Assessment of the Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Myopia from the City of Varna

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Aged 8 to 16 years.

- (2)

- Corrected myopia with optical aids, including monofocal glasses, mono- or multifocal soft contact lenses, and ortho-K lenses.

- (3)

- Refractive error of −0.50 to −5.50 D and cylindrical refraction not more than 0.50 D.

- (4)

- Monocular best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) for both eyes no less than 0.00 logMAR.

- (5)

- No history of ocular surgery or trauma.

- (6)

- Absence of systemic diseases that could affect the quality of vision,

- (7)

- No reported psychiatric disorders.

- (8)

- Verbal patients.

- (9)

- With parents/guardians who signed a declaration of informed consent.

- Name: ______________________________________ Date: _______________

- Best corrected visual acuity: ________________________________________

- Directions:

| Category | Statement | Assessment | |

| Attitude | I like wearing glasses/contact lenses. | |

| Handling | I can easily clean and care for my glasses/contact lenses. My glasses/contact lenses are easy to put on and take off. My glasses/contact lenses get lost or break easily. My glasses/contact lenses fall off my face. | ||

| Overall vision | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I have trouble seeing clearly. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my vision is very clear. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my vision is blurry. | ||

| Perception | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my friends make fun of me. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my friends want to wear glasses/contact lenses too. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my friends like the way I look. | ||

| Symptoms | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my eyes hurt. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my nose, ears, or head hurt. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my eyes itch, burn, or feel dry. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, my eyes feel good. | ||

| Near distance vision | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I have no trouble seeing the computer screen or playing video games. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I have troubles reading. | ||

| Appearance | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I like the way I look. I don’t like how I look with glasses/contact lenses. If I wore contacts/glasses, I would look better. | ||

| Far distance vision | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I can see clearly far away. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I have trouble seeing movies or when looking far away. | ||

| School environment | When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I perform better in school. When I wear glasses/contact lenses, I do better on tests. | ||

| Activities and hobbies | I have never had a problem wearing glasses/contact lenses when playing outdoors. My glasses/contact lenses bother me when I play sports, dance, or do other activities. |

| Statement | 0 Not True or Hardly Always True |

1

Somewhat True or Sometimes True | 2 Very True or Often True | ||

| 1. I get headaches when I’m at school. | |||||

| 2. I worry about whether other people like me. | |||||

| 3. I am nervous. | |||||

| 4. I get stomachaches at school. | |||||

| 5. I worry about being as good as other children. | |||||

| 6. I’m worried about going to school. | |||||

| 7. When I get scared, I sweat a lot. | |||||

| 8. I find it difficult to talk to people I don’t know well. | |||||

| 9. I feel shy around people I don’t know well. | |||||

| 10. I am afraid to go to school. | |||||

| 11. When I get scared, I feel dizzy. | |||||

| 12. I feel nervous when I am with other children or adults and have to do something while they are watching me (for example: reading aloud, talking, playing a game, playing sports). | |||||

| 13. I feel nervous when I go to parties, dances, or other places where there will be people I don’t know well. | |||||

| 14. I am shy. | |||||

- PART 2. (To be completed by parent)

| Category | Statement | Assessment |

| Attitude | Overall, how does your child feel about their optical correction device? | ||

| Handling | How does your child feel about their vision correction device (putting on/taking off, cleaning, fear of breakage, etc.)? | ||

| Overall vision | How does your child feel about their vision? | ||

| Perception | How does your child feel about their friends’ impressions of them because of their vision correction device? | ||

| Symptoms | How does your child feel about the comfort of their eyes? | ||

| Appearance | How does your child feel about their appearance? | ||

| School environment | How does your child cope in a school environment while wearing a corrective aid? | ||

| Activities and hobbies | How does your child feel about participating in activities while wearing vision correction? |

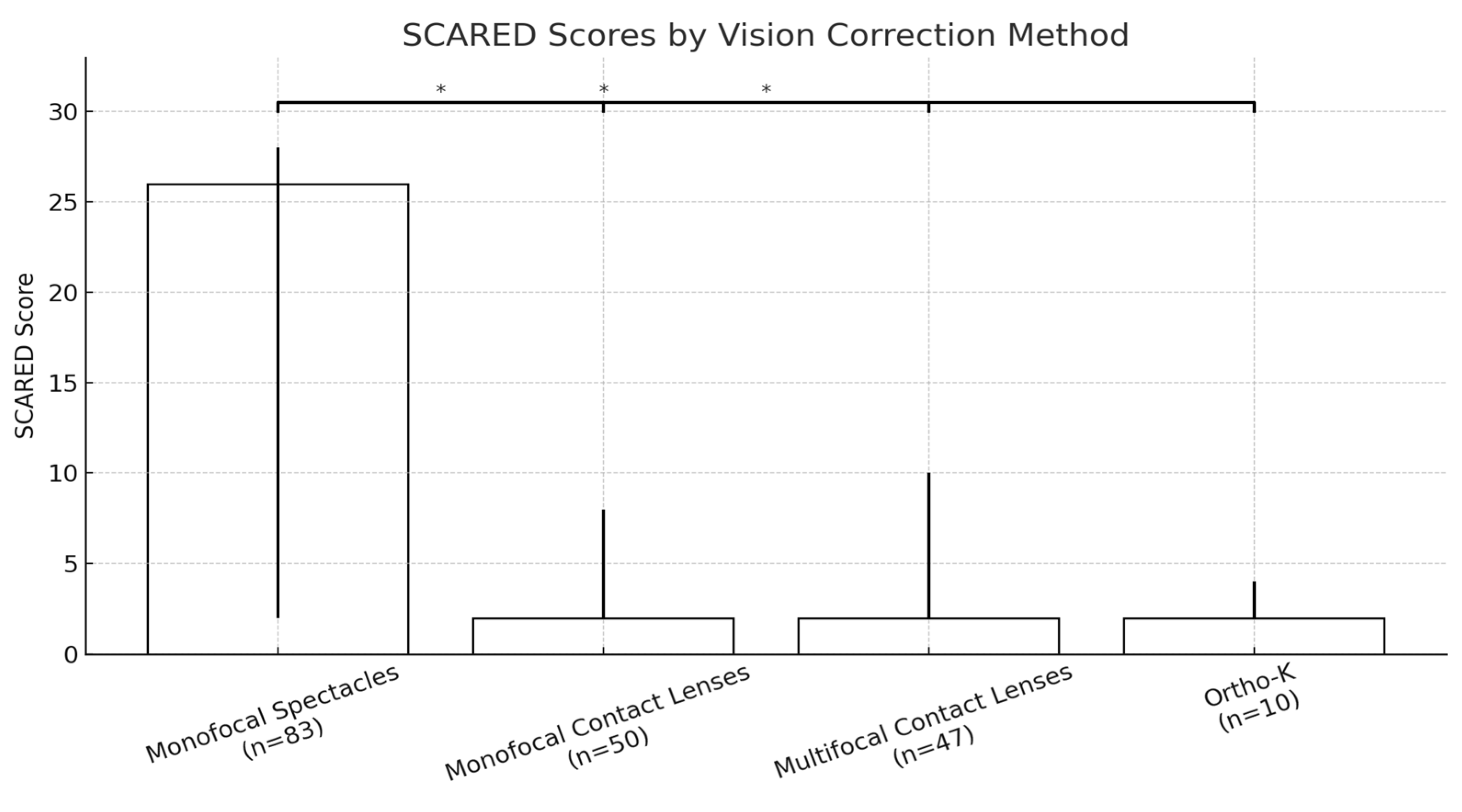

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sankaridurg, P.; Tahhan, N.; Kandel, H.; Naduvilath, T.; Zou, H.; Frick, K.D.; Marmamula, S.; Friedman, D.S.; Lamoureux, E.; Keeffe, J.; et al. IMI impact of myopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Vision. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/328717/9789241516570-eng.pdf?sequence=18 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). In The Impact of Myopia and High Myopia: A Report of the Joint World Health Organization–Brien Holden Vision Institute, Global Scientific Meeting on Myopia; University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://myopiainstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Myopia_report_020517.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Holden, B.A.; Fricke, T.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Wong, T.Y.; Naduvilath, T.; Resnikoff, S. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Tkatchenko, A.V. A review of current concepts of the etiology and treatment of myopia. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.C.; Chuang, M.N.; Choi, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, G.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Jonas, J.B.; Cheung, C.M.G. Update in myopia and treatment strategy of atropine use in myopia control. Eye 2019, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, P.; Tan, Q. Myopia and orthokeratology for myopia control. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walline, J.J. Myopia control: A review. Eye Contact Lens 2016, 42, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhirar, N.; Dudeja, S.; Duggal, M.; Gupta, P.C.; Jaiswal, N.; Singh, M.; Ram, J. Compliance to spectacle use in children with refractive errors-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Zhu, J.; Guan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, D.; Shi, Y. Factors associated with the spectacle wear compliance among primary school students with refractive error in rural China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2023, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Hatt, S.R.; Leske, D.A.; Holmes, J.M. Spectacle wear in children reduces parental health-related quality of life. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2011, 15, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walline, J.J.; Jones, L.A.; Sinnott, L.; Chitkara, M.; Coffey, B.; Jackson, J.M.; Manny, R.E.; Rah, M.J.; Prinstein, M.J.; ACHIEVE Study Group. Randomized trial of the effect of contact lens wear on self-perception in children. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2009, 86, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, D.D.; Turhan, S.A.; Toker, E. Daily disposable contact lens use in adolescents and its short-term impact on self-concept. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerullo, C.; Møller, F.; Ewan, R.; Nørgaard, B.; Jakobsen, T.M. Vision-related quality of life in children: Cross-cultural adaptation and test–retest reliability of the Danish version of the paediatric refractive error profile 2. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, e970–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birmaher, B.; Khetarpal, S.; Brent, D.; Cully, M.; Balach, L.; Kaufman, J.; Neer, S.M. The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.L., III. Optical treatment strategies to slow myopia progression: Effects of the visual extent of the optical treatment zone. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 114, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ma, X.; Liu, L.; Cho, P. Vision-related quality of life of Chinese children undergoing orthokeratology treatment compared to single vision spectacles. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeda, A.R.; Pérez-Sánchez, B.; Suárez, M.D.P.C.; Garrido, F.L.P.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, R.; Villa-Collar, C. MiSight Assessment Study Spain: A comparison of vision-related quality-of-life measures between MiSight contact lenses and single-vision spectacles. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, S99–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chang, S.; Jiang, J.; Yu, M.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, X. Association between vision-related quality of life and mental health status in myopia children using various optical correction aids. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, M.J.; Boland, B.; McAlinden, C. Vision-related quality of life with myopia management: A review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2022, 45, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.B.; Stapleton, F.; Erickson, P.; Du Toit, R.; Giannakopoulos, E.; Holden, B. Development and validation of a multidimensional quality-of-life scale for myopia. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2004, 81, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, M.; Tan, X.; Liu, Z.; Luo, L.; Liu, Y. Effect of Myopia Severity on the Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Their Parents. Curr. Eye Res. 2023, 48, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chan, V.F.; Virgili, G.; Mavi, S.; Pundir, S.; Singh, M.K.; She, X.; Piyasena, P.; Clarke, M.; Whitestone, N.; et al. Impact of vision impairment and ocular morbidity and their treatment on quality of life in children: A systematic review. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, S. Effects of myopia on health-related quality of life in adolescents: A population-based cross-sectional causal empirical survey. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024, 9, e001730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawistowska, J.; Powierza, K.; Sawicka-Powierza, J.; Macdonald, J.; Czerniawska, M.; Macdonald, A.; Przystupa, Z.; Bakunowicz-Łazarczyk, A. Health-related quality of life using the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire among adolescents with high myopia. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walline, J.J.; Jones, L.A.; Rah, M.J.; Manny, R.E.; Berntsen, D.A.; Chitkara, M.; Gaume, A.; Kim, A.; Quinn, N.; Clip Study Group. Contact Lenses in Pediatrics (CLIP) Study: Chair time and ocular health. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2007, 84, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rah, M.J.; Walline, J.J.; Jones-Jordan, L.A.; Sinnott, L.T.; Jackson, J.M.; Manny, R.E.; Coffey, B.; Lyons, S.; ACHIEVE Study Group. Vision specific quality of life of pediatric contact lens wearers. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010, 87, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santodomingo-Rubido, J.; Villa-Collar, C.; Gilmartin, B.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, R. Myopia control with orthokeratology contact lenses in Spain: A comparison of vision-related quality-of-life measures between orthokeratology contact lenses and single-vision spectacles. Eye Contact Lens 2013, 39, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, Z. Investigation of the effect of orthokeratology lenses on quality of life and behaviors of children. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlinden, C.; Lipson, M. Orthokeratology and Contact Lens Quality of Life Questionnaire (OCL-QoL). Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, S.; Wilson, A.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Appearance anxiety and social anxiety: A mediated model of self-compassion. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Manny, R.E.; Hyman, L.; Fern, K.; Comet Group. The relationship between self-esteem of myopic children and ocular and demographic characteristics. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2002, 79, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Manny, R.E.; Weissberg, E.; Fern, K.D. Myopia, contact lens use and self-esteem. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2013, 33, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Congdon, N.; Burnett, A.; Frick, K. The impact of uncorrected myopia on individuals and society. Community Eye Health 2019, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rose, K.; Harper, R.; Tromans, C.; Waterman, C.; Goldberg, D.; Haggerty, C.; Tullo, A. Quality of life in myopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeter, D.Y.; Bozali, E.; Cicek, A.U. Comparison of Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety Levels of Adolescents Who Wear Spectacles and Who Do Not. Turk. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 15, 862–871. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Gender | 101 f; 89 m |

| Age | Mean age—11.65, youngest—8, oldest—16 |

| Refractive error | Myopia (from −1.00 to −5.50 D) |

| Indicator | Monofocal Spectacles | Monofocal Contact Lenses | Multifocal Contact Lenses | Ortho-K Lenses | x2/F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCVA right eye, LogMAR | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.978 | 0.435 |

| BCVA left eye, LogMAR | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.703 | 0.834 |

| Category | The Cronbach’s Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monofocal Spectacles | Monofocal Contact Lenses | Multifocal Contact Lenses | Ortho-K Lenses | |

| Attitude | 0.798 | 0.732 | 0.623 | 0.785 |

| Handling | 0.743 | 0.712 | 0.789 | 0.812 |

| Overall vision | 0.815 | 0.765 | 0.719 | 0.832 |

| Perception | 0.892 | 0.609 | 0.612 | 0.645 |

| Symptoms | 0.840 | 0.756 | 0.731 | 0.774 |

| Near distance vision | 0.712 | 0.832 | 0.845 | 0.812 |

| Appearance | 0.895 | 0.604 | 0.603 | 0.645 |

| Far distance vision | 0.891 | 0.603 | 0.612 | 0.892 |

| School environment | 0.989 | 0.645 | 0.813 | 0.634 |

| Activities and hobbies | 0.882 | 0.621 | 0.671 | 0.872 |

| Category | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monofocal Spectacles vs. Monofocal Contact Lenses | Ortho-K vs. Monofocal Spectacles | Ortho-K vs. Monofocal Contact Lenses | Ortho-K vs. Multifocal Contact Lenses | |

| Attitude | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| Handling | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Overall vision | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

| Perception | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Symptoms | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Near distance vision | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Appearance | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.43 | 0.70 |

| Far distance vision | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.75 |

| School environment | 0.32 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.87 |

| Activities and hobbies | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| Category | The Cronbach’s Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monofocal Spectacles | Monofocal Contact Lenses | Multifocal Contact Lenses | Ortho-K Lenses | |

| Symptoms (I get headaches when I’m at school; I get stomachaches at school.; When I get scared, I sweat a lot.; When I get scared, I feel dizzy.) | 0.892 | 0.778 | 0.732 | 0.774 |

| Shyness (I find it difficult to talk to people I don’t know well.; I am nervous.; I feel shy around people I don’t know well.; I feel nervous when I go to parties, dances, or other places where there will be people I don’t know well.; I am shy.) | 0.854 | 0.692 | 0.619 | 0.702 |

| Performance (I worry about whether other people like me.; I worry about being as good as other children.; I’m worried about going to school.; I am afraid to go to school.; I feel nervous when I am with other children or adults and have to do something while they are watching me (for example: reading aloud, talking, playing a game, playing sports).) | 0.889 | 0.634 | 0.742 | 0.753 |

| 0–164 | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 190 | Monofocal Spectacles (n = 83) | Monofocal Contact Lenses (n = 50) | Multifocal Contact Lenses (n = 47) |

Ortho-K Lenses

(n = 10) | |

| Overall score | 35 | 107 | 12 | 25 | 28 |

| Attitude | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| Handling | 7.5 | 8 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 |

| Overall vision | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 |

| Perception | 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Symptoms | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Near distance vision | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Appearance | 2.5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Far distance vision | 4 | 4 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 |

| School environment | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Activities and hobbies | 4 | 4 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoeva, M.; Stefanova, D.; Boyadzhiev, D.; Zlatarova, Z.; Nencheva, B.; Radeva, M. Assessment of the Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Myopia from the City of Varna. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134546

Stoeva M, Stefanova D, Boyadzhiev D, Zlatarova Z, Nencheva B, Radeva M. Assessment of the Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Myopia from the City of Varna. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134546

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoeva, Mariya, Daliya Stefanova, Dobrin Boyadzhiev, Zornitsa Zlatarova, Binna Nencheva, and Mladena Radeva. 2025. "Assessment of the Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Myopia from the City of Varna" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134546

APA StyleStoeva, M., Stefanova, D., Boyadzhiev, D., Zlatarova, Z., Nencheva, B., & Radeva, M. (2025). Assessment of the Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Myopia from the City of Varna. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134546