Management of Subsequent Pregnancy After Perinatal Death: Results from the UNSURENESS Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis and Data Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Professional Experience

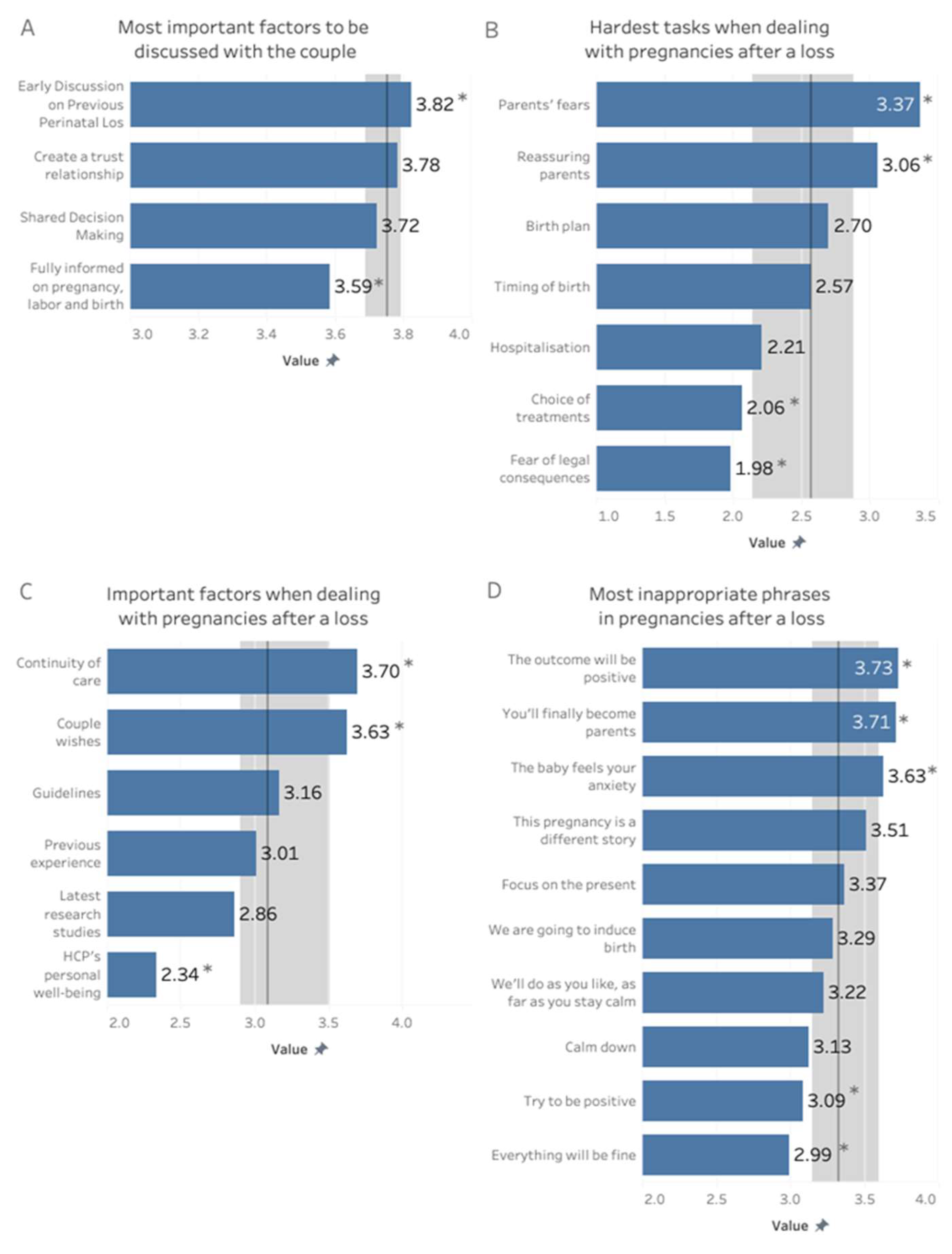

3.3. Management of Pregnancies After a Loss

3.3.1. Multidisciplinarity

3.3.2. Shared Decision Making

3.3.3. Clinical Management of Pregnancies After a Loss

3.3.4. Labor and Birth Management

3.3.5. Information and Psychological Aspects

3.3.6. Easy and Difficult Aspects in Assisting Pregnancies After Perinatal Loss

- Easier Aspects of Care

- More Difficult Aspects of Care

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Stillbirths and Stillbirth Rates. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/stillbirths/ (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- UNICEF. Neonatal Mortality. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality/ (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- EpiCentro. Stillbirth, I Dati 2019. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/materno/stillbirth-report-2020 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Wojcieszek, A.; Boyle, F.M.; Belizán, J.M.; Cassidy, J.; Cassidy, P.; Erwich, J.J.M.; Farrales, L.; Gross, M.M.; Heazell, A.E.; Leisher, S.H.; et al. Care in subsequent pregnancies following stillbirth: An international survey of parents. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donegan, G.; Noonan, M.; Bradshaw, C. Parents experiences of pregnancy following perinatal loss: An integrative review. Midwifery 2023, 121, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainali, A.; Infanti, J.J.; Thapa, S.B.; Jacobsen, G.W.; Larose, T.L. Anxiety and depression in pregnant women who have experienced a previous perinatal loss: A case-cohort study from Scandinavia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Jackson, L.; Bezance, I.; Horsch, A. “A renewed sense of purpose”: Mothers’ and fathers’ experience of having a child following a recent stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, T.A.; Roberts, S.A.; Camacho, E.; Heazell, A.E.P.; Massey, R.N.; Melvin, C.; Newport, R.; Smith, D.M.; Storey, C.O.; Taylor, W. Better maternity care pathways in pregnancies after stillbirth or neonatal death: A feasibility study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Standards for Bereavement Care Following Pregnancy Loss and Perinatal Death. Health Service Executive. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/acute-hospitals-division/woman-infants/national-reports-on-womens-health/national-standards-for-bereavement-care-following-pregnancy-loss-and-perinatal-death.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Gaudet, C.; Séjourné, N.; Camborieux, L.; Rogers, R.; Chabrol, H. Pregnancy after perinatal loss: Association of grief, anxiety and attachment. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2010, 28, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heazell, A.E.P.; Barron, R.; Fockler, M.E. Care in pregnancy after stillbirth. Semin. Perinatol. 2024, 48, 151872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorović, A.; O’Higgins, A.; Johnston, S.; Hilton, N.; Webster, G.; Kelly, B. Navigating Psychosocial Aspects of Pregnancy Care After Baby Loss: A Roadmap for Professionals. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaldi, C.; Levi, M.; Angeli, E.; Romeo, G.; Biffino, M.; Bonaiuti, R.; Vannacci, A. Stillbirth and perinatal care: Are professionals trained to address parents’ needs? Midwifery 2018, 64, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.; Shevlin, M.; Elklit, A. Psychological Consequences of Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death in a Sample of Bereaved Parents. J. Loss Trauma 2014, 19, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi, C.; Mosconi, L.; Crescioli, G.; Lombardo, G.; Russo, I.; Morese, A.; Ricca, V.; Vannacci, A. Are midwives trained to recognise perinatal depression symptoms? Results of MAMA (MAternal Mood Assessment) cross-sectional survey in Italy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2024, 27, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260178 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Fondazione Confalonieri Ragonese. Gestione Della Morte Endouterina Fetale (MEF). Prendersi Cura Della Natimortalità. Raccomandazioni 2023. SIGO, AOGOI, AGUI. Available online: https://www.aogoi.it/media/8827/17-raccomandazioni-mef-definitiva-7-febbraio-2023-min.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Ravaldi, C.; Mosconi, L.; Bonaiuti, R.; Vannacci, A. The emotional landscape of pregnancy and postpartum during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: A mixed-method analysis using artificial intelligence. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaldi, C.; Vannacci, A. Small Hands, Big Ideas: Exploring Nurturing Care Through Beatrice Alemagna’s “What is a Child?”. Med Humanit. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heazell, A.E.P.; Siassakos, D.; Blencowe, H.; Burden, C.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Cacciatore, J.; Dang, N.; Das, J.; Flenady, V.; Gold, K.J.; et al. Stillbirths: Economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet 2016, 387, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté-Arsenault, D. The influence of perinatal loss on anxiety in multigravidas. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté-Arsenault, D.; Bidlack, D.; Humm, A. Women’s emotions and concerns during pregnancy following perinatal loss. Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2001, 26, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyirem, S.; Salifu, Y.; Bayuo, J.; Duodu, P.A.; Bossman, L.F.; Abboah-Offei, M. An integrative review of the use of the concept of reassurance in clinical practice. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1515–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamber, K.K.; Barron, R.; Tomlinson, E.; Heazell, A.E. Evaluating patient experience to improve care in a specialist antenatal clinic for pregnancy after loss. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi, C.; Mosconi, L.; Mannetti, L.; Checconi, M.; Bonaiuti, R.; Ricca, V.; Mosca, F.; Dani, C.; Vannacci, A. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and burnout in healthcare professionals working in neonatal intensive care units: Results from the STRONG study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1050236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi, C.; Carelli, E.; Frontini, A.; Mosconi, L.; Tagliavini, S.; Cossu, E.; Crescioli, G.; Lombardi, N.; Bonaiuti, R.; Bettiol, A.; et al. The BLOSSoM study: Burnout after perinatal LOSS in Midwifery. Results of a nation-wide investigation in Italy. Women Birth 2022, 35, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, M.R. Trauma-Informed Maternity Care. In Trauma-Informed Healthcare Approaches; Gerber, M.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology: Empathy. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical Zone | North | 141 | 70.5% |

| Center | 36 | 18.0% | |

| South | 23 | 11.5% | |

| Age Class | <35 y | 80 | 40.0% |

| 36–42 y | 63 | 31.5% | |

| ≥43 y | 57 | 28.5% | |

| Years of Work | <8 y | 74 | 37.0% |

| 9–16 y | 60 | 30.0% | |

| ≥17 y | 66 | 33.0% | |

| Job | Midwife | 156 | 78.0% |

| Doctor | 26 | 13.0% | |

| Nurse | 12 | 6.0% | |

| Psychologist | 6 | 3.0% | |

| 200 | 100.0% |

| N (%)/ Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | 200 (100.0%) | |

| Presence of a center for at-risk pregnancies | ||

| Yes, I refer women there | 165 (88.2%) | |

| Yes, I don’t refer women there | 8 (4.3%) | |

| No | 5 (2.7%) | |

| Don’t know | 9 (4.8%) | |

| Perinatal deaths assisted | ||

| None | 15 (8.0%) | |

| <3 | 33 (17.6%) | |

| 3–5 | 46 (24.6%) | |

| 6–10 | 47 (25.1%) | |

| >10 | 46 (24.6%) | |

| Subsequent pregnancies assisted | ||

| None | 26 (13.9%) | |

| <3 | 49 (26.2%) | |

| 3–5 | 50 (26.7%) | |

| 6–10 | 29 (15.5%) | |

| >10 | 33 (17.6%) | |

| Assisted only labor, not pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 138 (73.8%) | |

| No | 37 (19.8%) | |

| Don’t remember | 12 (6.4%) | |

| Debriefing experience available | ||

| Yes | 57 (30.5%) | |

| No | 122 (65.2%) | |

| Don’t know | 8 (4.3%) | |

| Debriefing experience importance (0–4) | ||

| Available and attended | 3.6 (0.5) | |

| Not available/never attended | 3.6 (0.6) | |

| Specific training on perinatal loss | ||

| Yes | 59 (32.8%) | |

| No | 119 (66.1%) | |

| Don’t remember | 2 (1.1%) | |

| Usefulness of training (0–4) | 3.6 (0.6) | |

| Attended | 3.7 (0.7) | |

| Never attended | 3.6 (0.5) |

| Test/Procedure | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 1st trimester | |

| Vital signs | 95 (81.9%) |

| Urine test | 102 (87.9%) |

| Urine culture | 96 (82.8%) |

| Blood test | 113 (97.4%) |

| Ultrasound | 113 (97.4%) |

| Pap test | 44 (37.9%) |

| Nuchal translucency | 104 (89.7%) |

| Chorionic villus sampling | 19 (16.4%) |

| Amniocentesis | 15 (12.9%) |

| 2nd trimester | |

| Blood test | 112 (96.6%) |

| Vital signs | 109 (94.0%) |

| Fundal height | 97 (83.6%) |

| Glucose test | 82 (70.7%) |

| Ultrasound | 115 (99.1%) |

| 3rd trimester | |

| Blood test | 115 (99.1%) |

| Vital signs | 110 (94.8%) |

| Fundal height | 105 (90.5%) |

| Strep test | 106 (91.4%) |

| Anti-d prophylaxis | 110 (94.8%) |

| Information Provided | I Trimester | II Trimester | III Trimester | Post-Partum | Never |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle counseling | 95 (88.0%) | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.8%) | 6 (5.6%) |

| Psychological wellbeing | 84 (77.8%) | 3 (2.8%) | 4 (3.7%) | 5 (4.6%) | 12 (11.1%) |

| Nurturing care | 26 (24.1%) | 20 (18.5%) | 34 (31.5%) | 20 (18.5%) | 8 (7.4%) |

| Labor | 3 (2.8%) | 29 (26.9%) | 69 (63.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 6 (5.6%) |

| Birth mode | 7 (6.5%) | 35 (32.4%) | 57 (52.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (7.4%) |

| Pain management | 1 (0.9%) | 23 (21.3%) | 72 (66.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | 11 (10.2%) |

| Hospital contacts | 6 (5.6%) | 21 (19.4%) | 73 (67.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 7 (6.5%) |

| Breastfeeding | 1 (0.9%) | 17 (15.7%) | 65 (60.2%) | 13 (12.0%) | 12 (11.1%) |

| Psychological support | 69 (63.9%) | 15 (13.9%) | 11 (10.2%) | 4 (3.7%) | 9 (8.3%) |

| Prenatal classes | 36 (33.3%) | 55 (50.9%) | 6 (5.6%) | 2 (1.9%) | 9 (8.3%) |

| Cephalic presentation | 5 (4.6%) | 33 (30.6%) | 59 (54.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 10 (9.3%) |

| Postpartum services | 16 (14.8%) | 7 (6.5%) | 53 (49.1%) | 20 (18.5%) | 12 (11.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ravaldi, C.; Mosconi, L.; Cancellieri, G.; Caglioni, M.; Vannacci, A. Management of Subsequent Pregnancy After Perinatal Death: Results from the UNSURENESS Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165748

Ravaldi C, Mosconi L, Cancellieri G, Caglioni M, Vannacci A. Management of Subsequent Pregnancy After Perinatal Death: Results from the UNSURENESS Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(16):5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165748

Chicago/Turabian StyleRavaldi, Claudia, Laura Mosconi, Greta Cancellieri, Martina Caglioni, and Alfredo Vannacci. 2025. "Management of Subsequent Pregnancy After Perinatal Death: Results from the UNSURENESS Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 16: 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165748

APA StyleRavaldi, C., Mosconi, L., Cancellieri, G., Caglioni, M., & Vannacci, A. (2025). Management of Subsequent Pregnancy After Perinatal Death: Results from the UNSURENESS Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(16), 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165748