Assessing Quality of Life Among Women with Urinary Incontinence—Medical, Psychological, and Sociodemographic Determinants

Abstract

1. Introduction

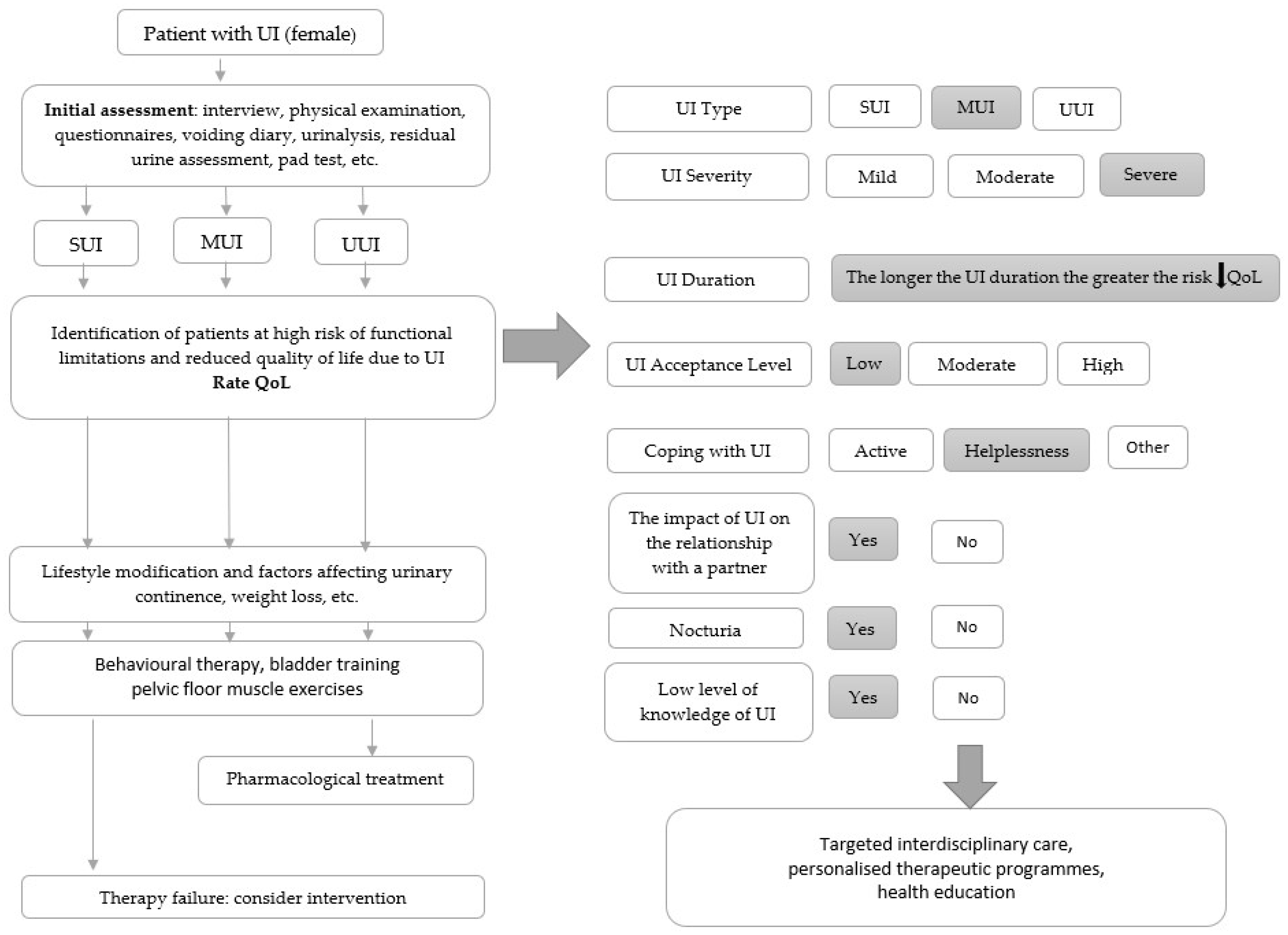

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Research Tools

- Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID). This questionnaire is recommended for differentiating types of incontinence. It consists of six questions about the circumstances of incontinence and urgency to urinate. The first three questions qualify Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI), and the other three qualify Urge Urinary Incontinence (UUI). Responses are summed additively, with scores ranging from 0 to 15 points. Optimal cutoff values of (questions 1, 2, 3) ≥ 4 points and (questions 4, 5, 6) ≥ 6 points identify women with SUI and UUI, respectively. Women are classified as having Mixed Urinary Incontinence (MUI) if both scores are above the optimal cutoff values [2,3].

- Revised Urinary Incontinence Scale (RUIS). This scale is designed to assess the severity of urinary incontinence. It consists of five questions, and each answer is scored accordingly. The score ranges from 0 to 16 points: 0–3 = no UI or very mild, 4–8 = mild severity of symptoms, 9–12 = moderate, and 13–16 = a severe form of UI [4].

- Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS). This scale provides information about the patient’s level of acceptance of the disease. It consists of eight statements that address the limitations and difficulties associated with the disease. The score ranges from 8 to 40 points. The higher the score, the better the adaptation and the lower the discomfort from the disease [5].

- Inventory for Measuring Coping with Stress Mini-COPE: This questionnaire provides insight into typical ways of responding in difficult and stressful situations. The survey adopts a seven-factor scale structure, consisting of the following strategies: active coping, helplessness, support-seeking, avoidant behavior, turning to religion, acceptance, and humor [6].

- King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ). This questionnaire is a recommended tool designed to assess the quality of life of women with urinary incontinence. It consists of 21 items that relate to different spheres of life: Part One: general health perception (KHQ1) and incontinence impact (KHQ2); Part Two: role limitations (KHQ3), physical limitations (KHQ4), social limitations (KHQ5), personal relationships (KHQ6), emotions (KHQ7), sleep/energy (KHQ8), and severity measures (KHQ9); Part Three: a scale containing ten different symptoms related to lower urinary tract dysfunction and the degree to which they bother the patient (KHQ10). Responses in Section 1 and Section 2 are scored from 0 (best quality of life) to 100 (worst quality of life). On the other hand, Section 3, when summed up, is scored from 0 (best quality of life) to 30 points (worst quality of life). The lower the score, the better the quality of life in each area of the KHQ. This study used quality-of-life scores in the nine functional areas of the KHQ1-KHQ9. Part three of the questionnaire provided information on the nature of the complaints necessary for medical verification [7].

- Set of Scales for Self-Assessment of the relationship with a partner. This includes three five-item scales: the Emotional Bond Self-Assessment Scale, the Sexual Bond Self-Assessment Scale, and the Relationship Self-Assessment Scale. One has to choose the response that most closely corresponds to their relationship in a given area [8].

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Group

3.2. Type of UI vs. Assessment of Quality of Life

3.3. UI Severity and Quality-of-Life Assessment

3.4. UI Duration and Quality of Life

3.5. Level of Acceptance of Disease and Quality of Life

3.6. Strategies to Deal with Stress and Quality of Life

3.7. Satisfaction with a Relationship with a Partner and Quality of Life

3.8. Sociodemographic Factors and Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciepiela, K.; Dzięcielska, M.; Kwaśniewska, P.; Michalczuk, K.; Michałek, T.; Szewczyk, M. Patient with UI in the Healthcare System 2024 (Pacjent z NTM w systemie opieki zdrowotnej 2024); Association of People with Urinary Incontinence (UroConti): Warsaw, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://uroconti.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Pacjent-z-NTM-w-systemie-opieki-zdrowotnej-2024.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025). (In Polish)

- Bradley, C.S.; Rahn, D.D.; Nygaard, I.E.; Barber, M.D.; Nager, C.W.; Kenton, K.S.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Abel, R.B.; Spino, C.; Richter, H.E. The Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID): Validity and Responsiveness to Change in Women Undergoing Non-Surgical Therapies for Treatment of Stress Predominant Urinary Incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, S.A.; Bent, A.; Amir-Khalkhali, B.; Rittenberg, D.; Zilbert, A.; Farrell, K.D.; O’Connell, C.; Fanning, C. Women’s Ability to Assess Their Urinary Incontinence Type Using the QUID as an Educational Tool. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansoni, J.E.; Hawthorne, G.E.; Marosszeky, N.; Fleming, G. The Revised Urinary Incontinence Scale: A Clinical Validation. Aust. N. Z. Cont. J. 2015, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z. Measurement Tools in Health Promotion and Psychology, 2nd ed.; Psychological Testing Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; ISBN 978-83-60733-43-1. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. Tools for Measuring Stress and Coping with Stress; Psychological Testing Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; ISBN 978-83-60733-47-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar, S.; Pandey, H.; Chawla, A. Understanding King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ) in Assessment of Female Urinary Incontinence. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzan, M. Quality of Life of Patients with Varying Degrees of Stress Urinary Incontinence; Impuls Publishing: Krakow, Poland, 2008; ISBN 978-83-7587-001-5. [Google Scholar]

- Asoglu, M.R.; Selcuk, S.; Cam, C.; Cogendez, E.; Karateke, A. Effects of Urinary Incontinence Subtypes on Women’s Quality of Life (Including Sexual Life) and Psychosocial State. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 176, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboia, D.M.; Firmiano, M.L.V.; Bezerra, K.d.C.; Vasconcelos, J.A.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M. Impact of urinary incontinence types on women’s quality of life. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, A.C.; Huang, A.J.; Van den Eeden, S.K.; Knight, S.K.; Creasman, J.M.; Yang, J.; Ragins, A.I.; Thom, D.H.; Brown, J.S. Mixed Urinary Incontinence: Greater Impact on Quality of Life. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedicação, A.C.; Haddad, M.; Saldanha, M.E.S.; Driusso, P. Comparison of Quality of Life for Different Types of Female Urinary Incontinence. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Chung, M.-H.; Liao, C.-H.; Su, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-K.; Liao, Y.-M. Urinary Incontinence and Sleep Quality in Older Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 15642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.Y.; Wiseman, J.B.; Cella, D.; Bradley, C.S.; Lai, H.H.; Helmuth, M.E.; Smith, A.R.; Griffith, J.W.; Amundsen, C.L.; Kenton, K.S.; et al. Mental Health, Sleep and Physical Function in Treatment Seeking Women with Urinary Incontinence. J. Urol. 2018, 200, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barentsen, J.A.; Visser, E.; Hofstetter, H.; Maris, A.M.; Dekker, J.H.; de Bock, G.H. Severity, Not Type, Is the Main Predictor of Decreased Quality of Life in Elderly Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Population-Based Study as Part of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Primary Care. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monz, B.; Chartier-Kastler, E.; Hampel, C.; Samsioe, G.; Hunskaar, S.; Espuna-Pons, M.; Wagg, A.; Quail, D.; Castro, R.; Chinn, C. Patient Characteristics Associated with Quality of Life in European Women Seeking Treatment for Urinary Incontinence: Results from PURE. Eur. Urol. 2007, 51, 1073–1081; discussion 1081–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.-J.; Kwon, B. Predictive Risk Factors for Impaired Quality of Life in Middle-Aged Women with Urinary Incontinence. Int. Neurourol. J. 2010, 14, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krhut, J.; Gärtner, M.; Mokris, J.; Horcicka, L.; Svabik, K.; Zachoval, R.; Martan, A.; Zvara, P. Effect of Severity of Urinary Incontinence on Quality of Life in Women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 1925–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paick, J.-S.; Cho, M.C.; Oh, S.-J.; Kim, S.W.; Ku, J.H. Influence of Self-Perceived Incontinence Severity on Quality of Life and Sexual Function in Women with Urinary Incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2007, 26, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoja, I.; Degmečić, D. Quality of Life and Female Sexual Dysfunction in Croatian Women with Stress-, Urgency- and Mixed Urinary Incontinence: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2019, 55, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Giardulli, B.; Polito, F.; Aprea, S.; Lanzano, M.; Dodaro, C. The Impact of Urinary Incontinence on Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Metropolitan City of Naples. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, J.; Lurbiecki, J. Acceptance of illness scale and its clinical impact. Pol. Merkur. Lek. Organ Pol. Tow. Lek. 2014, 36, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Senra, C.; Pereira, M.G. Quality of Life in Women with Urinary Incontinence. Rev. Assoc. Medica Bras. 1992 2015, 61, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksenbaum, L.M.; Greenglass, E.R.; Eaton, J. Perceived Social Support, Hassles, and Coping Among the Elderly. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2006, 25, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, N.; Qu, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, K. Relationships among Symptom Severity, Coping Styles, and Quality of Life in Community-Dwelling Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Multiple Mediator Model. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2016, 25, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanmardifard, S.; Gheibizadeh, M.; Shirazi, F.; Zarea, K.; Ghodsbin, F. Experiences of Urinary Incontinence Management in Older Women: A Qualitative Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 738202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczuk, J.; Szymona-Pałkowska, K.; Robak, J.M.; Rykowska-Górnik, K.; Steuden, S.; Kraczkowski, J.J. Coping with Stress and Quality of Life in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Menopause Rev. Menopauzalny 2015, 14, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović Segedi, L.; Segedi, D.; Parezanović Ilić, K. Quality of Life in Women with Urinary Incontinence. Med. Glas. 2011, 8, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi Fakari, F.; Hajian, S.; Darvish, S.; Alavi Majd, H. Explaining Factors Affecting Help-Seeking Behaviors in Women with Urinary Incontinence: A Qualitative Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Jackson, C.; Nelson, A.; Iles-Smith, H.; McGowan, L. Exploring Support, Experiences and Needs of Older Women and Health Professionals to Inform a Self-Management Package for Urinary Incontinence: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, H.C.; Serody, L.; Patrick, S.; Maurer, J.; Bensasi, S.; Houck, P.R.; Mazumdar, S.; Nofzinger, E.A.; Bell, B.; Nebes, R.D.; et al. Sleeping Well, Aging Well: A Descriptive and Cross-Sectional Study of Sleep in “Successful Agers” 75 and Older. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz Bulut, T.; Altay, B. Sleep Quality and Quality of Life in Older Women With Urinary Incontinence Residing in Turkey: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2020, 47, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G.; Larson, D.B.; Larson, S.S. Religion and Coping with Serious Medical Illness. Ann. Pharmacother. 2001, 35, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 2012, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, T.F.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. The Physiology of Marriage: Pathways to Health. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 79, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehulić, J.; Kamenov, Ž. Mental Health in Affectionate, Antagonistic, and Ambivalent Relationships During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Profile Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 631615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, E.S.; Erekson, E.A.; Minkin, M.J.; Foran-Tuller, K.A. Sexual Satisfaction in the Elderly Female Population: A Special Focus on Women with Gynecologic Pathology. Maturitas 2011, 70, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, R.L. Female Urinary Incontinence and Sexuality. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temml, C.; Haidinger, G.; Schmidbauer, J.; Schatzl, G.; Madersbacher, S. Urinary Incontinence in Both Sexes: Prevalence Rates and Impact on Quality of Life and Sexual Life. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2000, 19, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delarmelindo, R.d.C.A.; Parada, C.M.G.D.L.; Rodrigues, R.A.P.; Bocchi, S.C.M. Women’s strategies for coping with urinary incontinence. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2013, 47, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.-K.; Chan, A.; Pang, S.; Leung, P.; Tang, C.; Shek, D.; Chung, T. The Impact of Urodynamic Stress Incontinence and Detrusor Overactivity on Marital Relationship and Sexual Function. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Arnedt, J.T.; Pillai, V.; Ciesla, J.A. The Impact of Sleep on Female Sexual Response and Behavior: A Pilot Study. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsahri, P.; Salehnejad, Z.; Hekmat, K.; Abedi, P.; Fakhri, A.; Haghighizadeh, M. Do Sleeping Disorders Impair Sexual Function in Married Iranian Women of Reproductive Age? Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. Psychiatry J. 2018, 2018, 1045738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, L. Analysis of Coping Styles of Elderly Women Patients with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 3, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintos-Díaz, M.Z.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Paz-Zulueta, M.; Fradejas-Sastre, V.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Living with Urinary Incontinence: Potential Risks of Women’s Health? A Qualitative Study on the Perspectives of Female Patients Seeking Care for the First Time in a Specialized Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature (Variable) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| to 50 | 33 | 20.9 |

| 51–60 | 27 | 17.1 |

| 61–70 | 55 | 34.8 |

| >70 | 43 | 27.2 |

| Education | ||

| elementary | 6 | 3.8 |

| vocational | 30 | 19 |

| secondary | 83 | 52.5 |

| higher education | 39 | 24.7 |

| Personal situation | ||

| in a relationship | 100 | 63.3 |

| single | 31 | 19.6 |

| widow | 27 | 17.1 |

| Professional status | ||

| professionally active | 54 | 34.2 |

| lack of employment | 9 | 5.7 |

| pension/disability pension | 95 | 60.1 |

| Place of residence | ||

| country | 18 | 11.4 |

| small town (to 30,000) | 24 | 15.2 |

| big city (>30,000) | 116 | 73.4 |

| UI Type n | SUI 49 | UUI 53 | MUI 56 | Kruskal–Wallis Test | Post Hoc Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | M | M | M | p | SUI | UUI | MUI | ||

| KHQ1 | 27.55 | 45.28 | 45.54 | 0.001 | SUI | <0.001 | <0.001 | p | |

| UUI | <0.001 | 0.950 | |||||||

| MUI | <0.001 | 0.950 | |||||||

| KHQ2 | 50.34 | 54.09 | 68.45 | 0.004 | SUI | 0.536 | 0.003 | p | |

| UUI | 0.536 | 0.015 | |||||||

| MUI | 0.003 | 0.015 | |||||||

| KHQ3 | 36.73 | 38.05 | 54.46 | 0.018 | SUI | 0.848 | 0.009 | p | |

| UUI | 0.848 | 0.014 | |||||||

| MUI | 0.009 | 0.014 | |||||||

| KHQ4 | 48.64 | 45.28 | 62.20 | 0.009 | SUI | 0.570 | 0.021 | p | |

| UUI | 0.570 | 0.003 | |||||||

| MUI | 0.021 | 0.003 | |||||||

| KHQ5 | 22.79 | 27.36 | 36.61 | 0.108 | n/a | ||||

| KHQ6 | 29.29 | 33.51 | 36.46 | 0.687 | n/a | ||||

| KHQ7 | 32.65 | 37.53 | 41.67 | 0.327 | n/a | ||||

| KHQ8 | 24.15 | 45.91 | 44.35 | 0.001 | SUI | <0.001 | <0.001 | p | |

| UUI | <0.001 | 0.761 | |||||||

| MUI | <0.001 | 0.761 | |||||||

| KHQ9 | 53.57 | 49.37 | 58.48 | 0.143 | n/a | ||||

| Severity n | Weak (1) 8 | Mild (2) 41 | Moderate (3) 55 | Severe (4) 54 | Kruskal–Wallis Test | Post Hoc Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | M | M | M | M | p | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

| KHQ 1 | 34.38 | 33.54 | 37.04 | 48.18 | 0.009 | (1) | 0.921 | 0.747 | 0.095 | p | |

| (2) | 0.921 | 0.438 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.747 | 0.438 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| (4) | 0.095 | 0.001 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| KHQ 2 | 25.00 | 38.21 | 55.56 | 80.00 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.186 | 0.002 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.186 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.002 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 3 | 18.75 | 19.11 | 40.43 | 68.18 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.975 | 0.052 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.975 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.052 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 4 | 33.33 | 34.15 | 48.15 | 72.73 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.936 | 0.137 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.936 | 0.011 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.137 | 0.011 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 5 | 12.50 | 10.16 | 23.15 | 51.82 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.830 | 0.320 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.830 | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.320 | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 6 | 44.44 | 12.17 | 26.83 | 53.99 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.116 | 0.378 | 0.635 | p | |

| (2) | 0.116 | 0.050 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.378 | 0.050 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | 0.635 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 7 | 19.44 | 20.60 | 33.95 | 56.16 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.913 | 0.162 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.913 | 0.019 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.162 | 0.019 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| KHQ 8 | 20.83 | 30.49 | 34.57 | 51.21 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.354 | 0.179 | 0.003 | p | |

| (2) | 0.354 | 0.465 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | 0.179 | 0.465 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| (4) | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| KHQ 9 | 15.63 | 35.98 | 54.78 | 71.97 | 0.001 | (1) | 0.011 | <0.001 | <0.001 | p | |

| (2) | 0.011 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| UI Duration n | To 2 Years 50 | 3–5 Years 41 | 6–10 Years 35 | Over 10 Years 32 | Spearman’s Rho | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | M | M | M | M | Rho | p |

| KHQ1 | 32.50 | 43.29 | 44.29 | 42.19 | 0.174 | 0.029 |

| KHQ2 | 43.33 | 57.72 | 68.57 | 69.79 | 0.349 | <0.001 |

| KHQ3 | 27.00 | 42.28 | 54.29 | 58.85 | 0.353 | <0.001 |

| KHQ4 | 37.33 | 51.22 | 60.48 | 68.23 | 0.388 | <0.001 |

| KHQ5 | 15.33 | 27.64 | 34.76 | 46.88 | 0.354 | <0.001 |

| KHQ6 | 21.30 | 34.29 | 36.23 | 41.67 | 0.230 | 0.024 |

| KHQ7 | 25.33 | 41.46 | 38.41 | 50.35 | 0.291 | <0.001 |

| KHQ8 | 31.00 | 43.09 | 39.05 | 44.27 | 0.164 | 0.040 |

| KHQ9 | 44.00 | 54.88 | 56.67 | 65.10 | 0.280 | <0.001 |

| KHQ | Rho | p |

|---|---|---|

| KHQ 1 | −0.244 | 0.002 |

| KHQ 2 | −0.291 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 3 | −0.430 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 4 | −0.407 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 5 | −0.390 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 6 | −0.463 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 7 | −0.403 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 8 | −0.318 | <0.001 |

| KHQ 9 | −0.434 | <0.001 |

| MINI-COPE | Active Coping | Helplessness | Seeking Support | Avoidant Behavior | Turn to Religion | Acceptance | Sense of Humor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p |

| KHQ 1 | −0.092 | 0.252 | 0.090 | 0.259 | −0.109 | 0.172 | 0.026 | 0.749 | 0.012 | 0.883 | 0.052 | 0.517 | −0.056 | 0.487 |

| KHQ 2 | −0.209 | 0.008 | 0.062 | 0.436 | −0.098 | 0.219 | 0.010 | 0.905 | 0.044 | 0.583 | −0.067 | 0.400 | −0.031 | 0.700 |

| KHQ 3 | −0.198 | 0.013 | 0.120 | 0.134 | −0.125 | 0.117 | 0.050 | 0.530 | 0.003 | 0.967 | −0.065 | 0.415 | −0.019 | 0.815 |

| KHQ 4 | −0.128 | 0.109 | 0.036 | 0.653 | −0.146 | 0.068 | −0.007 | 0.926 | 0.017 | 0.835 | −0.077 | 0.337 | −0.014 | 0.863 |

| KHQ 5 | −0.220 | 0.005 | 0.110 | 0.167 | −0.244 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.913 | 0.034 | 0.670 | −0.080 | 0.320 | −0.071 | 0.376 |

| KHQ 6 | −0.314 | 0.002 | 0.104 | 0.314 | −0.324 | 0.001 | −0.029 | 0.782 | −0.004 | 0.970 | −0.104 | 0.313 | −0.095 | 0.356 |

| KHQ 7 | −0.276 | <0.001 | 0.177 | 0.026 | −0.149 | 0.062 | 0.084 | 0.296 | 0.004 | 0.955 | −0.096 | 0.230 | −0.023 | 0.778 |

| KHQ 8 | −0.139 | 0.082 | 0.174 | 0.029 | −0.003 | 0.968 | 0.165 | 0.038 | 0.092 | 0.251 | 0.089 | 0.267 | −0.022 | 0.785 |

| KHQ 9 | −0.202 | 0.011 | 0.108 | 0.176 | −0.163 | 0.041 | 0.023 | 0.774 | 0.070 | 0.381 | −0.073 | 0.364 | −0.015 | 0.851 |

| Emotional Bond with Their Partner | Sexual Bond with Their Partner | Self-Assessment of Their Relationship with Their Partner | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p |

| KHQ 1 | −0.317 | 0.001 | −0.214 | 0.025 | −0.301 | 0.002 |

| KHQ 2 | 0.050 | 0.622 | 0.142 | 0.141 | 0.068 | 0.502 |

| KHQ 3 | 0.054 | 0.598 | 0.076 | 0.432 | 0.077 | 0.451 |

| KHQ 4 | 0.027 | 0.791 | 0.102 | 0.293 | 0.084 | 0.407 |

| KHQ 5 | −0.224 | 0.026 | −0.146 | 0.130 | −0.164 | 0.104 |

| KHQ 6 | −0.222 | 0.049 | −0.185 | 0.099 | −0.123 | 0.278 |

| KHQ 7 | −0.057 | 0.577 | 0.026 | 0.785 | −0.023 | 0.819 |

| KHQ 8 | −0.179 | 0.077 | −0.228 | 0.017 | −0.133 | 0.188 |

| KHQ 9 | −0.167 | 0.099 | −0.103 | 0.285 | −0.162 | 0.109 |

| Age | Education | Personal Situation | Professional Status | Place of Residence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ | Rho | p | Rho | p | H | p | H | p | H | p |

| KHQ 1 | 0.233 | 0.003 | −0.280 | <0.001 | 0.431 | 0.806 | 14.327 | 0.001 | 0.167 | 0.920 |

| KHQ 2 | −0.135 | 0.092 | −0.261 | 0.001 | 1.097 | 0.578 | 3.523 | 0.172 | 2.101 | 0.350 |

| KHQ 3 | −0.100 | 0.210 | −0.315 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.989 | 0.920 | 0.631 | 2.740 | 0.254 |

| KHQ 4 | −0.140 | 0.079 | −0.251 | 0.001 | 2.429 | 0.297 | 3.890 | 0.143 | 2.636 | 0.268 |

| KHQ 5 | 0.041 | 0.609 | −0.369 | <0.001 | 2.047 | 0.359 | 2.314 | 0.314 | 0.066 | 0.967 |

| KHQ 6 | 0.029 | 0.779 | −0.298 | 0.003 | 9.001 | 0.011 | 0.850 | 0.654 | 0.076 | 0.962 |

| KHQ 7 | −0.130 | 0.103 | −0.297 | <0.001 | 0.546 | 0.761 | 4.664 | 0.097 | 0.725 | 0.696 |

| KHQ 8 | 0.168 | 0.035 | −0.412 | <0.001 | 2.456 | 0.293 | 3.788 | 0.151 | 0.711 | 0.701 |

| KHQ 9 | −0.189 | 0.018 | −0.201 | 0.011 | 1.619 | 0.445 | 9.604 | 0.008 | 6.020 | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilarska, B.; Strojek, K.; Radzimińska, A.; Weber-Rajek, M.; Jarzemski, P. Assessing Quality of Life Among Women with Urinary Incontinence—Medical, Psychological, and Sociodemographic Determinants. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144839

Pilarska B, Strojek K, Radzimińska A, Weber-Rajek M, Jarzemski P. Assessing Quality of Life Among Women with Urinary Incontinence—Medical, Psychological, and Sociodemographic Determinants. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(14):4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144839

Chicago/Turabian StylePilarska, Beata, Katarzyna Strojek, Agnieszka Radzimińska, Magdalena Weber-Rajek, and Piotr Jarzemski. 2025. "Assessing Quality of Life Among Women with Urinary Incontinence—Medical, Psychological, and Sociodemographic Determinants" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 14: 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144839

APA StylePilarska, B., Strojek, K., Radzimińska, A., Weber-Rajek, M., & Jarzemski, P. (2025). Assessing Quality of Life Among Women with Urinary Incontinence—Medical, Psychological, and Sociodemographic Determinants. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(14), 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144839