1. Introduction

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of inferior heel pain, accounting for nearly 80% of heel pain cases and affecting approximately 4% to 7% of the general population [

1]. It typically affects adults between 40 and 60 years of age and is more frequently observed in women [

2,

3]. Clinically, it presents as sharp, localized pain at the medial heel, especially during the first steps in the morning or after periods of rest. This presentation is often accompanied by biomechanical impairments such as limited ankle dorsiflexion, tightness in the posterior chain muscles, and altered gait mechanics [

2,

4].

The condition is degenerative in nature and results from repetitive micro-trauma to the plantar fascia. Its aetiology is multifactorial, with established risk factors including obesity, prolonged standing, inappropriate footwear, reduced flexibility, and participation in high-impact physical activities such as running [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These risk factors are especially relevant in Saudi Arabia, where national data indicate that over 35% of adults are classified as obese and more than 60% do not meet recommended levels of physical activity [

8,

9]. Additionally, large segments of the workforce, including healthcare professionals, educators, and retail employees, spend extended hours standing, which may further increase the risk of plantar fascia-related disorders [

10].

Plantar fasciitis is mainly diagnosed through a patient’s history and physical examination. Patients commonly report pain with the first steps in the morning, while clinical signs include localized tenderness at the medial calcaneal tubercle and limited ankle dorsiflexion [

2,

11]. The examination also includes assessing gait, muscle strength, and heel cord tightness [

11,

12]. It is important to rule out other causes of heel pain, such as fat pad atrophy, calcaneal stress fracture, or tarsal tunnel syndrome [

2,

11]. Imaging is not always required but can support the diagnosis when needed [

2,

11,

13]. Ultrasound is commonly used because it is safe, affordable, and effective in measuring plantar fascia thickness and guiding treatment [

13]. MRI may be used in more complex or unclear cases to rule out other conditions [

2,

11].

Conservative management is the primary treatment approach, with physiotherapy playing a central role. A range of evidence-based interventions is recommended, including stretching exercises for the plantar fascia and calf muscles, strengthening of foot and hip musculature, taping techniques, orthotic support, manual therapy, dry needling, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy [

11,

12,

14,

15]. Clinical practice guidelines developed by the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association support a multimodal approach that combines therapeutic exercise with manual therapy to improve clinical outcomes [

16]. When applied effectively, these interventions lead to symptom resolution in the majority of patients [

4,

17].

Despite the availability of high-quality evidence and guidelines, clinical practice often varies across different healthcare systems. For example, a national survey in the United Kingdom reported that physiotherapists frequently emphasized education and stretching but made limited use of interventions such as manual therapy and shockwave therapy [

18]. That UK-based study reflected practice patterns within a well-established healthcare system supported by the National Health Service, where access to postgraduate training, clinical technologies, and structured professional development is consistently available. In contrast, the physiotherapy profession in Saudi Arabia is evolving within a healthcare system undergoing major reforms [

19]. Institutional resources, training opportunities, and access to advanced technologies may differ across regions and clinical settings. To date, no national-level survey has examined how physiotherapists assess and manage plantar fasciitis in the Middle East, highlighting an important gap in the regional literature. Such differences in clinical practice may be influenced by variations in training, resource availability, and healthcare delivery models.

In the context of Saudi Arabia, limited access to continuing education, inconsistencies in postgraduate training, and unequal availability of clinical guidelines and technologies have been identified as systemic challenges facing physiotherapists [

20,

21]. These factors may contribute to variability in practice and hinder the consistent application of evidence-based care. High rates of musculoskeletal pain among Saudi working populations, such as healthcare workers, office staff, and schoolteachers, further underscore the need to strengthen musculoskeletal care delivery [

22,

23,

24]. This knowledge gap is particularly significant within the broader framework of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 healthcare transformation, which aims to expand allied health services and promote the use of evidence-based clinical practices [

19].

Although international guidelines provide clear recommendations, the extent to which physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia follow these recommendations in routine practice remains unclear. Understanding current practice patterns is essential for evaluating alignment with best-practice standards, identifying gaps in care, and informing targeted improvements in clinical training and health policy. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the assessment and management strategies employed by Saudi physiotherapists in treating plantar fasciitis and to evaluate the extent to which their practices reflect current evidence-based recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

This study employed a cross-sectional design and was conducted in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at Taif University, Saudi Arabia (Approval No. 44-015). All procedures involving human participants adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, all participants provided informed consent electronically after reviewing a detailed study information sheet embedded in the online questionnaire. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without consequence. All responses were collected anonymously, with no personally identifying information (e.g., names, IP addresses, or contact details) recorded, thereby ensuring both anonymity and data confidentiality.

2.2. Participants and Eligibility Criteria

The study targeted licensed physiotherapists currently practicing in Saudi Arabia who had encountered and/or treated patients with plantar fasciitis in their clinical practice. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) being a licensed physiotherapist currently employed in a clinical role within Saudi Arabia, and (2) having personally managed at least one patient with plantar fasciitis. There were no restrictions based on sex, nationality, or healthcare sector. Exclusion criteria included physiotherapists not currently engaged in clinical practice (e.g., full-time academics or administrators), students or interns who were not yet licensed, and individuals without any prior clinical involvement in the assessment or treatment of plantar fasciitis. Initial invitations were distributed through professional physiotherapy networks, institutional mailing lists, and social media platforms such as WhatsApp and X (formerly Twitter). Recipients were encouraged to forward the survey to other eligible colleagues to enhance response rates and ensure broader geographical coverage.

2.3. Questionnaire Development and Content

A structured, self-administered questionnaire was developed using the Google Forms platform. Parts 2 to 6 of the questionnaire were taken directly from a previously validated tool developed by Grieve and Palmer [

18], originally used in a UK-wide survey of physiotherapists managing plantar fasciitis. As all physiotherapy education programs in Saudi Arabia are delivered in English, and English is the primary language used in clinical documentation and communication among physiotherapists, the original English version was used without translation or cultural adaptation. The only modifications made were to the demographic and practice-related part, which were adjusted to reflect the Saudi healthcare context (e.g., type of institution and years of local experience). The questionnaire comprised six parts:

Participants’ characteristics (part 1): Collected demographic and professional data, including age, sex, nationality, clinical rank, years of experience, and primary workplace setting.

Description of physiotherapy services (part 2): Captured information on service accessibility, referral patterns, and average duration of assessment sessions.

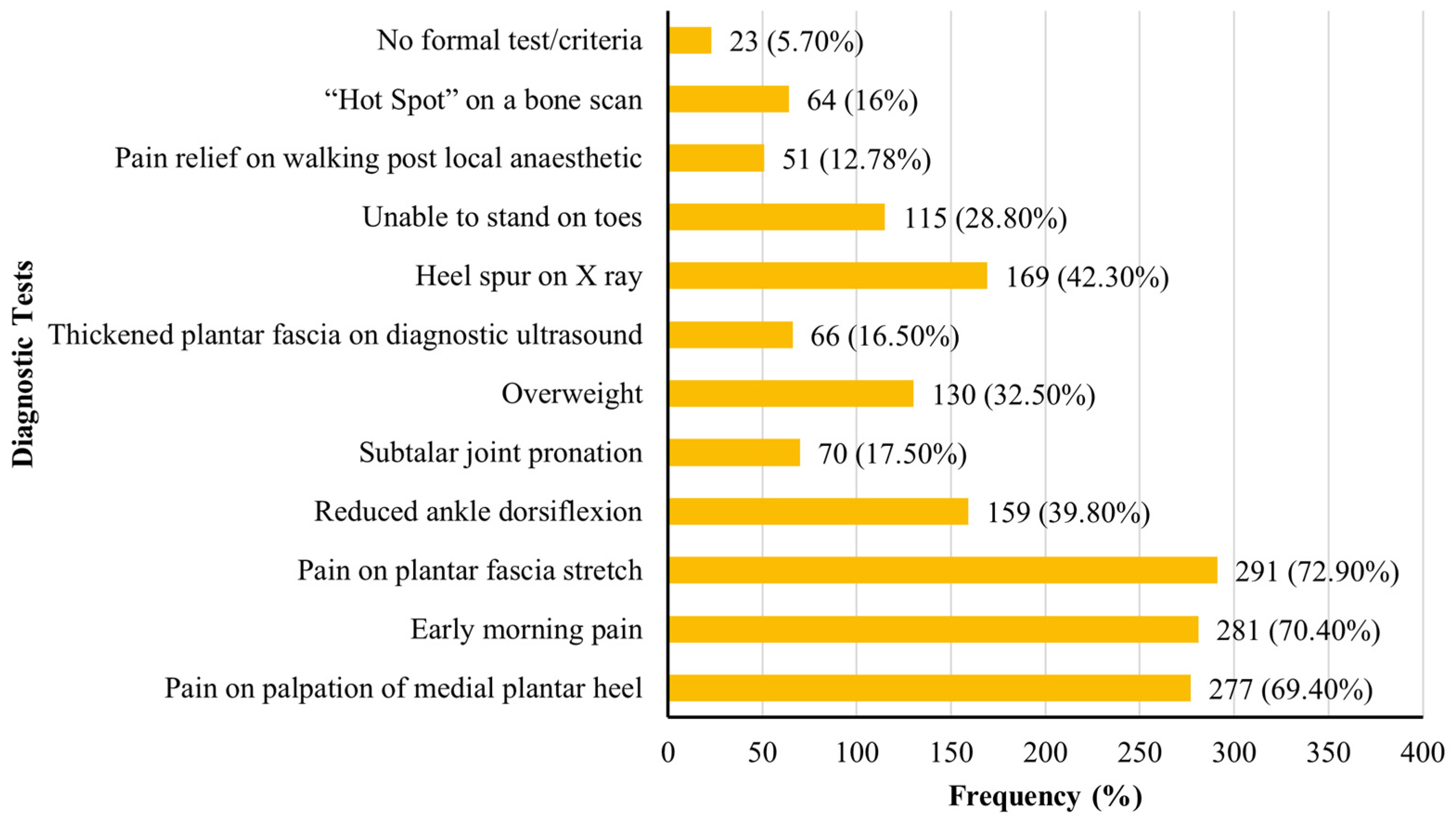

Diagnostic criteria (part 3): Explored the clinical criteria commonly used by participants to diagnose plantar fasciitis.

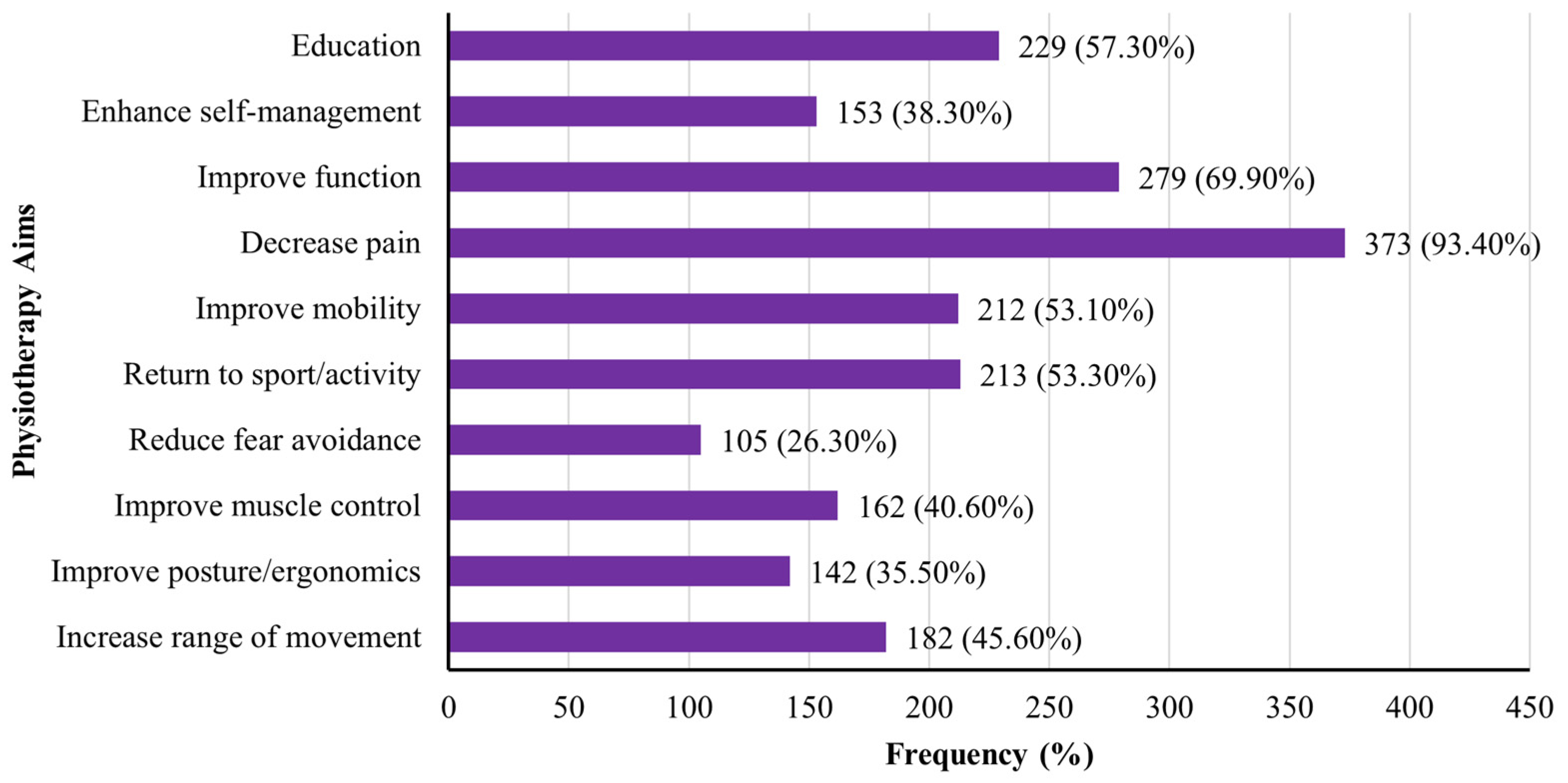

Goals of intervention (part 4): Assessed participants’ perspectives on the aims of physiotherapy in managing plantar fasciitis.

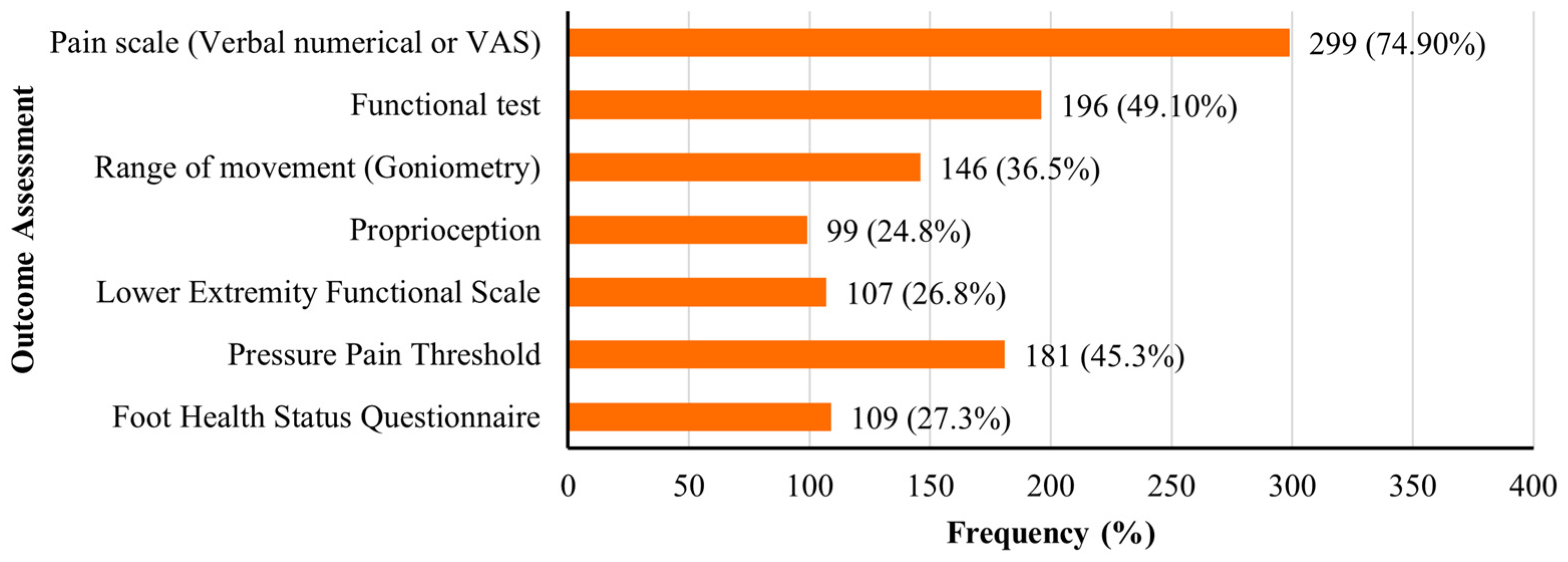

Assessment of outcome measures (part 5): Identified the tools and instruments used to evaluate treatment outcomes.

Intervention strategies (part 6): Identified the types and frequency of conservative physiotherapy interventions commonly employed in clinical practice.

2.4. Sample Size Estimation

A sample size calculation was performed using the Calculator.net sample size calculator. Based on the total number of licensed physiotherapists (n = 12,544) registered with the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties in Saudi Arabia, a minimum sample of 373 participants was required to achieve a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were exported to IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize and analyse the data. Continuous variables, such as age, were presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables, including survey response frequencies, were reported as absolute counts and percentages of valid responses. Given the descriptive nature of the study and its aim to explore current physiotherapy practices, no inferential statistical analyses were conducted. The use of descriptive statistics was deemed appropriate for the study objectives and is consistent with the approach adopted by the original study [

18] that developed the questionnaire utilized in the present research.

4. Discussion

This national cross-sectional study is the first to comprehensively investigate physiotherapy practices for the management of plantar fasciitis in Saudi Arabia. Several key findings emerged across domains of clinical care (description of physiotherapy services, diagnostic criteria, goals of intervention, assessment of outcome measures, and intervention strategies). First, the majority of patients were referred by orthopaedic specialists, although notable variability was observed in waiting times and the duration of assessment and treatment sessions, reflecting inconsistencies in service delivery. Second, diagnosis was primarily based on clinical signs such as medial heel tenderness, early morning pain, and pain during plantar fascia stretch, while imaging techniques were infrequently used, indicating a reliance on clinical examination. Third, physiotherapists commonly identified pain reduction, functional improvement, and patient education as the primary goals of intervention, consistent with current clinical guidelines. Fourth, outcome assessment predominantly involved pain scales and functional tests, whereas standardized tools such as FHSQ and LEFS were less frequently applied. Fifth, the most commonly used interventions were therapeutic exercises, stretching, strengthening, and education, while techniques such as dry needling, acupuncture, and hydrotherapy were rarely employed. Overall, these findings indicate substantial alignment with evidence-based guidelines but also reveal areas of variability in access to care, diagnostic methods, outcome assessment, and treatment implementation that warrant further standardization and professional development.

4.1. Description of Physiotherapy Services

Findings revealed that patients with plantar fasciitis in Saudi Arabia are most commonly referred to physiotherapy by orthopaedic specialists. While this pathway aligns with international patterns of care [

18], the study also found considerable variability in waiting times, with some patients receiving treatment within one week, while others experienced delays extending to several months. Such variation may be influenced by regional differences in service capacity, administrative processes, or healthcare infrastructure. Similarly, the duration of assessment and treatment sessions varied widely, ranging from 10 to 60 min, with a typical session lasting around 30 min. This variability in access and service structure may impact the consistency and quality of care delivered. Shorter or delayed sessions could limit comprehensive clinical evaluation, restrict implementation of tailored treatment plans, and reduce patient engagement, potentially contributing to inconsistent outcomes or prolonged recovery [

25]. In comparison, the UK survey by Grieve and Palmer [

18] also reported heterogeneity in session length, indicating a broader need for standardizing physiotherapy service delivery models for plantar fasciitis internationally. The limited integration of multidisciplinary care, with fewer than half of physiotherapists reporting collaborative work with other healthcare professionals, further highlights a gap in the holistic management of complex musculoskeletal conditions.

4.2. Diagnostic Criteria

Regarding diagnosis, physiotherapists in this study primarily relied on clinical indicators such as pain on palpation of the medial heel, early morning pain, and pain during plantar fascia stretching. These criteria are strongly supported by the APTA and American Family Physician guidelines, which recommend diagnosis based on patient history and physical examination rather than imaging [

11,

16]. The relatively limited use of diagnostic ultrasound, despite its high accuracy and non-invasive nature, suggests barriers such as restricted access to equipment or insufficient training [

13]. In contrast, some previous studies have demonstrated greater integration of diagnostic ultrasound in clinical practice, especially in specialized or sports medicine settings [

13]. The findings in this study reflect a clinical emphasis on traditional examination techniques, which are cost-effective and feasible in routine care but may lack the sensitivity needed to differentiate plantar fasciitis from other causes of heel pain. The underutilization of diagnostic ultrasound in the Saudi context may stem from broader systemic and educational challenges. These include limited availability of ultrasound machines in physiotherapy departments, the absence of structured ultrasound training in undergraduate programs, and minimal opportunities for continuing professional development in musculoskeletal imaging. Additionally, physiotherapists may lack authority to perform imaging in some healthcare settings, and national clinical protocols may not explicitly support their role in diagnostic imaging [

20].

4.3. Goals of Intervention

The primary therapeutic aims reported by physiotherapists included pain reduction (93.4%), improvement of physical function (69.9%), and provision of patient education (57.3%). These goals are consistent with those reported in the UK [

18] and reflect the priorities outlined in international guidelines [

11,

25]. The emphasis on education and function restoration aligns with the biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal care, which promotes active patient engagement, behaviour modification, and long-term self-management. Interestingly, goals such as addressing fear–avoidance behaviours and improving posture and ergonomics were less frequently cited, despite their potential relevance in chronic or recurrent plantar fasciitis. This may suggest a need for greater integration of psychosocial and ergonomic considerations into routine physiotherapy practice, as recommended by recent reviews [

25].

4.4. Assessment of Outcome Measures

In terms of outcome assessment, pain scales (such as VAS) and functional performance tests were the most frequently used measures. These tools are widely accepted in clinical practice for their simplicity and relevance to patient-cantered outcomes [

18,

26]. However, the underutilization of validated instruments such as FHSQ and the LEFS indicates an opportunity to enhance the comprehensiveness and comparability of outcome data. Standardized patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been recommended by international panels to monitor changes over time and facilitate inter-provider benchmarking [

25]. Barriers to the use of PROMs in physiotherapy practice may include time constraints, limited training on tool selection, and unfamiliarity with interpreting patient-reported scores. Additionally, many clinical settings in Saudi Arabia may lack integrated electronic health systems that facilitate routine PROM collection and documentation. In the absence of digital infrastructure or institutional mandates, clinicians may default to simpler tools that are quicker to administer, even if less comprehensive [

20,

21,

25].

4.5. Intervention Strategies

Exercise-based interventions were the most commonly employed treatment approach, including stretching, strengthening, and proprioceptive training. These findings are in agreement with current clinical guidelines [

11,

25] and supported by several randomized controlled trials demonstrating the efficacy of stretching the plantar fascia and posterior chain in improving pain and mobility [

15,

27,

28]. Strengthening programs targeting both foot intrinsic and proximal hip musculature have also been shown to improve gait parameters and functional capacity in patients with plantar fasciitis [

28]. The widespread use of exercise-based strategies in this study suggests a strong adherence to active, functionally oriented rehabilitation models. Education and self-management strategies were also frequently used by physiotherapists. This is encouraging, as patient education has been identified as a key component of effective musculoskeletal care, enabling individuals to manage activity levels, monitor symptoms, and understand the prognosis of plantar fasciitis [

14,

25]. Recommended self-management techniques, such as ball rolling and load management strategies, have demonstrated positive outcomes in previous studies and were commonly included in treatment plans in the current sample [

14]. However, the study also identified underutilization of several evidence-supported modalities. For instance, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, which is recommended in clinical guidelines for chronic or treatment-resistant plantar fasciitis [

11,

25], was used by fewer than two-thirds of physiotherapists. Possible reasons for this include the high cost of equipment acquisition, limited availability in non-specialized or public clinics, and the absence of insurance coverage or reimbursement in many settings. Additionally, shockwave therapy often requires formal training and specific credentialing, which may not be uniformly available to all physiotherapists. The lack of national clinical protocols detailing its indications, contraindications, and dosage parameters may also contribute to uncertainty in its application [

20,

25]. Manual therapy and joint mobilizations were employed by only about half, despite evidence suggesting benefit in selected patient populations [

17]. Possible explanations include limited access to equipment, institutional restrictions, insufficient training, or low patient demand. Similarly, low use of modalities such as dry needling, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, and heat therapy reflects both international trends and the inconsistent evidence supporting these approaches [

11,

25].

4.6. Implications

The findings of this study have important implications within the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, which prioritizes the enhancement of allied health services and the promotion of evidence-based care [

19]. The strong adherence to core physiotherapy principles, particularly in exercise and education-based interventions, reflects a positive trajectory. However, variability in the use of diagnostic tools, outcome measures, and advanced treatment modalities underscores the need for national clinical guidelines tailored to the Saudi healthcare context. Enhancing access to training in advanced interventions and promoting standardized outcome monitoring could improve care quality and consistency. Furthermore, integrating physiotherapists into multidisciplinary teams and expanding early referral pathways could address service accessibility gaps and improve patient outcomes. These findings have important implications for physiotherapy education and professional development in Saudi Arabia. Strengthening undergraduate curricula by incorporating comprehensive training in diagnostic imaging, standardized outcome measures, and guideline-recommended interventions such as shockwave therapy and manual therapy may better prepare future physiotherapists for clinical practice. In parallel, postgraduate programs and continuing professional development initiatives should reinforce these competencies among practicing clinicians to support the consistent application of evidence-based care across various healthcare settings.

4.7. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a self-administered online survey may introduce response bias, including potential overreporting of evidence-based practices. The sampling strategy, based on electronic distribution, may have excluded physiotherapists from remote or underrepresented regions. Additionally, the open and anonymous nature of the survey prevented the calculation of a response rate and assessment of sample representativeness. Second, although the core content of the questionnaire was based on a previously validated English version and deemed appropriate for the target population, no additional psychometric validation was conducted in the context of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, although the questionnaire specifically focused on plantar fasciitis, it is possible that some participants may have included patients with general heel pain rather than confirmed cases, particularly in the absence of imaging confirmation. This potential misclassification is particularly relevant given that referrals are often based on clinical presentation without imaging confirmation. Third, the study did not investigate the underlying factors influencing physiotherapists’ use of specific interventions. Factors such as equipment availability, institutional policies, clinician training, and financial or logistical constraints may play a significant role in treatment selection and implementation. Fourth, the inconsistent use of validated clinical outcome measures (e.g., PROMs) in real-world physiotherapy practice may affect the accuracy, reliability, and comparability of the reported data. Without standardized outcome tracking, variations in care quality and treatment impact may be difficult to interpret across settings. Finally, although the study provides a comprehensive national overview, it did not examine subgroup differences (e.g., by provider rank, years of experience, or healthcare sector). While the total sample size was sufficient for the main objectives, the uneven distribution across these subgroups limits the ability to draw reliable subgroup comparisons. Future studies with stratified sampling and subgroup-specific analyses are warranted.

5. Conclusions

This national study provides a detailed overview of physiotherapy practices for plantar fasciitis in Saudi Arabia. The results demonstrate substantial alignment with international clinical guidelines, particularly in diagnostic approaches, therapeutic goals, and the use of exercise and education-based interventions. Nevertheless, the findings also reveal variability in outcome assessment and limited use of certain evidence-based modalities. These insights highlight both the strengths and areas for improvement in current clinical practice. Future efforts should focus on promoting standardized care pathways, expanding access to training and technology, and conducting longitudinal or interventional studies to evaluate treatment outcomes. Enhancing clinical practice in the management of plantar fasciitis in Saudi Arabia requires the development of national clinical guidelines that are tailored to the local healthcare context and grounded in current evidence. At the same time, expanding access to structured continuing education programs, particularly those focused on advanced physiotherapy interventions such as shockwave therapy and manual therapy, may support greater consistency in the delivery of care. The routine use of validated patient-reported outcome measures, including the FHSQ and LEFS, should also be prioritized to facilitate more standardized and comprehensive monitoring of treatment outcomes. Strengthening the involvement of physiotherapists in multidisciplinary teams and establishing efficient referral pathways may help address existing gaps in service accessibility and coordination. At the health system level, incorporating these strategies into national rehabilitation frameworks, institutional protocols, and licensure standards could promote consistency, improve care quality, and align physiotherapy services with internationally recognized best practices. Collectively, these measures have the potential to advance musculoskeletal health outcomes and optimize the effectiveness of physiotherapy care for individuals with plantar fasciitis throughout Saudi Arabia.