Postoperative Morbidity Is Not Associated with a Worse Mid-Term Quality of Life After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

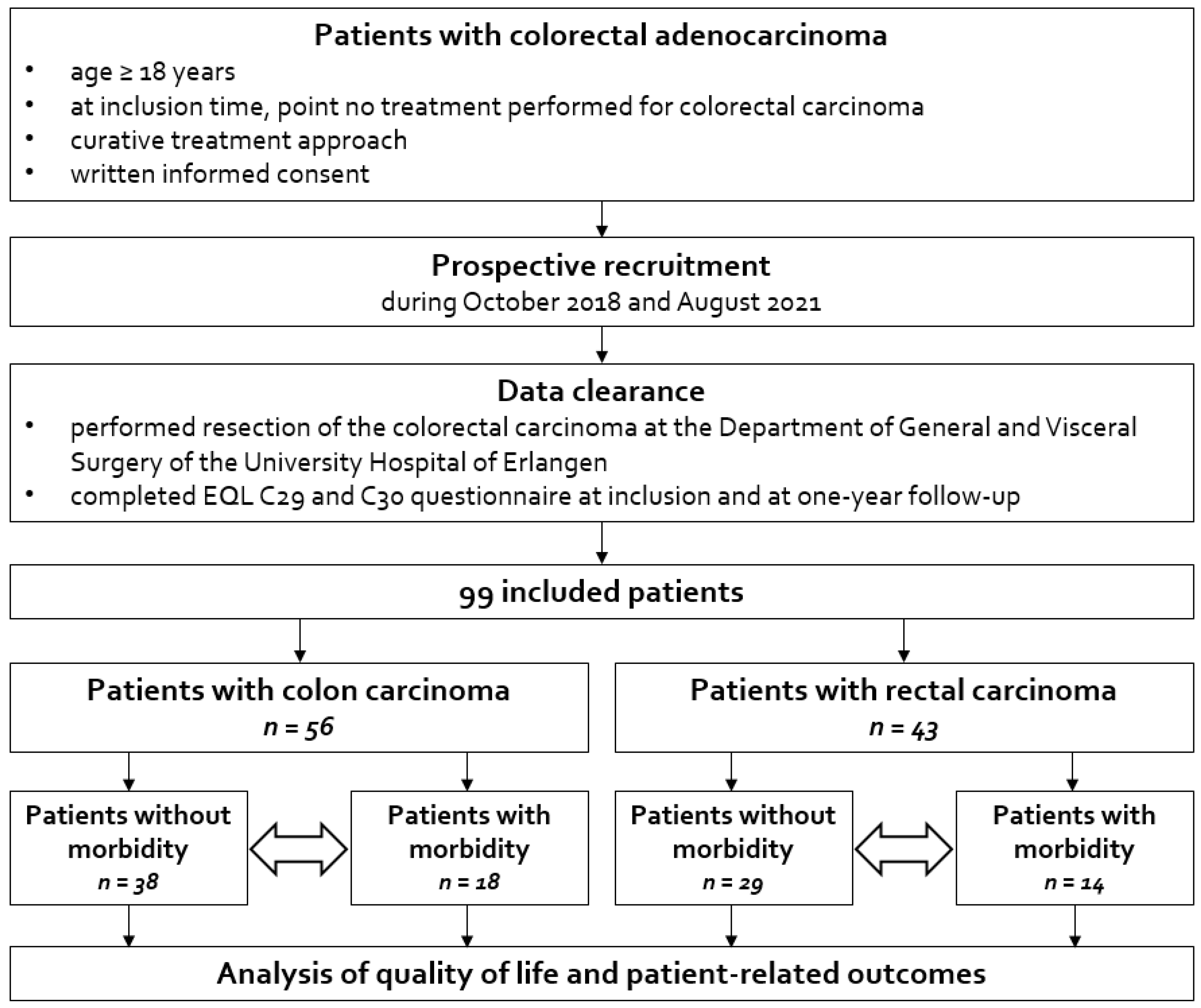

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Therapeutic Algorithm of Patients with Colorectal Carcinomas

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Collective

3.2. Outcome Parameter After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Malignancy

3.2.1. Colonic Carcinoma Group

3.2.2. Rectal Carcinoma Group

3.3. Quality of Life and Patient-Related Outcomes in the Entire Cohort

3.3.1. Colonic Carcinoma Patients

3.3.2. Rectal Carcinoma Patients

3.4. Quality of Life and Patient-Related Outcomes Stratified to Postoperative Morbidity

3.4.1. Colonic Carcinoma Patients

3.4.2. Rectal Carcinoma Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, C.; Yoshino, T.; Ruíz-García, E.; Mostafa, N.; Cann, C.G.; O'Brian, B.; Benny, A.; Perez, R.O.; Cremolini, C. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2024, 404, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Kolorektales Karzinom, Langversion 2.1, 2019, AWMF Registrierungsnummer: 021/007OL. Available online: http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/kolorektales-karzinom/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Andersson, J.; Angenete, E.; Gellerstedt, M.; Angerås, U.; Jess, P.; Rosenberg, J.; Fürst, A.; Bonjer, J.; Haglind, E. Health-related quality of life after laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer in a randomized trial. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 941–949, Erratum in Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 1746. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arndt, V.; Merx, H.; Stegmaier, C.; Ziegler, H.; Brenner, H. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4829–4836, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walming, S.; Asplund, D.; Bock, D.; Gonzalez, E.; Rosenberg, J.; Smedh, K.; Angenete, E. Quality of life in patients with resectable rectal cancer during the first 24 months following diagnosis. Color. Dis. 2020, 22, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kowalski, C.; Sibert, N.T.; Breidenbach, C.; Hagemeier, A.; Roth, R.; Seufferlein, T.; Benz, S.; Post, S.; Siegel, R.; Wiegering, A.; et al. Outcome Quality After Colorectal Cancer Resection in Certified Colorectal Cancer Centers—Patient-Reported and Short-Term Clinical Outcomes. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2022, 119, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sjövall, A.; Lagergren, P.; Johar, A.; Buchli, C. Quality of life and patient reported symptoms after colorectal cancer in a Swedish population. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, J.; Kerr, J.; Schlesinger-Raab, A.; Eckel, R.; Sauer, H.; Hölzel, D. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients: A four-year prospective study. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varpe, P.; Huhtinen, H.; Rantala, A.; Salminen, P.; Rautava, P.; Hurme, S.; Grönroos, J. Quality of life after surgery for rectal cancer with special reference to pelvic floor dysfunction. Color. Dis. 2011, 13, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, L.; Bock, D.; Asplund, D.; Ohlsson, B.; Rosenberg, J.; Angenete, E. Urinary dysfunction in patients with rectal cancer: A prospective cohort study. Color. Dis. 2020, 22, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sörensson, M.; Asplund, D.; Matthiessen, P.; Rosenberg, J.; Hallgren, T.; Rosander, C.; González, E.; Bock, D.; Angenete, E. Self-reported sexual dysfunction in patients with rectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2020, 22, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vonk-Klaassen, S.M.; de Vocht, H.M.; den Ouden, M.E.; Eddes, E.H.; Schuurmans, M.J. Ostomy-related problems and their impact on quality of life of colorectal cancer ostomates: A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siddiqi, A.; Given, C.W.; Given, B.; Sikorskii, A. Quality of life among patients with primary, metastatic and recurrent cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2009, 18, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algie, J.P.A.; van Kooten, R.T.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Peeters, K.C.M.J.; Dekker, J.W.T. Stoma versus anastomosis after sphincter-sparing rectal cancer resection; the impact on health-related quality of life. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 2197–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pachler, J.; Wille-Jørgensen, P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 12, CD004323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gessler, B.; Eriksson, O.; Angenete, E. Diagnosis, treatment, and consequences of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montroni, I.; Ugolini, G.; Saur, N.M.; Rostoft, S.; Spinelli, A.; Van Leeuwen, B.L.; De Liguori Carino, N.; Ghignone, F.; Jaklitsch, M.T.; Kenig, J.; et al. SIOG Surgical Task Force/ESSO GOSAFE Study Group. Predicting Functional Recovery and Quality of Life in Older Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery: Real-World Data from the International GOSAFE Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5247–5262, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2111–2112. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.24.00763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosma, E.; Pullens, M.J.; de Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A. The impact of complications on quality of life following colorectal surgery: A prospective cohort study to evaluate the Clavien-Dindo classification system. Color. Dis. 2016, 18, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosma, E.; Pullens, M.J.; de Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A. Health status, anxiety, and depressive symptoms following complicated and uncomplicated colorectal surgeries. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2016, 31, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orive, M.; Anton-Ladislao, A.; Lázaro, S.; Gonzalez, N.; Bare, M.; Fernandez de Larrea, N.; Redondo, M.; Bilbao, A.; Sarasqueta, C.; Aguirre, U.; et al. Anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life, and mortality among colorectal patients: 5-year follow-up. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7943–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UICC (International Union of Cancer). TNM Classifcation of Malignant Tumours, 8th ed.; Brierley, J.D., Gospodarowicz, M.K., Wittekind, C., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baum, P.; Diers, J.; Lichthardt, S.; Kastner, C.; Schlegel, N.; Germer, C.T.; Wiegering, A. Mortality and Complications Following Visceral Surgery: A Nationwide Analysis Based on the Diagnostic Categories Used in German Hospital Invoicing Data. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brunner, M.; ElGendy, A.; Denz, A.; Weber, G.; Grützmann, R.; Krautz, C. Roboterassistierte viszeralchirurgische Eingriffe in Deutschland: Eine Analyse zum aktuellen Stand sowie zu Trends der letzten 5 Jahre anhand von StuDoQ|Robotik-Registerdaten [Robot-assisted visceral surgery in Germany: Analysis of the current status and trends of the last 5 years using data from the StuDoQ|Robotics registry]. Chirurgie 2023, 94, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wee, I.J.Y.; Seow-En, I.; Chok, A.Y.; Sim, E.; Koo, C.H.; Lin, W.; Meihuan, C.; Tan, E.K. Postoperative outcomes after prehabilitation for colorectal cancer patients undergoing surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Ann. Coloproctol. 2024, 40, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neudecker, J.; Klein, F.; Bittner, R.; Carus, T.; Stroux, A.; Schwenk, W.; LAPKON II Trialists. Short-term outcomes from a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 1458–1467, Erratum in: Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C.; Haviland, J.; Winter, J.; Grimmett, C.; Chivers Seymour, K.; Batehup, L.; Calman, L.; Corner, J.; Din, A.; Fenlon, D.; et al. Members of the Study Advisory Committee. Pre-Surgery Depression and Confidence to Manage Problems Predict Recovery Trajectories of Health and Wellbeing in the First Two Years following Colorectal Cancer: Results from the CREW Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al Rashid, F.; Liberman, A.S.; Charlebois, P.; Stein, B.; Feldman, L.S.; Fiore, J.F., Jr.; Lee, L. The impact of bowel dysfunction on health-related quality of life after rectal cancer surgery: A systematic review. Tech. Coloproctol. 2022, 26, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunoda, A.; Nakao, K.; Hiratsuka, K.; Yasuda, N.; Shibusawa, M.; Kusano, M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 10, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Basave, H.N.; Morales-Vázquez, F.; Miranda-Dévora, G.; Olmos-García, J.P.; Hernández-Castañeda, K.F.; Rivera-Mogollan, L.G.; Muñoz-Montaño, W.R. Clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer patients under 30 years of age. Cir. Cir. 2023, 91, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, J. Comparison of clinical efficacy of different colon anastomosis methods in laparoscopic radical resection of colorectal cancer. Cir. Cir. 2024, 92, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, M.; Zu'bi, A.; Weber, K.; Denz, A.; Langheinrich, M.; Kersting, S.; Weber, G.F.; Grützmann, R.; Krautz, C. The use of single-stapling techniques reduces anastomotic complications in minimal-invasive rectal surgery. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reudink, M.; Molenaar, C.J.L.; Bonhof, C.S.; Janssen, L.; Mols, F.; Slooter, G.D. Evaluating the longitudinal effect of colorectal surgery on health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 125, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Georges, C.; Yap, R.; Bell, S.; Farmer, K.C.; Cohen, L.C.L.; Wilkins, S.; Centauri, S.; Engel, R.; Oliva, K.; McMurrick, P.J. Comparison of quality of life, symptom and functional outcomes following surgical treatment for colorectal neoplasia. ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Characteristics | Colon Carcinoma | Rectal Carcinoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Without Morbidity (n = 38) | Patients with Morbidity (n = 18) | p | Patients Without Morbidity (n = 29) | Patients with Morbidity (n = 14) | p | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 72 (12) | 72 (9) | 0.766 | 62 (11) | 70 (10) | 0.110 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.563 | 0.744 | ||||

| Female | 17 (45) | 6 (33) | 10 (35) | 4 (29) | ||

| Male | 21 (55) | 12 (67) | 19 (65) | 10 (71) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28.1 (6.3) | 28.6 (5.1) | 0.307 | 28.0 (9.8) | 26.1 (7.3) | 0.568 |

| ASA classification, n (%) | 0.744 | 0.640 | ||||

| I | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (14) | 1 (7) | ||

| II | 24 (63) | 11 (61) | 17 (59) | 7 (50) | ||

| III | 10 (26) | 7 (39) | 8 (28) | 6 (43) | ||

| IV | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Neoadjuvant treatment, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 0.099 | 15 (52) | 7 (50) | 1.000 |

| Surgical procedure | 0.523 | 0.029 | ||||

| Right hemicolectomy | 26 (68) | 13 (72) | ||||

| Left hemicolectomy | 8 (21) | 2 (11) | ||||

| Sigmoid resection | 3 (8) | 1 (6) | ||||

| Colectomy | 1 (3) | 2 (11) | ||||

| Rectal resection | - | - | 29 (100) | 11 (79) | ||

| Rectal extirpation | - | - | 0 (0) | 3 (21) | ||

| Adjuvant treatment, n (%) | 8 (21) | 7 (39) | 0.202 | 3 (10) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| (y)pT, n (%) | 1.000 | 0.758 | ||||

| 0/1/2 | 12 (32) | 5 (28) | 14 (48) | 6 (43) | ||

| 3/4 | 26 (68) | 13 (72) | 15 (52) | 8 (57) | ||

| (y)pN, n (%) | 0.524 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0 | 29 (76) | 12 (67) | 24 (83) | 12 (86) | ||

| 1/2 | 9 (24) | 6 (33) | 5 (17) | 2 (14) | ||

| Complication Characteristics | Patients with Surgery for Colonic Malignancy (n = 56) | Patients with Surgery for Rectal Malignancy (n = 43) |

|---|---|---|

| Morbidity, n (%) | 18 (32) | 14 (33) |

| Clavien–Dindo, n (%) | ||

| I | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| II | 10 (18) | 8 (19) |

| III | 6 (11) | 5 (12) |

| IV | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| V | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 3 (5) | 3 (7) |

| Hematoma, n (%) | 2 (4) | 3 (7) |

| Anastomostic leakage, n (%) | 2 (4) | 3 (7) |

| Re-surgery, n (%) | 5 (9) | 5 (12) |

| QoL Parameter | Patients with Surgery for Colonic Malignancy (n = 56) | Patients with Surgery for Rectal Malignancy (n = 43) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | |

| Functioning scales | ||||||

| Global health status/QoL, mean (SD) | 63 (27) | 72 (22) | 0.012 | 70 (16) | 67 (20) | 0.263 |

| Physical function, mean (SD) | 80 (21) | 79 (24) | 0.748 | 89 (17) | 83 (17) | <0.001 |

| Role function, mean (SD) | 73 (35) | 78 (29) | 0.430 | 81 (27) | 68 (33) | 0.009 |

| Emotional function, mean (SD) | 63 (28) | 76 (24) | 0.009 | 62 (23) | 67 (28) | 0.518 |

| Cognitive function, mean (SD) | 86 (23) | 78 (26) | 0.163 | 90 (18) | 84 (20) | 0.112 |

| Social function, mean (SD) | 76 (31) | 74 (29) | 0.792 | 74 (25) | 67 (32) | 0.081 |

| Symptom scales | ||||||

| Dyspnoea, mean (SD) | 20 (30) | 20 (27) | 0.863 | 14 (23) | 19 (24) | 0.361 |

| Pain, mean (SD) | 21 (26) | 15 (27) | 0.170 | 10 (18) | 25 (31) | 0.003 |

| Fatigue, mean (SD) | 38 (31) | 35 (27) | 0.387 | 26 (22) | 34 (25) | 0.002 |

| Sleep disturbance, mean (SD) | 32 (35) | 29 (37) | 0.589 | 28 (30) | 31 (33) | 0.624 |

| Appetite loss, mean (SD) | 18 (33) | 9 (21) | 0.006 | 13 (24) | 8 (23) | 0.469 |

| Nausea and vomiting, mean (SD) | 4 (14) | 5 (16) | 1.000 | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 1.000 |

| Constipation, mean (SD) | 16 (26) | 5 (16) | 0.003 | 8 (19) | 16 (27) | 0.094 |

| Diarrhoea, mean (SD) | 19 (32) | 26 (26) | 0.482 | 26 (30) | 28 (28) | 0.703 |

| Financial impact, mean (SD) | 7 (16) | 7 (19) | 0.687 | 8 (18) | 21 (36) | 0.020 |

| Anxiety, mean (SD) | 37 (35) | 64 (31) | <0.001 | 36 (30) | 47 (36) | 0.013 |

| Weight, mean (SD) | 76 (35) | 71 (29) | 0.773 | 81 (22) | 76 (23) | 0.057 |

| Body image, mean (SD) | 83 (21) | 82 (24) | 0.986 | 86 (18) | 74 (26) | 0.005 |

| Sexual interests (only men), mean (SD) | 45 (27) | 40 (35) | 1.000 | 43 (30) | 57 (27) | 0.619 |

| Sexual interests (only women), mean (SD) | 24 (32) | 24 (33) | 0.563 | 24 (32) | 33 (32) | 1.000 |

| High urinary frequency, mean (SD) | 44 (30) | 35 (21) | 0.019 | 36 (26) | 37 (23) | 0.307 |

| Urinary incontinence, mean (SD) | 10 (20) | 12 (22) | 0.827 | 4 (13) | 2 (8) | 1.000 |

| Dysuria, mean (SD) | 3 (15) | 0 (0) | 0.500 | 5 (14) | 4 (12) | 1.000 |

| Abdominal pain, mean (SD) | 22 (26) | 10 (19) | 0.002 | 11 (17) | 13 (17) | 1.000 |

| Buttock pain, mean (SD) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 0.766 | 10 (22) | 30 (33) | <0.001 |

| Bloated feeling, mean (SD) | 22 (31) | 17 (24) | 0.491 | 16 (21) | 26 (26) | 0.263 |

| Blood and mucus in stool, mean (SD) | 9 (18) | 1 (6) | 0.003 | 31 (32) | 5 (11) | <0.001 |

| Dry mouth, mean (SD) | 23 (34) | 22 (28) | 0.974 | 15 (20) | 21 (25) | 0.728 |

| Hair loss, mean (SD) | 4 (14) | 16 (28) | 0.027 | 2 (11) | 7 (22) | 1.000 |

| Trouble with taste, mean (SD) | 8 (21) | 15 (28) | 0.315 | 6 (16) | 13 (27) | 0.031 |

| Flatulence, mean (SD) | 24 (26) | 37 (26) | 0.227 | 20 (23) | 43 (31) | 0.002 |

| Faecal incontinence/leakage, mean (SD) | 7 (15) | 11 (24) | 0.437 | 6 (19) | 28 (32) | 0.002 |

| Sore skin around anus/stoma, mean (SD) | 11 (18) | 17 (26) | 0.108 | 8 (18) | 40 (38) | <0.001 |

| Stool frequency/bag change, mean (SD) | 13 (21) | 20 (26) | 0.180 | 31 (29) | 44 (30) | 0.014 |

| Embarrassed by defaecation pattern/stoma, mean (SD) | 3 (10) | 8 (19) | 0.148 | 7 (20) | 31 (36) | <0.001 |

| Impotence (only men), mean (SD) | 46 (41) | 61 (38) | 0.563 | 37 (34) | 47 (37) | 0.021 |

| Dyspareunia (only women), mean (SD) | 5 (17) | 8 (19) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 12 (31) | 0.500 |

| QoL Parameter | Patients Without Postoperative Complications (n = 38) | Patients with Postoperative Complications (n = 18) | Comparison of Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-up | |

| Functioning scales | ||||||||

| Global health status/QoL, mean (SD) | 65 (27) | 70 (23) | 0.486 | 59 (26) | 77 (18) | 0.004 | 0.426 | 0.288 |

| Physical function, mean (SD) | 80 (22) | 81 (23) | 0.789 | 79 (19) | 76 (28) | 0.406 | 0.760 | 0.608 |

| Role function, mean (SD) | 73 (35) | 77 (30) | 0.955 | 72 (34) | 79 (28) | 0.250 | 0.768 | 0.857 |

| Emotional function, mean (SD) | 63 (29) | 73 (24) | 0.108 | 63 (26) | 82 (21) | 0.031 | 0.858 | 0.289 |

| Cognitive function, mean (SD) | 87 (23) | 78 (29) | 0.019 | 84 (23) | 77 (19) | 0.828 | 0.671 | 0.470 |

| Social function, mean (SD) | 73 (33) | 73 (30) | 0.770 | 82 (25) | 79 (26) | 1.000 | 0.380 | 0.670 |

| Symptom scales | ||||||||

| Dyspnoea, mean (SD) | 18 (27) | 20 (27) | 0.415 | 24 (36) | 21 (31) | 0.250 | 0.749 | 0.925 |

| Pain, mean (SD) | 23 (26) | 15 (25) | 0.054 | 17 (25) | 17 (34) | 1.000 | 0.360 | 0.699 |

| Fatigue, mean (SD) | 36 (31) | 34 (28) | 0.893 | 41 (31) | 37 (27) | 0.125 | 0.547 | 0.591 |

| Sleep disturbance, mean (SD) | 28 (33) | 31 (38) | 0.640 | 41 (39) | 23 (35) | 0.125 | 0.267 | 0.624 |

| Appetite loss, mean (SD) | 18 (31) | 8 (21) | 0.031 | 22 (36) | 12 (22) | 0.188 | 0.833 | 0.561 |

| Nausea and vomiting, mean (SD) | 4 (13) | 6 (19) | 0.500 | 5 (16) | 2 (5) | 0.750 | 0.762 | 0.576 |

| Constipation, mean (SD) | 15 (26) | 4 (11) | 0.125 | 19 (26) | 6 (13) | 0.031 | 0.649 | 1.000 |

| Diarrhoea, mean (SD) | 17 (33) | 23 (23) | 0.200 | 22 (30) | 33 (33) | 0.563 | 0.304 | 0.435 |

| Financial impact, mean (SD) | 9 (19) | 10 (21) | 0.539 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 0.205 | 0.179 |

| Anxiety, mean (SD) | 36 (33) | 66 (32) | <0.001 | 39 (40) | 61 (29) | 0.008 | 0.933 | 0.563 |

| Weight, mean (SD) | 78 (34) | 72 (26) | 0.614 | 72 (37) | 67 (38) | 0.875 | 0.508 | 0.907 |

| Body image, mean (SD) | 82 (23) | 82 (25) | 0.890 | 85 (16) | 81 (20) | 0.781 | 0.910 | 0.618 |

| Sexual interests (only men), mean (SD) | 52 (27) | 52 (35) | 0.833 | 33 (25) | 39 (39) | 1.000 | 0.064 | 0.442 |

| Sexual interests (only women), mean (SD) | 24 (32) | 26 (35) | 0.375 | 22 (34) | 11 (19) | 1.000 | 0.882 | 0.691 |

| High urinary frequency, mean (SD) | 39 (26) | 33 (21) | 0.139 | 53 (37) | 42 (23) | 0.047 | 0.126 | 0.332 |

| Urinary incontinence, mean (SD) | 7 (18) | 15 (24) | 0.273 | 15 (23) | 3 (10) | 0.312 | 0.202 | 0.189 |

| Dysuria, mean (SD) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.500 | 6 (24) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 0.695 | 1.000 |

| Abdominal pain, mean (SD) | 22 (25) | 9 (17) | 0.033 | 24 (30) | 12 (22) | 0.094 | 0.877 | 0.846 |

| Buttock pain, mean (SD) | 4 (10) | 6 (16) | 0.750 | 4 (11) | 6 (13) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Bloated feeling, mean (SD) | 20 (30) | 15 (24) | 0.625 | 28 (33) | 23 (27) | 0.719 | 0.310 | 0.335 |

| Blood and mucus in stool, mean (SD) | 8 (16) | 1 (3) | 0.008 | 10 (21) | 3 (10) | 0.188 | 0.953 | 0.805 |

| Dry mouth, mean (SD) | 18 (30) | 20 (28) | 0.375 | 33 (40) | 27 (29) | 0.281 | 0.196 | 0.403 |

| Hair loss, mean (SD) | 4 (13) | 13 (25) | 0.047 | 6 (17) | 24 (37) | 0.500 | 0.897 | 0.315 |

| Trouble with taste, mean (SD) | 8 (23) | 13 (29) | 0.438 | 9 (19) | 21 (27) | 0.625 | 0.618 | 0.218 |

| Flatulence, mean (SD) | 25 (26) | 32 (22) | 0.895 | 22 (28) | 52 (31) | 0.063 | 0.589 | 0.071 |

| Faecal incontinence/leakage, mean (SD) | 8 (17) | 10 (23) | 0.883 | 6 (13) | 15 (27) | 0.500 | 0.761 | 0.514 |

| Sore skin around anus/stoma, mean (SD) | 11 (18) | 16 (23) | 0.157 | 9 (19) | 21 (34) | 0.531 | 0.558 | 0.816 |

| Stool frequency/bag change, mean (SD) | 11 (18) | 21 (28) | 0.171 | 15 (27) | 18 (20) | 0.781 | 0.890 | 0.978 |

| Embarrassed by defaecation pattern/stoma, mean (SD) | 2 (8) | 5 (12) | 0.375 | 6 (13) | 15 (31) | 0.500 | 0.317 | 0.478 |

| Impotence (only men), mean (SD) | 46 (40) | 60 (35) | 0.250 | 47 (44) | 61 (49) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.852 |

| Dyspareunia (only women), mean (SD) | 7 (19) | 8 (20) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 11 (19) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| QoL Parameter | Patients Without Postoperative Complications (n = 29) | Patients with Postoperative Complications (n = 14) | Comparison of Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | p | Pre-Treatment | One-Year Follow-Up | |

| Functioning scales | ||||||||

| Global health status/QoL, mean (SD) | 73 (18) | 69 (22) | 0.208 | 64 (10) | 63 (15) | 1.000 | 0.031 | 0.213 |

| Physical function, mean (SD) | 93 (10) | 85 (16) | 0.001 | 80 (25) | 78 (20) | 0.148 | 0.054 | 0.332 |

| Role function, mean (SD) | 87 (24) | 71 (31) | 0.009 | 68 (30) | 58 (38) | 0.375 | 0.010 | 0.392 |

| Emotional function, mean (SD) | 66 (19) | 70 (28) | 0.709 | 55 (30) | 58 (27) | 0.750 | 0.179 | 0.218 |

| Cognitive function, mean (SD) | 90 (19) | 84 (23) | 0.146 | 89 (18) | 83 (13) | 0.875 | 0.711 | 0.561 |

| Social function, mean (SD) | 79 (22) | 71 (31) | 0.191 | 65 (29) | 54 (33) | 0.240 | 0.146 | 0.126 |

| Symptom scales | ||||||||

| Dyspnoea, mean (SD) | 12 (18) | 20 (24) | 0.332 | 19 (31) | 17 (25) | 1.000 | 0.622 | 0.892 |

| Pain, mean (SD) | 8 (15) | 19 (26) | 0.066 | 15 (22) | 42 (37) | 0.063 | 0.224 | 0.086 |

| Fatigue, mean (SD) | 19 (16) | 31 (23) | 0.006 | 39 (27) | 42 (28) | 0.250 | 0.020 | 0.368 |

| Sleep disturbance, mean (SD) | 20 (26) | 26 (29) | 0.756 | 43 (33) | 46 (40) | 1.000 | 0.027 | 0.210 |

| Appetite loss, mean (SD) | 7 (17) | 5 (16) | 0.750 | 24 (33) | 17 (36) | 0.750 | 0.070 | 0.432 |

| Nausea and vomiting, mean (SD) | 2 (7) | 2 (5) | 1.000 | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Constipation, mean (SD) | 8 (19) | 11 (22) | 0.375 | 10 (20) | 29 (38) | 0.125 | 0.947 | 0.119 |

| Diarrhoea, mean (SD) | 26 (30) | 30 (27) | 0.578 | 24 (30) | 21 (31) | 1.000 | 0.759 | 0.336 |

| Financial impact, mean (SD) | 8 (17) | 17 (30) | 0.125 | 7 (19) | 33 (47) | 0.250 | 0.723 | 0.419 |

| Anxiety, mean (SD) | 37 (27) | 53 (34) | 0.004 | 36 (36) | 29 (38) | 1.000 | 0.710 | 0.112 |

| Weight, mean (SD) | 82 (21) | 80 (22) | 0.398 | 81 (25) | 63 (21) | 0.125 | 1.000 | 0.067 |

| Body image, mean (SD) | 88 (17) | 79 (20) | 0.044 | 83 (19) | 60 (34) | 0.078 | 0.451 | 0.153 |

| Sexual interests (only men), mean (SD) | 52 (26) | 57 (20) | 0.922 | 26 (32) | 56 (40) | 0.250 | 0.060 | 1.000 |

| Sexual interests (only women), mean (SD) | 27 (33) | 30 (31) | 1.000 | 17 (33) | 44 (38) | 1.000 | 0.868 | 0.773 |

| High urinary frequency, mean (SD) | 32 (26) | 34 (24) | 0.624 | 44 (26) | 44 (20) | 0.500 | 0.153 | 0.297 |

| Urinary incontinence, mean (SD) | 2 (9) | 2 (7) | 1.000 | 7 (19) | 4 (12) | 1.000 | 0.436 | 1.000 |

| Dysuria, mean (SD) | 2 (9) | 2 (7) | 1.000 | 10 (20) | 12 (17) | 0.500 | 0.248 | 0.048 |

| Abdominal pain, mean (SD) | 11 (18) | 12 (16) | 1.000 | 10 (16) | 17 (18) | 1.000 | 0.916 | 0.678 |

| Buttock pain, mean (SD) | 7 (16) | 29 (35) | 0.004 | 17 (31) | 33 (31) | 0.125 | 0.291 | 0.649 |

| Bloated feeling, mean (SD) | 15 (21) | 23 (26) | 0.425 | 17 (22) | 33 (25) | 0.625 | 0.893 | 0.264 |

| Blood and mucus in stool, mean (SD) | 33 (32) | 5 (12) | 0.003 | 27 (32) | 4 (8) | 0.063 | 0.623 | 1.000 |

| Dry mouth, mean (SD) | 13 (21) | 21 (24) | 0.848 | 19 (17) | 21 (31) | 0.625 | 0.181 | 0.833 |

| Hair loss, mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 5 (21) | 1.000 | 7 (19) | 13 (25) | 1.000 | 0.106 | 0.166 |

| Trouble with taste, mean (SD) | 5 (15) | 12 (24) | 0.125 | 7 (19) | 17 (36) | 0.500 | 0.895 | 1.000 |

| Flatulence, mean (SD) | 23 (25) | 43 (32) | 0.027 | 14 (17) | 42 (30) | 0.094 | 0.348 | 1.000 |

| Faecal incontinence/leakage, mean (SD) | 9 (22) | 30 (35) | 0.016 | 0 (0) | 21 (25) | 0.125 | 0.158 | 0.666 |

| Sore skin around anus/stoma, mean (SD) | 6 (16) | 41 (36) | <0.001 | 12 (21) | 38 (45) | 0.188 | 0.369 | 0.693 |

| Stool frequency/bag change, mean (SD) | 32 (31) | 44 (29) | 0.114 | 27 (25) | 46 (34) | 0.031 | 0.870 | 0.877 |

| Embarrassed by defaecation pattern/stoma, mean (SD) | 7 (21) | 24 (34) | 0.028 | 7 (19) | 50 (36) | 0.016 | 0.858 | 0.048 |

| Impotence (only men), mean (SD) | 33 (30) | 36 (31) | 0.109 | 44 (41) | 72 (39) | 0.250 | 0.569 | 0.027 |

| Dyspareunia (only women), mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 17 (36) | 0.500 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.782 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brunner, M.; Jendrusch, T.; Golcher, H.; Weber, K.; Denz, A.; Weber, G.F.; Grützmann, R.; Krautz, C. Postoperative Morbidity Is Not Associated with a Worse Mid-Term Quality of Life After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145167

Brunner M, Jendrusch T, Golcher H, Weber K, Denz A, Weber GF, Grützmann R, Krautz C. Postoperative Morbidity Is Not Associated with a Worse Mid-Term Quality of Life After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(14):5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145167

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrunner, Maximilian, Theresa Jendrusch, Henriette Golcher, Klaus Weber, Axel Denz, Georg F. Weber, Robert Grützmann, and Christian Krautz. 2025. "Postoperative Morbidity Is Not Associated with a Worse Mid-Term Quality of Life After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Carcinoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 14: 5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145167

APA StyleBrunner, M., Jendrusch, T., Golcher, H., Weber, K., Denz, A., Weber, G. F., Grützmann, R., & Krautz, C. (2025). Postoperative Morbidity Is Not Associated with a Worse Mid-Term Quality of Life After Colorectal Surgery for Colorectal Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(14), 5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145167