Review of D-Shape Left Ventricle Seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT), Similar to the Movahed Sign Seen on Cardiac Gated Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as an Indicator for Right Ventricular Overload

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

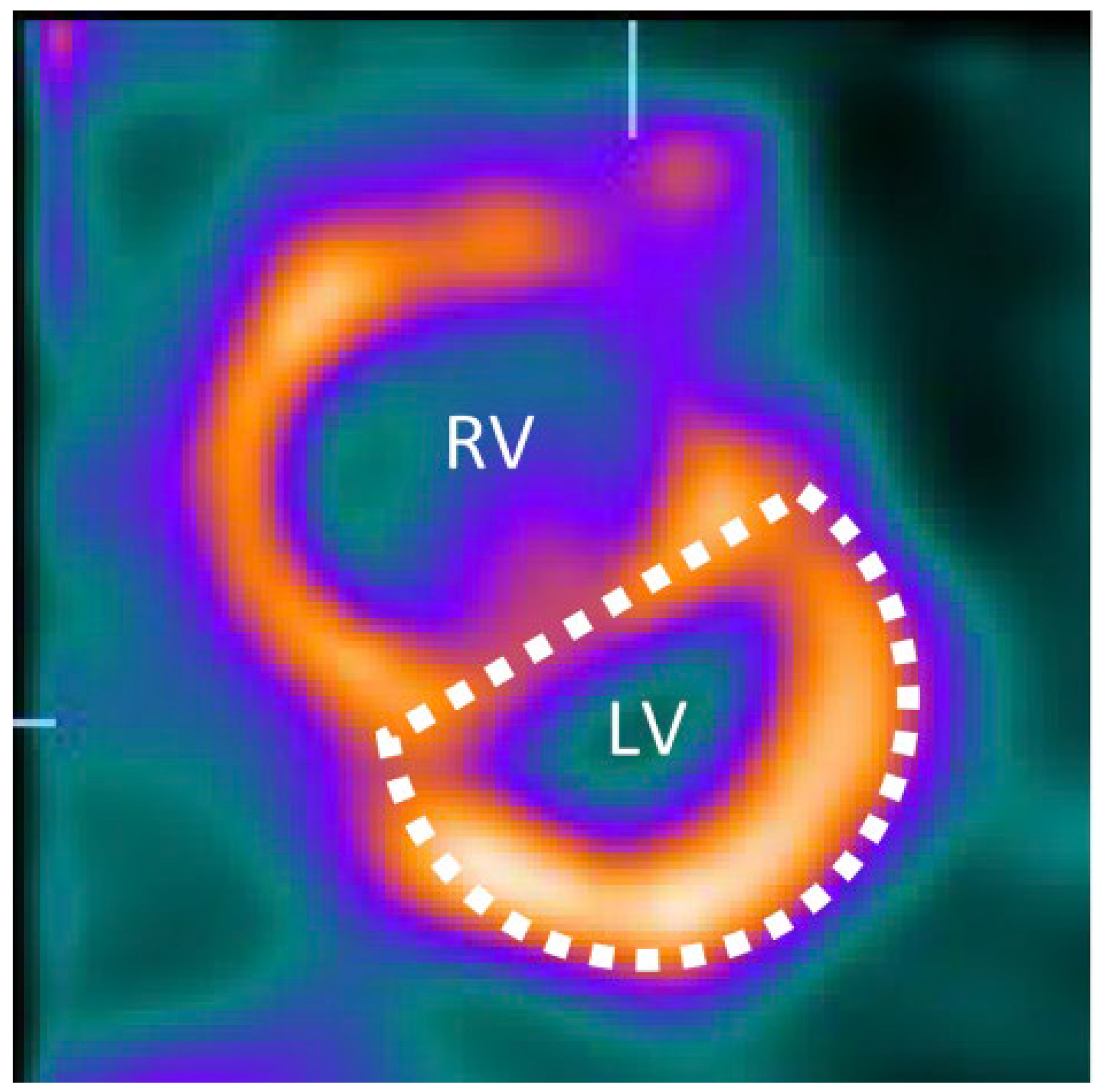

3. Pathophysiological Basis and Origins

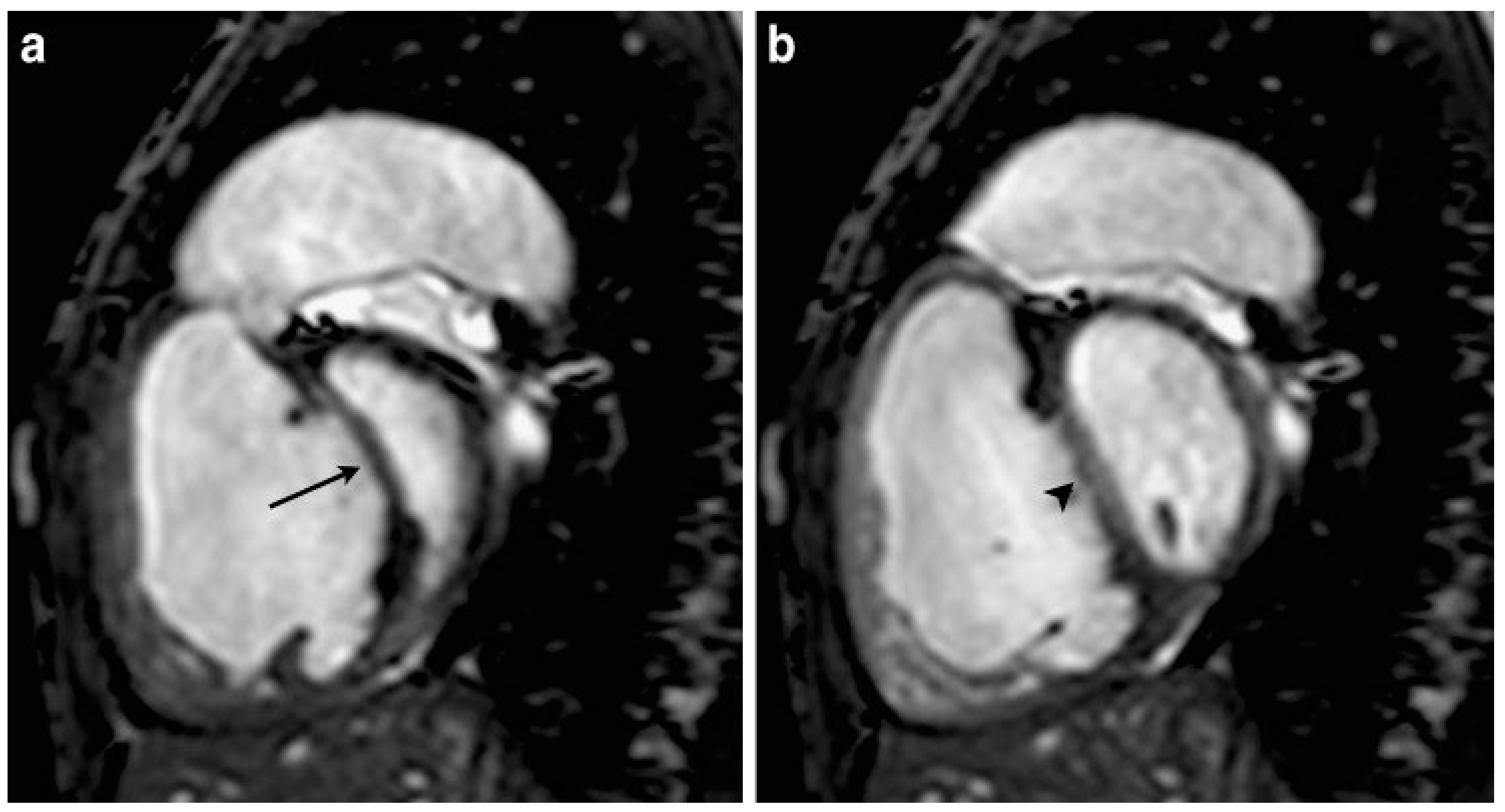

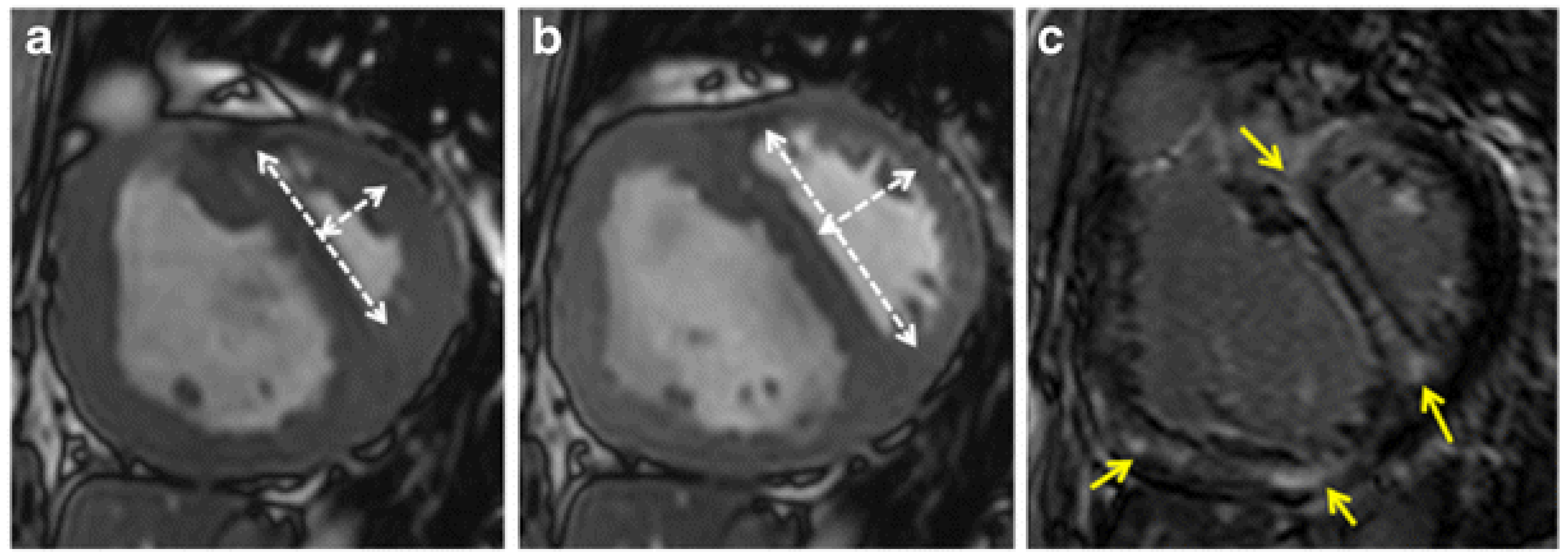

4. Imaging Characteristics on MRI

5. Imaging Characteristics on CT

6. Diagnostic Utility, Differential Diagnosis, and Clinical Contexts

- Pulmonary hypertension: This is by far the most common cause in practice of a chronic D-shaped LV. This can be idiopathic PAH or PH secondary to left heart disease, lung disease, or chronic thromboembolism. In PH, septal flattening is usually present in both systole and diastole on imaging. Additional MRI clues might include RV hypertrophy and dilated pulmonary arteries. In advanced PH, MRI and CT often demonstrate a flattened septum [30,34]. Clinically, these patients present with dyspnea on exertion and signs of right heart failure. The sign correlates with elevated RV systolic pressure (>60 mmHg) and typical RV remodeling in PH [35].

- ○

- Left heart disease leading to PH: Severe left heart failure or mitral valve disease can cause secondary PH. In such cases, one might see a D-shaped LV on imaging despite the primary issue being left-sided, because long-standing post-capillary PH causes RV pressure elevation [36,37,38]. For example, severe mitral stenosis can lead to a D-shaped LV due to resulting PH and RV overload (though the condition also affects LV filling). In advanced heart failure with preserved EF and resultant PH, septal flattening can also occur.

- ○

- Cor Pulmonale from Lung Disease: Chronic lung diseases (COPD, interstitial lung disease) often cause gradual RV pressure overload (cor pulmonale). In advanced COPD with resting PH, CT scans can show a D-shaped LV along with large central pulmonary arteries [39,40,41,42]. MRI could similarly show it. These patients will have other signs like enlarged pulmonary artery diameter on CT > 30 mm, indicating PH [43].

- ○

- Acute pulmonary embolism: This is a leading cause of acute septal flattening. In massive PE with obstructive shock, the Movahed sign may be seen on a CT angiogram as septal bowing [25]. Echo would show McConnell’s sign (RV free-wall hypokinesis with apical sparing) alongside the D shape [46,47]. Clinically, these patients may be hypotensive, tachycardic, with acute right heart strain on ECG. The Movahed sign on CT in this context is an emergency finding, indicating likely need for aggressive therapy (thrombolysis or embolectomy).

- Right ventricular infarction: An acute RV myocardial infarction can cause acute RV failure and increased RV end-diastolic pressure, potentially leading to septal shift. The septum might move dyskinetically rather than purely flatten, and RV infarction rarely causes significant septal flattening unless there is concomitant PH [48,49].

- Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy or Failure: End-stage RV failure from any cause can produce a D-shaped LV if pressures equalize abnormally [3,5,40]. In advanced arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), significant RV dilation and systolic dysfunction can produce septal flattening and a D-shaped LV, particularly when RV pressures are elevated. However, this remains a relatively uncommon etiology compared to PH or acute PE and is usually accompanied by other overt features of RV failure.

- Volume overload of the RV, such as large ASD (especially ostium secundum ASDs with significant left-to-right shunt) or severe chronic TR. These typically produce diastolic septal flattening. An ASD, for instance, will enlarge the RV, and in diastole, the septum flattens due to the increased RV filling volume [3,5,13]. In systole, if pulmonary pressures are normal, the LV may pop back to round. MRI with phase contrast can quantify a shunt if present (Qp:Qs ratio) [5,50].

- Congenital Heart Disease:

- ○

- Atrial Septal Defect: Large, long-standing ASDs can lead to RV volume overload and, if Eisenmenger physiology develops, pressure overload [40,51]. An unrepaired ASD may show diastolic flattening; if pulmonary pressures rise (Eisenmenger syndrome), systolic flattening appears as well [3,5]. In pediatric patients with big ASDs, MRI is sometimes used to quantify shunts and will show the D-shaped LV at end diastole [5,50,52].

- ○

- Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) with pulmonary hypertension: A large VSD initially causes volume overload of both ventricles. If pulmonary vascular disease ensues, RV pressure rises, and a D shape can appear [3,53,54,55]. In infants with large VSDs, one might see this on echo if they develop early PH [5,12,53].

- ○

- Tetralogy of Fallot: Before repair, these patients have RV pressure equal to systemic (due to the VSD and RV outflow obstruction), but since the pressures are balanced by the VSD shunt, the septum may not flatten much in diastole. After repair, if pulmonary regurgitation leads to volume overload, diastolic flattening can occur. However, this is a less typical scenario for a persistent D-shaped LV [55,56,57].

- ○

- Constrictive pericarditis: Interestingly, constrictive pericarditis can also cause a form of septal flattening, though it is usually a transient “septal bounce” rather than a persistent D shape. In early diastole, the septum may shift leftward with inspiration (ventricular interdependence) and produce a brief D-shaped LV. The context of constriction (pericardial thickening, respiratory variation on Doppler) differentiates it [19,60,61]. Thus, constriction is in the differential for any unusual septal motion. In MRI or CT, one clue favoring constriction is that septal flattening occurs only in early diastole and varies with respiration, as opposed to fixed flattening in all phases for true RV overload.

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) or Acute Asthma: Severe acute lung processes can cause acute PH and RV strain (acute cor pulmonale). In ARDS, 20–25% develop acute cor pulmonale; CT may show a D-shaped LV, though it is not always obtained [62,63,64,65]. Echocardiography more often demonstrates septal flattening in severe ARDS [66,67].

- Miscellaneous: Large right-sided tumors or masses (like a huge RV fibroma or aneurysm) theoretically could compress the LV and mimic septal flattening, but this is exceedingly rare. Likewise, septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may distort LV shape without producing true septal flattening.

7. Prevalence and Epidemiological Insights

- In Pulmonary Hypertension: Septal flattening is a common feature in moderate to severe PH. Echocardiographic studies have documented D-shaped LV in a substantial fraction of PH patients; Bossone et al. reported that systolic flattening of the interventricular septum was observed in 90% of patients with primary PH, with the majority having pulmonary artery systolic pressures greater than 60 mm Hg [70]. On MRI, almost all patients with severe PH will exhibit some degree of septal flattening. Several studies support this finding. For instance, Pandya et al. demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between septal curvature and mPAP in pediatric patients with PH, with correlation coefficients of −0.81 and −0.85 at baseline and during vasodilator testing, respectively [20]. Similarly, Sciancalepore et al. found that septal curvature values progressively decreased with increasing severity of PH and correlated well with invasive pressures, with r-values ranging from 0.78 to 0.79 [71]. Roeleveld et al. also reported a significant relationship between septal curvature and systolic pulmonary arterial pressure, with a correlation coefficient of 0.77 [21]. Essentially, by the time pulmonary pressure approaches systemic levels, the D-shaped LV emerges [3,72,73]. Thus, epidemiologically, among patients with World Health Organization Group 1 PAH, the Movahed sign could be present in over half of those in NYHA class III–IV or with severe hemodynamics. However, exact prevalence varies by cutoff used and patient mix.

- In Acute Pulmonary Embolism: The prevalence of septal bowing on CT in acute PE corresponds to the proportion of patients with massive or submassive PE (those causing RV strain). Kim et al. reported that septal bowing was observed in 32.7% of patients with massive or submassive PE and in 5.5% of patients with small PE [27]. Similarly, Araoz et al. found that septal bowing was associated with an increased risk of short-term death, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.98 in univariate analysis and 1.97 in multivariate analysis, although the sensitivity was low and interobserver variability was fair [28]. Beenen et al. also highlighted the prognostic value of septal bowing in their study, emphasizing its association with adverse outcomes [74].

- General Population/Incidental: In the general population, a D-shaped LV is essentially never seen unless a person has one of the pathologies above. Incidental detection on a non-cardiac CT scan (e.g., a trauma CT where the heart is visible) would be rare and should prompt evaluation for unrecognized PH or an acute event. Epidemiologically, one might say the sign has a prevalence approaching 0 in healthy individuals and 0 in patients with normal RV pressure. In patients with any form of significant RV overload, the prevalence rises with the severity of overload. For instance, among patients with COPD and cor pulmonale, echo studies often show septal flattening in about 20–30% of moderate COPD and up to 50% in very advanced COPD with resting PH [39].

8. Clinical and Prognostic Implications

- Indicator of Disease Severity: In chronic conditions like PH, a D-shaped LV is a marker of severe disease [3,78]. Patients with septal flattening generally have more advanced NYHA functional class and worse hemodynamics than those without. For instance, septal flattening on baseline echo/MRI has been associated with lower exercise capacity and higher likelihood of clinical worsening [79]. One study of severe TR patients found that those with a D-shaped LV (EI ≥ 1.2) had significantly worse survival than those without flattening [13]. Thus, it portends a poor prognosis if not corrected. In PH trials, a reduction in septal flattening (improvement in EI toward normal) is sometimes seen with effective therapy, correlating with improved output. Persistent or worsening D shape despite therapy might suggest the need for escalated treatment or transplant evaluation.

- Risk Stratification in Acute PE: The identification of septal bowing on a CT or echo in acute PE places the patient in a higher risk category. Guidelines for PE management consider signs of RV dysfunction as criteria for “submassive” PE (which may warrant thrombolytic therapy if there is evidence of myocardial injury). Septal bowing is significantly more common in patients with high-risk PE (p < 0.01) [80]. Patients with septal flattening on CT have been shown to be associated with all-cause mortality (p = 0.002), PE-related mortality (p = 0.0067), and adverse clinical outcomes (p = 0.0008) [81]. Clinically, if a radiologist reports a D-shaped LV on the PE CT, the treating team should be alerted that this is not a trivial PE. Additional monitoring, ICU-level care, or consideration of thrombolysis is necessary if no contraindications are indicated. The specificity of the sign means that a false positive is unlikely; so if it is there, one should act on it.

- Guide to Management: Seeing the Movahed sign can guide management decisions. In chronic RV overload scenarios, it may push clinicians to more aggressively manage pulmonary pressures or consider interventions. For example, in a patient with an ASD and signs of RV overload, it supports the case for ASD closure if not done, before irreversible PH develops. In a patient with CTEPH, a persistent D-shaped LV on therapy might prompt referral for pulmonary endarterectomy or balloon pulmonary angioplasty. In post-operative cardiac surgery patients, if a transesophageal echo shows a D-shaped LV, anesthesiologists may adjust ventilation or support to reduce RV afterload (such as administering pulmonary vasodilators like inhaled nitric oxide).

- Symptom Correlation: The sign itself does not cause symptoms, but it reflects the pathophysiology leading to symptoms. A D-shaped LV means the LV is being compressed, which can reduce LV preload and cardiac output. This can contribute to hypotension or exercise intolerance. Patients with acute septal flattening (e.g., in massive PE) often have cardiogenic shock because the LV underfills as the septum bulges into it [82]. In chronic cases, the D shape contributes to reduced LV stroke volume during exertion (as the interventricular dependence limits LV filling on inspiration). Therefore, it is often present in patients with syncope or near-syncope in the setting of PH [6,7,83]. Recognizing it can emphasize the need to limit exertion and start therapy.

- Monitoring Response to Therapy: In serial imaging, resolution of or improvement in the D shape can be a positive sign. For example, after pulmonary endarterectomy for CTEPH, a follow-up CT or MRI might show that the septum is now more normal in curvature, indicating reduced RV pressure and improved hemodynamics. Conversely, the development of a D-shaped LV on follow-up of a PH patient signals progression. It can, thus, be a visual aid in monitoring.

- Impact on Left Ventricular function: When the septum bows leftward, it impairs LV filling and distensibility. This can cause a drop in LV stroke volume and blood pressure, especially in acute settings. In chronic settings, the LV may adapt to a smaller end-diastolic volume over time (hence, many PH patients have relatively small LV cavities on imaging). The clinical implication is that therapies to unload the RV (diuretics, vasodilators) can paradoxically improve systemic output by allowing the LV to re-expand. It also means that in PH patients, part of their heart failure symptoms (fatigue, low output) is due to this interventricular interaction. Some advanced therapies (septostomy in PH) even intentionally create an ASD to allow the septum to shift and decompress the RV, trading off a right-to-left shunt for improved left filling, thus underscoring how critical the septal position is [84,85,86].

- Arrhythmias and Conduction: Chronic distortion of the septum can be a substrate for arrhythmias. While not directly an implication of the D shape, PH patients with septal flattening often have RV hypertrophy and dilation, which can lead to arrhythmias like atrial flutter or fibrillation [79,87,88,89]. The D-shaped septum itself on imaging might hint at underlying changes in myocardial fiber orientation and strain that could predispose to arrhythmias.

9. Limitations, Controversies, and Debates

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murarka, S.; Movahed, M.R. Review of Movahed’s sign (D shaped left ventricle seen on gated SPECT) suggestive of right ventricular overload. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 26, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahed, M.R.; Hepner, A.; Lizotte, P.; Milne, N. Flattening of the interventricular septum (D-shaped left ventricle) in addition to high right ventricular tracer uptake and increased right ventricular volume found on gated SPECT studies strongly correlates with right ventricular overload. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2005, 12, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudski, L.G.; Lai, W.W.; Afilalo, J.; Hua, L.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Louie, E.K.; Schiller, N.B. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 685–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyman, A.E.; Wann, S.; Feigenbaum, H.; Dillon, J.C. Mechanism of abnormal septal motion in patients with right ventricular volume overload: A cross-sectional echocardiographic study. Circulation 1976, 54, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestry, F.E.; Cohen, M.S.; Armsby, L.B.; Burkule, N.J.; Fleishman, C.E.; Hijazi, Z.M.; Lang, R.M.; Rome, J.J.; Wang, Y. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of Atrial Septal Defect and Patent Foramen Ovale: From the American Society of Echocardiography and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 910–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, E.K.; Rich, S.; Levitsky, S.; Brundage, B.H. Doppler echocardiographic demonstration of the differential effects of right ventricular pressure and volume overload on left ventricular geometry and filling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 19, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeije, R.; Badagliacca, R. The overloaded right heart and ventricular interdependence. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaraj, K.; Angjeliu, S.; Knopf, P.; Stadler, M.; Zbucki, K.; Kastrati, L.; Graf, S.; Gyöngyösi, M.; Hacker, M.; Calabretta, R. Case report: Myocardial perfusion gated-SPECT in pulmonary artery hypertension-the Movahed’s sign. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1168360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messroghli, D.R.; Bainbridge, G.J.; Alfakih, K.; Jones, T.R.; Plein, S.; Ridgway, J.P.; Sivananthan, M.U. Assessment of regional left ventricular function: Accuracy and reproducibility of positioning standard short-axis sections in cardiac MR imaging. Radiology 2005, 235, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.; Solaiyappan, M.B.; Tandri, H.; Bomma, C.; Genc, A.; Claussen, C.D.; Lima, J.A.C.; Bluemke, D.A. Right ventricle shape and contraction patterns and relation to magnetic resonance imaging findings. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2005, 29, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, Y.; Nagao, M.; Kamitani, T.; Yamanouchi, T.; Kawanami, S.; Yamamura, K.; Sakamoto, I.; Yabuuchi, H.; Honda, H. Clinical impact of left ventricular eccentricity index using cardiac MRI in assessment of right ventricular hemodynamics and myocardial fibrosis in congenital heart disease. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 3617–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, D.A.; Patel, S.S.; Mertens, L.; Friedberg, M.K.; Ivy, D.D. Relationship Between Left Ventricular Geometry and Invasive Hemodynamics in Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, T.; Maeda, M.; Kagawa, S.; Uno, G.; Rader, F.; Siegel, R.J.; Shiota, T. Impact of Diastolic Interventricular Septal Flattening on Clinical Outcome in Patients with Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.; Lustig, M.; Alley, M.T.; Murphy, M.J.; Vasanawala, S.S. Evaluation of valvular insufficiency and shunts with parallel-imaging compressed-sensing 4D phase-contrast MR imaging with stereoscopic 3D velocity-fusion volume-rendered visualization. Radiology 2012, 265, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Hahn, L.; Horowitz, M.; Kligerman, S.; Vasanawala, S.; Hsiao, A. Hemodynamic Assessment of Structural Heart Disease Using 4D Flow MRI: How We Do It. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 217, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmeneta Ulloa, J.; Álvarez Vázquez, A.; Martínez de Vega, V.; Cabrera, J.Á. Evaluation of Cardiac Shunts with 4D Flow Cardiac Magnetic Resonance: Intra- and Interobserver Variability. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 52, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarine, A.; Garçon, P.; Stansal, A.; Canepa, N.; Angelopoulos, G.; Silvera, S.; Sidi, D.; Marteau, V.; Zins, M. Four-dimensional Flow MRI: Principles and Cardiovascular Applications. Radiographics 2019, 39, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, J. 4D flow MRI applications in congenital heart disease. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, B.; Mollet, N.R.; Dymarkowski, S.; Rademakers, F.E.; Bogaert, J. Clinically suspected constrictive pericarditis: MR imaging assessment of ventricular septal motion and configuration in patients and healthy subjects. Radiology 2003, 228, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, B.; Quail, M.A.; Steeden, J.A.; McKee, A.; Odille, F.; Taylor, A.M.; Schulze-Neick, I.; Derrick, G.; Moledina, S.; Muthurangu, V. Real-time magnetic resonance assessment of septal curvature accurately tracks acute hemodynamic changes in pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeleveld, R.J.; Marcus, J.T.; Faes, T.J.C.; Gan, T.-J.; Boonstra, A.; Postmus, P.E.; Vonk-Noordegraaf, A. Interventricular septal configuration at mr imaging and pulmonary arterial pressure in pulmonary hypertension. Radiology 2005, 234, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, D.; García-Lunar, I.; Sierra, F.; Sánchez-Quintana, D.; Santiago, E.; Ballesteros, C.; Encalada, J.F.; Sánchez-González, J.; Fuster, V.; Ibáñez, B.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Characterization of Cardiac Adaptation and Myocardial Fibrosis in Pulmonary Hypertension Secondary to Systemic-To-Pulmonary Shunt. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e004566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, C.; Soler, R.; Rodriguez, E.; López, M.; Alvarez, L.; Fernández, N.; Montserrat, L. Magnetic resonance imaging of abnormal ventricular septal motion in heart diseases: A pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2011, 2, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zantonelli, G.; Cozzi, D.; Bindi, A.; Cavigli, E.; Moroni, C.; Luvarà, S.; Grazzini, G.; Danti, G.; Granata, V.; Miele, V. Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Prognostic Role of Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA). Tomography 2022, 8, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornenki, N.L.J.; Poorzargar, K.; Shanjer, M.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Delluc, A.; Crowther, M.; Siegal, D.M. Detection of right ventricular dysfunction in acute pulmonary embolism by computed tomography or echocardiography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2504–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Reddy, R.P.; Schoepf, U.J. Potential of right to left ventricular volume ratio measured on chest CT for the prediction of pulmonary hypertension: Correlation with pulmonary arterial systolic pressure estimated by echocardiography. Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jung, H.O.; Jung, J.I.; Kim, K.J.; Jeon, D.S.; Youn, H.J. CT-derived atrial and ventricular septal signs for risk stratification of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: Clinical associations of CT-derived signs for prediction of short-term mortality. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 30 (Suppl. 1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araoz, P.A.; Gotway, M.B.; Harrington, J.R.; Harmsen, W.S.; Mandrekar, J.N. Pulmonary embolism: Prognostic CT findings. Radiology 2007, 242, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaye, B.; Ghuysen, A.; Willems, V.; Lambermont, B.; Gerard, P.; D’ORio, V.; Gevenois, P.A.; Dondelinger, R.F. Severe pulmonary embolism:pulmonary artery clot load scores and cardiovascular parameters as predictors of mortality. Radiology 2006, 239, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, A.; Mirmomen, S.M.; Henry, T.S.; Kandathil, A.; Kelly, A.M.; King, C.S.; Kuzniewski, C.T.; Lai, A.R.; Lee, E.; Martin, M.D.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected Pulmonary Hypertension: 2022 Update. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2022, 19, S502–S512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, C.; Grosse, A. CT findings in diseases associated with pulmonary hypertension: A current review. Radiographics 2010, 30, 1753–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, G.; Cohen, D.; Steinvil, A.; Shmueli, H.; Keren, G.; Banai, S.; Berliner, S.; Rogowski, O. Significance of reflux of contrast medium into the inferior vena cava on computerized tomographic pulmonary angiogram. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahed, M.R. D-shaped left ventricle seen on gated single-photon emission computed tomography is suggestive of right ventricular overload: The so-called Movahed’s sign. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, B.H.; Collins, J.D.; François, C.J.; Barker, A.J.; Cuttica, M.J.; Chesler, N.C.; Markl, M.; Shah, S.J. MR and CT Imaging for the Evaluation of Pulmonary Hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palau-Caballero, G.; Walmsley, J.; Van Empel, V.; Lumens, J.; Delhaas, T. Why septal motion is a marker of right ventricular failure in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Mechanistic analysis using a computer model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 312, H691–H700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Veerdonk, M.C.; Roosma, L.; Trip, P.; Gopalan, D.; Noordegraaf, A.V.; Dorfmüller, P.; Nossent, E.J. Clinical-imaging-pathological correlation in pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 230144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omote, K.; Sorimachi, H.; Obokata, M.; Reddy, Y.N.V.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Omar, M.; DuBrock, H.M.; Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Pulmonary vascular disease in pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease: Pathophysiologic implications. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3417–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omary, M.S.; Sugito, S.; Boyle, A.J.; Sverdlov, A.L.; Collins, N.J. Pulmonary Hypertension Due to Left Heart Disease: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Therapy. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schena, M.; Clini, E.; Errera, D.; Quadri, A. Echo-Doppler evaluation of left ventricular impairment in chronic cor pulmonale. Chest 1996, 109, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, M.A.; Kiernan, M.S.; Bernstein, D.; Bozkurt, B.; Jacob, M.; Kapur, N.K.; Kociol, R.D.; Lewis, E.F.; Mehra, M.R.; Pagani, F.D.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Right-Sided Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e578–e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, W.; Adir, Y.; Barberà, J.A.; Champion, H.; Coghlan, J.G.; Cottin, V.; De Marco, T.; Galiè, N.; Ghio, S.; Gibbs, S.; et al. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62 (Suppl. 25), D109–D116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangiabadi, A.; De Pasquale, C.G.; Sajkov, D. Pulmonary hypertension and right heart dysfunction in chronic lung disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 739674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, H.; Kong, H. Computed tomography measurement of pulmonary artery for diagnosis of COPD and its comorbidity pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2015, 10, 2525–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, T.; Tanabe, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Shigeta, A.; Kawata, N.; Jujo, T.; Yanagawa, N.; Sakao, S.; Kasahara, Y.; Tatsumi, K. Role of 320-slice CT imaging in the diagnostic workup of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2013, 143, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, S.; Swift, A.J.; Capener, D.; Telfer, A.; Davies, C.; Hill, C.; Condliffe, R.; Elliot, C.; Hurdman, J.; Kiely, D.G.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced MR angiography and unenhanced proton MR imaging compared with CT pulmonary angiography in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurnicka, K.; Lichodziejewska, B.; Goliszek, S.; Dzikowska-Diduch, O.; Zdończyk, O.; Kozłowska, M.; Kostrubiec, M.; Ciurzyński, M.; Palczewski, P.; Grudzka, K.; et al. Echocardiographic Pattern of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Analysis of 511 Consecutive Patients. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlüer, E.E.; Senturk, G.Ö.; Karagöz, A.; Uyar, Y.; Bayata, S. Red flag in bedside echocardiography for acute pulmonary embolism: Remembering McConnell’s sign. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.A.; Lerakis, S.; Moreno, P.R. Right Ventricular Myocardial Infarction-A Tale of Two Ventricles: JACC Focus Seminar 1/5. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1779–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gara, P.T.; Kushner, F.G.; Ascheim, D.D.; Casey, D.E.; Chung, M.K.; de Lemos, J.A.; Ettinger, S.M.; Fang, J.C.; Fesmire, F.M.; Franklin, B.A.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, e78–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, M.A.; Anwar, S.; Broberg, C.; Browne, L.; Chung, T.; Johnson, T.; Muthurangu, V.; Taylor, M.; Valsangiacomo-Buechel, E.; Wilhelm, C. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance/European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging/American Society of Echocardiography/Society for Pediatric Radiology/North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging Guidelines for the use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in pediatric congenital and acquired heart disease: Endorsed by The American Heart Association. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2022, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.B.; Foster, E.; Kuehl, K.; Alpert, J.; Brabeck, S.; Crumb, S.; Davidson, W.R.; Earing, M.G.; Ghoshhajra, B.B.; Karamlou, T.; et al. Congenital heart disease in the older adult: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 131, 1884–1931, Erratum in Circulation 2015, 131, e510. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerbaum, P.; Körperich, H.; Esdorn, H.; Blanz, U.; Barth, P.; Hartmann, J.; Gieseke, J.; Meyer, H. Atrial septal defects in pediatric patients: Noninvasive sizing with cardiovascular MR imaging. Radiology 2003, 228, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, T.P., Jr.; Atwood, G.F.; Boucek, R.J., Jr.; Cordell, D.; Boerth, R.C. Right ventricular volume characteristics in ventricular septal defect. Circulation 1976, 54, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, Y.; Fukushige, J.; Ueda, K. Congestive heart failure during early infancy in patients with ventricular septal defect relative to early closure. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1996, 17, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, K.K.; Daniels, C.J.; Aboulhosn, J.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Broberg, C.S.; Colman, J.M.; Crumb, S.R.; Dearani, J.A.; Fuller, S.; Gurvitz, M.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, e81–e192, Erratum in J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2361–2362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.018.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, M.; Browne, L.P.; Jaggers, J.; Barker, A.J.; Morgan, G.J.; Ivy, D.D.; Mitchell, M.B. Abnormal left ventricular flow organization following repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, T.; Wald, R.M.; Bucholz, E.; Cnota, J.F.; McElhinney, D.B.; Mercer-Rosa, L.M.; Mery, C.M.; Miles, A.L.; Moore, J. On behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing Long-Term Management of Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Dysfunction in Repaired Tetralogy of Fallot: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e689–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Sheehan, F.H.; Bouzas, B.; Chen, S.S.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Kilner, P.J. The shape and function of the right ventricle in Ebstein’s anomaly. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratz, S.; Janello, C.; Müller, D.; Seligmann, M.; Meierhofer, C.; Schuster, T.; Schreiber, C.; Martinoff, S.; Hess, J.; Kühn, A.; et al. The functional right ventricle and tricuspid regurgitation in Ebstein’s anomaly. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoara, A.; Skubas, N.; Ad, N.; Finley, A.; Hahn, R.T.; Mahmood, F.; Mankad, S.; Nyman, C.B.; Pagani, F.; Porter, T.R.; et al. Guidelines for the Use of Transesophageal Echocardiography to Assist with Surgical Decision-Making in the Operating Room: A Surgery-Based Approach: From the American Society of Echocardiography in Collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 692–734, Erratum in J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 1426. 10.1016/j.echo.2020.08.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamruddin, S.; Alkharabsheh, S.K.; Sato, K.; Kumar, A.; Cremer, P.C.; Chetrit, M.; Johnston, D.R.; Klein, A.L. Differentiating Constriction from Restriction (from the Mayo Clinic Echocardiographic Criteria). Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repessé, X.; Charron, C.; Vieillard-Baron, A. Acute cor pulmonale in ARDS: Rationale for protecting the right ventricle. Chest 2015, 147, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessap, A.M.; Boissier, F.; Charron, C.; Bégot, E.; Repessé, X.; Legras, A.; Brun-Buisson, C.; Vignon, P.; Vieillard-Baron, A. Acute cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: Prevalence, predictors, and clinical impact. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissier, F.; Katsahian, S.; Razazi, K.; Thille, A.W.; Roche-Campo, F.; Leon, R.; Vivier, E.; Brochard, L.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Brun-Buisson, C.; et al. Prevalence and prognosis of cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legras, A.; Caille, A.; Begot, E.; Lhéritier, G.; Lherm, T.; Mathonnet, A.; Frat, J.-P.; Courte, A.; Martin-Lefèvre, L.; Gouëllo, J.-P.; et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-associated acute cor pulmonale and patent foramen ovale: A multicenter noninvasive hemodynamic study. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrard, B.; Woillard, J.-B.; Legras, A.; Bouaoud, M.; Gourraud, M.; Humeau, A.; Goudelin, M.; Vignon, P. Diagnostic, prognostic and clinical value of left ventricular radial strain to identify paradoxical septal motion in ventilated patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome: An observational prospective multicenter study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Evrard, B.; Prat, G.; Chew, M.S.; Balik, M.; Clau-Terré, F.; De Backer, D.; Dessap, A.M.; Orde, S.; et al. Echocardiography phenotypes of right ventricular involvement in COVID-19 ARDS patients and ICU mortality: Post-hoc (exploratory) analysis of repeated data from the ECHO-COVID study. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, J.; Huntjens, P.R.; Prinzen, F.W.; Delhaas, T.; Lumens, J. Septal flash and septal rebound stretch have different underlying mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016, 310, H394–H403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalen, J.M.; Remme, E.W.; Larsen, C.K.; Andersen, O.S.; Krogh, M.; Duchenne, J.; Hopp, E.; Ross, S.; Beela, A.S.; Kongsgaard, E.; et al. Mechanism of Abnormal Septal Motion in Left Bundle Branch Block: Role of Left Ventricular Wall Interactions and Myocardial Scar. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 2402–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossone, E.; Duong-Wagner, T.H.; Paciocco, G.; Oral, H.; Ricciardi, M.; Bach, D.S.; Rubenfire, M.; Armstrong, W.F. Echocardiographic features of primary pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 1999, 12, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciancalepore, M.A.; Maffessanti, F.; Patel, A.R.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Chandra, S.; Freed, B.H.; Caiani, E.G.; Lang, R.M.; Mor-Avi, V. Three-dimensional analysis of interventricular septal curvature from cardiac magnetic resonance images for the evaluation of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 28, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons Kroeker, C.A.; Adeeb, S.; Tyberg, J.V.; Shrive, N.G. A 2D FE model of the heart demonstrates the role of the pericardium in ventricular deformation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H2229–H2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.S.; Sayed-Ahmed, E.Y.; Kroeker, C.A.G.; Sun, Y.-H.; Ter Keurs, H.E.D.J.; Shrive, N.G.; Tyberg, J.V. Compression of interventricular septum during right ventricular pressure loading. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 280, H2639–H2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beenen, L.F.M.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Stoker, J.; Middeldorp, S. Prognostic value of cardiovascular parameters in computed tomography pulmonary angiography in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1702611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.K.; Thilo, C.; Schoepf, U.J.; Barraza, J.M.; Nance, J.W.; Bastarrika, G.; Abro, J.A.; Ravenel, J.G.; Costello, P.; Goldhaber, S.Z. CT signs of right ventricular dysfunction: Prognostic role in acute pulmonary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Choi, S.I.; Chun, E.J.; Choi, S.H.; Park, J.H. The Cardiac MR Images and Causes of Paradoxical Septal Motion. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 2010, 62, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.K.; Ramos-Duran, L.; Schoepf, U.J.; Armstrong, A.M.; Abro, J.A.; Ravenel, J.G.; Thilo, C. Reproducibility of CT signs of right ventricular dysfunction in acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 194, 1500–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishiki, K.; Singh, A.; Narang, A.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Goyal, N.; Maffessanti, F.; Besser, S.A.; Mor-Avi, V.; Lang, R.M.; Addetia, K. Impact of Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on the Left Heart and Prognostic Implications. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.; Guihaire, J.; Skhiri, M.; Denault, A.Y.; Mercier, O.; Al-Halabi, S.; Vrtovec, B.; Fadel, E.; Zamanian, R.T.; Schnittger, I. Septal curvature is marker of hemodynamic, anatomical, and electromechanical ventricular interdependence in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Echocardiography 2014, 31, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayganfar, A.; Hajiahmadi, S.; Astaraki, M.; Ebrahimian, S. The assessment of acute pulmonary embolism severity using CT angiography features. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinel, F.G.; Nance, J.W.; Schoepf, U.J.; Hoffmann, V.S.; Thierfelder, K.M.; Costello, P.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Bamberg, F. Predictive Value of Computed Tomography in Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 747–759.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.B.; Giri, J.; Kobayashi, T.; Ruel, M.; Mittnacht, A.J.; Rivera-Lebron, B.; DeAnda, A.; Moriarty, J.M.; MacGillivray, T.E. Surgical Management and Mechanical Circulatory Support in High-Risk Pulmonary Embolisms: Historical Context, Current Status, and Future Directions: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e628–e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.T.-J.; Lankhaar, J.-W.; Marcus, J.T.; Westerhof, N.; Marques, K.M.; Bronzwaer, J.G.F.; Boonstra, A.; Postmus, P.E.; Vonk-Noordegraaf, A. Impaired left ventricular filling due to right-to-left ventricular interaction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H1528–H1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeken, Y.; Kuijpers, N.H.; Lumens, J.; Arts, T.; Delhaas, T. Atrial septostomy benefits severe pulmonary hypertension patients by increase of left ventricular preload reserve. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H2654–H2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoun, P.M. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2361–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maluli, H.; DeStephan, C.M.; Alvarez, R.J., Jr.; Sandoval, J. Atrial Septostomy: A Contemporary Review. Clin. Cardiol. 2015, 38, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Ruetzler, K.; Ghadimi, K.; Horn, E.M.; Kelava, M.; Kudelko, K.T.; Moreno-Duarte, I.; Preston, I.; Bovino, L.L.R.; Smilowitz, N.R.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension in Noncardiac Surgery: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, 1317–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Rudski, L.G.; Addetia, K.; Afilalo, J.; D’aLto, M.; Freed, B.H.; Friend, L.B.; Gargani, L.; Grapsa, J.; Hassoun, P.M.; et al. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults and Special Considerations in Pulmonary Hypertension: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2025, 38, 141–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logantha, S.J.R.J.; Yamanushi, T.T.; Absi, M.; Temple, I.P.; Kabuto, H.; Hirakawa, E.; Quigley, G.; Zhang, X.; Gurney, A.M.; Hart, G.; et al. Remodelling and dysfunction of the sinus node in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, M.M.; Steinmann, B.; Scherkamp, T.; Arnold, M.B.; Achenbach, S.; Marwan, M. Analysis of left ventricular function, left ventricular outflow tract and aortic valve area using computed tomography: Influence of reconstruction parameters on measurement accuracy. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, D.; Mori, S.; Izawa, Y.; Toh, H.; Suzuki, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Toba, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Tanaka, H.; Watanabe, Y.; et al. Diversity and determinants of the sigmoid septum and its impact on morphology of the outflow tract as revealed using cardiac computed tomography. Echocardiography 2022, 39, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciniak, M.; Gilbert, A.; Loncaric, F.; Fernandes, J.F.; Bijnens, B.; Sitges, M.; King, A.; Crispi, F.; Lamata, P. Septal curvature as a robust and reproducible marker for basal septal hypertrophy. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age/Gender | Imaging Modality | Key Findings | Clinical Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61/Male | Cardiac MRI | Flattened or left-bowing septum during diastole; eccentricity index abnormal | Severe idiopathic pulmonary hypertension [23] |

| 38/Female | Cardiac MRI | Enlarged RV, leftward bowing of ventricular septum | Atrial septal defect [23] |

| 15/Female | Cardiac MRI | Crescentic LV with leftward septal bowing in systole; D-shape during systemic stress | Dextrose-transposition of the great arteries post atrial switch (chronic RV pressure overload) [23] |

| 24/Female | Cardiac MRI | Leftward septal bowing of the right ventricle, which was accentuated during systole | Tricuspid regurgitation [23] |

| 42/Female | Cardiac MRI | Flattening/leftwards septal bowing during diastole | Pulmonary regurgitation [23] |

| 18/Male | Cardiac MRI | Hypertrophied right ventricle and septal leftwards bowing during early diastole | severe idiopathic pulmonary hypertension [23] |

| 60/Male | Cardiac MRI | Inspiratory septal bowing during early diastole | Inflammatory pericarditis [23] |

| 48/Male | Cardiac MRI | Leftwards septal shift during early systole and normal configuration of the interventricular septum at end diastole | Myocardial infarction and left branch block bundle [23] |

| 21/Male | Cardiac MRI | Early systolic leftward septal motion and the sustained leftward motion during mid-late systole | Complete repair of tetralogy of Fallot [76] |

| 35/Female | Cardiac MRI | Systolic anterior motion of the ventricular septum parallel to the posterior wall of the left ventricle with enlargement of the right ventricle | Sinus venous type ASD with moderate volume overload [76] |

| 57/Male | Cardiac MRI | Diastolic flattening of the septal wall | Pulmonary thromboembolism [76] |

| 63/Male | Cardiac MRI | Early diastolic septal flattening | Mitral stenosis [76] |

| 54/Female | Cardiac MRI | Early diastolic septal flattening | Constrictive pericarditis [76] |

| 63/Male | Cardiac MRI | Septum in early systole adopts a more inner position compared to that in end systole | Left bundle branch block [76] |

| 57/Female | Cardiac CT | Four-chamber view shows septal bowing convex toward left ventricle | Pulmonary thromboembolism [77] |

| 77/Female | Cardiac CT | Four-chamber view shows septal flattening | Pulmonary thromboembolism [75] |

| 69/Male | Cardiac CT | Four-chamber view shows septal bowing convex toward the left ventricle | Pulmonary thromboembolism [75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCoy, D.; Movahed, M.R. Review of D-Shape Left Ventricle Seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT), Similar to the Movahed Sign Seen on Cardiac Gated Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as an Indicator for Right Ventricular Overload. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176041

McCoy D, Movahed MR. Review of D-Shape Left Ventricle Seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT), Similar to the Movahed Sign Seen on Cardiac Gated Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as an Indicator for Right Ventricular Overload. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176041

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCoy, Daniel, and Mohammad Reza Movahed. 2025. "Review of D-Shape Left Ventricle Seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT), Similar to the Movahed Sign Seen on Cardiac Gated Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as an Indicator for Right Ventricular Overload" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176041

APA StyleMcCoy, D., & Movahed, M. R. (2025). Review of D-Shape Left Ventricle Seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT), Similar to the Movahed Sign Seen on Cardiac Gated Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as an Indicator for Right Ventricular Overload. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176041