Disease Acceptance and Stress as Factors Explaining Preoperative Anxiety and the Need for Information in Patients Undergoing Operative Minihysteroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Operative Minihysteroscopy

3.3. Psychological Varialbles

3.3.1. Psychological Variables—Does Preoperative Anxiety Depend on Previous Surgeries and Current Diagnosis?

3.3.2. Psychological Variables—Does the Need for Information in the Preoperative Phase Depend on Previous Surgeries and Current Diagnosis?

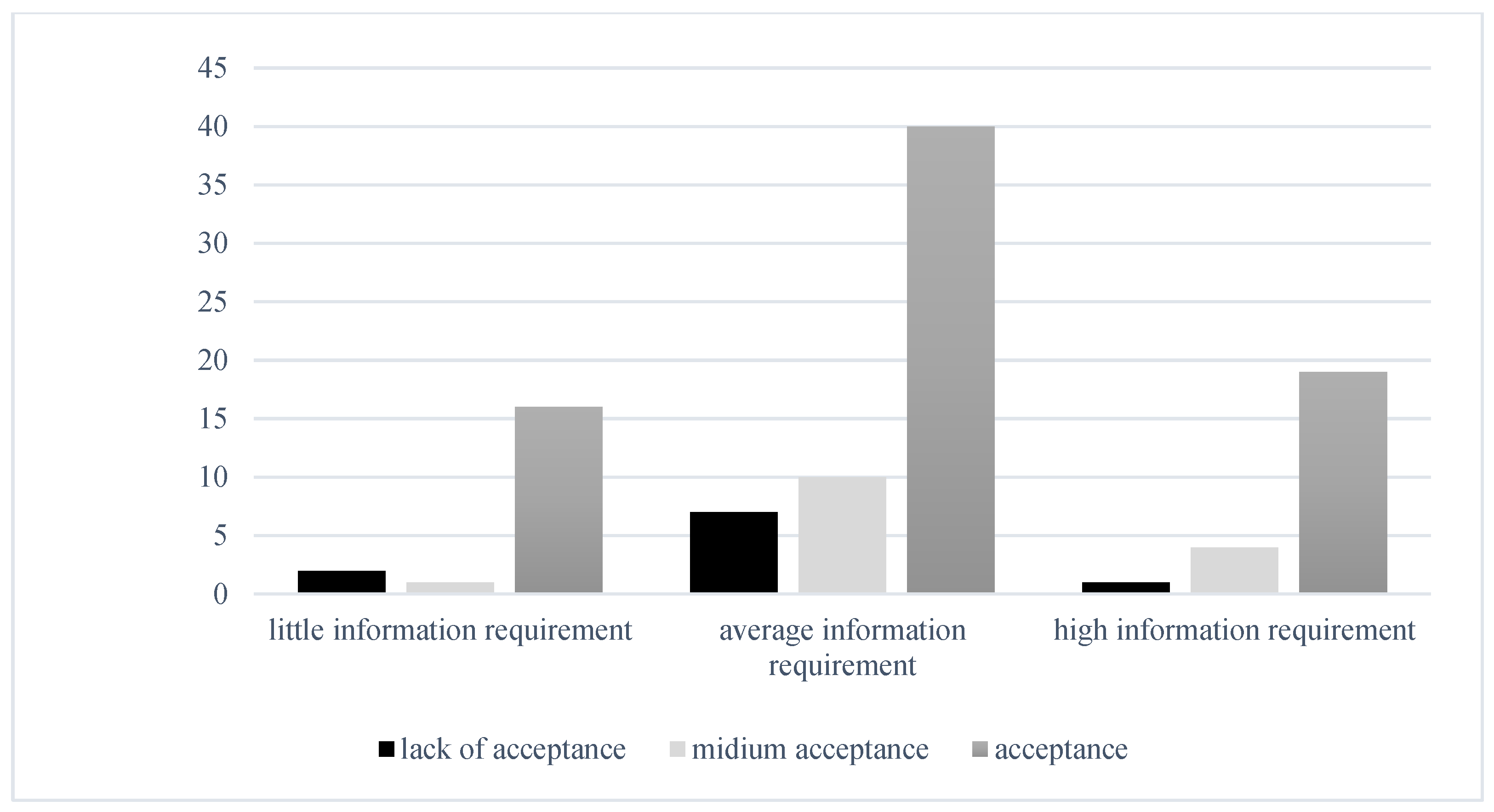

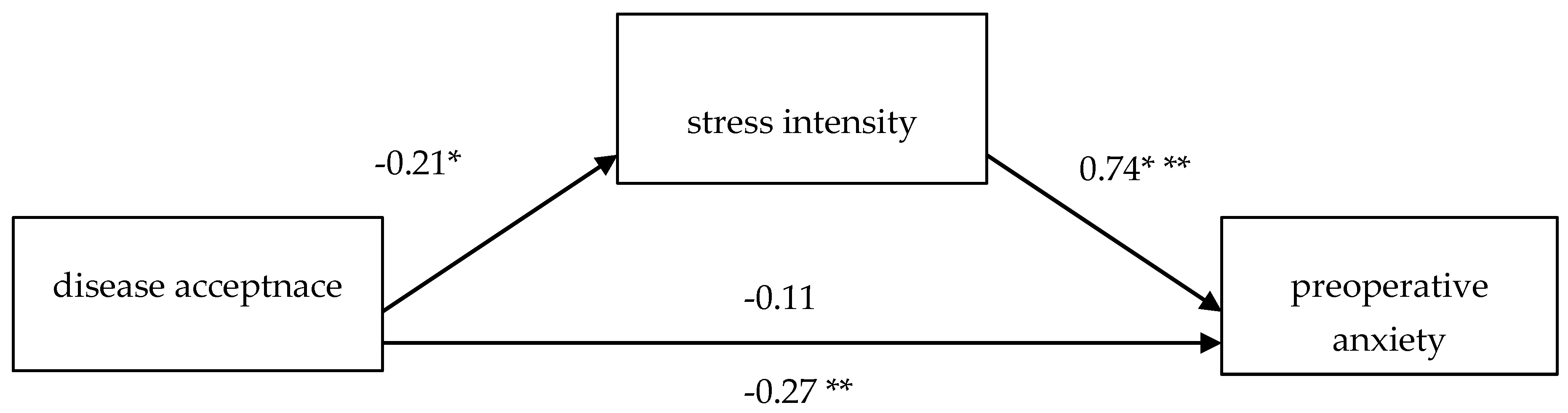

3.4. Correlation of Psychological Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salazar, C.A.; Isaacson, K.B. Office Operative Hysteroscopy: An Update. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, R.; Santangelo, F.; Gordts, S.; Di Cesare, C.; Van Kerrebroeck, H.; De Angelis, M.C.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A. Outpatient hysteroscopy. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 2018, 10, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kremer, C.; Duffy, S.; Moroney, M. Patient satisfaction with outpatient hysteroscopy versus day case hysteroscopy: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2000, 320, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, F.A.; Rogerson, L.J.; Duffy, S.R. A randomised controlled trial comparing outpatient versus daycase endometrial polypectomy. BJOG 2006, 113, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, R.; Lanzone, A.; Tagliaferri, V.; Di Florio, C.; Ricciardi, L.; Selvaggi, L.; Guido, M. Using a 16-French Resectoscope as an Alternative Device in the Treatment of Uterine Lesions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dealberti, D.; Riboni, F.; Prigione, S.; Pisani, C.; Rovetta, E.; Montella, F.; Garuti, G. New mini-resectoscope: Analysis of preliminary quality results in outpatient hysteroscopic polypectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 288, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, E.; Parisi, C.; Galantino, P.; Pinto, V.; Barba, B.; Schonauer, S. Reliability, feasibility, and safety of minihysteroscopy with a vaginoscopic approach: Experience with 6000 cases. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Vollenhoven, B. Pain Control in Outpatient Hysteroscopy. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2002, 57, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finikiotis, G. Side-Effects and Complications of Outpatient Hysteroscopy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1993, 33, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluchino, N.; Ninni, F.; Angioni, S.; Artini, P.; Araujo, V.G.; Massimetti, G.; Genazzani, A.; Cela, V. Office Vaginoscopic Hysteroscopy in Infertile Women: Effects of Gynecologist Experience, Instrument Size, and Distention Medium on Patient Discomfort. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemma, G.; Schiattarella, A.; Colacurci, N.; Vitale, S.G.; Cianci, S.; Cianci, A.; De Franciscis, P. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain relief for office hysteroscopy: An up-to-date review. Climacteric 2020, 23, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, M.A.; Cohen, J.L.; Borszcz, G.S.; Cano, A.; Radcliffe, A.M.; Porter, L.S.; Schubiner, H.; Keefe, F.J. Pain and emotion: A biopsychosocial review of recent research. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 942–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogedegbe, G.; Pickering, T.G.; Clemow, L.; Chaplin, W.; Spruill, T.M.; Albanese, G.M.; Eguchi, K.; Burg, M.; Gerin, W. The misdiagnosis of hypertension: The role of patient anxiety. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 2459–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Wszołek, K.; Nowak, A.; Ignaszak-Kaus, N.; Muszyńska, M.; Wilczak, M. Evaluation of Stress Hormone Levels, Preoperative Anxiety, and Information Needs before and after Hysteroscopy under Local Anesthesia in Relation to Transvaginal Procedures under General, Short-Term Anesthesia. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 49, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, F.; Edipoglu, I.S. Evaluation of preoperative anxiety and fear of anesthesia using APAIS score. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2018, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Li, S.; Zhong, Z.; Luo, Q.; Nie, C.; Hu, D.; Li, Y. The Effect of Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream Combined with or Without Remimazolam on VAS and APAIS Anxiety Score in Patient Undergoing Spinal Anesthesia. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 3429–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürler, H.; Yılmaz, M.; Türk, K.E. Preoperative Anxiety Levels in Surgical Patients: A Comparison of Three Different Scale Scores. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2022, 37, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemła, A.J.; Nowicka-Sauer, K.; Jarmoszewicz, K.; Wera, K.; Batkiewicz, S.; Pietrzykowska, M. Measures of preoperative anxiety. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2019, 51, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boker, A.; Brownell, L.; Donen, N. The Amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale provides a simple and reliable measure of preoperative anxiety. Can. J. Anaesth. 2002, 49, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Sang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, K.; Bo, L. Personality, Preoperative Anxiety, and Postoperative Outcomes: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellstadius, Y.; Lagergren, J.; Zylstra, J.; Gossage, J.; Davies, A.; Hultman, C.M.; Lagergren, P.; Wikman, A. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among esophageal cancer patients prior to surgery. Dis. Esophagus 2017, 30, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado-Olivares, J.; Chover-Sierra, E. Preoperatory Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Diseases 2019, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, M.S.; Hakami, O.A.O.; Al-Amri, A.M. Assessment of Preoperative Anxiety among Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2017, 69, 2329–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.; Ismail, S. Preoperative anxiety in patients selecting either general or regional anesthesia for elective cesarean section. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 31, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, M.; Mushtaq, A.; Mukhtar, S.; Khan, Z. Preoperative anxiety before elective surgery. Neurosciences 2007, 12, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Lach, A.; Malinger, A. Evaluation of pain during hysteroscopy under local anesthesia, including the stages of the procedure. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambadauro, P.; Navaratnarajah, R.; Carli, V. Anxiety at outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol. Surg. 2015, 12, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Demler, O.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, R.V.; Fisher, E.A.; de la Vega, R.; Lumley, M.A.; Palermo, T.M. Alexithymia in individuals with chronic pain and its relation to pain intensity, physical interference, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2019, 160, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Jasielska, A.; Wszołek, K.; Tomczyk, K.; Lach, A.; Mruczyński, A.; Niegłos, M.; Wilczyńska, A.; Bednarek, K.; Wilczak, M. Pain Severity During Hysteroscopy by GUBBINI System in Local Anesthesia: Covariance Analysis of Treatment and Effects, Including Patient Emotional State. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Ortiz, M.; Espinosa Ruiz, A.; Martínez Delgado, C.; Barrena Sánchez, P.; Salido Valle, J.A. Do preoperative anxiety and depression influence the outcome of knee arthroplasty? Reumatol. Clin. 2020, 16, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozieł, P.; Lomper, K.; Uchmanowicz, B.; Polański, J. Związek akceptacji choroby oraz lęku i depresji z oceną jakości życia pacjentek z chorobą nowotworową gruczołu piersiowego. Med. Paliatywna W Praktyce 2016, 10, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dryhinicz, M.; Rzepa, T. The Level of Anxiety, Acceptance of Disease and Strategy of Coping with Stress in Patients Oncological and Non-oncological. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska. Sect. J. Paedagog. Psychol. 2018, 31, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Saviola, F.; Pappaianni, E.; Monti, A.; Grecucci, A.; Jovicich, J.; De Pisapia, N. Trait and state anxiety are mapped differently in the human brain. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.J.; Vytal, K.; Cornwell, B.R.; Grillon, C. The impact of anxiety upon cognition: Perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. Conceptual and methodological issues in research on anxiety. In Anxiety: Current Trends in Theory and Research on Anxiety; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Vagg, P.R.; Spielberger, C.D.; O’Hearn, T.P. Is the state-trait anxiety inventory multidimensional? Pers. Individ. Differ. 1980, 1, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Walden-Gałuszko, K.; Majkowicz, M. Jakość Życia w Chorobie Nowotworowej: Praca Zbiorowa; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego: Gdańsk, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Gianaros, P.J.; Manuck, S.B. A Stage Model of Stress and Disease. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Vagg, P.R. Test Anxiety: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Altun, D.; Oguz, B.H.; Ilhan, M.; Demircan, F.; Koltka, K. The effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparoscopic chole-cystectomy. J. Anesth. 2014, 28, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibabu, A.; Ketema, T.; Beyene, M.; Belachew, D.; Abocherugn, H.; Mohammed, A. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among women admitted for elective obstetric and gynecologic surgery in public hospitals, Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łepecka-Klusek, C.; Pilewska-Kozak, A.B.; Syty, K.; Tkaczuk-Włach, J.; Szmigielska, A.; Jakiel, G. Oczekiwanie na planowaną operację ginekologiczną w ocenie kobiet. Ginekol. Pol. 2009, 80, 699–703. [Google Scholar]

- Motyka, M. Obawy pacjentów przygotowywanych do zabiegu operacyjnego. Szt. Leczenia 2001, 4, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pilewska, A.; Jakiel, G. Oczekiwanie na interwencję chirurgiczną jako sytuacja trudna dla kobiet. Przegląd Menopauzalny 2005, 5, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ziębicka, J.; Gajdosz, R.; Brombosz, A. Wybrane aspekty lęku u chorych oczekujących na operację. Anestezjol. Intensywna Ter. 2006, 1, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pielog, J.; Płotek, W.; Cybulski, M. Wybrane procesy emocjonalne w okresie okołooperacyjnym—Przegląd zjawisk. Anestezjol. I Ratownictwo 2014, 8, 206–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, M. An evolutionary perspective on anxiety. In Anxiety as Symptom and Signal; Roose, W.S., Click, S.R., Eds.; Analytic Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | n = 116 | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21–30 years | 16 | 13.8% |

| 31–40 years | 46 | 39.7% | |

| 41–50 years | 36 | 31.0% | |

| 51–60 years | 12 | 10.3% | |

| >61 years | 6 | 5.2% | |

| Marital status | Single | 24 | 20.7% |

| Married | 80 | 69.0% | |

| Widowed | 3 | 2.6% | |

| Divorced | 9 | 7.8% | |

| Education | Primary | 1 | 0.9% |

| Vocational | 7 | 6.0% | |

| Secondary | 31 | 26.7% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 | 11.2% | |

| Higher | 64 | 55.2% | |

| Occupational status | Retirement | 5 | 4.3% |

| Unemploed | 5 | 4.3% | |

| Manual worker | 26 | 22.4% | |

| White-collar worker | 80 | 69.0% | |

| Place of residence | Village <2000 citizens | 43 | 37.1% |

| City 2000–50,000 citizens | 20 | 17.2% | |

| City 50,000–200,000 citizens | 10 | 8.6% | |

| City 200,000–500,000 citizens | 5 | 4.3% | |

| City > 500,000 citizens | 38 | 32.8% | |

| Previous gynecological surgeries | Cesarean section | 12 | 10.3% |

| Surgeries other than gynecological | 34 | 29.3% | |

| Minor gynecological procedure (abrasio/hysteroscopy) | 18 | 15.5% | |

| Moderate gynecological procedure | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Major gynecological surgery | 6 | 5.2% | |

| No | 45 | 38.8% | |

| Natural childbirth * | 0 | 51 | 44.0% |

| 1 | 22 | 19.0% | |

| 2 | 35 | 30.2% | |

| 3 and more | 8 | 7% |

| n | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | Other | 55 | 47.4% |

| Other, depression | 7 | 6.0% | |

| Other, depression, neurosis | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Other, migraine | 3 | 2.6% | |

| Other, anxiety disorders | 4 | 3.4% | |

| Migraine | 2 | 1.7% | |

| Migraine, depression | 3 | 2.6% | |

| Depression | 2 | 1.7% | |

| No | 39 | 33.6% |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Polyp | 90 | 77.6% |

| Hypertrophy/abnormal bleeding | 12 | 10.3% | |

| Myomas | 14 | 12.1% | |

| Procedure | Operative hysteroscopy; endometrial polyp resection | 94 | 80% |

| Operative hysteroscopy; uterine myoma resection | 8 | 6.9% | |

| Operative hysteroscopy; polypoid endometrial and hyperplasia resection | 14 | 12.1% |

| Variable | M | SD | Min. | Max. | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.121 | 9.885 | 21 | 68 | 0.966 | 0.005 |

| Weight [kg] | 71.940 | 17.009 | 48 | 138 | 0.903 | <0.001 |

| Height [cm] | 166.569 | 6.356 | 152 | 178 | 0.978 | 0.050 |

| BMI | 25.829 | 5.829 | 17.4 | 44.5 | 0.904 | <0.001 |

| Miscarriages | 0.147 | 0.442 | 0 | 3 | 0.370 | <0.001 |

| Births | 1.198 | 1.217 | 0 | 9 | 0.748 | <0.001 |

| Lesion size during ultrasound [mm] | 12.000 | 5.099 | 4 | 25 | 0.932 | <0.001 |

| Procedure time [min] | 18.103 | 6.520 | 10.0 | 35.0 | 0.874 | <0.001 |

| M | SD | Min. | Max. | W | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) | 32.46 | 8.94 | 8.00 | 40.0 | 0.798 | <0.001 |

| Stress (VAS) | 4.37 | 2.20 | 0 | 10 | 0.962 | 0.002 |

| APAIS: Anxiety Scale | 9.34 | 3.56 | 4.00 | 20.0 | 0.925 | <0.001 |

| APAIS: Need-for-Information Scale | 6.22 | 1.85 | 2.00 | 10.0 | 0.961 | 0.002 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) | - | |||

| 2. Stress (VAS) | −0.248 * | - | ||

| 3. APAIS: Anxiety Scale | −0.315 ** | 0.746 ** | ||

| 4. APAIS: Need-for-Information Scale | −0.113 | 0.251 * | 0.367 ** | - |

| Diagnosis | KW (df = 2) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyp (n = 90) M (SD) | Myomas (n = 12) M (SD) | Endometrial Hyperplasia/Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (n = 14) M (SD) | |||

| Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) | 32.22 (9.26) | 34.08 (7.55) | 32.57 (8.27) | 0.152 | 0.927 |

| Stress (VAS) | 4.56 (2.13) | 3.92 (2.23) | 3.57 (2.53) | 4.202 | 0.122 |

| APAIS: Anxiety Scale | 14.79 (5.87) | 9.25 (2.96) | 9.25 (2.96) | 1.334 | 0.513 |

| APAIS: Need-for-Information Scale | 6.36 (1.87) | 5.67 (1.83) | 5.86 (1.75) | 1.801 | 0.406 |

| Previous Surgeries | KW (df = 1) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 45) M (SD) | Yes (n = 71) M (SD) | |||||

| Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) | 34.58 (8.08) | 31.11 (9.25) | 5.83231 | 0.016 ε2 = 0.05072 | ||

| Stress (VAS) | 4.49 (2.46) | 4.30 (2.03) | 0.16347 | 0.686 | ||

| APAIS: Anxiety Scale | 9.31 (3.87) | 9.37 (3.37) | 0.15930 | 0.690 | ||

| APAIS: Need-for-Information Scale | 6.20 (1.95) | 6.24 (1.80) | 0.00119 | 0.972 | ||

| Other (n = 35) M (SD) | Gynecolo-gical (n = 24) M (SD) | Cesarean section (n = 12) M (SD) | (df = 3) | |||

| Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) | 34.58 (8.08) | 32.06 (8.38) | 30.63 (9.50) | 29.33 (11.47) | 6.22 | 0.101 |

| Stress (VAS) | 4.49 (2.46) | 3.74 (1.93) | 4.58 (2.04) | 5.33 (1.92) | 7.22 | 0.065 |

| APAIS: Anxiety Scale | 9.31 (3.87) | 8.77 (3.44) | 9.38 (2.73) | 11.08 (3.99) | 5.14 | 0.162 |

| APAIS: Need-for-Information Scale | 6.20 (1.95) | 6.40 (1.91) | 5.96 (1.49) | 6.33 (2.10) | 1.75 | 0.626 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Jasielska, A.; Wszołek, K.; Lach, A.; Stankowska-Mazur, I.; Tomczyk, K.; Mruczyński, A.; Niegłos, M.; Wilczyńska, A.; Bednarek, K.; et al. Disease Acceptance and Stress as Factors Explaining Preoperative Anxiety and the Need for Information in Patients Undergoing Operative Minihysteroscopy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113659

Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Jasielska A, Wszołek K, Lach A, Stankowska-Mazur I, Tomczyk K, Mruczyński A, Niegłos M, Wilczyńska A, Bednarek K, et al. Disease Acceptance and Stress as Factors Explaining Preoperative Anxiety and the Need for Information in Patients Undergoing Operative Minihysteroscopy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113659

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmaj-Wierzchowska, Karolina, Aleksandra Jasielska, Katarzyna Wszołek, Agnieszka Lach, Izabela Stankowska-Mazur, Katarzyna Tomczyk, Adrian Mruczyński, Martyna Niegłos, Aleksandra Wilczyńska, Kinga Bednarek, and et al. 2025. "Disease Acceptance and Stress as Factors Explaining Preoperative Anxiety and the Need for Information in Patients Undergoing Operative Minihysteroscopy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113659

APA StyleChmaj-Wierzchowska, K., Jasielska, A., Wszołek, K., Lach, A., Stankowska-Mazur, I., Tomczyk, K., Mruczyński, A., Niegłos, M., Wilczyńska, A., Bednarek, K., Wierzchowski, M., & Wilczak, M. (2025). Disease Acceptance and Stress as Factors Explaining Preoperative Anxiety and the Need for Information in Patients Undergoing Operative Minihysteroscopy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113659