Comment on Barbu et al. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092

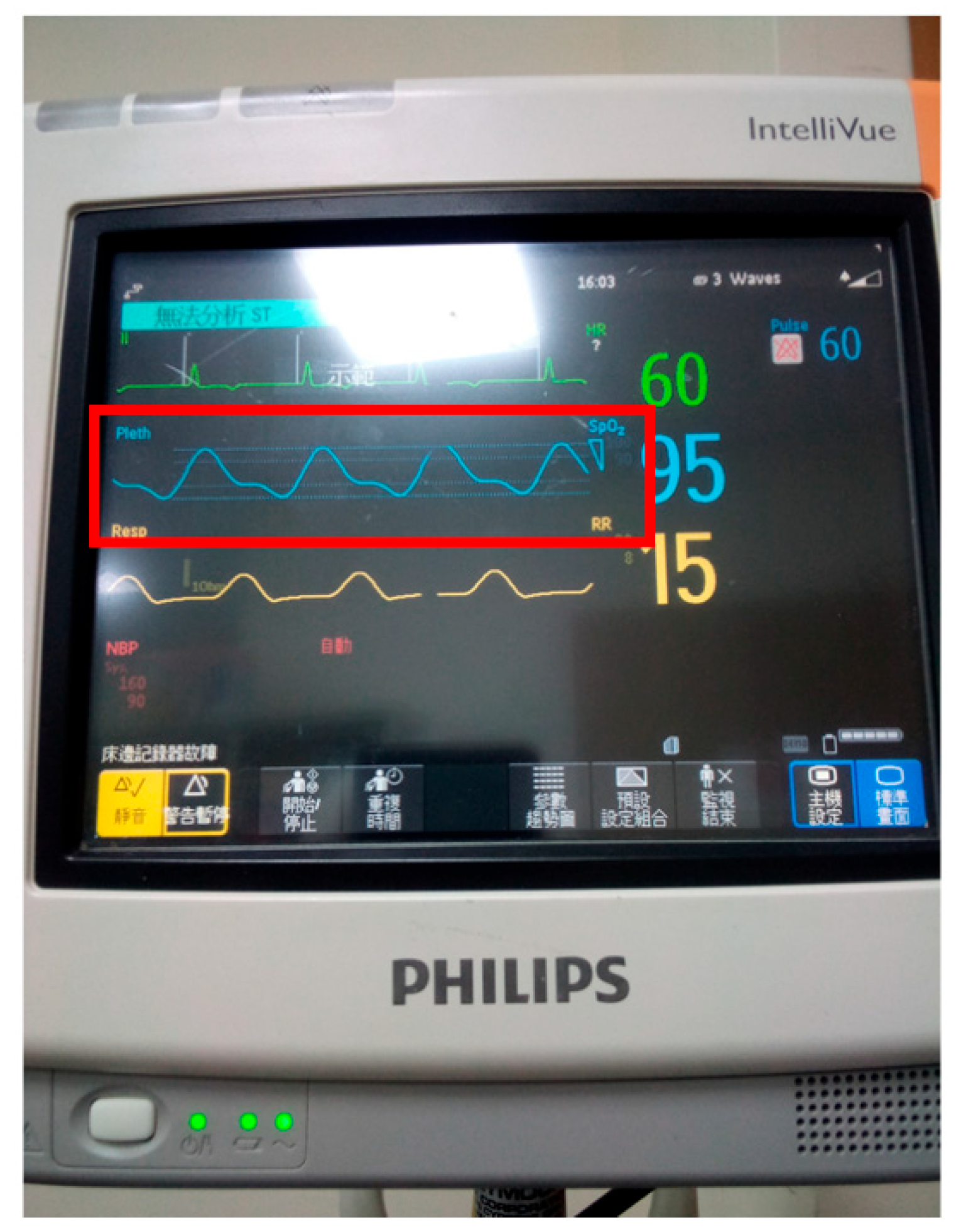

- The article provides both detailed CT imaging and operative reports for the patient but does not include a discussion of the physical examination findings for the upper and lower limbs [1]. Crucial evaluations, such as toe pule measurements (Figure 1), Doppler studies, and palpation findings, are essential for the early detection of possible peripheral artery diseases. This disease includes abdominal aortic aneurysms and aortic coarctation. These assessments, especially when compared to upper limb findings (as illustrated in Figure 2), provide valuable diagnostic insights. Unfortunately, such physical examination methods are often overlooked in clinical practice [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Additionally, Figure 3 shown here displays a real-time graph of vital signs, including ECG, pulse, and respiratory rate, captured digitally using a Philips® Patient Monitor.

- Pulse measurement is particularly important in patients with peripheral arterial disease, as they are at increased risk of sudden death. This is because inadequate physical examination may lead to inappropriate cardiopulmonary resuscitation, which could potentially cause a fatal aneurysmal rupture during chest compressions (i.e., cardiac massage).

- Regarding the etiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm, the article mentions that the cause of abdominal aortic aneurysm remains unclear [1]. An abdominal aneurysm refers to an abnormal, localized dilation of bulging of the abdominal aorta, the main artery that supplies blood to the lower part of the body. However, previous studies have indicated a strong association with long-standing uncontrolled hypertension, as reported previously [7,8,9]. We would appreciate the authors’ further elaboration on this point. Additionally, it is unclear whether the patient had a history of syphilis or any hereditary conditions such as Marfan syndrome. Patients with syphilis may develop syphilitic aortitis, which can lead to the formation of aortic aneurysm. Syphilitic aortitis occurs due to the chronic inflammatory response triggered by Treponema pallidum. The bacterium causes damage to the aortic wall, leading to the inflammation, thickening, and weakening of the aortic tissues [10]. Syphilitic aortitis is more likely, because it occurs in the tertiary stage, 30 years after diagnosis, but it is also rare, especially if a course of treatment with penicillin was administered, for which (or risk factors) there is no information in the patient’s personal history.

- Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects the connective tissue in the body, which provides structure and support to organs, blood vessels, bones, and tissues. The most serious complications of Marfan syndrome often involve the heart and blood vessels, particularly the aorta. Aortic aneurysm may occur, potentially leading to aortic dissection, which is life-threatening [11]. In addition, these patients have a characteristic phenotype [11,12]: they are tall and slim, with eye changes (cornea and/or lens), so they rarely go undiagnosed.

- It is important to note that Marfan syndrome is typically diagnosed early in life [12], making it unlikely that the condition significantly contributed to vascular changes in a patient of advanced age [1]. We agree that the diagnostic algorithm for the patient should have been presented more clearly and thoroughly, in which all differential–diagnostic and etiological dilemmas would be resolved [1]. A long-term patient with numerous comorbidities certainly has a resolution regarding the etiology of the mentioned diseases, which culminated in thrombosis and ischemia. The patient’s history of comorbidities clearly indicates that the patient is a long-term cardiology patient who has undergone all diagnostic evaluations [1]. Moreover, the possibility of other genetic and non-genetic factors influencing vascular pathology in elderly patients needs to be investigated.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Cercelaru, L.; Caragea, D.-C.; Vîlcea, I.-D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-Ș.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Vasile, L.; Țenea Cojan, T.Ș. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokangas, M.; Vakhitov, D.; Suominen, V.; Korhonen, J.; Huotari, M.; Verho, J.; Roning, J.; Mattila, V.M.; Romsi, P.; Oksala, N.; et al. Lower Limb Pulse Rise Time as a Marker of Peripheral Arterial Disease. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 2596–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boczar, K.E.; Boodhwani, M.; Beauchesne, L.; Dennie, C.; Chan, K.; Wells, G.A.; Coutinho, T. Estimated Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Is Associated With Faster Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Growth: A Prospective Cohort Study With Sex-Specific Analyses. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierling, W.; Matzner, J.; Apfelbeck, H.; Grothues, D.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Pfister, K. Pulse Wave Velocity for Risk Stratification of Patients with Aortic Aneurysm. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugajin, A.; Iwakoshi, S.; Ichihashi, S.; Inoue, T.; Nakai, T.; Kishida, H.; Chanoki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Mori, H.; Kichikawa, K. Prediction of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth After Endovascular Aortic Repair by Measuring Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 81, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Mian, O.; Boodhwani, M.; Beauchesne, L.; Dennie, C.; Chan, K.; Wells, G.A.; Rubens, F.; Coutinho, T. Combining Aortic Size With Arterial Hemodynamics Enhances Assessment of Future Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Expansion. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prisant, L.M.; Mondy, J.S., 3rd. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2004, 6, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, H.; Umemoto, T. ALICE (All-Literature Investigation of Cardiovascular Evidence) Group. Association of Hypertension with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Expansion. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 39, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, K.; Bhargava, P. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Am. Fam. Physician 2022, 106, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.A.; Ladich, E.R. Syphilitic Aortitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, S.G.; Almeida, A.G. Marfan syndrome revisited: From genetics to the clinic. Rev. Port. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 39, 215–226, (In English, Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, K.A.; Hove, H.; Kyhl, K.; Folkestad, L.; Gaustadnes, M.; Vejlstrup, N.; Stochholm, K.; Østergaard, J.R.; Andersen, N.H.; Gravholt, C.H. Prevalence, incidence, and age at diagnosis in Marfan Syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, S.-N.; Tsai, C.-H. Comment on Barbu et al. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134672

Wu S-N, Tsai C-H. Comment on Barbu et al. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134672

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Sheng-Nan, and Chung-Hung Tsai. 2025. "Comment on Barbu et al. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134672

APA StyleWu, S.-N., & Tsai, C.-H. (2025). Comment on Barbu et al. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?—A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134672