Pediatric Drug Poisoning in Vojvodina, Serbia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical and Toxicological Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data and Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

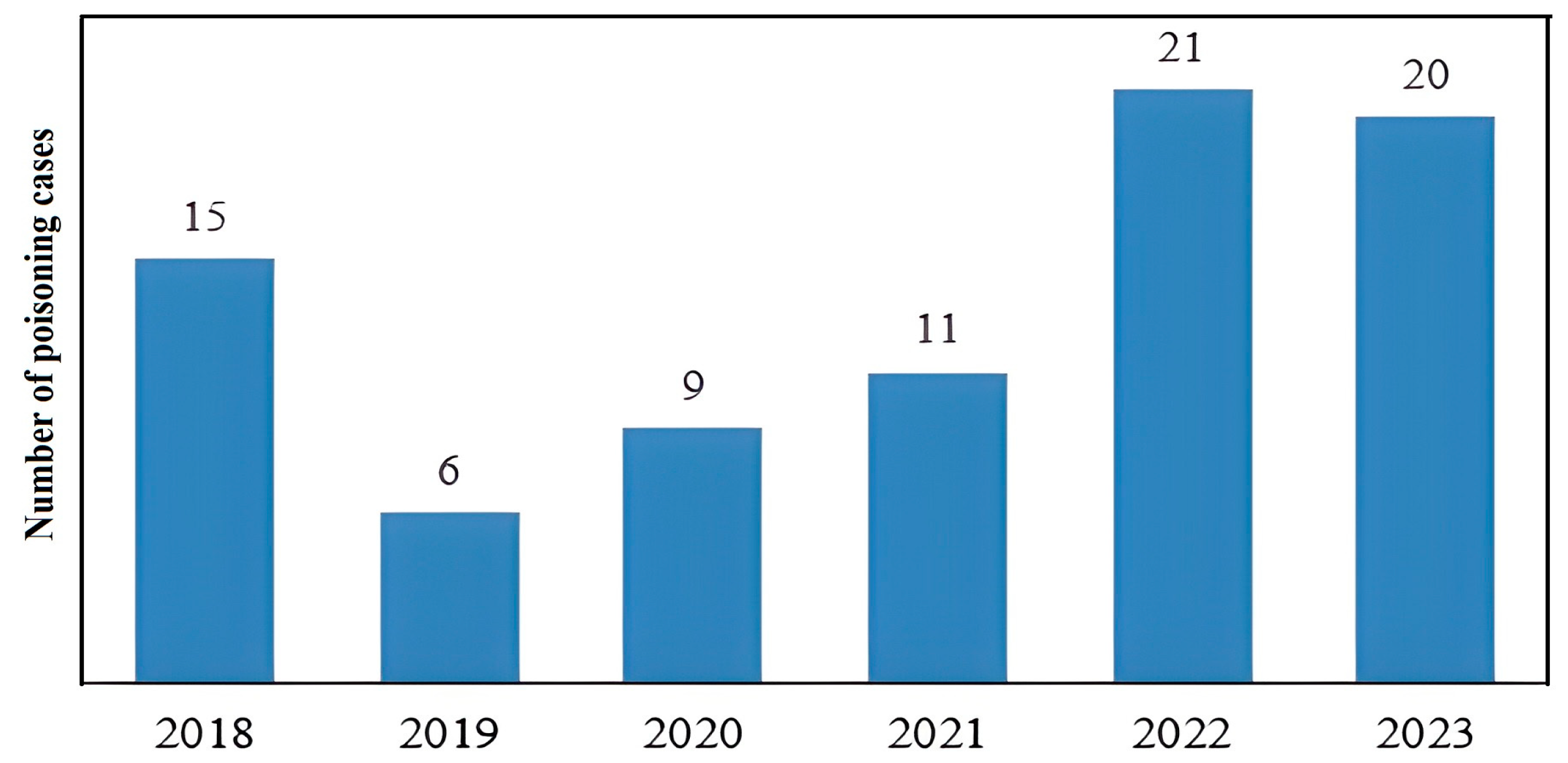

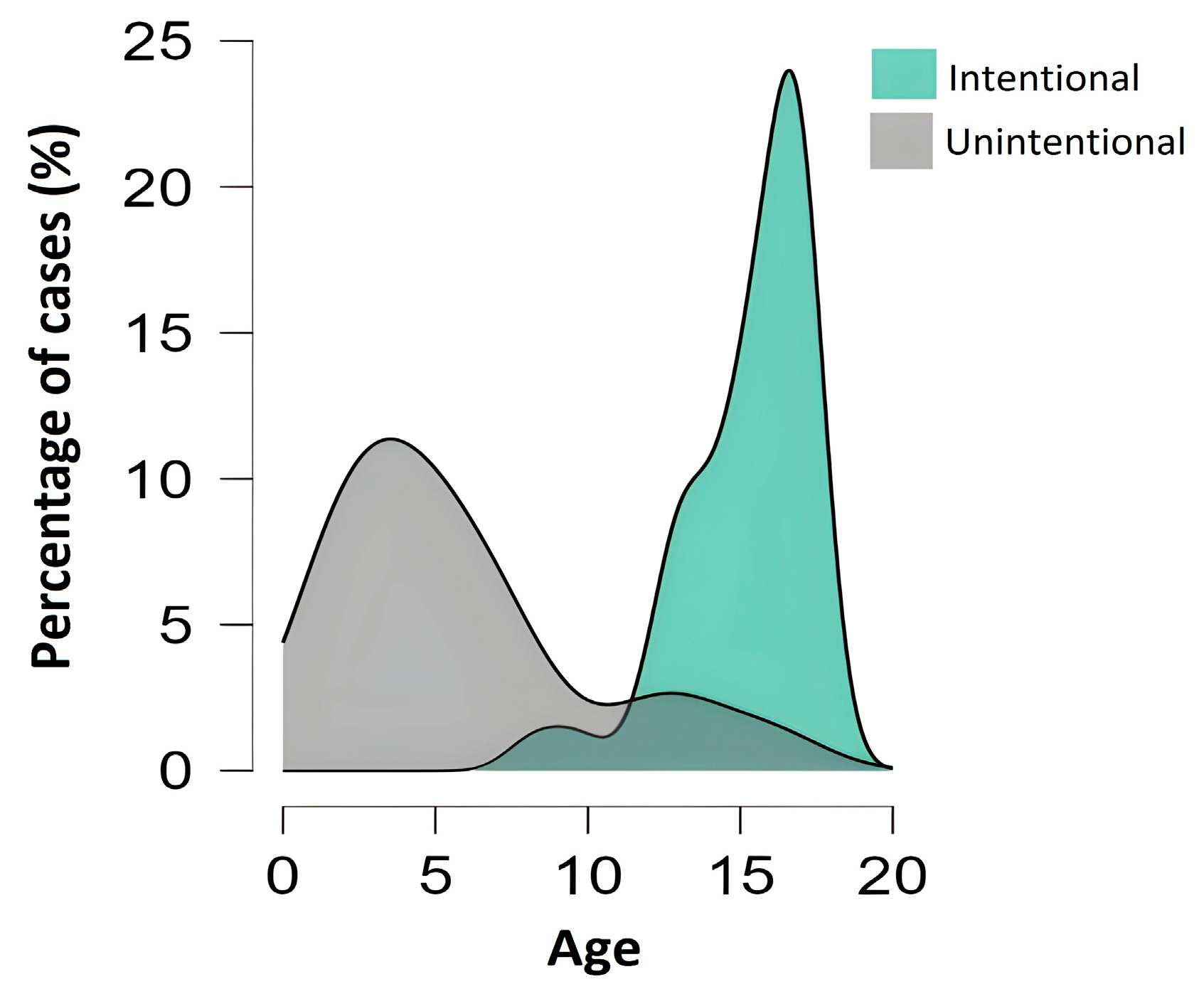

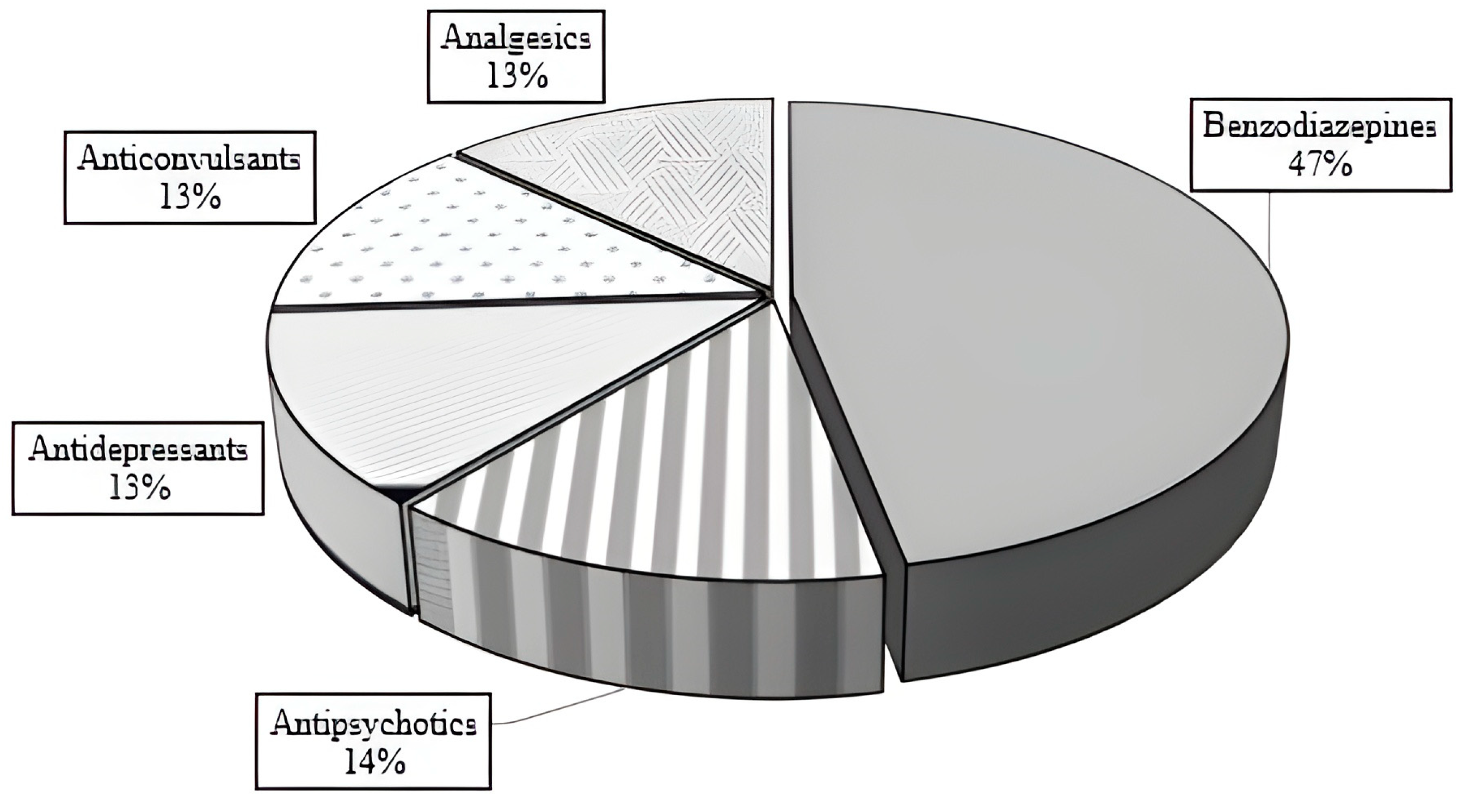

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MMA | Military Medical Academy |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| PSS | Poisoning Severity Score |

| SSRIs | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Ozan, E.; Öztürk, S.; Çağlar, A. Retrospective analysis of the pediatric intoxication cases. Trends Pediatr. 2022, 3, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, İ.; Akın, Y.; Yücel, M.; Yaykıran, D. Evaluation of children and adolescent cases admitted to the pediatric emergency department for drug intoxication. Evaluation 2021, 8, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soave, P.M.; Curatola, A.; Ferretti, S.; Raitano, V.; Conti, G.; Gatto, A.; Chiaretti, A. Acute poisoning in children admitted to pediatric emergency department: A five-years retrospective analysis. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022004. [Google Scholar]

- Academy, M.M. Annual Report of the National Poison Control Centre. Available online: http://www.vma.mod.gov.rs/sr-lat/specijalnosti/centri/nacionalni-centar-za-kontrolu-trovanja/godisnjak-NCKT (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Katić, K.; Stojadinović, A.; Mijatović, V.; Grujić, M. Acute poisoning in children and adolescents hospitalized at the Institute of Child and Youth Health Care of Vojvodina between 2015–2017. Med. Pregl. 2019, 72, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, D.; Petrović-Tepić, S.; Knežević, D.; Tepić, A.; Burgić, S.; Radmanović, V.; Burgić-Radmanović, M. Characteristics of unintentional injuries in hospitalised children and adolescents-national retrospective study. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2023, 1, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancic, N.; Rankovic, A.; Savic, D.; Abramovic, A.; Rancic, J.; Jakovljevic, M. Intentional self-poisonings and unintentional poisonings of adolescents with nonfatal outcomes. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 2015, 24, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, C.E.; Văruț, R.-M.; Singer, M.; Cosoveanu, S.; Abdul Razzak, J.; Popescu, M.E.; Gaman, S.; Petrescu, I.O.; Popescu, C. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Pediatric Acute Drug Intoxications: A Retrospective Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlade-Andrei, M.; Nedelea, P.L.; Ionescu, T.D.; Rosu, T.S.; Hauta, A.; Grigorasi, G.R.; Blaga, T.; Sova, I.; Popa, O.T.; Cimpoesu, D. Pediatric Emergency Department Management in Acute Poisoning—A 2-Year Retrospective Study. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosiorek, D.; Lewko, J.; Romankiewicz, E. Children Intoxicated with Psychoactive Substances: The Health Status on Admission to Hospital Based on Medical Records. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Luo, F. Examining Drug Poisoning in Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Patients: Clinical Analysis and Pharmacy Services. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1507639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonen, I.M.J.; Rietjens, S.J.; van Velzen, A.G.; de Lange, D.W.; Koppen, A. Risk Factors for Deliberate Self-Poisoning among Children and Adolescents in The Netherlands. Clin. Toxicol. 2024, 62, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Cha, Y.S.; Yeon, S.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, Y.; Choi, J.-G.; Cha, K.-C.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, H. Changes in diagnosis of poisoning in patients in the emergency room using systematic toxicological analysis with the National Forensic Service. J. Korean Med Sci. 2021, 36, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, B.R.; Sutheimer, C.A.; Sunshine, I. Role of the toxicology laboratory in the treatment of acute poisoning. Med. Toxicol. 1986, 1, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, B.; Sutheimer, C.; Sunshine, I. Role of the toxicology laboratory in suspected ingestions. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 1986, 33, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K. Stages of adolescence. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Brown, B.B., Prinstein, M.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 360–368. [Google Scholar]

- Abantanga, F.A.; Jackson, S.R.; Upperman, J.S. Initial assessment and resuscitation of the trauma patient. In Paediatric Surgery: A Comprehensive Text for Africa; Ameh, E.A., Bickler, S.W., Lakhoo, K., Nwomeh, B.C., Poenaru, D., Eds.; Global HELP Organization: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Orfanidis, A.; Krokos, A.; Mastrogianni, O.; Gika, H.; Raikos, N.; Theodoridis, G. Development and validation of a single step GC/MS method for the determination of 41 drugs and drugs of abuse in postmortem blood. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.E.; Sjöberg, G.K.; Haines, J.A.; Pronczuk de Garbino, J. Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, N.; El-Saeed, N.B.; Elbadri, N. Acute child poisoning and its related risk factors during the COVID era. Egypt. J. Forensic Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelló, M.; Rio-Aige, K.; Rius, P.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Changes in prescription drug abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic evidenced in the Catalan pharmacies. Public Health Front. 2023, 11, 1116337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maertens, A.; Golden, E.; Luechtefeld, T.H.; Hoffmann, S.; Tsaioun, K.; Hartung, T. Probabilistic risk assessment–the keystone for the future of toxicology. Altex 2022, 39, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitman, A.; Park, H.-D.; Fitzgerald, R.L. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: A review. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2014, 38, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Schmoldt, A.; Andresen-Streichert, H.; Iwersen-Bergmann, S. Revisited: Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of more than 1100 drugs and other xenobiotics. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, F.; Bailey, B.; Bratton, S.L. Hospitalizations for pediatric intoxication in Washington State, 1987–1997. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalova, P.; Buchta, M.; Drietomska, V.; Spicakova, A.; Wawruch, M.; Ondra, P.; Urbanek, K. Acute drug intoxication in childhood: A 10-year retrospective observational single-centre study and case reports. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2023, 167, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo Brunello, G.C.; Frizon Alfieri, D.; Molino Guidoni, C.; Girotto, E. Factors Associated with the Severity of Suicide Attempts by Poisoning in Adolescents. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2024, 10, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaylan, N.; Yalçın, S.S.; Tezel, B.; Aydın, Ş.; Özen, Ö.; Şengelen, M.; Çakır, B. Evaluation of Injury-Related Under-Five Mortality in Turkey between 2014–2017. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2021, 63, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferranti, S.; Grande, E.; Gaggiano, C.; Grosso, S. Antiepileptic drugs: Role in paediatric poisoning. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; AlJamal, A.N.; Mohamed Ibrahim, M.I.; Salameh, K.; AlYafei, K.; Abu Zaineh, S.; Adheir, F.S.S. Poisoning emergency visits among children: A 3-year retrospective study in Qatar. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamireau, T.; Llanas, B.; Kennedy, A.; Fayon, M.; Penouil, F.; Favarell-Garrigues, J.C.; Demarquez, J.L. Epidemiology of poisoning in children: A 7-year survey in a paediatric emergency care unit. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2002, 9, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, G.N.; Di Scipio, F.; Bosetti, F.M.; Mognetti, B.; Romano, F.; Carere, M.E.; Del Giudice, A.C.; Castagno, E.; Bondone, C.; Urbino, A.F. Childhood acute poisoning in the Italian North-West area: A six-year retrospective study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyu, M.; Atış, Ş.K. Retrospective evaluation of intoxication cases followed in pediatric intensive care: A 5-year experience. Haydarpasa Numune Med. J. 2020, 60, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samardžić, J.; Stevanović, A.; Jančić, J.; Dimitrijević, I. (Zlo)upotreba i adiktivni potencijal benzodiazepina—Analiza potrošnje u Srbiji u periodu 2014–2016. Engrami 2018, 40, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.B.; Krenzelok, E.P. Paroxetine (Paxil) overdose: A pediatric focus. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 1997, 39, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xuev, S.; Ickowicz, A. Serotonin Syndrome in Children and Adolescents Exposed to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors—A Review of Literature. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Schwartz, W.; Benson, B.E.; Lee, S.C.; Litovitz, T. Comparison of citalopram and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor ingestions in children. Clin. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, K.; Poel, K.; Pennington, S.; Bindseil, I.; Banerji, S.; Leonard, J.; Wang, G.S. Trends of prescription psychotropic medication exposures in pediatric patients, 2009–2018. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 60, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanaty, A.W.; El-Kawy Abou Hatab, H.; Girgis, N.F.; Zaher Amin, S.A.; El-Hady Hammad, S.A. Evaluation of acute antipsychotic poisoned cases. Menoufia Med. J. 2016, 29, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak, M.; Madah, E.E.; Gharbawy, D.E.; Ashmawy, M. Assessment of Acute Antipsychotic Poisoned Cases Admitted to Tanta University Poison Control Unit. Ain-Shams J. Forensic Med. Clin. Toxicol. 2019, 33, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, M.; Rauber-Lüthy, C.; Hoffmann-Walbeck, P.; Reinecke, H.-J.; Prasa, D.; Stedtler, U.; Färber, E.; Genser, D.; Kupferschmidt, H.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; et al. Atypical antipsychotic poisoning in young children: A multicentre analysis of poisons centres data. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014, 173, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gazarian, M.; Verjee, Z.H.; Johnson, D. Acute renal insufficiency in ibuprofen overdose. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 1995, 11, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejo Menor, J.L.; Lallana Duplá, M.T. Intoxicaciones por antitérmicos. An. Esp. Pediatr. 2002, 56, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaswa, R. An approach to the management of acute poisoning in emergency settings. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2024, 66, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampp, C.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Budnitz, D.S.; Mathew, J.; Ho, A.; McAninch, J. The role of unit-dose child-resistant packaging in unintentional childhood exposures to buprenorphine–naloxone tablets. Drug Saf. 2020, 43, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, G.K.; Subramaniam, B.; Veeranna, B. Standards of Child Resistant Packaging: A Regulatory View. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2024, 58, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowki, J.; Czapla, M.; Konop, M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Rosińczuk, J. Evaluation of Accidental and Intentional Pediatric Poisonings: Retrospective Analysis of Emergency Medical Service Interventions in Wroclaw, Poland. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansori, K.; Soori, H.; Farnaghi, F.; Khodakarim, S.; Khodadost, M. A case-control study on risk factors for unintentional childhood poisoning in Tehran. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2016, 30, 355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ćurčić, V. Mental health of adolescents: Risk and chance. Psihijatr. Danas 2005, 37, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

| All Cases | Children (<10 Years) | Adolescents (10–17 Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 82 | 17 (21%) | 65 (79%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 23 (28%) | 9 (53%) | 15 (23%) |

| Female | 59 (72%) | 8 (47%) | 50 (77%) |

| Age (year; IQR) | |||

| Median | 4.5 (4.75) | 16 (3) | |

| Manner of poisoning | |||

| Intentional | 64 (78%) | 2 (2%) | 62 (95%) |

| Unintentional | 18 (22%) | 15 (88%) | 3 (5%) |

| Area | |||

| City | 53 (64%) | 8 (47%) | 45 (69%) |

| Rural | 29 (36%) | 9 (53%) | 20 (31%) |

| Repeated poisonings | |||

| No | 67 (82%) | 17 (100%) | 49 (76%) |

| Yes | 15 (18%) | NR | 15 (24%) |

| Cause of poisoning | |||

| Suicide attempt | 29 (34%) | NR | 29 (45%) |

| Conflict in the family | 26 (31%) | 1 (6%) | 25 (38%) |

| Peer violence | 9 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (12%) |

| Unintentional | 18 (22%) | 15 (88%) | 3 (5%) |

| All Cases | Children (<10 Years) | Adolescents (10–17 Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning Severity Score | |||

| 1 | 64 (78%) | 13 (76%) | 51 (78%) |

| 2 | 11 (13%) | 3 (18%) | 8 (12%) |

| 3 | 7 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 6 (10%) |

| Number of ingested substances | |||

| 1 | 56 (68%) | 13 (76%) | 42 (66%) |

| 2 | 16 (19%) | 3 (18%) | 13 (20%) |

| 3 | 10 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 9 (14%) |

| Is there an alignment between patient-reported drug exposure and toxicological analysis results? | |||

| Yes | 53 (59%) | 7 (41%) | 46 (72%) |

| No | 29 (41%) | 10 (59%) | 18 (28%) |

| n | Cmedian (µg/mL) | Minimum | Maximum | LOD (µg/mL) | LOQ (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromazepam | 20 | 0.095 | 0.010 | 0.689 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Diazepam | 15 | 0.202 | 0.061 | 0.891 | 0.022 | 0.060 |

| Ibuprofen | 9 | 1.784 | 0.262 | 8.277 | 0.172 | 0.250 |

| Carbamazepine | 8 | 9.789 | 2.432 | 33.44 | 0.458 | 1.520 |

| Sertraline | 6 | 0.186 | 0.023 | 1.855 | 0.001 | 0.012 |

| Lorazepam | 5 | 0.044 | 0.065 | 0.075 | 0.005 | 0.060 |

| Paracetamol | 3 | 1.478 | 0.120 | 1.905 | 0.010 | 0.100 |

| Clonazepam | 3 | 0.037 | 0.034 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Haloperidol | 2 | 0.042 | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Citalopram | 2 | 0.099 | 0.012 | 0.186 | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| Lamotrigine | 2 | 10.28 | 10.80 | 12.74 | 0.263 | 1.200 |

| Fluoxetine | 1 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.005 | 0.017 |

| Benzodiazepines | Antidepressants | Antipsychotics | Anticonvulsants | Analgesics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 43 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 |

| Poisoning Severity Score | |||||

| 1 | 39 (91%) | 9 (76%) | 9 (69%) | 6 (50%) | 10 (84%) |

| 2 | 3 (7%) | 2 (16%) | 3 (23%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) |

| 3 | 1 (2%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) | 4 (33%) | 1 (8%) |

| Clinical manifestation | |||||

| Adynamia | 12 (28%) | 3 (25%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) |

| Sleepiness | 19 (44%) | 1 (8%) | 3 (23%) | 2 (17%) | 3 (25%) |

| Unconsciousness | 5 (12%) | 4 (33%) | 6 (46%) | 6 (50%) | 1 (8%) |

| Nausea | 5 (12%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (32%) | 2 (17%) | 8 (67%) |

| Consciousness | |||||

| Coma | 2 (5%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) | 6 (50%) | 2 (17%) |

| Somnolence | 7 (16%) | 1 (8%) | 3 (23%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) |

| Conscious | 34 (79%) | 9 (75%) | 9 (69%) | 4 (33%) | 9 (75%) |

| Vital parameters | |||||

| Tachycardia | 23 (53%) | 10 (83%) | 10 (77%) | 8 (67%) | 7 (58%) |

| Bradycardia | 4 (9%) | NR | 1 (8%) | NR | 2 (17%) |

| Hypertension | NR | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) | NR | 1 (8%) |

| Hypotension | 19 (44%) | 3 (25%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (33%) | 5 (42%) |

| Tachypnea | 10 (23%) | 2 (17%) | 4 (31%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (33%) |

| Bradypnea | 3 (7%) | NR | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baljak, J.; Stojadinović, A.; Zečević, D.; Đurendić-Brenesel, M.; Ajduković, N.; Vapa, D.; Poparić, M.; Strilić, D.; Tomić, N.; Rašković, A. Pediatric Drug Poisoning in Vojvodina, Serbia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical and Toxicological Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175967

Baljak J, Stojadinović A, Zečević D, Đurendić-Brenesel M, Ajduković N, Vapa D, Poparić M, Strilić D, Tomić N, Rašković A. Pediatric Drug Poisoning in Vojvodina, Serbia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical and Toxicological Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175967

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaljak, Jovan, Aleksandra Stojadinović, Dragan Zečević, Maja Đurendić-Brenesel, Nikša Ajduković, Dušan Vapa, Miljana Poparić, David Strilić, Nataša Tomić, and Aleksandar Rašković. 2025. "Pediatric Drug Poisoning in Vojvodina, Serbia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical and Toxicological Assessment" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175967

APA StyleBaljak, J., Stojadinović, A., Zečević, D., Đurendić-Brenesel, M., Ajduković, N., Vapa, D., Poparić, M., Strilić, D., Tomić, N., & Rašković, A. (2025). Pediatric Drug Poisoning in Vojvodina, Serbia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical and Toxicological Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14175967