Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports

Abstract

1. Introduction

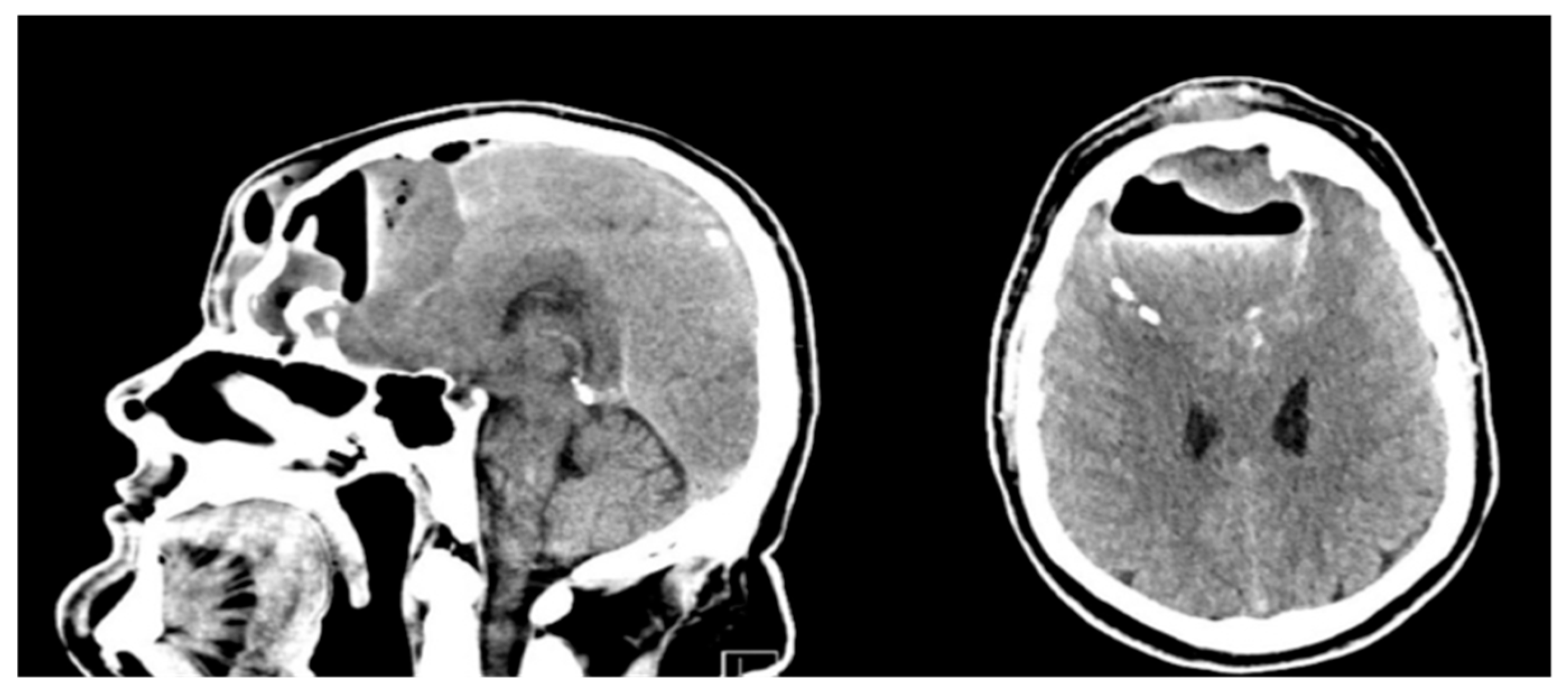

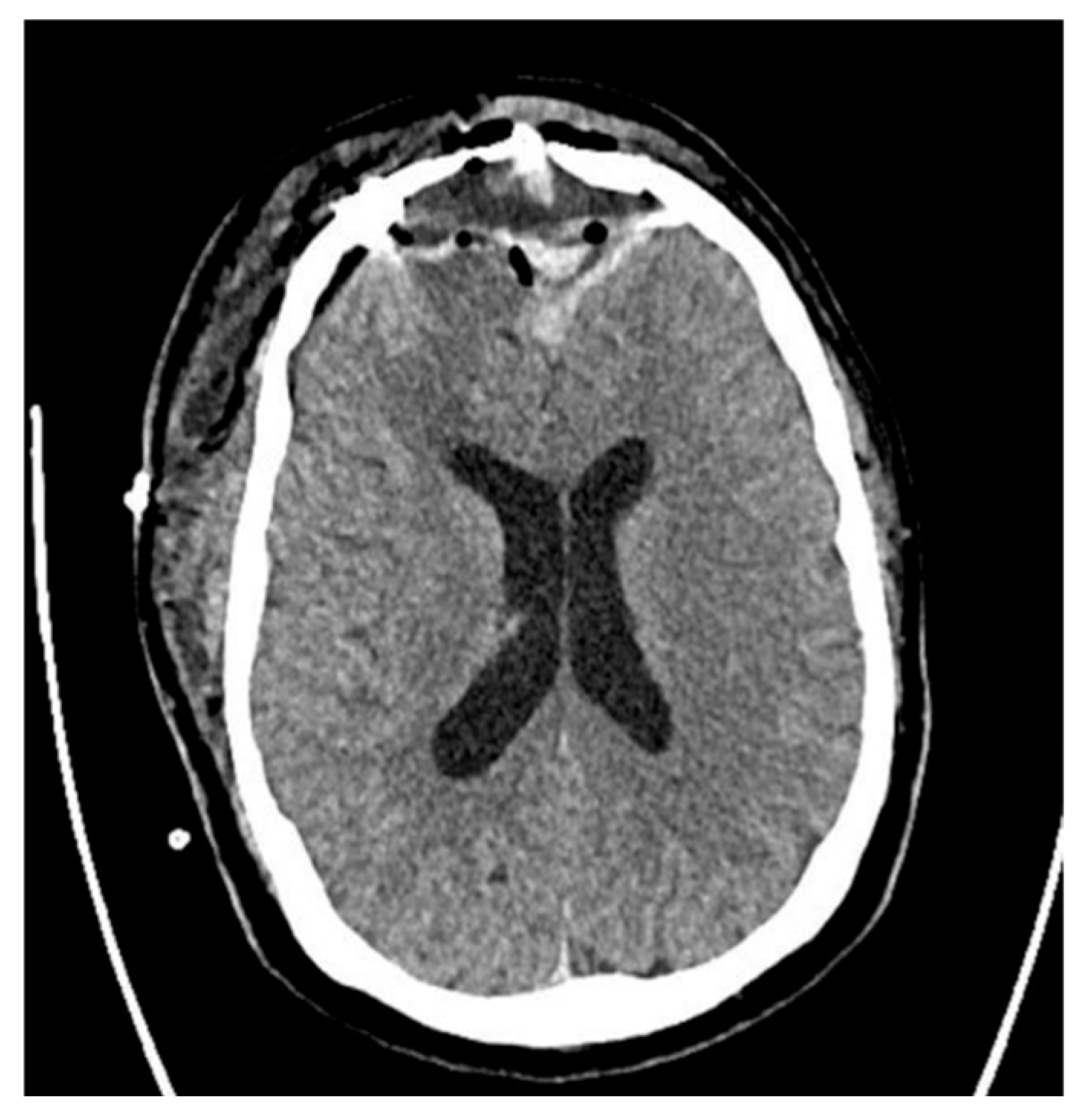

2. Case Presentation

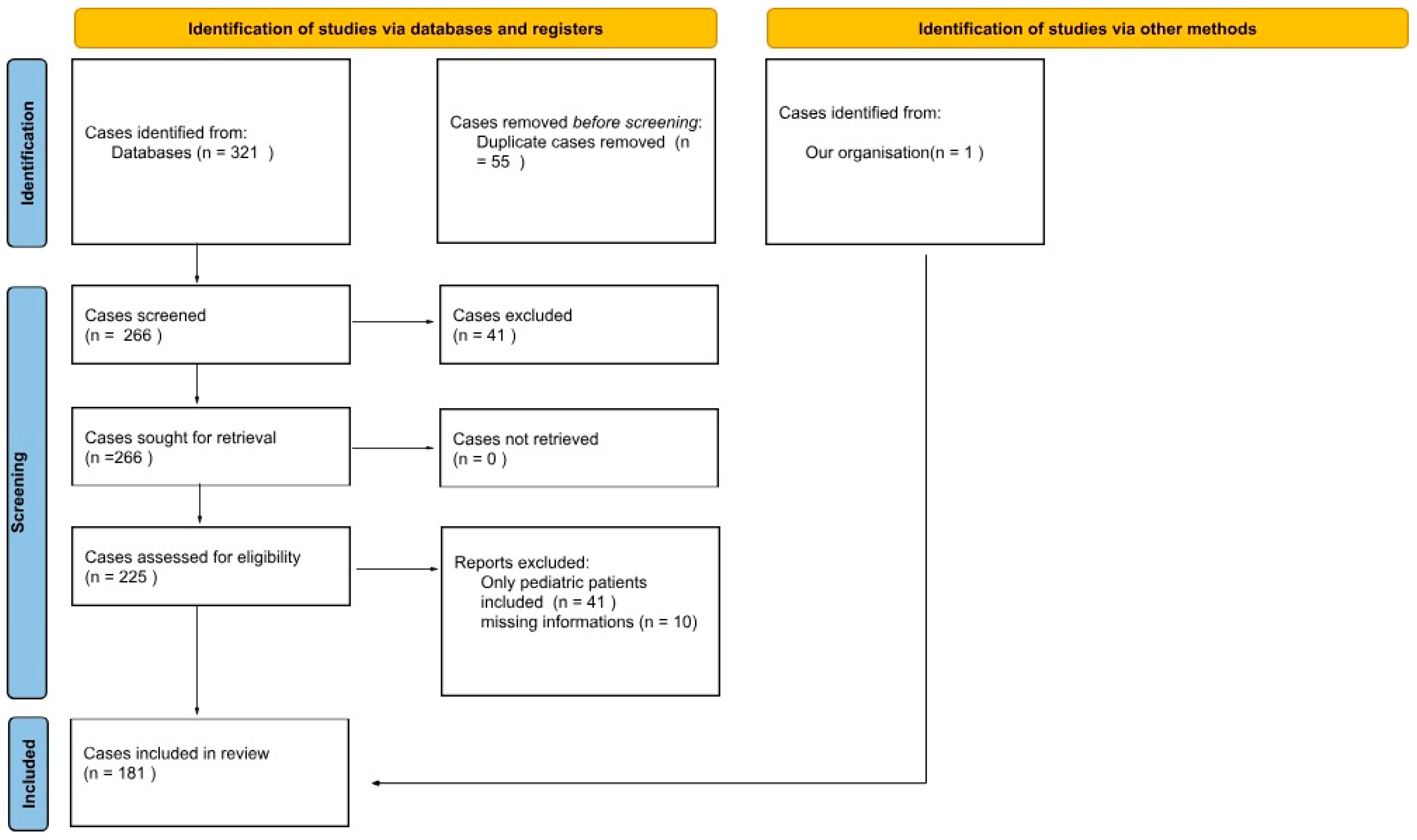

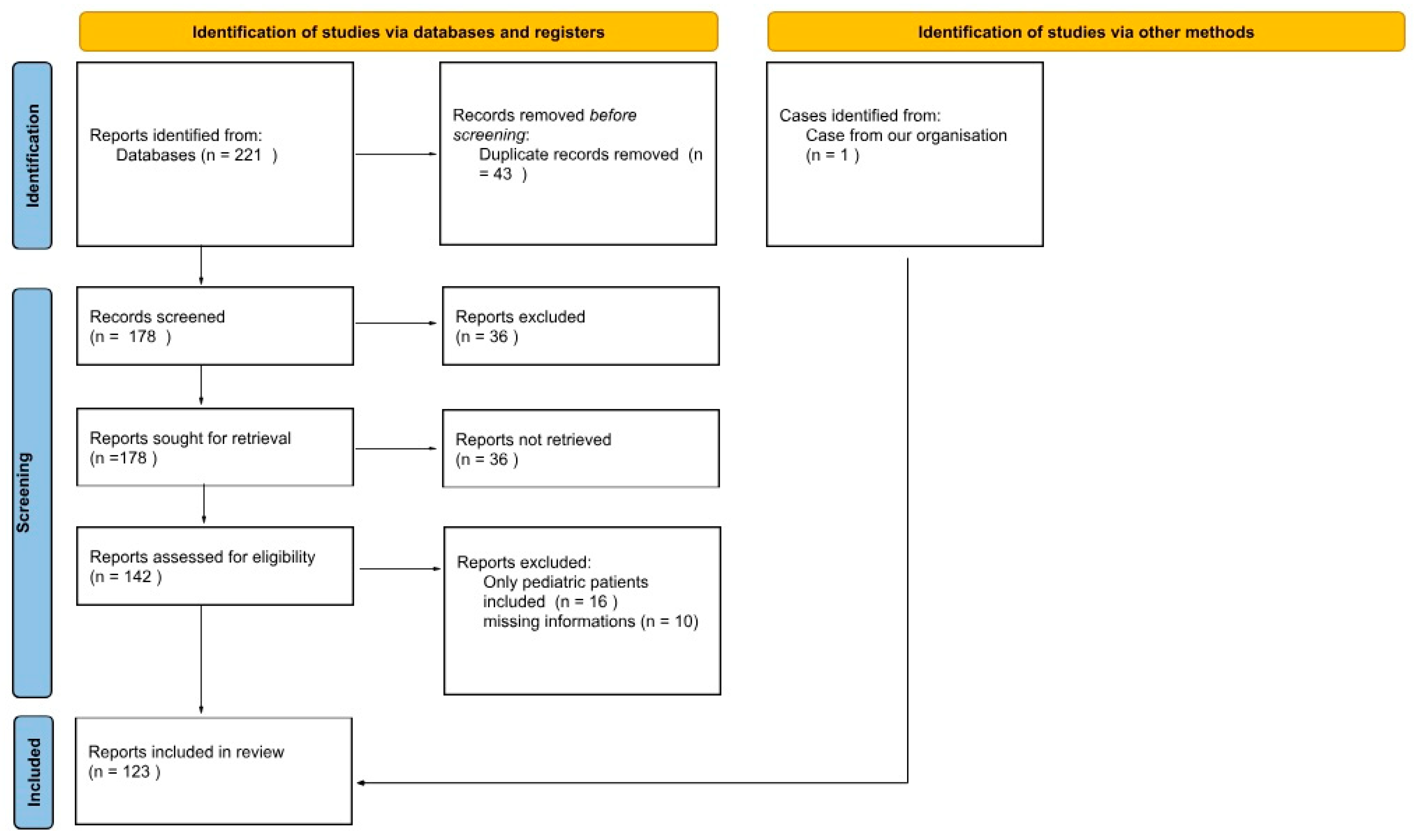

3. Materials and Methods

- Patients with a radiologically or surgically confirmed diagnosis of PPT;

- Patients aged 18 years and older;

- Complete case description, including symptoms, imaging, treatment, and outcome.

- Pediatric patients (<18 years old);

- Unavailable full-text articles;

- Articles published in languages other than English, Polish, Spanish, Chinese, or German;

- Articles that were not peer-reviewed.

4. Results

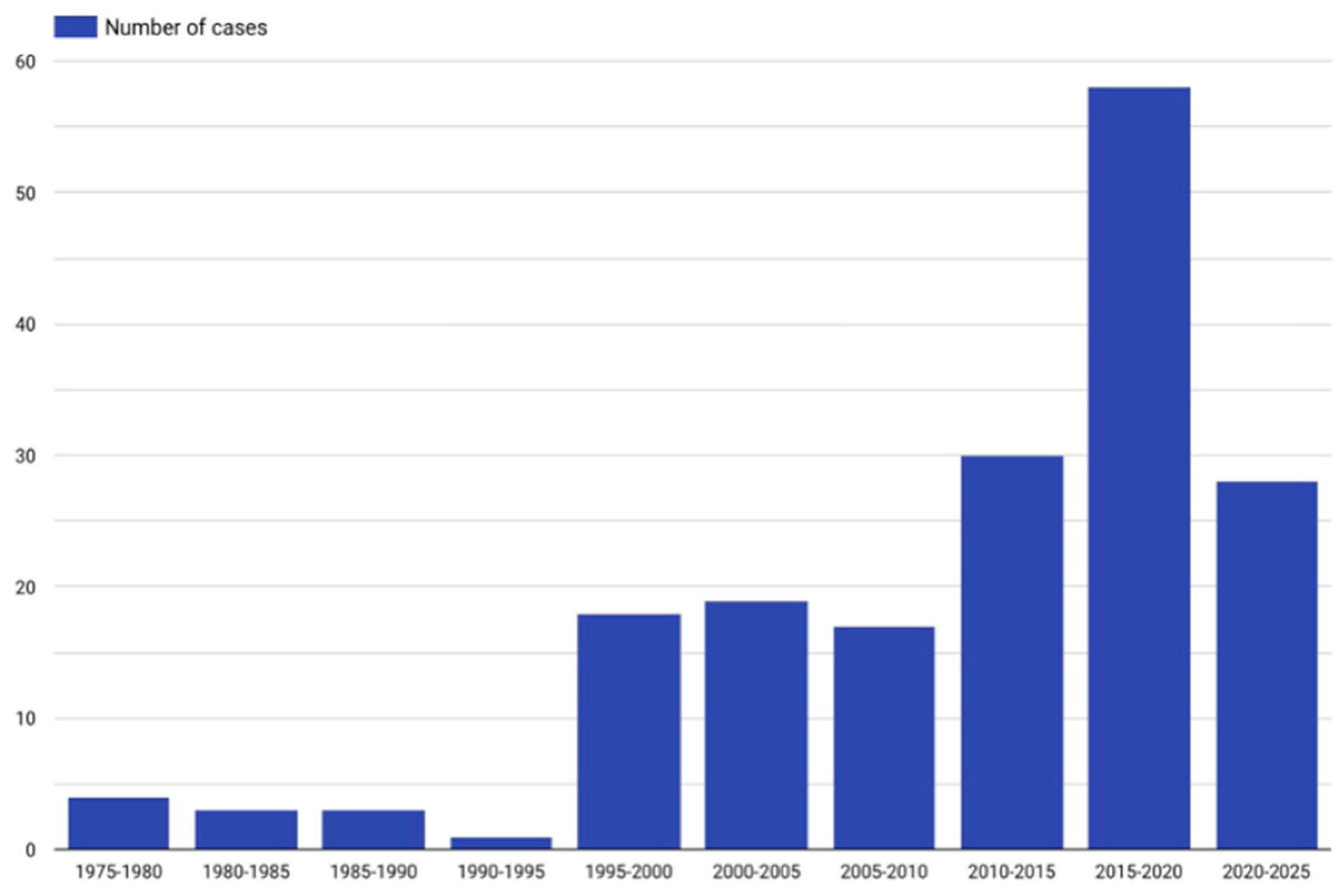

4.1. Description of the Included Studies

4.2. Results of the Meta-Analysis

4.3. Subgroup of Meta-Analysis

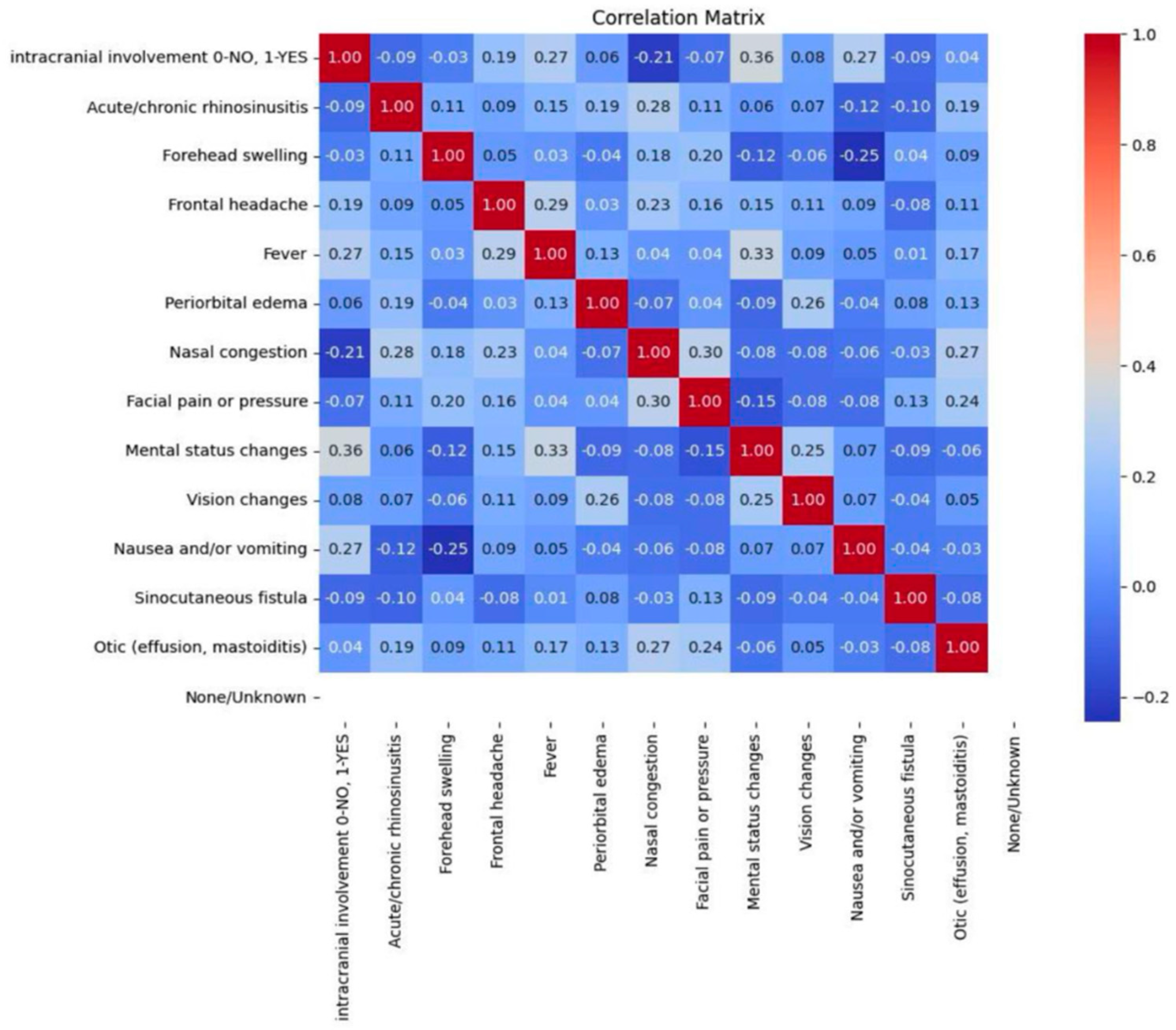

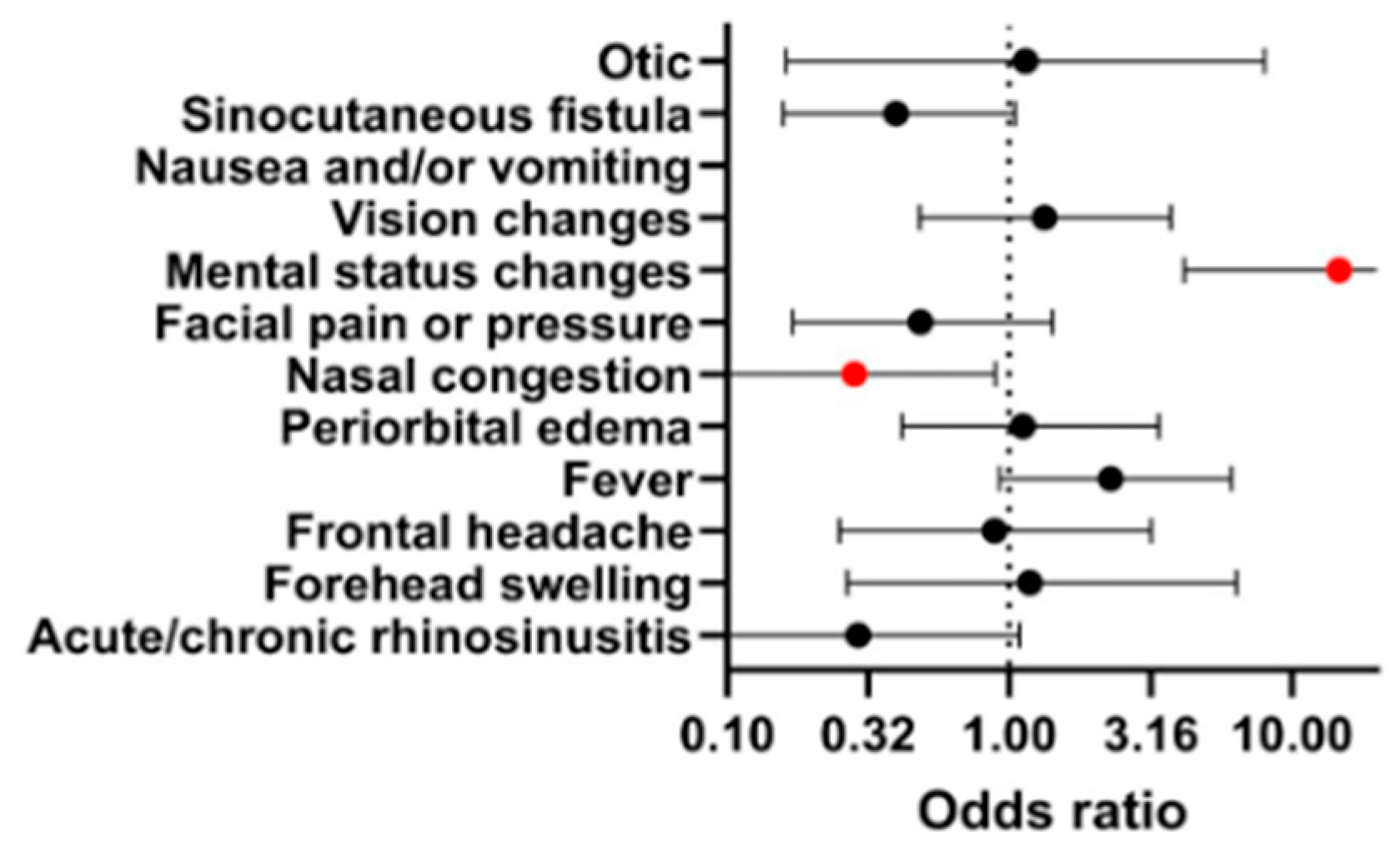

4.3.1. Signs and Symptoms

4.3.2. Medical History

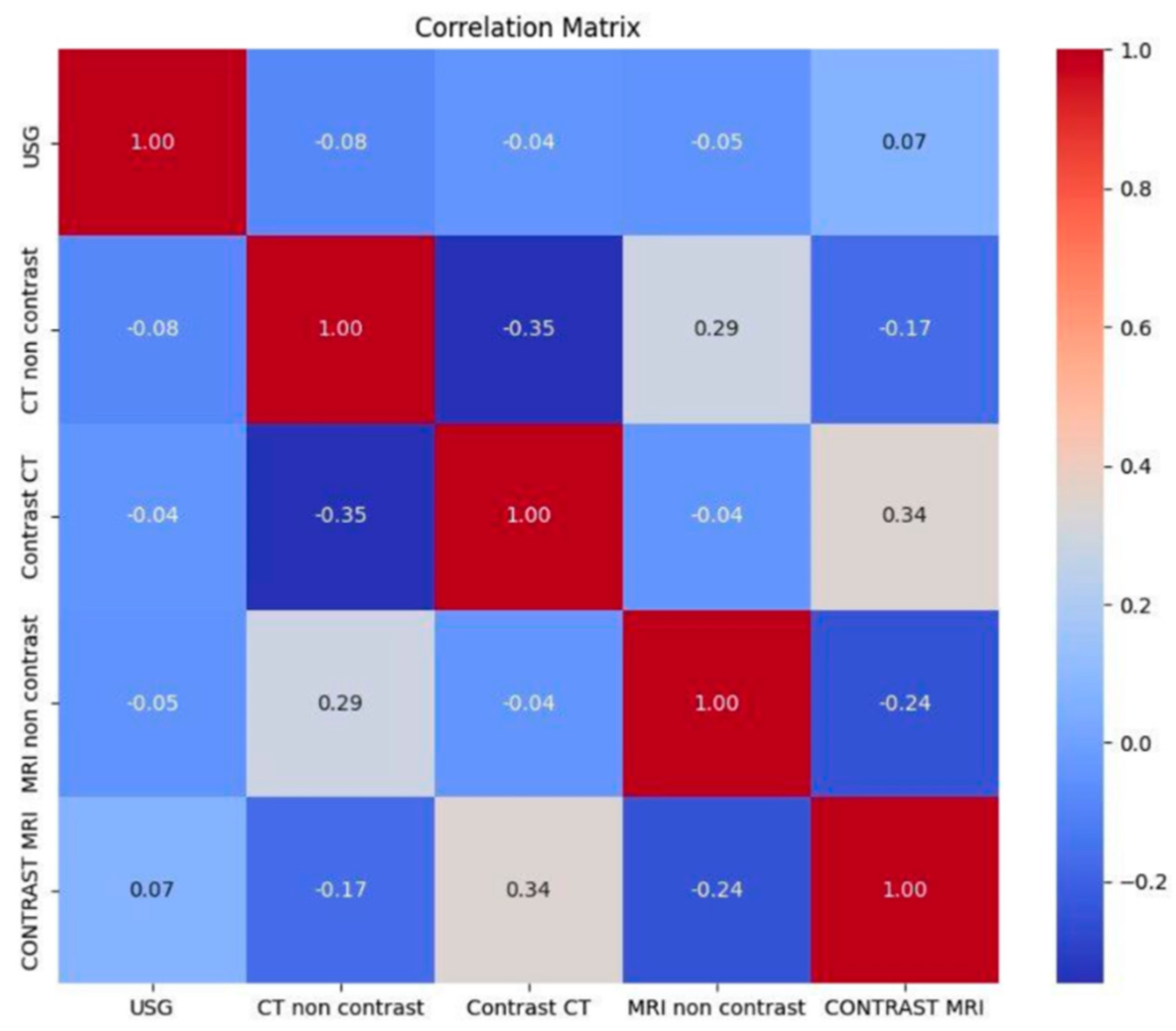

4.3.3. Radiological Imaging

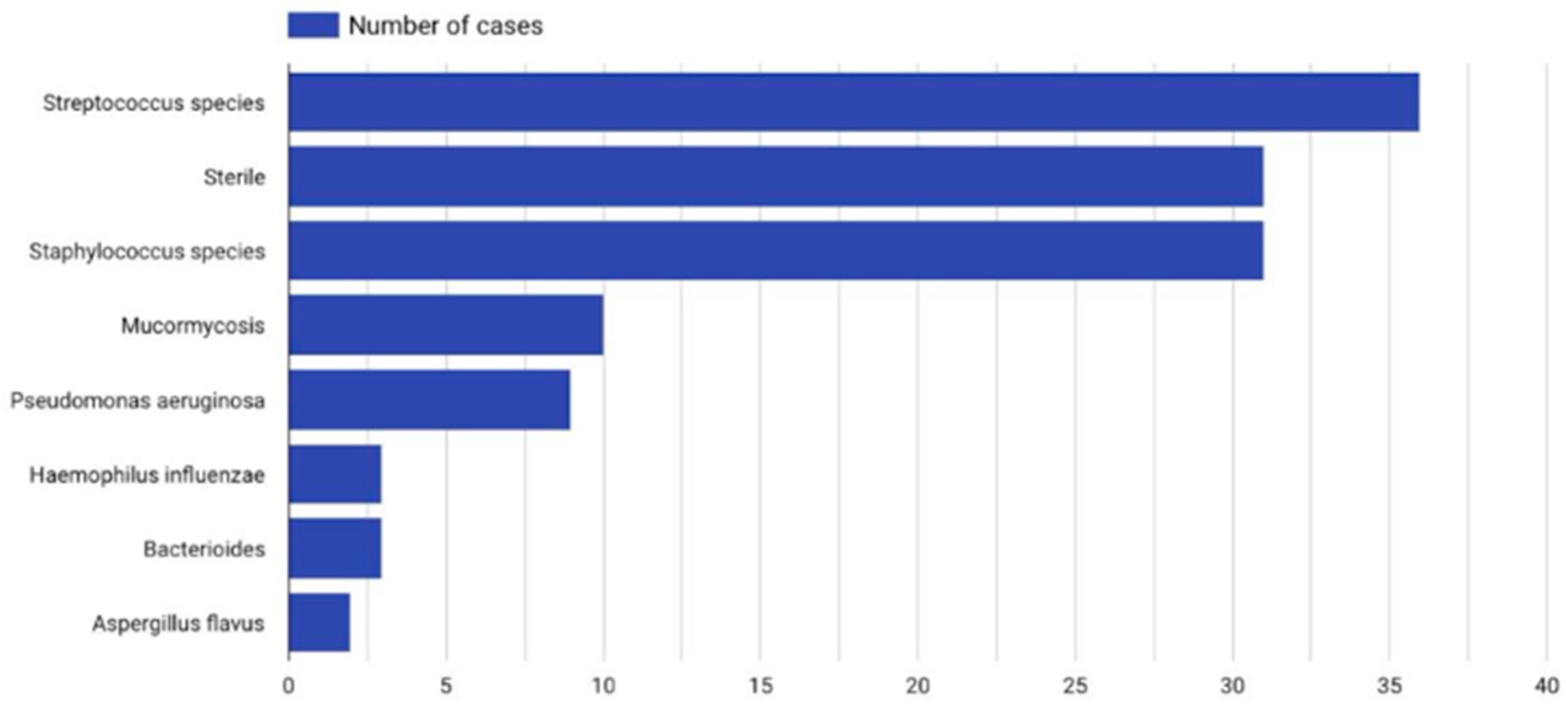

4.3.4. Microbiology and Laboratory Workup

4.3.5. Intracranial Involvement

4.3.6. Treatment Method

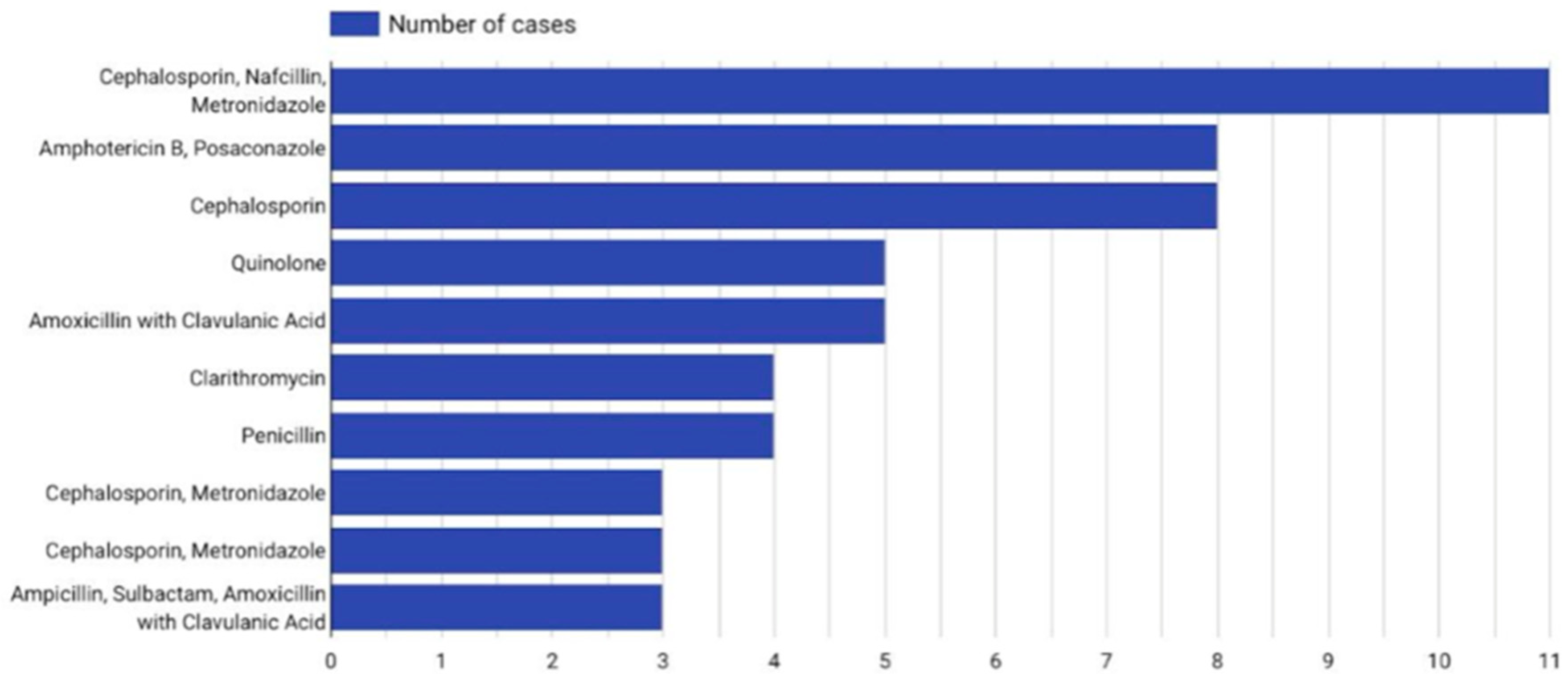

4.3.7. Antibiotic Therapy

4.3.8. Days of Hospitalization and Follow-Up

5. Discussion

5.1. Epidemiology

5.2. Pathogenesis

5.3. Signs and Symptoms

5.4. Medical History

5.5. Radiological Imaging

5.6. Microbiology and Laboratory Workup

5.7. Intracranial Involvement

5.8. Treatment Method

5.9. Antibiotic Therapy and Follow-Up

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koltsidopoulos, P.; Papageorgiou, E.; Skoulakis, C. Pott’s puffy tumor in children: A review of the literature. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, R.L.; North, L.M.; Murray, M.; Khalili, S.; Poetker, D.M. Pott’s puffy tumor: A comprehensive review of the literature. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Rhinology 2020, 58, 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, R.; Kowalski, T. Pott’s puffy tumor: A comprehensive meta-analysis of adult patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, J.P.; Linsler, S.; Nourkami-Tutdibi, N.; Meyer, S.; Becker, S.L.; Yilmaz, U.; Schick, B.; Bozzato, A.; Kulas, P. Pott’s puffy tumor: A need for interdisciplinary diagnosis and treatment. HNO 2022, 70, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketenci, I.; Unlü, Y.; Tucer, B.; Vural, A. The Pott’s puffy tumor: A dangerous sign for intracranial complications. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-laryngology 2011, 268, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Karaki, M.; Mori, N. Evaluation of adult Pott’s puffy tumor: Our five cases and 27 literature cases. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 2382–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, S.; Grulois, V.; Eloy, P.; Rombaux, P.; Bertrand, B. A Pott’s puffy tumour as a late complication of a frontal sinus reconstruction: Case report and literature review. Rhinology 2009, 47, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskin, G.A.; Kalish, S.B. Pott’s puffy tumor: A complication of intranasal cocaine abuse. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1991, 13, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, G.; Thomson, N. Pott’s puffy tumour reviewed. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1990, 104, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbon, A.; Husni, R.N.; Gordon, S.M.; Lavertu, P.; Keys, T.F. Pott’s puffy tumor due to Haemophilus influenzae: Case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellaney, G.J.; Ryan, T.J. Pott’s puffy tumour. Br. J. Dermatol. 1997, 136, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Mishriki, Y.Y. The puffy periorbital protrusion. Postgrad. Med. 1999, 105, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, B.; Todd, J.; Stucker, F.J.; Nathan, C.A. Pott’s puffy tumor and epidural abscess arising from dental sepsis: A case report. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 1732–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, R.; Tattersall, R. Pott’s puffy tumour. Lancet 2002, 359, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, S.W.; Chan, D.T.; Suen, P.Y.; Boet, R.; Poon, W.S. Pott’s puffy tumour. Hong Kong Med. J. 2002, 8, 381–382. [Google Scholar]

- Canbaz, B.; Tanriverdi, T.; Kaya, A.H.; Tüzgen, S. Pott’s puffy tumour: A rare clinical entity. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, A.; Hocwald, E.; Gross, M.; Eliashar, R. Frontal sinus cutaneous fistula: A complication of Pott’s puffy tumor. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 490–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evliyaoğlu, C.; Bademci, G.; Yucel, E.; Keskil, S. Pott’s puffy tumor of the vertex years after trauma in a diabetic patient: Case report. Neurocirugia 2005, 16, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effat, K.G.; Karam, M.; El-Kabani, A. Pott’s puffy tumour caused by mucormycosis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2005, 119, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabia, N.; Abdelkafi, M.; Bellara, I.; Khalifa, M.; Bahri, F.; Letaief, A. Pott’s puffy tumor. A case report. Med. Et Mal. Infect. 2007, 37, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Low, C.; Sastry, A.; Moriarty, B. Pott’s puffy tumor following an insect bite. J. Postgrad. Med. 2007, 53, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minutilli, E.; Pompucci, A.; Anile, C.; Corina, L.; Paludetti, G.; Magistrelli, P.; Castagneto, M. Cutaneous fistula is a rare presentation of Pott’s puffy tumour. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008, 61, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreau, K.P.; Fanciullo, L.M. Pott’s puffy tumour mimicking preseptal cellulitis. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2008, 91, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Diaz, G.J.; Hsia, R. Pott’s Puffy tumor after minor head trauma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2008, 26, 739-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannon, P.D.; McCormack, R.F. Pott’s puffy tumor and epidural abscess arising from pansinusitis. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 41, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masterson, L.; Leong, P. Pott’s puffy tumour: A forgotten complication of frontal sinus disease. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 13, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S. Recurrent Pott’s puffy tumor, a rare clinical entity. Neurol. India 2010, 58, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakos, D.; Tang, I. Image diagnosis: Pott puffy tumor. Perm. J. 2016, 20, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Smith, S.F.; Hammond-Kenny, A. Potts puffy tumour: A rare but important diagnosis. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019, 2019, rjz099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, H.C.; Park, I.H.; Lee, H.M. Endoscopic endonasal treatment of a Pott’s puffy tumor. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol 2012, 5, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peric, A.; Milojevic, M.; Ivetic, D. A Pott’s puffy tumor associated with epidural-cutaneous fistula and epidural abscess: Case report. Balk. Med. J. 2017, 34, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Muhammad, M.N.; Moallam, F.A. Pott puffy tumor: A rare complication of sinusitis. Ann. Saudi Med. 2013, 33, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, S.C. Minimally invasive surgery for Pott’s puffy tumor: Is it time for a paradigm shift in managing a 250-year-old problem? Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2017, 126, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poel, N.A.; Hansen, F.S.; Georgalas, C.; Fokkens, W.J. Minimally invasive treatment of patients with Pott’s puffy tumour with or without endocranial extension-a case series of six patients: Our experience. Clin. Otolaryngol 2016, 41, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajwani, K.M.; Desai, K.; Lew-Gor, S. Forehead swelling and frontal headache: Pott’s puffy tumour. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, 2013202737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terui, H.; Numata, I.; Takata, Y.; Ogura, M.; Aiba, S. Pott’s puffy tumor caused by chronic sinusitis resulting in sinocutaneous fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarowicz, M.; Maćkowiak, B.; Majewska, A.; Zagozda, N.; Miętkiewska-Leszniewska, D.; Wierzbicka, M. Pott’s puffy tumor in adults-cases report. Postępy W Chir. Głowy I Szyi/Adv. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 18, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi, S.; Ri, M.; Higashi, N.; Wakayama, N.; Matsune, S.; Tosa, M. Pott’s puffy tumor in an adult: A case report and review of literature. J. Nippon. Med. Sch. 2016, 83, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Paik, S.W.; Park, D.J.; Lee, E.J. Pott puffy tumor caused by dental infection: A case report and literature review. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skomro, R.; McClean, K.L. Frontal osteomyelitis (Pott’s puffy tumour) associated with Pasteurella multocida-A case report and review of the literature. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 1998, 9, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, H.J.; Kim, K.S. Odontogenic sinusitis-associated Pott’s puffy tumor: A case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022, 101, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsuki, S.; Tsuda, T.; Takeda, K.; Obata, S.; Inohara, H. A case of Pott’s puffy tumor in a patient with eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Cureus 2024, 16, 60893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Doaibel, K.; Hasan, F.; Antar, H.; Hasan, Z.; Alfeki, S. Frontal headache and swelling: A case report of Pott’s puffy tumor. Cureus 2023, 15, e50670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.P.; Manesh, A.; Regi, S.; Michael, J.S.; Kumar, R.H.; Thomas, M.; Cherian, L.M.; Varghese, L.; Kurien, R.; Moorthy, R.K.; et al. Pott’s puffy tumor: An unusual complication of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis. World Neurosurg. X 2024, 23, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, D.; Jung, S.; Chung, C.H.; Chang, Y. Pott’s puffy tumor of the upper eyelid misdiagnosed as simple abscess: A case report and literature review. Arch. Craniofacial Surg. 2024, 25, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Carcedo, L.M.; Izquierdo, J.M.; Gonzalez, M. Intracranial complications of frontal sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1984, 98, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.E. Pott’s puffy tumor: A clinical marker for osteomyelitis of the skull. Arch. Dermatol. 1985, 121, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.W.; Josephson, J.S.; Mattox, D.E.; Goldsmith, M.M.; Zinreich, S.J. Endoscopic sinus surgery for mucoceles: A viable alternative. Laryngoscope 1989, 99, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.P.; Todor, R.; Kasoff, S.S. Pott’s puffy tumor: The forgotten entity. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 84, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambakidis, N.C.; Cohen, A.R. Intracranial complications of frontal sinusitis in children: Pott’s puffy tumor revisited. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2001, 35, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağdatoğlu, C.; Güleryüz, A.; Ersöz, G.; Talas, D.Ü.; Kandemir, Ö.; Köksel, T. A rare clinical entity: Pott’s puffy tumor. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2001, 34, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabatsou, K.; Gan, Y.C.; Christie, M.; Sakas, D. Pott’s puffy tumour: A delayed complication of surgery. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2001, 15, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, E.E.; Curran, A.J.; Patil, N.; Walsh, R.M.; Rawluk, D.; Walsh, M.A. Intracranial complications of acute frontal sinusitis. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 2001, 26, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.M.; Szeto, C.C. Images from headache. Headache 2003, 43, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.K.; Schlosser, R.; Kennedy, D.W. Use of the 70-degree diamond burr in the management of complicated frontal sinus disease. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, V.N.; Raizada, R.M.; Singh, A.K.K.; Puttewar, M.P.; Bali, S. Osteomyelitis of frontal bone. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 56, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, N.; Hedlund, G.; Byington, C.L. Sinogenic intracranial empyema in children. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, N.K.; Ekambar Eshwara Reddy, C. Primary frontal sinus aspergillosis: An uncommon occurrence. Mycoses 2005, 48, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.; O’Sullivan, R.; McMahon, G. An unusual cause of headache: Pott’s puffy tumour. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, L.J.; Parkinson, J.F.; Hudson, B.J.; Brewer, J.M.; Little, N.S.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J. Headache of a diagnosis: Frontotemporal pain and inflammation associated with osteolysis. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 189, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adejumo, A.; Ogunlesi, O.; Siddiqui, A.; Sivapalan, V.; Alao, O. Pott puffy tumor complicating frontal sinusitis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 340, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, O.; Fu, B.; Sharp, H. Recurrent Pott’s puffy tumour. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr1220103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, Y.M.; Belloso, A. Pott’s puffy tumour: Harbinger of intracranial sepsis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2011, 82, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajid, T.; Kazmi, H.S.; Shah, S.A.; Ali, Z.; Khan, F.; Ghani, R.; Khan, J. Complications of nose and paranasal sinus disease. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2011, 23, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Elyassi, A.R.; Prenzel, R.; Closmann, J.J. Pott puffy tumor after maxillary tooth extraction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, H.S.; Dangayach, N.S.; Esposito, A. A tumor that is not a tumor but it sure can kill! Am. J. Case Rep. 2012, 13, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.; Kwong, F.N.; Mohammed, H.; Cathcart, R. Medical image An unusual swelling of the forehead. N. Z. Med. J. 2012, 21, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, H.; Avcu, S.; Lemmerling, M. Radiological findings in a rare case of eyelid swelling: Pott’s puffy tumor. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2012, 95, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bozdemir, K. Treatment of Pott’s Puffy tumor with balloon sinuplasty: Report of three cases. Turk. J. Ear Nose Throat 2012, 22, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shin, J.W.; Choi, I.G.; Jung, S.-N.; Kwon, H.; Shon, W.I.; Moon, S.H. Pott Puffy Tumor Appearing with a Frontocutaneous Fistula. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 23, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domville-Lewis, C.; Friedland, P.L.; Santa Maria, P.L. Pott’s puffy tumour and intracranial complications of frontal sinusitis in pregnancy. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2012, 127, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.D.; Poetker, D.M. Anterior table remodeling after treatment for Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 34, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, A.M.; Roşca, T.; Vlădescu, C.T.; Tihoan, C.; Popa, M.C.; Boer, M.C.; Cergan, R. Frontal epidural empyema (Pott’s puffy tumor) associated with Mycoplasma and depression. Rom J. Morphol. Embryol. 2014, 55 (Suppl. S3), 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.P.; Wilkie, M.D. Pott’s puffy tumour: An unforgettable complication of frontal sinusitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, brc2014204061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, S.L.; Carrie, S. Pott’s puffy tumour: A forgotten diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, bcr2015211099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H.; Jung, J.W.; Chi, M. A Patient with Pott Puffy Tumor With Pansinusitis and Orbital Involvement in an Immunocompromised Patient. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarós, P.; Ahmed, H.; Clarós, A. Post-traumatic Pott’s puffy tumour: A case report. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016, 133, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. A 60-year-old man with forehead swelling. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2016, 83, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.S. Pott’s puffy tumor. N. Z. Med. J. 2017, 130, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, R.D.; Thangaraju, P. Pott’s puffy tumor in coronavirus disease-2019 associated mucormycosis. Rev. Da Soc. Bras. De Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e0669-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salemans, R.; Bijkerk, E.; Sawor, J.; Piatkowski, A. Misdiagnosed epidermoid cyst appears Potts Puffy Tumor: A case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Reports 2022, 94, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitt, N.; Rosengren, T.; Delaney, T.; Dettmer, T. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in an Adult Female: A Case Report in a Rare Demographic. Cureus 2022, 14, e24922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.S.; Al-Smadi, A.S.; Smitt, M.; Geimadi, A.; Luqman, A.W. The rare presentation of a frontal mucocele complicated by a Pott’s puffy tumor and an epidural-cutaneous fistula: Illustrative case. J. Neurosurg. Case Lessons 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, E.W.; Bergman, Z.; Grumbine, F.L. Pott’s puffy tumour with eyelid abscess. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 58, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, H. Patient presenting with frontal subperiosteal abscess and headache: A case of Pott’s puffy tumour. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 33, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, R.; Omura, K.; Ishida, K.; Tanaka, Y. Recurrent Pott’s Puffy Tumor Treated with Anterior Skull Base Resection with Reconstruction of the Anterolateral Thigh Flap. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, e94–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusu, K.; Chandrasekharan, D.; Al Yaghchi, C.; Quiney, R. A huge Pott’s puffy tumour secondary to pansinusitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e229755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.J.; Kim, K.S. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019, 99, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendolino, A.L.; Koumpa, F.S.; Zhang, H.; Leong, S.C.; Andrews, P.J. Draf III frontal sinus surgery for the treatment of Pott’s puffy tumour in adults: Our case series and a review of frontal sinus anatomy risk factors. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2020, 277, 2271–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paw, E.; Ong, C.T.W.; Vangaveti, V. Pott’s puffy tumour in an immunosuppressed adult: Case report and systematic review of literature. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, rjaa528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, H.; Min, Z.; Como, J.; Bhanot, N. Pott’s puffy tumor caused by Actinomyces naeslundii. IDCases 2020, 22, e00974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.W.; Montovano, M.; Kubiak, A.; Khalid, S.; Ellner, J. Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Intracranial Extension Not Requiring Neurosurgical Intervention. Cureus 2020, 12, e10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideris, G.; Delides, A.; Proikas, K.; Papadimitriou, N. Pott Puffy Tumor in Adults: The Τiming of Surgical Ιntervention. Cureus 2020, 12, e11781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansini, A.; Copelli, C.; Manfuso, A.; d’Ecclesia, A.; Califano, L.; Cocchi, R. Pott’s Puffy Tumor and Intranasal Cocaine Abuse. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2020, 31, e418–e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Wakayama, N.; Hamajima, Y.; Miyata, K.; Takahashi, H.; Kobayakawa, S. A Rare Case of Palpebral Cellulitis, a Variation of Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2020, 11, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birks, S.; Peart, L. Pott’s Puffy Tumour: A rare but sinister cause of facial swelling. Acute Med. J. 2021, 20, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.; Chao, J.; Pearce, Z.D. Progressive Eyelid Swelling in a Middle-aged Man. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 139, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.M.; Tilak, A.M.; Miller, P.L.; Grayson, J.W.; Cho, D.-Y.; Woodworth, B.A. Treatment of Frontal Sinus Osteomyelitis in the Age of Endoscopy. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 35, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, J.; Shockey, D.; Adhikari, S. The Use of Point-of-care Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Pott’s Puffy Tumor: A Case Report. Clin. Pract. Cases Emerg. Med. 2021, 5, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Min, H.J. A tool for the psychophysical assessment of olfactory dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Ear Nose Throat J. 2024, 103, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.A.; Hussain, A.; Gill, H.S.; Monteiro, E.; Liu, E.S. Pott’s puffy tumour presenting as a necrotic eyelid lesion. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 52, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, P.; Chundury, R.; Perry, J.D. Pott’s Puffy Tumor: A Rare Presentation. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 33, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, F.; Bonardi, S.; Modoni, A. When the diagnosis is written on the forehead. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 47, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyton, T.; Henderson, A.; Morris, J.; McDonald, S. Acase of Pott’s puffy tumour from primary dental infection. Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr-2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.S.; Wilkins, S.E. Pott Puffy Tumor. J. Osteopath. Med. 2018, 118, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, A.; Passaplan, C.; Rusconi, A.; Colin, V.; Erard, V.; Stauffer, E.; Otten, P. Pott’s puffy tumor presenting as a frontal swelling under a Swiss army helmet. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 173, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, S.P.; Ilkanich, P.; Congeni, B. Complicated Fusobacterium Sinusitis: A Case Report. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettias, B.; Dow, G.; Srinivasan, D.; Ramakrishnan, Y. Pott’s puffy tumour: Innovative technique in calvarial reconstruction. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2019, 133, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, K.M.; Gnawali, G.P.; Gc, R. Frontal bone osteomyelitis in adult. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2022, 20, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salom-Covenas, C.; Benito-Navarro, J.R.; Gutierrez-Gallardo, A.; Porras-Alonso, E. Tumor inflamatorio de Pott: Descripción de un caso. Rev. ORL 2022, 5, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmler, D.; Boles, R. Intracranial complications of frontal sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1980, 90, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, R.M.; Gross, C.W.; Phillips, C.D. Suppurative intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1998, 108, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado Pellejero, J.; Lorente Muñoz, A.; Elenwoke, N.; Cortés Franco, S. Pott’s puffy tumor by Actinomyces after minor head trauma. Neurocirugía 2018, 30, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acke, F.; Lemmerling, M.; Heylbroeck, P.; De Vos, G.; Verstraete, K. Pott’s puffy tumor: CT and MRI findings. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2011, 94, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, E.; Vaddi, A.; Rengasamy, K.; Tadinada, A. Pott’s puffy tumor, a forgotten complication of sinusitis: Report of two cases. Cureus 2023, 15, 33452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, K.; Branch, J.; Hasegawa, K. Images in emergency medicine. Facial swelling. Pott’s puffy tumor with subdural Empyema 2012, 59, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Stienen, M.N.; Hermann, C.; Breuer, T.; Gautschi, O.P. Pott’s puffy tumor-severe course of a sinusitis. Praxis 2010, 99, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Deng, H.H. One case of Pott’s puffy tumor: Inverted papilloma of nasal sinus postoperative complications. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi. J. Clin. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 32, 304–305. [Google Scholar]

- Banooni, P.; Rickman, L.S.; Ward, D.M. Pott puffy tumor associated with intranasal methamphetamine. JAMA 2000, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.N.; Nel, J.R. Acute spreading osteomyelitis of the skull complicating frontal sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1977, 91, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivdas, S.; Philips, A.B. Presentation of Pott’s Puffy Tumour in a 71-Year-Old Man with Atypical History. OALib J. 2022, 9, 1108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, J.I.; De Jesus, O. Pott puffy tumor. In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, N.; Kochar, P.; Kumar, Y. Pott puffy tumor. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2017, 30, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, R.; Schweintzger, G.; Uggowitzer, M.; Urban, C.; Stammberger, H.; Eder, H. Recurrent Pott’s puffy tumor—Atypical presentation of a rare disorder. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2009, 121, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokot, K.; Fercho, J.M.; Duszyński, K.; Jagieło, W.; Miller, J.; Chasles, O.G.; Yuser, R.; Klecha, M.; Matuszczak, R.; Nowiński, E.; et al. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124062

Kokot K, Fercho JM, Duszyński K, Jagieło W, Miller J, Chasles OG, Yuser R, Klecha M, Matuszczak R, Nowiński E, et al. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokot, Klaudia, Justyna Małgorzata Fercho, Konrad Duszyński, Weronika Jagieło, Jakub Miller, Oskar Gerald Chasles, Rami Yuser, Martyna Klecha, Rafał Matuszczak, Eryk Nowiński, and et al. 2025. "Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124062

APA StyleKokot, K., Fercho, J. M., Duszyński, K., Jagieło, W., Miller, J., Chasles, O. G., Yuser, R., Klecha, M., Matuszczak, R., Nowiński, E., Klein-Awerjanow, K., Nowicki, T., Mielczarek, M., Szypenbejl, J., Siemiński, M., & Szmuda, T. (2025). Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124062