lower scores in all domains of SF-36 than the general population. Patients with higher Wagner grade had lower SF-36 scores in all domains. | SF-36 |

| Ali Alzahrani et al. Saudi Arabia, 2013 [36] | Observational, case-control 180 patients, 2 groups | Observe association between religious connection and QoL in patients with and without DFU. | DFU patients had reduced QoL in all SF-36 scores compared to people living with diabetes without lesions and healthy controls, and this reduction increased with ulcer severity, duration, and number. A positive relationship was observed between religious connectedness and MCS score for patients with DFU. | SF-36 |

| Siersma et al. Europe, 2013 [37] | Prospective-observational Multicenter 1232 patients | To identify factors responsible for a reduction in QoL associated with DFU and their relative importance. | Patients with DFU had a reduction in overall QoL, with the primary determinant of reduction being the inability to stand or walk without help. Other factors that reduced the EQ-5D score included ulcer size, CRP concentration, and ischemia. Factors affecting pain/discomfort domain scores included infection, PAD (peripheral arterial disease), and DPN (diabetic peripheral neuropathy). | EQ-5D-3L |

| Fejfarova et al. Czech Republic-UK-USA, 2014 [38] | Case-control 152 patients, 2 groups | To evaluate the impact of diabetic foot on daily life, on psychological and socioeconomic aspects of patients and compare results with patients with DM without complications from DF. | DF (diabetic foot) patients have a worse QoL than controls without diabetic foot, especially in terms of physical health and environment, and are more frequently depressed. DF patients have basic education and, a small percentage work and are poorly self-sufficient. The presence of previous amputations has a negative impact on the environmental domain and employment status. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| McDonald et al. Australia, 2014 [39] | Case-control 270 patients, 2 groups: 50 amputees and 240 diabetics no amputation as controls | To statistically assess possible group differences on medical and demographic variables to examine the psychosocial impact of diabetes-related amputation. | The presence of amputation leads to medical problems such as increased insulin use, micro/macrovascular complications. Patients with diabetes and amputation have more depressive symptoms, poorer physical QoL, and greater disturbance of body image. After multivariate analysis, these differences remain for body image. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| Raspovic, Wukich USA, 2014 [40] | Case-control 106 patients, 2 groups | To compare QoL in patients with CN (Charcot neuro-osteoarthropathy) and in patients with DM without podalic involvement. | Patients with CN had lower FAAM (foot and ankle ability measure) scores than controls without foot involvement. For SF-36 scores, no differences in MCS were observed, while PCS was reduced compared to controls. Patients with CN had lower scores in 7 of 8 SF-36 domains. | SF-36 FAAM |

| Raspovic, Wukich USA, 2014 [41] | Case-control 47 patients with infection and 47 controls | To compare QoL between patients admitted for DFI (diabetic foot infection) and patients with DM (diabetes mellitus) without foot involvement. | Patients admitted with DFI reported low scores in all domains of SF-36, including PCS and MCS. FAAM scores were also significantly reduced compared to the control group without foot involvement (2 SD (standard deviation) on ADL (activity of daily living) score and 1.5 SD on SPORT score). | SF-36 FAAM |

| Siersma et al. Europe, 2014 [42] | Prospective-observational Multicenter 1015 patients | To evaluate whether QoL in patients with newly discovered ulcer has prognostic significance for healing, major amputation or death. | In patients with newly discovered ulcers, HRQL is not a predictor for healing, while a reduction in QoL scores in physical domains is associated with a significant increase in major amputations and death. | EQ-5D-3L |

| Raspovic et al. USA, 2015 [43] | Case-Control 57 patients, 2 groups | To compare QoL in patients with CN with a group of patients with CN and midfoot ulcer. | No significant differences were observed in SF-36 scores between patients with Charcot without ulcer (group 1) and those with ulcer (group 2) nor between FAAM scores. The only difference observed between the two groups was that patients with CN without ulcer had lower scores in the bodily pain domain than those with CN and ulcer. | SF-36 FAAM |

| Sekhar et al. India, 2015 [44] | Cross-sectional 400 patients, 2 groups | Evaluate QoL among people living with diabetes with and without ulcers. | DFU patients showed statistically significant differences compared to patients without DFU in all SF-36 subscales, especially physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, and role limitations due to emotional health. A significant difference was also observed in MCS and PCS scores. For DFU patients, DFS-SF scores were low in all domains. | SF-36 DFS-SF (diabetic foot ulcer scale—short form) |

| Hoban et al. Canada, 2015 [45] | Case-Control 96 patients, 2 groups and 21 caregivers | To evaluate the effect of diabetic foot-related problems on mental well-being in patients and caregivers. | Diabetic foot patients reported lower scores in 6 of 8 SF-36 domains and in the PCS compared to those without foot involvement, were more depressed, andhad more pain and suicidal behaviours. Caregivers reported higher levels of anxiety and depression, and a positive correlation was observed between alcohol dependence and the MCS of SF-36 in caregivers of diabetic foot patients. | SF-36 |

| Crews et al. U.K-USA, 2016 [46] | Prospective Multicenter 79 patients DFU | To evaluate the association between adherence to offloading and the number of ulcers healed during the treatment period. To identify potential physical and psychological determinants of adherence to offloading. | Smaller ulcers at baseline and better adherence to offloading significantly predicted reduction in ulcer size at 6 weeks. Larger and more severe ulcers at baseline, severe neuropathy, and higher NeuroQoL pain scores were significantly predictive of offloading adherence. Postural instability worsened offloading adherence. | NeuroQoL |

| Pedras et al. Portugal, 2016 [47] | Longitudinal 108 patients DFU | To identify predictors of HRQoL after surgery, to analyse the differences in HRQoL before and after surgery, to explore the moderating role of 1st vs. previous amputation in the relationship between physical and mental HRQoL before and after surgery in DFU patients. | SF-36 PCS score was significantly reduced after surgery, MCS score did not show significant differences. Previous amputation had a moderating effect on PCS and MCS scores before and after surgery. | SF-36 |

| Nemcová et al. Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary 2017 [48] | Cross-sectional 525 patients DFU | Assessing QoL in patients with DFU in the Visegrad region. | Demographic determinants of QoL reduction were identified, including higher age, living alone, need for care, not belonging to groups or organizations. Clinical determinants of QoL reduction were high frequency of ulceration, higher severity of ulcer according to Wagner classification, presence of pain, high BMI, long duration of diabetes, and ulcer treatment. Significant differences in QoL were observed between the geographical regions considered in the study in all WHOQOL-BREF domains, with patients from Hungary having the worst scores in all domains. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| Siersma et al. Europe, 2017 [49] | Prospective observational cohort study 1232 patients | To evaluate whether the presence of diabetic complications also influences the improvement of HRQoL during DFU treatment. | Significant improvement in QoL is observed in almost all EQ-5D domains when the ulcer heals, regardless of whether it heals within 6 or 12 months. Baseline QoL is worse in the presence of comorbidities in patients who heal within 1 year and in those who do not heal, compared to those who heal within 6 months. In patients who do not heal after 12 months, the usual activities and pain/discomfort domain scores and EQ-5D index improve even in the presence of heart failure. An improvement in the usual activities score is also observed even in the presence of visual impairment or neurological disorders. | EQ-5D-3L |

| Spanos et al. Greece, 2017 [50] | Prospective non-randomized cohort study 103 DFU patients | To evaluate factors associated with the healing process or limb salvage, in patients with DFU and assess the impact of treatment on QoL. | Ulcer healing is associated with the Texas University Wound Classification grade and the degree of infection. Lower Texas grade ulcers are more likely to heal, and for every 1-unit increase of the infection score, the risk of non-healing increases by 15%. The likelihood of minor amputation increases for lesions grade > II of the Texas classification, in the presence of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and as the neuropathy score increases. The risk of major amputation is associated with a non-palpable popliteal artery, and hospitalizations, and increases by 3.5% for each day of delay until referral. QoL improved significantly in all DFS-SF domains after 12 months of follow up regardless of treatment type. | DFS-SF |

| Pickwell et al. Europe, 2017 [51] | Prospective-observational Multicenter 1088 patients, 2 groups | To determine the impact of minor amputations on QoL by comparing changes in QoL in patients healed after minor amputation with those in patients healed by primary intention. | Conservatively treated ulcers heal faster than those resulting from minor amputations, which are larger, deeper, often infected and localized to the toes. In patients who heal, QoL improves significantly. EQ-5D scores showed an improvement, although not significant, in patients who underwent minor amputations compared to conservative treatment. | EQ-5D-3L |

| Raspovic et al. USA,2017 [52] | Case-control 90 DFU patients, 2 groups 30 ESRD (end stage renal disease) and 60 no ESRD | To assess the impact of end-stage renal disease on QOL in patients with diabetic foot. | Patients with diabetic foot and ESRD had lower scores for the SF-36 physical, social and PCS domains than patients with diabetic foot without ESRD. No differences were observed between the two groups for the MCS score and the other SF-36 domains and for the FAAM score. Patients who underwent major amputation or surgery reported lower SF-36 scores in the PCS and physical, social, role-emotional domains. No significant impact on MCS was observed for mortality, amputation, or surgery. ESRD was significantly related to PCS score but not to MCS score. | SF 36 FAAM |

| Wukich et al. USA, 2017 [53] | Observational cohort study 81 patients | To evaluate HRQoL after major lower limb amputation in a cohort of patients with diabetes mellitus. | Patients who completed the questionnaires before and after transtibial amputation surgery showed significant improvement in all SF-36 domains, PCS and MCS, and FAAM scores. Post-intervention scores improved if the prosthesis allowed effective ambulation. Patients who were unable to ambulate pre-intervention had significantly lower scores on the SF-36 physical domains. Patients who were non-ambulant post-intervention had lower scores on the SF-36 general health domain and lower FAAM scores than those who were ambulant post-intervention. | SF 36 FAAM |

| Pedras et al. Portugal, 2018 [54] | Cross-sectional 202 patients DFU | To analyse the relationships between anxiety, depressive symptoms and functionality as predictors of QoL in patients with DFU, considering clinical variables. | A negative correlation was observed between PCS and MCS scores and gender, age, number of hospitalizations in the past year, pain, depression and anxiety symptoms. PCS score wss also negatively associated with ulcer duration. Negative predictor factors for MCS were anxiety and depression symptoms. Negative predictors for PCS were pain and depression symptoms. | SF36 |

| Ahn et al. USA, 2018 [55] | Retrospective 300 DM patients, 2 groups | To assess physical and mental health-related QoL in patients with DM with or without diabetic foot and to evaluate whether mental health-related QoL is significantly different using orthogonal or oblique factor analysis. | Patients with diabetic foot complications showed significantly lower PCS scores when calculated with both orthogonal and oblique rotation factor coefficients. MCS was significantly reduced when calculated with oblique rotation factor coefficient. | SF36 |

| Del Core et al. USA, 2018 [56] | Cross-sectional comparison 240 patients 120 M–120 F | To evaluate the impact of gender on QOL with a generic tool (SF 36) and a specific one (FAAM) in a cohort of male and female patients with diabetic foot. | Women showed significantly lower PCS scores than men, calculated with both orthogonal and oblique rotation coefficients. The worst scores were found in the domain of physical function and bodily pain. No significant differences are observed between men and women for MCS scores with both orthogonal and oblique rotation coefficients. No significant differences are observed between men and women for FAAM scores | SF36 FAAM |

| Alosaimi et al. Saudi Arabia, 2019 [57] | Case-control 209 DM patients: 45 DFU and 164 controls | To compare QOL and its psychosocial determinants between patients with and without diabetic foot ulcers. | There was a negative correlation with QoL and presence of symptoms of anxiety, depression and the severity of somatic symptoms. After multivariate analysis, depression remained a negative determinant of QoL, regardless of DFU status. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| Khunkaew et al. Thailand, 2019 [58] | Cross-sectional 41 DFU patients | Evaluating QoL and foot management in people with DFU. | The DFS-SF scores reported by the population considered are high and indicate good QoL. The lowest score was observed in the “worried about ulcers” domain. Only a third of patients reported having received education on foot care. Almost all patients (97.6%) wash their feet every day, most do not test the water temperature and approximately 63% dry between the toes; 70% of patients report walking barefoot at home. The most frequent barrier to foot care is not having a mirror to check the sole of the foot, and lack of knowledge on how to use it correctly. | DFS-SF |

| Alrub et al. Jordan, 2019 [59] | Cross-sectional 144 patients DFU | To determine factors associated with QoL among people living with diabetes with DFU in Jordan. | DFU patients reported low DFS-SF and SF-8 scores. Higher DFS-SF scores were associated with male gender, high level of education, no stressful events in the past year, not having PVD (peripheral vascular disease), no soft issue infection, lower Wagner classification grade, and normal BMI. | DFS-SF SF 8 |

| Iversen et al. Norway, 2020 [60] | RCT 182 DFU patients 94 Telemedicine and 88 Outpatient | To compare changes in health, well-being, and QoL between patients with DFU undergoing telemedicine follow-up and patients undergoing standard outpatient care. | No significant differences were observed in the scores between the group of patients followed with SoC (standard of care) and that with telemedicine, which were almost unchanged between the baseline and follow-up measurements with both generic and specific PROMs. Telemedicine did not have significant effects on health, well-being and QOL outcomes compared to the SoC. | EQ-5D-5L NeuroQoL |

| Jayalakshmi et al. India, 2020 [61] | Cross-sectional, descriptive 118 DFU patients | To evaluate the impact of DFU on the different components of patients’ QoL and determine the associated factors. | Patients with DFU reported the lowest percentage of CWIS scores in the domain of “well-being” and the lowest in the domain of “social life stress”. A positive correlation was observed between QoL and the satisfaction domain of CWIS; a negative correlation was observed between QoL and satisfaction with stressful experience of social life and physical symptoms experience. The factors that most influence QoL are symptomatic living, social experiences, and stress, followed by satisfaction and then by stress in social life. | CWIS |

| Polikandrioti et al. Greece, 2020 [62] | Cross-sectional 195 patients DFU | To explore QoL levels in DFU patients and associated factors involved and the impact of anxiety, depression and treatment adherence on QoL. | Patients with DFU report moderate levels of QoL in the SF-36 general health domain and moderate to high levels in the SF-36 emotional well-being, pain, social functioning, and energy/fatigue domains. The lowest scores are reported in the physical functioning, role physical, and role emotional domains. Factors negatively associated with patients’ QoL and statistically significant are: age, education, number of children, other concomitant pathologies, daily blood glucose measurement, Wagner classification and alcohol consumption, as well as work and smoking habits but also compliance, with periodic checks and treatment and place of residence. QoL is better if anxiety and depression levels are low and based on adherence to exercise guidelines. | SF-36 |

| Kuang et al. China, 2021 [63] | Cross-sectional, prospective 98 DFU patients | To determine the role of psychological resilience in the QoL of patients with DFU and in the regulation of self-efficacy, together with the risk factors of psychological resilience. | It is observed that patients with high psychological resilience had significantly higher levels of SF-36 for self-efficacy, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotion, and mental health domains compared to participants with low psychological resilience. Negative determinants of self-efficacy are low psychological resilience, older age, low education, unemployment, and higher level of HbA1c. Negative determinants of QoL are low psychological resilience, older age, lower perceived social support, and higher level of HbA1c. Men have lower psychological resilience than women. | SF-36 |

| Reinboldt-Jockenhöfer et al. Germany, 2021 [64] | Cross-sectional, Retrospective, Multicenter 381 patients (171 with DFU) | To investigate differences in physical, psychological and daily life-related QoL in patients with different causes of chronic wounds. | DFUs accounted for 44.8% (171/381) of the selected patient sample. Patients with DFU were significantly younger than those with arterial leg or mixed ulcers and were more frequently male. Patients with DFU reported discomfort in the “everyday life-related QoL” domain. The diagnosis of diabetic foot ulcer determined lower scores in the psychological subscale, a reduction in the “everyday life-related QoL” score and was a predictor variable for the reduction of general wound-related QoL. Females reported reduction in psychological and general wound-related QoL. | Wound-QoL |

| Kolarić et al. Croatia, 2022 [8] | Observational 382 patients with DM2 (diabetes mellitus 2) | To compare the QoL of patients with type 2 diabetes based on their chronic complications. | Patients with DM2 in the selected sample present neuropathy as the major complication, followed by retinopathy; nephropathy and DFU are represented in equal percentage. Patients with complications are older. Hospitalizations are more frequent in patients with DFU. Patients with DFU reported the highest WHOQOL-BREF scores in the psychological domain, as did patients with neuropathy, but the lowest in the physical domain. Low scores in the physical functioning domain are also reported by patients with nephropathy. Patients with neuropathy and retinopathy reported low scores in the social functioning domain. High scores were reported in the environmental domain by patients with nephropathy and retinopathy. Patients with multiple chronic complications report low scores for the physical functioning domain but high for the environmental domain. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| Juzwiszyn et al. Poland, 2022 [65] | Observational 99 patients | To evaluate the relationship between QOL, level of disease acceptance and nutritional status in diabetics undergoing lower limb amputation (58 major and 42 digital amputations). | Patients reported higher WHOQOL-BREF scores in the social domain, intermediate in the environmental and mental domains, and lower in the physical domain. Women reported lower scores than men, but no significant correlations were observed between gender and QoL; 5.1% of the patients considered are malnourished and statistically significant differences are observed between gender and age with nutritional status. Women have a worse nutritional status than men and older people are more malnourished. Less malnutrition corresponds to better QoL. Older patients accept the disease less. Patients with higher scores in all QoL domains and who report a better QoL accept the disease better. | WHOQOL-BREF |

| Perrin et al. Australia-Holland, 2022 [66] | Cross-sectional analysis of multicenter RCT (randomized control trial)s 304 patients | To evaluate QoL and associated factors in patients with DM at high ulcerative risk. | In patients at high risk of developing DFU, the highest score is observed in the mental health domain and the lowest for the general health domain on the SF-36 questionnaire. Factors associated with QoL are the use of walking aids with lower mean scores in the physical functioning, role physical and bodily pain domains, ethnicity with Caucasian patients having higher scores in the physical, emotional, mental health, social functioning, and bodily pain domains. | SF-36 |

| Delpierre et al. U.K., 2023 [67] | Monocentric longitudinal observational 18 patients | To evaluate the short-term impact of non-removable offloading devices on physical activity and diabetic foot ulcer-related QOL in a small sample of community-dwelling people with DFUs. | After three weeks of follow-up, a significant difference in DFS score for non-compliance domain was observed. No differences in DFS scores were observed at six-week follow-up or at multiple time points. Patients reported low scores in the physical activity domain already at baseline, with worsening scores at 3 and 6 weeks in 2/3 of patients. The results suggest that non-removable offloading devices may have a negative effect on patients’ adherence to overall diabetes treatment and may impact financial well-being due to indirect costs, such as travel to periodic check-ups and reduced income due to reduced working capacity. | DFS |

| Hamid et al. Sudan, 2024 [68] | Cross-sectional comparison 120 patients, 2 groups | To compare QoL between people living with diabetes with and without DFU and determine factors related to low QoL. | DFU patients reported lower scores in 5 of 8 domains of SF-36 compared to diabetics without ulcer, but reported higher scores in the domains of general health perception and emotional well-being. There was a significant difference in the general score of SF-36 between the two groups, greater in the group of people living with diabetes without DFU. Women had lower scores than men in the domains of physical functioning and general health. Divorced or widowed patients reported lower scores, a higher level of education was a positive predictor of QoL especially in the domains of emotional role, energy/fatigue and pain. Ulcer duration correlated positively with all domains of SF-36 except the social one. | RAND-36 |

| Byrnes et al. Australia, 2024 [69] | Cross-sectional multicenter 376 patients, 5 groups | Evaluate and compare QoL in patients with DFU: recovered, non-infected, infected, hospitalized and amputated. | 75.3% of patients reported mobility problems, 35.6% self-care problems, 71.3% problems with daily activities, 69.7% pain/discomfort, 56.1% anxiety and depression. Patients admitted for DFU were younger than the other groups. Compared to patients with healed ulcer, those with non-infected DFU had more mobility problems while those with amputation were unable to perform daily activities. Patients with infected DFU had significantly lower EQ-5D index and VAS (visual analogue scale) scores than the other groups. The infected DFU condition remained the worst and maintained significant score differences compared to the healed ulcer status even after adjustment for sex and age. | EQ-5D-5L |

| Alvaro-Afonso et al. Spain, 2024 [70] | Cross-sectional observational 141 patients | Assessing QoL of Spanish Patients with DFU Using DFS-SF. | The lowest score was observed in the “worried about ulcers” domain of the DFS-SF questionnaire, while the highest was observed in the physical health domain. Regarding this domain, significantly lower scores were reported for patients with ischemic DFU. Significant differences between the physical health and “worried about ulcers” domains were observed, depending on level of education. Patients with dyslipidaemia reported lower scores in both the “worried about ulcers” and “bothered by ulcer care” domains. In the case of previous minor amputation, significant differences were observed in the domains of leisure, dependence/daily life, negative emotions, “worry about ulcers/feet”, and “worry about ulcer care”. A significant negative correlation was observed between the SINBAD (site, ischemia, neuropathy, bacterial infection, area, depth) classification score and the DFS-SF leisure, physical health, dependence/daily life, and “bothered by ulcer care” domains. A significant negative correlation was observed between the ulcer duration and all the DFS-SF domains. | DFS-SF |

| Instrument | Type | Domain/Subscale | Scoring System | Comment | Studies Using PROM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CWIS Cardiff wound Impact Schedule [7,10,71] | Specific | 26 questions in 3 domains: physical symptoms and daily life, social life, general well-being → 5-point Likert scale + 2 questions measuring global QoL and satisfaction with QoL. For these 2 items, questions are graded on a 11-point Likert scale | Score of each question is summed and transformed into a 0–100 scale Higher score = better QoL | For all chronic wounds Shows sensitivity to wound healing in RCTs evaluating type of dressing in DFUs. Lacks sensitivity to wound severity. | 24; 61 |

| DFS Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale [10,72] | Specific | 58 questions in 15 subscales (Leisure, Physical health, Daily life, Dependence, Family and friends, Treatment compliance, Positive relationships, financial burden, Side effects, Diet, Compliance, Medical complications, Satisfaction) Questions are graded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “not at all or none of the time”, 5 = “a lot, all of the time, or extremely”). | Score 0–100 (0 = poorer QoL) | Developed to assess the impact of DFU and treatment on QoL in people with diabetes. Specific measure for DFU and not generic for diabetes. Ability to discriminate between patients with diabetes and healed ulcer or active ulcer. Sensitive to changes in wound status. Appropriate for use in clinical trials of patients with DFU. | 22; 25; 67 |

| DFS-SF Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale-Short Form [10,73] | Specific | 29 questions in 6 subscales (Leisure, Physical health, Dependence/daily life, Negative emotions, Worries about ulcers/feet, Impact of ulcer care) Questions are graded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “not at all or none of the time”, 5 = “a lot, all of the time, or extremely”). | Score 0–100 (0 = poorer QoL) | Shortened and faster version of DFS. About 15 min to compile. Validated against DFS. | 44; 50; 58; 59; 70 |

| EQ-5D EuroQoL 5D Health utility Index [10,19,74] | Generic/ Utility | 5 domains (Mobility, Self-care, Usual activities, Pain or discomfort, Anxiety or depression). Three (EQ-5D-3L) or five (EQ-5D-5L) possible answers for each domain. Accompanied by VAS analogue scale 0–100 (0 = worst imaginable health; 100 = best imaginable health) One additional question on current health state: is better, the same, or worse than your general health level over the past 12 months? | Scores for each response are summed using a formula that weights the different domains based on the EQ-5D scores of the general population. The generated numerical index ranges from −0.594 to 1. (Score 0 represent no QoL; <0 states perceived worse than death) | The 5 dimensions assessed can be transcribed into 243 possible health states. Intended as a research tool—not recommended for use in routine clinical practice. Used for the economic evaluation of foot care/treatment in diabetics. | 19; 37; 42; 49; 51; 60; 69 |

| FAAM Foot and Ankle Ability Measure [75] | Specific | 2 sections

| Item score totals, which range from 0 to 84 and 0 to 32 for the ADL and Sports subscales, respectively, were transformed to percentage scores. Higher scores represent a higher level of function for each subscale. | Region-specific, designed to assess lower limb function. Validated to measure physical function in patients with a broad spectrum of lower limb musculoskeletal disorders. Also responsive to lower limb function assessment in patients with diabetic foot. Most adapted in different languages and populations | 40; 41; 43; 52; 53; 56 |

| NeuroQoL [7,76] | Specific | 35 questions

| 2 scores: physical symptoms and psychosocial function For each of the 27 specific questions, the patient is asked to judge the degree to which each experience was a nuisance or an important thing. The discomfort/importance has a score from 1 = not at all to 3 = very much The score is calculated by multiplying the Likert scale score with the corresponding discomfort/importance score. Higher score = worst QoL | Patients with peripheral neuropathy and diabetic foot ulcers. Poorly sensitive to lesion severity. 2 scores: physical symptoms and psychosocial function | 46; 60 |

| RAND-36 [17,77] | Generic | Assesses the same dimensions of the SF-36 and includes the same item on perceived change in health | Like SF-36 but with differences in scoring algorithm. It is possible to calculate two summary scores (physical health and mental health) | Adaptation of the SF-36 developed by the RAND Corporation | 44; 68 |

| SF-36 The medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey [10,78] | Generic | 36 questions for 8 domains (Physical function, Bodily pain, General health perception, Vitality, Social functioning, Role limitations due to physical/emotional problems, Mental health). | 3 scores:

| Facilitates comparison with other chronic pathologies. Not specific for diabetic foot syndrome. Most frequently used. | 20; 21; 22; 23; 25; 26; 27; 28; 29; 30; 31; 32; 33; 34; 35; 36; 40; 41; 43; 45; 47; 52; 53; 54; 55; 56; 62; 63; 66 |

| SF-12 The medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey [10,79] | Generic | 12 questions measuring the 8 domains of the SF-36. | Overall HRQL Score 0–100 (0 = poor HRQL). Two summary scores, PCS and MCS, can also be computed from the sub-scale scores. | Short and adapted version of the SF-36. Brevity lends its use for condition-specific investigations used in clinical trials. Can be converted to SF-6D and used for economic evaluations. | 24 |

| SF-8 The medical Outcomes Study 8-item Short-Form Health Survey [80] | Generic | 8 questions measuring the 8 domains of the SF-36. | Overall HRQL Score 0–100 (0 = poor HRQL). Two summary scores, PCS and MCS, can also be computed from the sub-scale scores. | Short and adapted version of the SF-36. Derived from the SF-36 to minimize respondent burden. A valid tool for assessing HRQoL, especially in large-scale observational studies. | 59 |

| WHOQOL-BREF [9] | Generic | 26 items in 4 domains: physical, psychological, social and environment Questions are graded on a 1–5 point Likert scale (1 = “disagree” or “not at all” and 5 = “totally agree” or “very”). | Domains are not scored where 20% of items or more are missing, and are unacceptable where two or more items are missed (or 1-item in the 3-item social domain). The scores are transformed on a scale 0–100 | Assesses the individual health and well-being over the past two weeks. Short version of the WHOQOL-100. | 8; 38; 39; 48; 57; 65 |

| WoundQoL [7,81] | Specific | 17 questions in 3 domains:

Each question, 5 answers (score 0–4): not at all, a little, moderately, a lot and very much | Overall score calculated by adding all questions. It can only be computed if at least 75% of the items have been answered. Subscale scores calculated by adding individual questions. Higher score = Worst QoL | Patients with chronic wounds. | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amato, E.; Giangreco, F.; Iacopi, E.; Piaggesi, A. Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome (PROMs) Measures in Diabetic Foot Disease Management—A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176116

Amato E, Giangreco F, Iacopi E, Piaggesi A. Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome (PROMs) Measures in Diabetic Foot Disease Management—A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176116

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmato, Elisa, Francesco Giangreco, Elisabetta Iacopi, and Alberto Piaggesi. 2025. "Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome (PROMs) Measures in Diabetic Foot Disease Management—A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176116

APA StyleAmato, E., Giangreco, F., Iacopi, E., & Piaggesi, A. (2025). Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome (PROMs) Measures in Diabetic Foot Disease Management—A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176116