The Impact of Fecal Diversion on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Adverse Gastrointestinal Toxicities †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

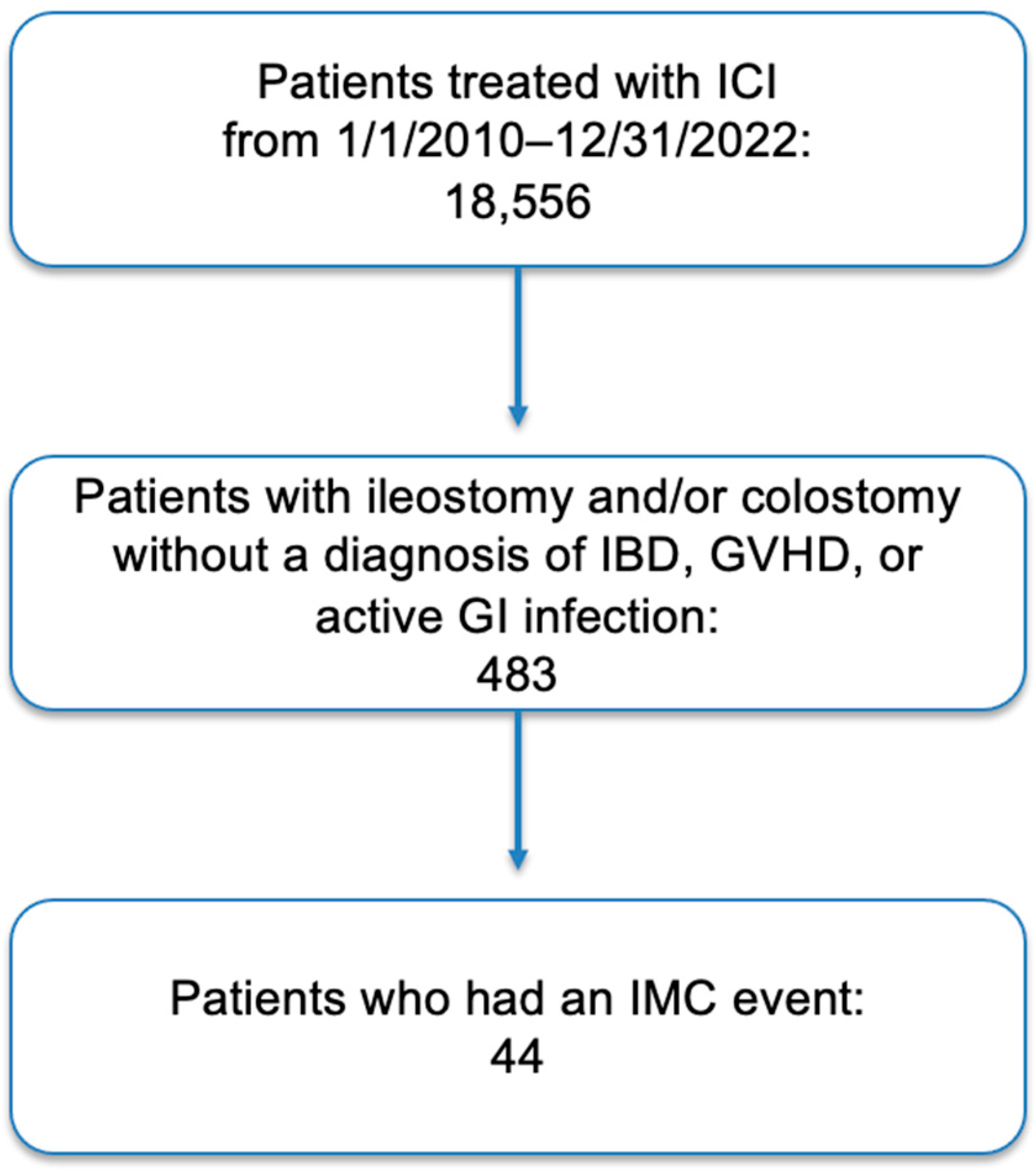

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Clinical Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population, Characteristics and Oncologic History

3.2. Characteristics and Treatment of Colitis

3.3. Treatment of Colitis per Group

3.4. Endoscopic Features

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O’Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, P.; Callejo, A.; Assaf, J.D.; Molina, G.; Lopez, D.E.; Garcia-Illescas, D.; Pardo, N.; Navarro, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Cedres, S.; et al. Overview of Checkpoint Inhibitors Mechanism of Action: Role of Immune-Related Adverse Events and Their Treatment on Progression of Underlying Cancer. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 875974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, R.; Cheema, A.; Khan, T.; Amirpour, A.; Paul, A.; Chaughtai, S.; Patel, S.; Patel, T.; Bramson, J.; Gupta, V.; et al. Adverse Effects of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (Programmed Death-1 Inhibitors and Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein-4 Inhibitors): Results of a Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2019, 11, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.S.; Wang, Y. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1301–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, P.; Bourassa-Blanchette, S.; Bishay, K.; Parlow, S.; Laurie, S.A.; McCurdy, J.D. The Risk of Diarrhea and Colitis in Patients with Advanced Melanoma Undergoing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Immunother. 2018, 41, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, M.; Wang, Y.; Rubio-Tapia, A.; Lim, J.K. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis and Hepatitis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wiesnoski, D.H.; Helmink, B.A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Choi, K.; DuPont, H.L.; Jiang, Z.D.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Sanchez, C.A.; Chang, C.C.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1804–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, T.A.; Dawes, A.J.; Graham, D.S.; Angarita, S.A.K.; Ha, C.; Sack, J. Rescue Diverting Loop Ileostomy: An Alternative to Emergent Colectomy in the Setting of Severe Acute Refractory IBD-Colitis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Ng, S.C. The Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Machiels, K.; Joossens, M.; Sabino, J.; De Preter, V.; Arijs, I.; Eeckhaut, V.; Ballet, V.; Claes, K.; Van Immerseel, F.; Verbeke, K.; et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2014, 63, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.; Tomov, V.T. Gut microbiota and IBD: Causation or correlation? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 2017, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Horisberger, K.; Portenkirchner, C.; Rickenbacher, A.; Biedermann, L.; Gubler, C.; Turina, M. Complete Recovery of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–induced Colitis by Diverting Loop Ileostomy. J. Immunother. 2020, 43, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0, DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS. 2003. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Azer, S.A.; Tuma, F. Infectious Colitis. StatPearls. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544325/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Hamdeh, S.; Micic, D.; Hanauer, S. Drug-Induced Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1759–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Nebhan, C.A.; Moslehi, J.J.; Balko, J.M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Long-term implications of toxicity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portenkirchner, C.; Kienle, P.; Horisberger, K. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis—A Clinical Overview of Incidence, Prognostic Implications and Extension of Current Treatment Options. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashash, J.G.; Francis, F.F.; Farraye, F.A. Diagnosis and Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hillock, N.T.; Heard, S.; Kichenadasse, G.; Hill, C.L.; Andrews, J. Infliximab for ipilimumab-induced colitis: A series of 13 patients. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 13, e284–e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; Clardy, J.; Xavier, R.J. Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K. The role of gut microbiota in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2018, 7, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Xiao, W. The Pathology and Physiology of Ileostomy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 842198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoodbhoy, M.; Patel, B.K.; Patel, K.; Bhatia, M.; Lee, C.N.; Moochhala, S.M. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis as a Target for Improved Post-Surgical Outcomes and Improved Patient Care: A Review of Current Literature. Shock 2021, 55, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, M.; Meserve, J.; Eisenstein, S.; Jairath, V.; McCurdy, J.; Singh, S. Temporary Faecal Diversion for Refractory Perianal and/or Distal Colonic Crohn’s Disease in the Biologic Era: An Updated Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winslet, M.C.; Andrews, H.; Allan, R.N.; Keighley, M.R. Fecal diversion in the management of Crohn’s disease of the colon. Dis. Colon Rectum 1993, 36, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgeerts, P.; Goboes, K.; Peeters, M.; Hiele, M.; Penninckx, F.; Aerts, R.; Kerremans, R.; Vantrappen, G. Effect of faecal stream diversion on recurrence of Crohn’s disease in the neoterminal ileum. Lancet 1991, 338, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, V.B.; Raffals, L.H.; Huse, S.M.; Vital, M.; Dai, D.; Schloss, P.D.; Brulc, J.M.; Antonopoulos, D.A.; Arrieta, R.L.; Kwon, J.H.; et al. Multiphasic analysis of the temporal development of the distal gut microbiota in patients following ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Microbiome 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.M.; George, B.D.; Jewell, D.P.; Warren, B.F.; Mortensen, N.J.; Kettlewell, M.G. Role of a defunctioning stoma in the management of large bowel Crohn’s disease. Br. J. Surg. 2000, 87, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslet, M.C.; Allan, A.; Poxon, V.; Youngs, D.; Keighley, M.R. Faecal diversion for Crohn’s colitis: A model to study the role of the faecal stream in the inflammatory process. Gut 1994, 35, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, F.; Medina, D.A.; Vera-Wolf, P.; Garrido, D. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cancer Immunotherapy: Enhancing Response and Managing Toxicity. Cancers 2023, 15, 4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, J.S.; Klotz, B.; Valdes, B.E.; Agudelo, G.M. The gut microbiota of Colombians differs from that of Americans, Europeans and Asians. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J.; et al. Daily sampling reveals personalized diet-microbiome associations in humans. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 789–802.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaulke, C.A.; Sharpton, T.J. The influence of ethnicity and geography on human gut microbiome composition. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1495–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 28 October 2024.

| Patient Characteristics, N = 44 | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 59 (31–86) |

| Sex, male | 25 (56.8) |

| Race, white | 37 (84.1) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino | 4 (9.0) |

| Cancer type | |

| Melanoma | 11 (25) |

| Genitourinary | 11 (25) |

| Lung | 1 (2.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 13 (29.5) |

| Endocrine | 2 (4.5) |

| Hematological | 1 (2.3) |

| Gynecologic | 3 (6.8) |

| Others | 2 (4.5) |

| Type of ICI | |

| Anti–CTLA-4 monotherapy | 3 (6.8) |

| Anti–PD-1/L1 monotherapy | 21 (47.7) |

| Combination anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-1/L1 | 20 (45.5) |

| Received abdominal or pelvic radiation before or during ICI treatment, N = 24 | 5 (20.8) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer, N = 13 | 3 (23.1) |

| Genitourinary cancer, N = 11 | 2 (18.2) |

| Stoma type | |

| Ileostomy | 12 (27.3) |

| Colostomy | 25 (56.8) |

| Both | 7 (15.9) |

| Stoma and IMC | |

| Stoma placed before IMC event | 28 (63.6) |

| Ileostomy | 6 (21.4) |

| Colostomy | 18 (64.2) |

| Both | 4 (14.2) |

| Stoma placed after an IMC event | 16 (36.4) |

| Ileostomy | 6 (37.5) |

| Colostomy | 7 (43.8) |

| Both | 3 (18.8) |

| Patient Outcomes, N = 44 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Group 1 | Group 2 | Total |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Duration of ICI exposure to IMC event, in days, median (IQR) | 310 (289–342) | 123 (97–143) | 234 (123–322) |

| Patients treated with steroids after IMC event | 12 | 14 | 26 (59.1) |

| Ileostomy | 5 | 4 | 9 (36) |

| Colostomy | 4 | 8 | 12 (46.2) |

| Both | 3 | 2 | 5 (20) |

| Number of steroid taper events, median (IQR) | 2.9 (2.1–3.5) | 4.7 (4.2–5.4) | 3.8 (2.9–4.9) |

| Patients treated with biologics after IMC event | 11 | 3 | 14 (31.8) |

| Ileostomy | 3 | 0 | 3 (21.4) |

| Colostomy | 6 | 2 | 8 (57) |

| Both | 2 | 1 | 3 (21.4) |

| Patients treated with FMT after IMC event | 1 | 1 | 2 (4.5) |

| Colostomy | 1 | 0 | 1 (2.3) |

| Both | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3) |

| Fecal calprotectin at the time of colitis, N= 20, median (IQR) | 378 (329–439) | 598 (525–664) | 493 (385–603) * |

| Patients who resumed ICI for cancer treatment | 19 | 11 | 30 (68.2) |

| Patients who had a recurrence of IMC event | 12 | 9 | 21 (47.7) |

| Patients who had a history of NSAID or PPI use | 7 | 4 | 11 (25%) |

| Cancer status | |||

| Stable disease | 4 | 5 | 9 (20.5) |

| No evidence of disease | 0 | 2 | 2 (4.5) |

| Progression of disease | 5 | 2 | 7 (15.9) |

| Patients expired | 11 | 13 | 24 (54.5) |

| Patient Treatment Outcomes per Group, N = 44 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group 1, N = 28; N (%) | Group 2, N = 16 N (%) | |

| Patients treated with steroids | 12 (42.9) | 14 (87.5) |

| Patients treated with biologics | 11 (39.3) | 3 (18.8) |

| Patients treated with FMT | 1 (3.6) | 1 (6.3) |

| Refractory IMC event post treatment | 12 (42.9) | 9 (56.3) |

| Descriptive Statistics of CTCAE Grade for Diarrhea Among Four Cohorts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Comparison | Univariate Logistic Model | Multivariate Logistic Model | ||||

| OR | p-Value | 95% CI | OR | p-Value | 95% CI | ||

| Gender | Female vs. Male | 0.76 | (0.35, 1.66) | 0.490 | |||

| Race | Black vs. White | 6.00 | (0.37, 98.3) | 0.209 | |||

| Race | Other vs. White | 1.05 | (0.34, 3.25) | 0.933 | |||

| Patient Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino vs. non-Hispanic or Latino | 0.25 | (0.06, 1) | 0.050 | 0.118 | (0.02, 0.62) | 0.011 |

| Type of diversion ostomy | ileostomy; ileostomy vs. colostomy | 3.35 | (1.3, 8.64) | 0.012 | 3.211 | (1.01, 10.18) | 0.048 |

| Type of diversion ostomy | colostomy; ileostomy vs. colostomy | 1.43 | (0.47, 4.31) | 0.526 | 1.533 | (0.45, 5.17) | 0.491 |

| Have ostomy at the time of ICI | no vs. yes | 2.44 | (1.1, 5.44) | 0.029 | 0.670 | (0.23, 1.98) | 0.469 |

| Have ostomy at the time of diarrhea colitis | no vs. yes | 6.67 | (2.54, 17.5) | <0.001 | 8.865 | (2.51, 31.31) | 0.0007 |

| Presence of take down stoma | no vs. yes | 0.66 | (0.25, 1.73) | 0.396 | |||

| cohort | After ICI vs. Before ICI | 3.58 | (1.15, 11.2) | 0.028 | 3.053 | (0.88, 10.57) | 0.078 |

| cohort | Before Tox vs. Before ICI | 1.19 | (0.42, 3.37) | 0.743 | 1.360 | (0.44, 4.20) | 0.592 |

| cohort | After Tox vs. Before ICI | 4.73 | (1.35, 16.6) | 0.015 | 2.846 | (0.73, 11.14) | 0.133 |

| Endoscopic Findings in Patients with Immune Mediated Colitis, N = 21 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1, N = 8 | |||

| Patient | Type of Stoma | Endoscopic Feature | Type of Inflammation |

| 1 | Both | Non- ulcerative | Chronic |

| 2 | Ileostomy | Non- ulcerative | Acute |

| 3 | Colostomy | Non- ulcerative | Acute |

| 4 | Colostomy | Normal mucosa | Chronic |

| 5 | Colostomy | Non- ulcerative | Unavailable |

| 6 | Both | Non- ulcerative | Acute |

| 7 | Ileostomy | Non- ulcerative | Chronic |

| 8 | Ileostomy | Normal mucosa | Lymphocytic |

| Group 2, N = 13 | |||

| 9 | Colostomy | Ulcerative | Chronic |

| 10 | Colostomy | Ulcerative | Acute |

| 11 | Colostomy | Non- ulcerative | Chronic |

| 12 | Colostomy | Non- ulcerative | Chronic |

| 13 | Colostomy | Ulcerative | Lymphocytic |

| 14 | Ileostomy | Ulcerative | Acute |

| 15 | Colostomy | Normal mucosa | Unavailable |

| 16 | Colostomy | Normal mucosa | Unavailable |

| 17 | Both | Ulcerative | Acute |

| 18 | Ileostomy | Ulcerative | Acute |

| 19 | Colostomy | Normal mucosa | Chronic |

| 20 | Ileostomy | Ulcerative | Acute |

| 21 | Colostomy | Normal mucosa | Unavailable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adames, S.M.; Naz, S.; Dai, J.; Wang, Y.; Shirwaikar Thomas, A. The Impact of Fecal Diversion on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Adverse Gastrointestinal Toxicities. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4711. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134711

Adames SM, Naz S, Dai J, Wang Y, Shirwaikar Thomas A. The Impact of Fecal Diversion on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Adverse Gastrointestinal Toxicities. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4711. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134711

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdames, Saltenat Moghaddam, Sidra Naz, Jianliang Dai, Yinghong Wang, and Anusha Shirwaikar Thomas. 2025. "The Impact of Fecal Diversion on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Adverse Gastrointestinal Toxicities" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4711. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134711

APA StyleAdames, S. M., Naz, S., Dai, J., Wang, Y., & Shirwaikar Thomas, A. (2025). The Impact of Fecal Diversion on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Adverse Gastrointestinal Toxicities. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4711. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134711