Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Achalasia Following Pneumatic Dilation Treatment: A Single Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Correlation of Preprocedural Patient Characteristics

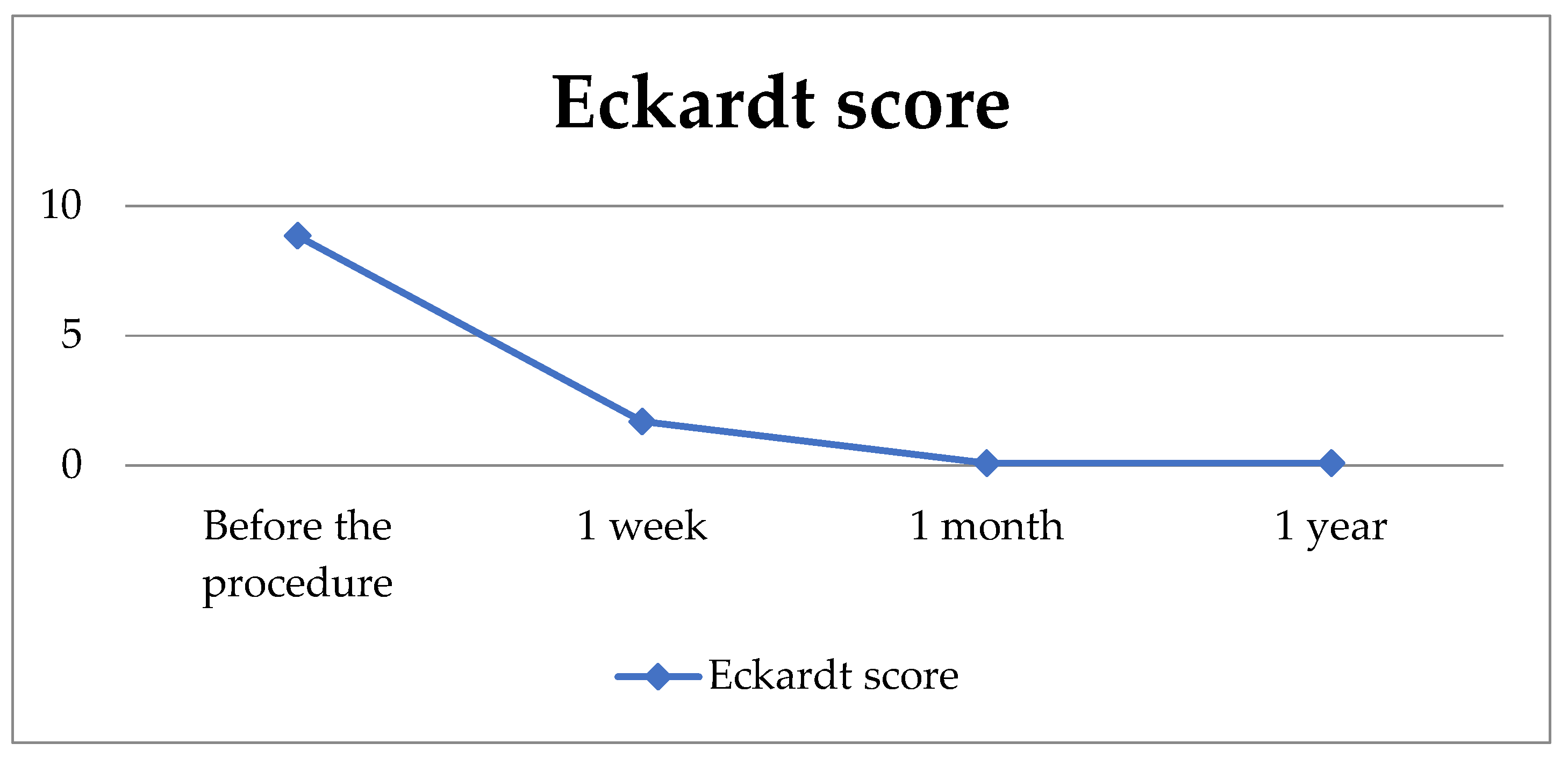

3.3. Postprocedural Outcomes

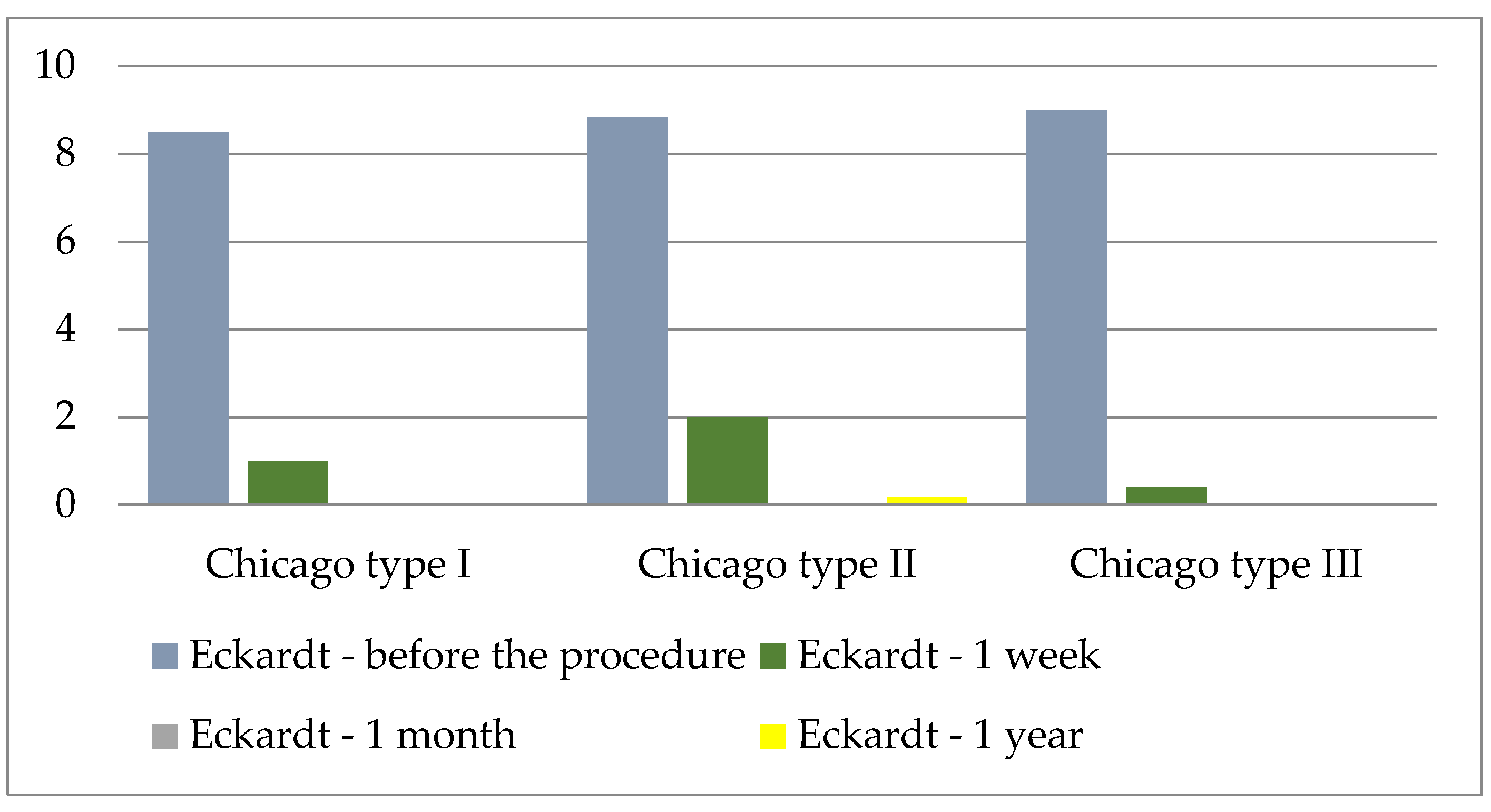

3.4. Procedure Efficiency Regarding the Chicago Classification

3.5. Procedure Efficiency Regarding the Type of Dilator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Pneumatic dilation |

| p | p-value |

| LES | Lower esophageal sphincter |

| EGJ | Esophagogastric junction |

| EGDS | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| POEM | Peroral endoscopic myotomy |

| ESGE | European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

| M | Mean |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Min. | Minimum |

| Max. | Maximum |

| N | Sample size |

| M | Male |

| F | Female |

| y | Year |

| Regurg. | Regurgitation |

| F | F-ratio |

| df | Degrees of freedom |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| t | t-test with Bonferroni correction |

| class. | Classification |

References

- Pandolfino, J.E.; Gawron, A.J. Achalasia: A systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triadafilopoulos, G.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; Gullo, R.; Patti, M.G.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Kahrilas, P.J.; Duranceau, A.; Jamieson, G.; Zaninotto, G. The Kagoshima consensus on esophageal achalasia. Dis. Esophagus 2012, 25, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Buckton, G.K.; Bennett, J.R. Balloon dilation in achalasia: A new dilator. Gut 1986, 27, 986–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandolfino, J.E.; Kwiatek, M.A.; Nealis, T.; Bulsiewicz, W.; Post, J.; Kahrilas, P.J. Achalasia: A new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.M.; Wong, R.K. Review article: The management of achalasia—A comparison of different treatment modalities. Aliment. Pharm. Ther. 2006, 24, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annese, V.; Bassotti, G. Non-surgical treatment of esophageal achalasia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 5763–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.M.; Li, L. Meta-analysis of randomized and controlled treatment trials for achalasia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 2303–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, M.H.; Raisi, M.; Amini, J.; Tabatabai, A.; Haghighi, M.; Tavakoli, H.; Hashemi, M.; Fude, M.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Goharian, V. Pneumatic balloon dilation therapy is as effective as esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Dysphagia 2008, 23, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, F.; Ioannou, A.; Azzaroli, F.; Bazzoli, F. Treatment of achalasia in the era of high-resolution manometry. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hulselmans, M.; Vanuytsel, T.; Degreef, T.; Sifrim, D.; Coosemans, W.; Lerut, T.; Tack, J. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanuytsel, T.; Lerut, T.; Coosemans, W.; Vanbeckevoort, D.; Blondeau, K.; Boeckxstaens, G.; Tack, J. Conservative management of esophageal perforations during pneumatic dilation for idiopathic esophageal achalasia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, H.; Minami, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sato, Y.; Kaga, M.; Suzuki, M.; Satodate, H.; Odaka, N.; Itoh, H.; Kudo, S. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy 2010, 42, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumbhari, V.; Tieu, A.H.; Onimaru, M.; El Zein, M.H.; Teitelbaum, E.N.; Ujiki, M.B.; Gitelis, M.E.; Modayil, R.J.; Hungness, E.S.; Stavropoulos, S.N.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) vs. laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) for the treatment of Type III achalasia in 75 patients: A multicenter comparative study. Endosc. Int. Open 2015, 3, E195–E201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weusten, B.L.A.M.; Barret, M.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Familiari, P.; Gonzalez, J.M.; van Hooft, J.; Ishaq, S.; Lorenzo-Zúñiga, V.; Louis, H.; van Meer, S.; et al. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal motility disorders–Part 1: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2020, 52, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taft, T.H.; Carlson, D.A.; Triggs, J.; Craft, J.; Starkey, K.; Yadlapati, R.; Gregory, D.; Pandolfino, J.E. Evaluating the reliability and construct validity of the Eckardt symptom score as a measure of achalasia severity. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, V.F.; Aignherr, C.; Bernhard, G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ye, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, X.S.; Tang, Y.R.; Jiang, L.Q. Sex differences in symptoms, high-resolution manometry values and efficacy of peroral endoscopic myotomy in Chinese patients with achalasia. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, R.; Manabe, N.; Sakae, H.; Hamada, K.; Ayaki, M.; Murao, T.; Fujita, M.; Kamada, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Haruma, K. Clinical characteristics and manometric findings of esophageal achalasia-a systematic review regarding differences among three subtypes. J. Smooth Muscle Res. 2023, 59, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.A.; Kou, W.; Rooney, K.P.; Baumann, A.J.; Donnan, E.; Triggs, J.R.; Teitelbaum, E.N.; Holmstrom, A.; Hungness, E.; Sethi, S.; et al. Achalasia subtypes can be identified with functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) panometry using a supervised machine learning process. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e13932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljebreen, A.M.; Samarkandi, S.; Al-Harbi, T.; Al-Radhi, H.; Almadi, M.A. Efficacy of pneumatic dilation in Saudi achalasia patients. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanolis, G.; Sgouros, S.; Karatzias, G.; Papadopoulou, E.; Vasiliadis, K.; Stefanidis, G.; Mantides, A. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.A.; Naik, R.; Slaughter, J.C.; Higginbotham, T.; Silver, H.; Vaezi, M.F. Weight loss in achalasia is determined by its phenotype. Dis. Esophagus 2018, 31, doy046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifácio, P.; de Moura, D.T.H.; Bernardo, W.M.; de Moura, E.T.H.; Farias, G.F.A.; Neto, A.C.M.; Lordello, M.; Korkischko, N.; Sallum, R.; de Moura, E.G.H. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy in the treatment of achalasia: Systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 32, doy105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzka, D.A.; Castell, D.O. Review article: An analysis of the efficacy, perforation rates and methods used in pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Alim Pharm. Ther. 2011, 34, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaezi, M.F.; Baker, M.E.; Achkar, E.; Richter, J.E. Timed barium oesophagram: Better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut 2002, 50, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vantrappen, G.; Hellemans, J.; Deloof, W.; Valembois, P.; Vandenbroucke, J. Treatment of achalasia with pneumatic dilations. Gut 1971, 12, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, T. Pneumatic balloon dilation for achalasia—How and why I do it. Ann. Esophagus 2020, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Cuesta, P.; Hervás Molina, A.J.; Jurado García, J.; Pleguezuelo Navarro, M.; García Sánchez, V.; Casáis Juanena, L.L.; Gálvez Calderón, C.; Naranjo Rodríguez, A. Dilatación neumática en el tratamiento de pacientes con acalasia. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 36, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honein, K.; Slim, R.; Yaghi, C.; Kheir, B.; Bou Jaoudé, J.; Sayegh, R. Traitement de l’achalasie par dilation pneumatique: Expérience locale sur une série de 41 cas. J. Méd. Liban. 2007, 55, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoeij, F.B.; Prins, L.I.; Smout, A.J.P.M.; Bredenoord, A.J. Efficacy and safety of pneumatic dilation in achalasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, F.; Thétiot, V.; Richy, F.; Benajah, D.A.; Message, L.; Lamouliatte, H. Repeated pneumatic dilations as long-term maintenance therapy for esophageal achalasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuset, J.A.; Luján, M.; Huguet, J.M.; Canelles, P.; Medina, E. Endoscopic pneumatic balloon dilation in primary achalasia: Predictive factors, complications, and long-term follow-up. Dis. Esophagus 2009, 22, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiu, S.I.; Chang, C.H.; Tu, Y.K.; Ko, C.W. The comparisons of different therapeutic modalities for idiopathic achalasia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e29441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenlik, İ.; Öztürk, Ö.; Özin, Y.; Arı, D.; Coşkun, O.; Turan Gökçe, D.; Kılıç, Z.M.Y. Pneumatic dilation in geriatric achalasia patients. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 34, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, D.; Banerjee, A.; Das, K.; Das, K.; Dhali, G.K. Outcome of sequential dilation in achalasia cardia patients: A prospective cohort study. Esophagus Off. J. Jpn. Esophageal Soc. 2022, 19, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlollahi, N.; Anushiravani, A.; Rahmati, M.; Amani, M.; Asl-Soleimani, H.; Markarian, M.; Jiang, A.C.; Mikaeli, J. Safety and efficacy of graded gradual pneumatic balloon dilation in idiopathic achalasia patients: A 24-year single-center experience. Arch. Iran. Med. 2021, 24, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponds, F.A.; Fockens, P.; Lei, A.; Neuhaus, H.; Beyna, T.; Kandler, J.; Bredenoord, A.J. Effect of peroral endoscopic myotomy vs. pneumatic dilation on symptom severity and treatment outcomes among treatment-naive patients with achalasia: A randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, F.; Cortellini, F.; Azzaroli, F.; Ioannou, A.; Mularoni, C.; Shoshan, D.; Bazzoli, F. Graded pneumatic dilation in subtype I and II achalasia: Long-term experience in a single center. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2022, 35, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borotto, E.; Gaudric, M.; Danel, B.; Samama, J.; Quartier, G.; Chaussade, S.; Couturier, D. Risk factors of oesophageal perforation during pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Gut 1996, 39, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, H.P.; Reynolds, J.C.; Ouyang, A.; Rosato, E.F.; Eisenberg, J.M.; Cohen, S. Pneumatic dilation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: Clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1993, 38, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.L.; Hirsch, D.P.; Bartelsman, J.F.; de Borst, J.; Ferwerda, G.; Tytgat, G.N.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than 5 years. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, T.; Ponds, F.A.; Fockens, P.; Bastiaansen, B.A.J.; Lei, A.; Oude Nijhuis, R.A.B.; Neuhaus, H.; Beyna, T.; Kandler, J.; Frieling, T.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilation in treatment-naive patients with achalasia: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Khan, Z.; Kamal, M.U.; Jirapinyo, P.; Thompson, C.C. Short-term outcomes after peroral endoscopic myotomy, Heller myotomy, and pneumatic dilation in patients with achalasia: A nationwide analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 97, 871–879.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptom | Severity | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (kg) | ||

| none | 0 | |

| <5 kg | 1 | |

| 5–10 kg | 2 | |

| >10 kg | 3 | |

| Dysphagia | ||

| none | 0 | |

| occasional | 1 | |

| every day | 2 | |

| during each meal | 3 | |

| Retrosternal pain | ||

| none | 0 | |

| occasional | 1 | |

| every day | 2 | |

| during each meal | 3 | |

| Regurgitation | ||

| none | 0 | |

| occasional | 1 | |

| every day | 2 | |

| during each meal | 3 |

| Variable | N (%) | M | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | 6 (26.1) | ||||

| F | 17 (73.9) | |||||

| Dysphagia | 23 (100) | |||||

| Regurgitation | 23 (100) | |||||

| Retrosternal pain | 23 (100) | |||||

| Weight loss | 23 (100) | |||||

| Age (years) | 61.48 | 11.40 | 39 | 83 | ||

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 22.48 | 20.53 | 2 | 75 | ||

| Variable | Gender | Age (y) | Symptom Duration * | Dysphagia | Retrosternal Pain | Pain Duration ** | Painful Episodes *** | Regurg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||||

| Age (y) | 0.168 | 1 | ||||||

| Symptom Duration * | 0.059 | −0.199 | 1 | |||||

| Dysphagia | 0.455 | 0.025 | −0.007 | 1 | ||||

| Retrostenal Pain | −0.059 | 0.394 | 0.010 | −0.039 | 1 | |||

| Pain Duration ** | 0.000 | 0.110 | −0.115 | 0.137 | 0.167 | 1 | ||

| Painful Episodes *** | 0.034 | −0.023 | 0.351 | −0.098 | 0.006 | −0.589 | 1 | |

| Regurg. | −0.194 | −0.473 | 0.444 | 0.190 | −0.011 | −0.127 | 0.081 | 1 |

| Eckardt Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Initial | 1 Week | 4 Weeks | 1 Year | F | df | p * |

| Dysphagia | 2.22 ± 0.74 | 0.83 ± 1.23 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 48.9 | 3/22 | <0.001 |

| Retrosternal pain | 1.91 ± 0.90 | 0.39 ± 0.66 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 62.6 | 3/22 | <0.001 |

| Regurgitation | 1.91 ± 0.79 | 0.35 ± 0.49 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | 69.8 | 3/22 | <0.001 |

| Symptom | Time-Frame | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysphagia | ||||

| Before the procedure | 1 week | 4.64 | 22 | <0.001 |

| 1 month | 14.45 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 year | 14.45 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 week | 1 month | 3.22 | 22 | 0.024 |

| 1 year | 3.22 | 22 | 0.024 | |

| 1 month | 1 year | 0.00 | 22 | 1.000 |

| Regurgitation | ||||

| Before the procedure | 1 week | 7.24 | 22 | <0.001 |

| 1 month | 10.50 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 year | 10.50 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 week | 1 month | 2.79 | 22 | 0.065 |

| 1 year | 2.31 | 22 | 0.183 | |

| 1 month | 1 year | 0.00 | 22 | 1.000 |

| Retrosternal pain | ||||

| Before the procedure | 1 week | 6.75 | 22 | <0.001 |

| 1 month | 10.19 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 year | 10.19 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| 1 week | 1 month | 2.86 | 22 | 0.055 |

| 1 year | 2.86 | 22 | 0.055 | |

| 1 month | 1 year | 0.00 | 22 | 1.000 |

| Body Weight | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 week | 1 month | −6.54 | 2 | <0.001 |

| 1 year | −6.63 | 2 | <0.001 | |

| 1 month | 1 year | −2.98 | 2 | 0.021 |

| F | df | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time measurement point | 106.97 | 3/10 | <0.001 |

| Chicago class. | 1.06 | 2/10 | 0.382 |

| Time measurement point × Chicago class. | 0.535 | 6/30 | 0.777 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabljić, V.; Božić, D.; Aličić, D.; Ardalić, Ž.; Olić, I.; Bonacin, D.; Žaja, I. Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Achalasia Following Pneumatic Dilation Treatment: A Single Center Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155448

Sabljić V, Božić D, Aličić D, Ardalić Ž, Olić I, Bonacin D, Žaja I. Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Achalasia Following Pneumatic Dilation Treatment: A Single Center Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155448

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabljić, Viktorija, Dorotea Božić, Damir Aličić, Žarko Ardalić, Ivna Olić, Damir Bonacin, and Ivan Žaja. 2025. "Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Achalasia Following Pneumatic Dilation Treatment: A Single Center Experience" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155448

APA StyleSabljić, V., Božić, D., Aličić, D., Ardalić, Ž., Olić, I., Bonacin, D., & Žaja, I. (2025). Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Achalasia Following Pneumatic Dilation Treatment: A Single Center Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155448