Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Nasal Skin Cancer Reconstruction: Enhancing Esthetic Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty

2.3. Subjective Outcomes

2.4. Imaging Methodology

2.5. Subjective Peer Assessment by Oncodermatology Specialists

3. Results

- Population

- 2.

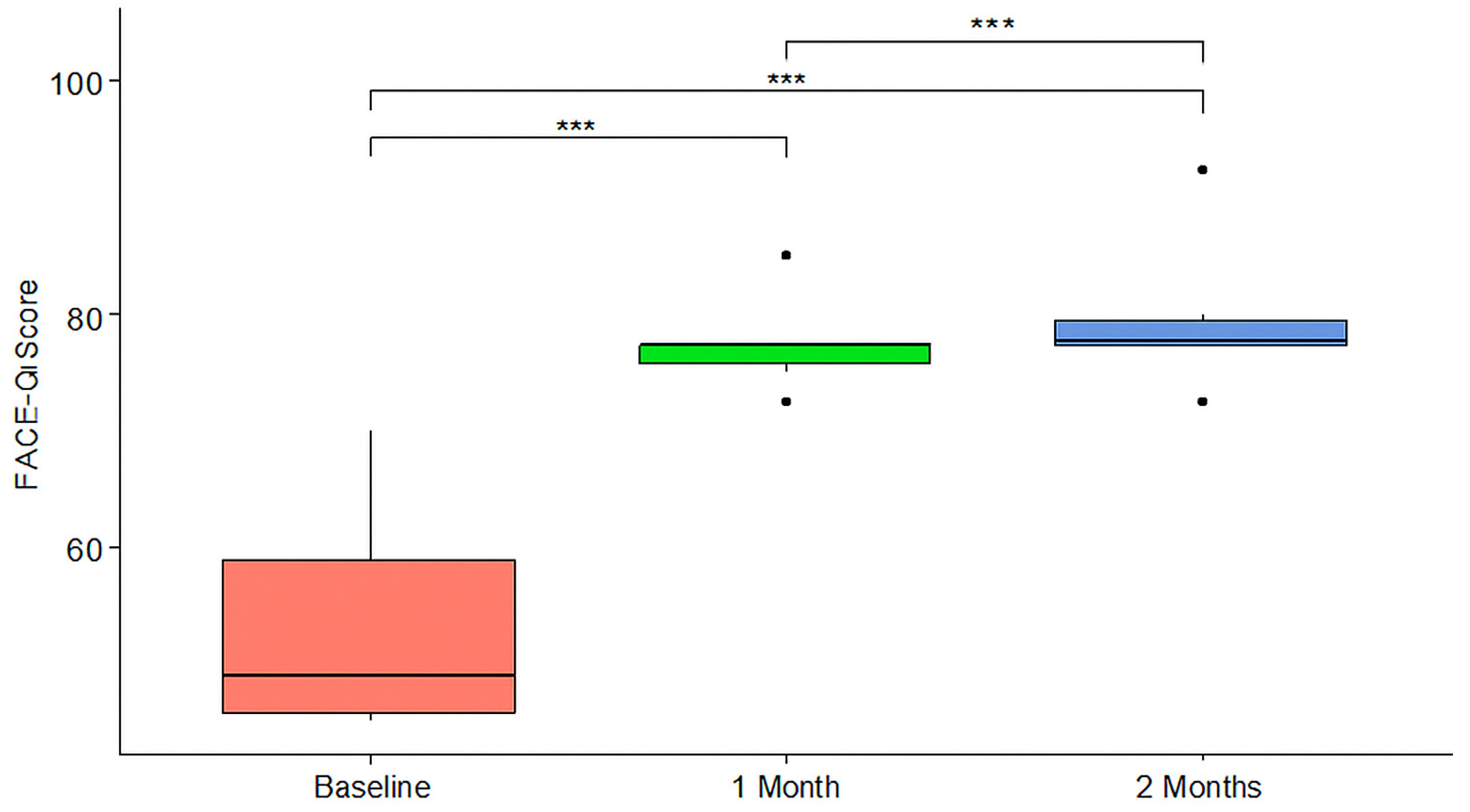

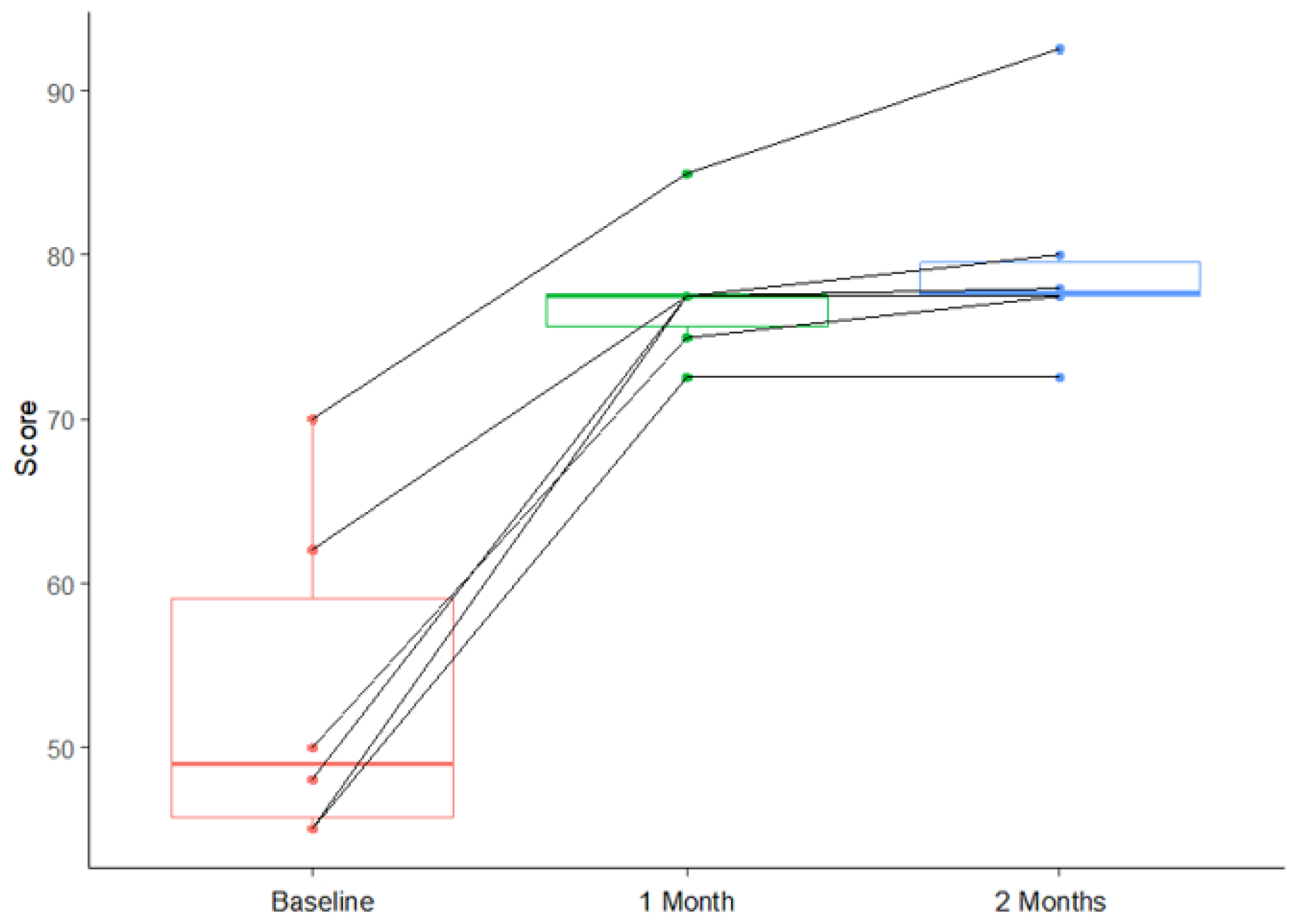

- FACE-Q outcomes

- 3.

- Specialist evaluation and volumetric outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christopoulos, G.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Karantonis, F.; Karypidis, D.; Hampsas, G.; Kostopoulos, E.; Kostaki, M.; Papadopoulos, O. Surgical Treatment and Recurrence of Cutaneous Nasal Malignancies: A 26-Year Retrospective Review of 1795 Patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, e2–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panje, W.R.; Ceilley, R.I. Nasal skin cancer: Hazard to a uniquely exposed structure. Postgrad. Med. 1979, 66, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fijałkowska, M.; Koziej, M.; Antoszewski, B. Detailed head localization and incidence of skin cancers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, N.N.; McGuire, J.F.; Dyson, S.; Chark, D. Nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck II: Surgical treatment and reconstruction. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2009, 30, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, A.; Grekin, R.; Neuhaus, I.; Saylor, D.; Yu, S.; Park, A.; Seth, R.; Knott, P.D. Long-Term Appearance-Related Outcomes of Facial Reconstruction After Skin Cancer Resection. Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2023, 25, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.W. Quality of Life Studies in Skin Cancer Treatment and Reconstruction. Facial Plast. Surg. 2020, 36, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montero, P.; De Gálvez-Aranda, M.V.; Blázquez-Sánchez, N.; Rivas-Ruíz, F.; Millán-Cayetano, J.F.; García-Harana, C.; De Troya Martín, M. Quality of Life During Treatment for Cervicofacial Non-melanoma Skin Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răducu, L.; Avino, A.; Purnichescu Purtan, R.; Balcangiu-Stroescu, A.-E.; Bălan, D.G.; Timofte, D.; Ionescu, D.; Jecan, C.-R. Quality of Life in Patients with Surgically Removed Skin Tumors. Medicina 2020, 56, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulesco, T.; De Bonnecaze, G.; Penicaud, M.; Dessi, P.; Michel, J. Patient Satisfaction After Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty Using Hyaluronic Acid: A Literature Review. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2896–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.isaps.org/media/lcvdjt1f/isaps-global-survey_2024.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- De Stefani, A.; Barone, M.; Hatami Alamdari, S.; Barjami, A.; Baciliero, U.; Apolloni, F.; Gracco, A.; Bruno, G. Validation of Vectra 3D Imaging Systems: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.D.; Mazzaferro, D.; Habarth-Morales, T.E.; Messa, C.A.; Talwar, A.A.; Desai, A.A.; McAuliffe, P.B.; Broach, R.B.; Serletti, J.M.; Percec, I. A Large Prospective Volumetric and Patient-Reported Outcome Analysis of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers to the Face. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulesco, T.; Braccini, F.; Kestemont, P.; Winter, C.; Castillo, L.; Michel, J. A Safe Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty Procedure. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 83e–86e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulesco, T.; Penicaud, M.; Santini, L.; Graziani, J.; Dessi, P.; Michel, J. French validation of the FACE-Q Rhinoplasty module. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2019, 44, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoldelli, C.; Benat, G.; Castillo, L.; Chamorey, E.; Lutz, J.-C. Accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility of a handheld three-dimensional facial imaging device: The Vectra H1. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, K.R. Nasal reconstruction using 20 mg/ml cross-linked hyaluronic acid. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2006, 5, 465–466. [Google Scholar]

- Nyte, C.P. Hyaluronic acid Spreader-Graft Injection for Internal Nasal Valve Collapse. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007, 86, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Gadea, A.; Sevil-Serrano, C.; Buendía Pérez, J.; Mariño-Sánchez, F. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Rhinoplasty: A Systematic Review of the Technique, Results, and Complications. Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2025, 27, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, A. Medical rhinoplasty with hyaluronic acid and botulinum toxin A: A very simple and quite effective technique. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2008, 7, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie, D.S.; AlEdani, E.M.; Gurramkonda, J.; Chaudhri, S.; Amin, A.; Panjiyar, B.K.; Nath, T.S. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty (NSR): A Systematic Review of Its Techniques, Outcomes, and Patient Satisfaction. Cureus 2023, 15, e50728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaye, D.A. The history of nasal reconstruction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 29, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menick, F.J. Nasal Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 138e–150e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovacchini, F.; Monarchi, G.; Mitro, V.; Gilli, M.; Tullio, A. Nasal Reconstruction in 4-years-old Child Affected by Nasal wing Cleft. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 2438–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Griffin, J.R.; Ansari, M.; Beran, S.J.; Potter, J.K. Nasal Reconstruction—Beyond Aesthetic Subunits: A 15-Year Review of 1334 Cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 114, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, T.S.; Mori, S.; Dusza, S.W.; Rossi, A.M.; Nehal, K.S.; Lee, E.H. Appearance-related psychosocial distress following facial skin cancer surgery using the FACE-Q Skin Cancer. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenhof, M.J.; Veldhuizen, I.J.; Hensbergen, L.J.V.; Blankensteijn, L.L.; Bramer, W.; Lei, B.V.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Hulst, R.R.W.J.; Sidey-Gibbons, C.J. The Use of the FACE-Q Aesthetic: A Narrative Review. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 2769–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, G.A.G.; Melita, D.; Stivala, A.; Cuomo, R.; Tamburino, S. Assessing the Long-Term Impact of Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty on Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life: A Prospective Study Using FACE-Q. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demesh, D.; Cristel, R.T.; Gandhi, N.D.; Kola, E.; Issa, T.Z.; Dayan, S.H. Effects of hyaluronic acid filler injection for non-surgical rhinoplasty on first impressions and quality of life (FACE-Q scale). J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3351–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.; Nicolai, E.S.J.; He, J.J.; Roshchupkin, G.V.; Corten, E.M.L. 3D surface imaging technology for objective automated assessment of facial interventions: A systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 4264–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneduce, N.; Botter, C.; Coiante, E.; Hersant, B.; Meningaud, J.-P. The longevity of the nonsurgical rhinoplasty: A literature review. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.N.A.; Roswandi, N.L.; Waqas, M.; Habib, H.; Hussain, F.; Khan, S.; Sohail, M.; Ramli, N.A.; Thu, H.E.; Hussain, Z. Hyaluronic acid, a promising skin rejuvenating biomedicine: A review of recent updates and pre-clinical and clinical investigations on cosmetic and nutricosmetic effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, A.; Firooz, A.; Samadi, A. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of booster injections of hyaluronic acid in improving the facial skin quality. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 2267–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghatge, A.S.; Ghatge, S.B. The Effectiveness of Injectable Hyaluronic Acid in the Improvement of the Facial Skin Quality: A Systematic Review. CCID 2023, 16, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, L.C.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Klaassen, C.D.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel; Andersen, F.A. Final Report of the Safety Assessment of Hyaluronic Acid, Potassium Hyaluronate, and Sodium Hyaluronate. Int. J. Toxicol. 2009, 28, 5–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Peng, K.; Sarode, A.; Prakash, S.; Zhao, Z.; Filippov, S.K.; Todorova, K.; Sell, B.R.; Lujano, O.; Bakre, S.; et al. Hyaluronic acid conjugates for topical treatment of skin cancer lesions. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Li, Q. Restylane Lyft for Aesthetic Shaping of the Nasal Dorsum and Radix: A Randomized, No-Treatment Control, Multicenter Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-V.T.; Sykes, K.; Kriet, J.D.; Humphrey, C. Cartilage Graft Donor Site Morbidity following Rhinoplasty and Nasal Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofac Trauma. Reconstr. 2018, 11, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P. Rhinofiller: Fat Grafting (Surgical) Versus Hyaluronic Acid (Non-Surgical). Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Bae, J.; Youn, K.; Kim, W.; Suwanchinda, A.; Tanvaa, T.; Kim, H. Topography of the dorsal nasal artery and its clinical implications for augmentation of the dorsum of the nose. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Won, S.; O, J.; Hu, K.; Mun, S.; Yang, H.; Kim, H. The facial artery: A Comprehensive Anatomical Review. Clin. Anat. 2018, 31, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelke, L.W.; Fick, M.; van Rijn, L.J.; Decates, T.; Velthuis, P.J.; Niessen, F. [Unilateral blindness following a non-surgical rhinoplasty with filler]. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2017, 161, D1246. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z. Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty: An Updated Systematic Review of Technique, Outcomes, Complications, and Its Treatments. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 4902–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassir, R.; Venkataram, A.; Malek, A.; Rao, D. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty: The Ascending Technique and a 14-Year Retrospective Study of 2130 Cases. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.H.; Seo, K.K. Filler Rhinoplasty Evaluated by Anthropometric Analysis. Dermatol. Surg. 2016, 42, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, A.; Brewster, C.T. The Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty: A Retrospective Review of 5000 Treatments. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, M.; Gazzola, R.; Metalla, M.; Vaienti, L. The Role of Hyaluronidase in the Treatment of Complications from Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2013, 33, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouanet, C.; Kestemont, P.; Winter, C.; Lerhe, B.; Savoldelli, C. Management of vascular complications following facial hyaluronic acid injection: High-dose hyaluronidase protocol: A technical note. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Cao, H.; He, X.; Zou, X.; Mao, H.; Tang, L.; Lu, J. Skin necrosis after autologous fat grafting for augmentation rhinoplasty: A case report and review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2024, 26, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Mosahebi, A.; Zargaran, D. A Scoping Review of Hyaluronidase Use in Managing the Complications of Aesthetic Interventions. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, R.M.; Sandkvist, U.; Lundgren, B. Degradation of Hylauronic Acid Fillers Using Hyaluronidase in an In Vivo Model. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2018, 17, 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, M.L.W.; Levin, M.K.; Marmur, E.S. The Kinetics of Reversible Hyaluronic Acid Filler Injection Treated with Hyaluronidase. Dermatol. Surg. 2017, 43, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.H.; Gehrman, M.D.; Graham, J.H. Botulinum Toxin A and B Improve Perfusion, Increase Flap Survival, Cause Vasodilation, and Prevent Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Animal Studies. Hand 2023, 18, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelken, J.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-S.; Chang, C.-J.; Yang, J.-Y.; Chuang, S.-S.; Chen, H.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-C. Donor Site Aesthetic Enhancement with Preoperative Botulinum Toxin in Forehead Flap Nasal Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ren, L. Botulinum Toxin Type A Inhibits Connective Tissue Growth Factor Expression in Fibroblasts Derived from Hypertrophic Scar. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2011, 35, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhibo, X.; Miaobo, Z. Botulinum toxin type A affects cell cycle distribution of fibroblasts derived from hypertrophic scar. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2008, 61, 1128–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziade, G.; Saade, R.; Daou, D.; Karam, D.; Bendito, A.; Tsintsadze, M. Nasal Reshaping Using Barbed Threads Combined with Hyaluronic Acid Filler and Botulinum Toxin A. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (years) | Histological Type T-Stage and Margin Status | Number of Surgeries | Time Since Last Oncologic Surgery (Months) | Time Since Last Cosmetic Surgery (Months) | Reconstruction | Injection Target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 77 | SCC; T2; R0 | 1 | 30 | 30 | Rintala flap | Saddle nose correction |

| Patient 2 | 64 | BCC; T1; R0 | 3 | 23 | 3 | Skin graft | Graft expansion |

| Patient 3 | 62 | SCC; T3; R0 | 7 | 48 | 10 | Bilateral frontal flap | Nasal tip projection |

| Patient 4 | 37 | Melanoma; T2; R0 | 4 | 100 | 93 | Cartilage graft and local flaps | Saddle nose correction |

| Patient 5 | 68 | SCC; T3; R0 | 10 | 43 | 6 | Frontal and nasolabial flaps | Dorsum symetrisation |

| Patient 6 | 42 | BCC; T2; R0 | 2 | 12 | 12 | Double nasolabial flaps | Dorsum projection |

| FACE-Q Score | Baseline (n = 6) | 1 Month (n = 6) | 2 Months (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) | 53.33 (±10.31) | 77.50 (±4.18) | 79.67 (±6.76) |

| Median [IQR] | 49.00 [45.75–59.00] | 77.50 [75.62–77.50] | 77.75 [77.50–79.50] |

| Minimum | 45.00 | 72.50 | 72.50 |

| Maximum | 70.00 | 85.00 | 92.50 |

| Compared Consultations. | Mean Differences with 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline vs. 1 Month | 24.17 (16.47; 31.86) | <0.001 |

| Baseline vs. 2 Months | 26.33 (19.51; 33.16) | <0.001 |

| 1 Month vs. 2 Months | 2.17 (−0.83; 5.17) | 0.122 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahan Shoushtari, S.; Savoldelli, C.; Gobillot, H.; Castillo, L.; Poissonnet, G.; Kestemont, P.; D’Andréa, G.; Vandersteen, C. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Nasal Skin Cancer Reconstruction: Enhancing Esthetic Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155394

Tahan Shoushtari S, Savoldelli C, Gobillot H, Castillo L, Poissonnet G, Kestemont P, D’Andréa G, Vandersteen C. Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Nasal Skin Cancer Reconstruction: Enhancing Esthetic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155394

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahan Shoushtari, Shahin, Charles Savoldelli, Héloïse Gobillot, Laurent Castillo, Gilles Poissonnet, Philippe Kestemont, Grégoire D’Andréa, and Clair Vandersteen. 2025. "Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Nasal Skin Cancer Reconstruction: Enhancing Esthetic Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155394

APA StyleTahan Shoushtari, S., Savoldelli, C., Gobillot, H., Castillo, L., Poissonnet, G., Kestemont, P., D’Andréa, G., & Vandersteen, C. (2025). Non-Surgical Rhinoplasty After Nasal Skin Cancer Reconstruction: Enhancing Esthetic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155394