The Effect of Ovarian Endometriosis on Pregnancy Outcomes in Spontaneous Pregnancies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted reproductive techniques |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| PPROM | Preterm premature rupture of membranes |

| ICP | Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

| FGR | Fetal growth restriction |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symons, L.K.; Miller, J.E.; Kay, V.R.; Marks, R.M.; Liblik, K.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. The Immunopathophysiology of Endometriosis. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafah, M.; Rashid, S.; Akhtar, M. Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2021, 28, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Adur, M.; Kannan, A.; Davila, J.; Zhao, Y.; Nowak, R.; Bagchi, M.; Bagchi, I.; Li, Q. Progesterone Alleviates Endometriosis via Inhibition of Uterine Cell Proliferation, Inflammation and Angiogenesis in an Immunocompetent Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 165347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farland, L.V.; Prescott, J.; Sasamoto, N.; Tobias, D.K.; Gaskins, A.J.; Stuart, J.J.; Carusi, D.A.; Chavarro, J.E.; Horne, A.W.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; et al. Endometriosis and Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kawahara, N.; Ogawa, K.; Yoshimoto, C. A Relationship Between Endometriosis and Obstetric Complications. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallvé-Juanico, J.; Houshdaran, S.; Giudice, L.C. The endometrial immune environment of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 564–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirtea, P.; Cicinelli, E.; Nola, R.D.; Ziegler, D.D.; Ayoubi, J. Endometrial causes of recurrent pregnancy losses: Endometriosis, adenomyosis, and chronic endometritis. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, Y.; Matsuzaki, S.; Ueda, Y.; Kakuda, M.; Kakuda, S.; Sakaguchi, H.; Maeda, M.; Hisa, T.; Kamiura, S. Association between Endometriosis and Delivery Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.; Sterrenburg, M.; Lane, S.; Maheshwari, A.; Li, T.C.; Cheong, Y. Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 592–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, S.; Choudhry, A.J.; Firth, B.; Bacal, V.; Walker, M.; Wen, S.W.; Singh, S.; Amath, A.; Hodge, M.; Chen, I. Endometriosis and adverse maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsikouras, P.; Oikonomou, E.; Bothou, A.; Chaitidou, P.; Kyriakou, D.; Nikolettos, K.; Andreou, S.; Gaitatzi, F.; Nalbanti, T.; Peitsidis, P.; et al. The Impact of Endometriosis on Pregnancy. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekaru, K.; Masamoto, H.; Sugiyama, H.; Asato, K.; Heshiki, C.; Kinjyo, T.; Aoki, Y. Endometriosis and pregnancy outcome: Are pregnancies complicated by endometriosis a high-risk group? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 172, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Liu, X.; Sheng, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, S. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of pregnancy-related complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes in singleton pregnancies: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 73–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalechi, M.; Di Stefano, G.; Fornelli, G.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P. Impact of endometriosis on the ovarian follicles. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 92, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazot, M.; Daraï, E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: Clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccella, S.; Manzoni, P.; Cromi, A.; Marconi, N.; Gisone, B.; Miraglia, A.; Biasoli, S.; Zorzato, P.C.; Ferrari, S.; Lanzo, G.; et al. Pregnancy after Endometriosis: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes according to the Location of the Disease. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, S91–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Parazzini, F.; Pietropaolo, G.; Cipriani, S.; Frattaruolo, M.; Fedele, L. Pregnancy outcome in women with peritoneal, ovarian and rectovaginal endometriosis: A retrospective cohort study. BJOG 2012, 119, 1538–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V.; Peltier, M.R.; Chavez, M.R.; Kirby, R.S.; Getahun, D.; Vintzileos, A.M. Recurrence of ischemic placental disease. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bi, S.; Du, L.; Gong, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, W.; Shen, X.; Tang, J.; Ren, L.; Chai, G.; et al. Effect of previous placenta previa on outcome of next pregnancy: A 10-year retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, T.v.d.; Schoubroeck, D. van Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: State of the art. Best. Pract. research. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, M.K. Prediction and Prevention of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 234. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelabor Rupture of Membranes: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 217. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e80–e97. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [CrossRef]

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e237–e260. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Updates in Women’s Health Care Summary: Liver Disease: Reproductive Considerations. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, 236. [CrossRef]

- Gordijn, S.J.; Beune, I.M.; Thilaganathan, B.; Papageorghiou, A.; Baschat, A.A.; Baker, P.N.; Silver, R.M.; Wynia, K.; Ganzevoort, W. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: A Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauniaux, E.; Bhide, A.; Kennedy, A.; Woodward, P.; Hubinont, C.; Collins, S.; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Prenatal diagnosis and screening. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 140, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.M.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Panina-Bordignon, P.; Vercellini, P.; Candiani, M. The distinguishing cellular and molecular features of the endometriotic ovarian cyst: From pathophysiology to the potential endometrioma-mediated damage to the ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.; Hill, A.S.; Beste, M.T.; Kumar, M.P.; Chiswick, E.; Fedorcsak, P.; Isaacson, K.B.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Griffith, L.G.; Qvigstad, E. Peritoneal fluid cytokines related to endometriosis in patients evaluated for infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 1191–1199.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-M.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Song, N. Inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, TNF-α and peritoneal fluid flora were associated with infertility in patients with endometriosis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2513–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado-Torroglosa, I.; García-Velasco, J.A.; Alecsandru, D. The Impacts of Inflammatory and Autoimmune Conditions on the Endometrium and Reproductive Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.-W.; Norwitz, G.A.; Pavlicev, M.; Tilburgs, T.; Simón, C.; Norwitz, E.R. Endometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Godbole, G.; Modi, D. Decidual Control of Trophoblast Invasion. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 75, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, M.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Mehdizadehkashi, A.; Eftekhar, T.; Asemi, Z. The role of inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and apoptosis in the pathophysiology of endometriosis: Basic science and new insights based on gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 19384–19392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breintoft, K.; Pinnerup, R.; Henriksen, T.; Rytter, D.; Uldbjerg, N.; Forman, A.; Arendt, L.H. Endometriosis and Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J.; Sun, J.; Min, B.; Song, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, B.; Hwang, K.; Lee, T.; Jeon, H.; Kim, S. Endometriosis and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullo, F.; Spagnolo, E.; Saccone, G.; Acunzo, M.; Xodo, S.; Ceccaroni, M.; Berghella, V. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 667–6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgökçe, Ç.; Öçal, A.; Ermiş, I. Expression of NF-κB and VEGF in normal placenta and placenta previa patients. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ. Wroc. Med. Univ. 2022, 32, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, A.; Dagdeviren, G.; Yucel Celik, O.; Karatas Sahin, E.; Obut, M.; Cayonu Kahraman, N.; Celen, S. Systemic immune-inflammation index to predict placenta accreta spectrum and its histological subtypes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Ferrero, S.; Mangili, G.; Bergamini, A.; Inversetti, A.; Giorgione, V.; Viganò, P.; Candiani, M. A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: Diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 70–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunietz, G.; Holzman, C.; McKane, P.; Li, C.; Boulet, S.; Todem, D.; Kissin, D.; Copeland, G.E.; Bernson, D.; Sappenfield, W.; et al. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of preterm birth among primiparas. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 974–9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.; Breheny, S.; Jaques, A.M.; Halliday, J.L.; Baker, G.; Healy, D. Preterm birth, ovarian endometriomata, and assisted reproduction technologies. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpora, M.G.; Tomao, F.; Ticino, A.; Piacenti, I.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Simonetti, S.; Imperiale, L.; Sangiuliano, C.; Masciullo, L.; Manganaro, L.; et al. Endometriosis and Pregnancy: A Single Institution Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, W.; Cao, L. Miscarriage on Endometriosis and Adenomyosis in Women by Assisted Reproductive Technology or with Spontaneous Conception: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 4381346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, J.P.; Yu, O.; Schulze-Rath, R.; Grafton, J.; Hansen, K.; Reed, S.D. Incidence, prevalence, and trends in endometriosis diagnosis: A United States population-based study from 2006 to 2015. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, e1–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnancy at Age 35 Years or Older: ACOG Obstetric Care Consensus No. 11. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 348–366. [CrossRef]

- Mannini, L.; Sorbi, F.; Noci, I.; Ghizzoni, V.; Perelli, F.; Tommaso, M.D.; Mattei, A.; Fambrini, M. New adverse obstetrics outcomes associated with endometriosis: A retrospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 295, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, Y.S.; Ziauddeen, N.; Stuart, B.; Alwan, N.A.; Cheong, Y. The role of parity in the relationship between endometriosis and pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Fertil. 2023, 4, e220070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadjoo, K.; Gorgin, A.; Maleki, N.; Mohazzab, A.; Armand, M.; Hadavandkhani, A.; Sehat, Z.; Eghbal, A.F. Pregnancy-related complications in patients with endometriosis in different stages. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2024, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Control Group n = 957 (84.9%) | Ovarian Endometriosis Group n = 170 (15.1%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 27.5 ± 4.4 | 26.1 ± 4.2 | 0.053 a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 3.5 | 24.6 ± 3.5 | 0.563 a |

| Gravida | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | <0.001 b |

| Parity | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.001 b |

| Nulliparous | 629 (65.7%) | 92 (54.1%) | 0.004 c |

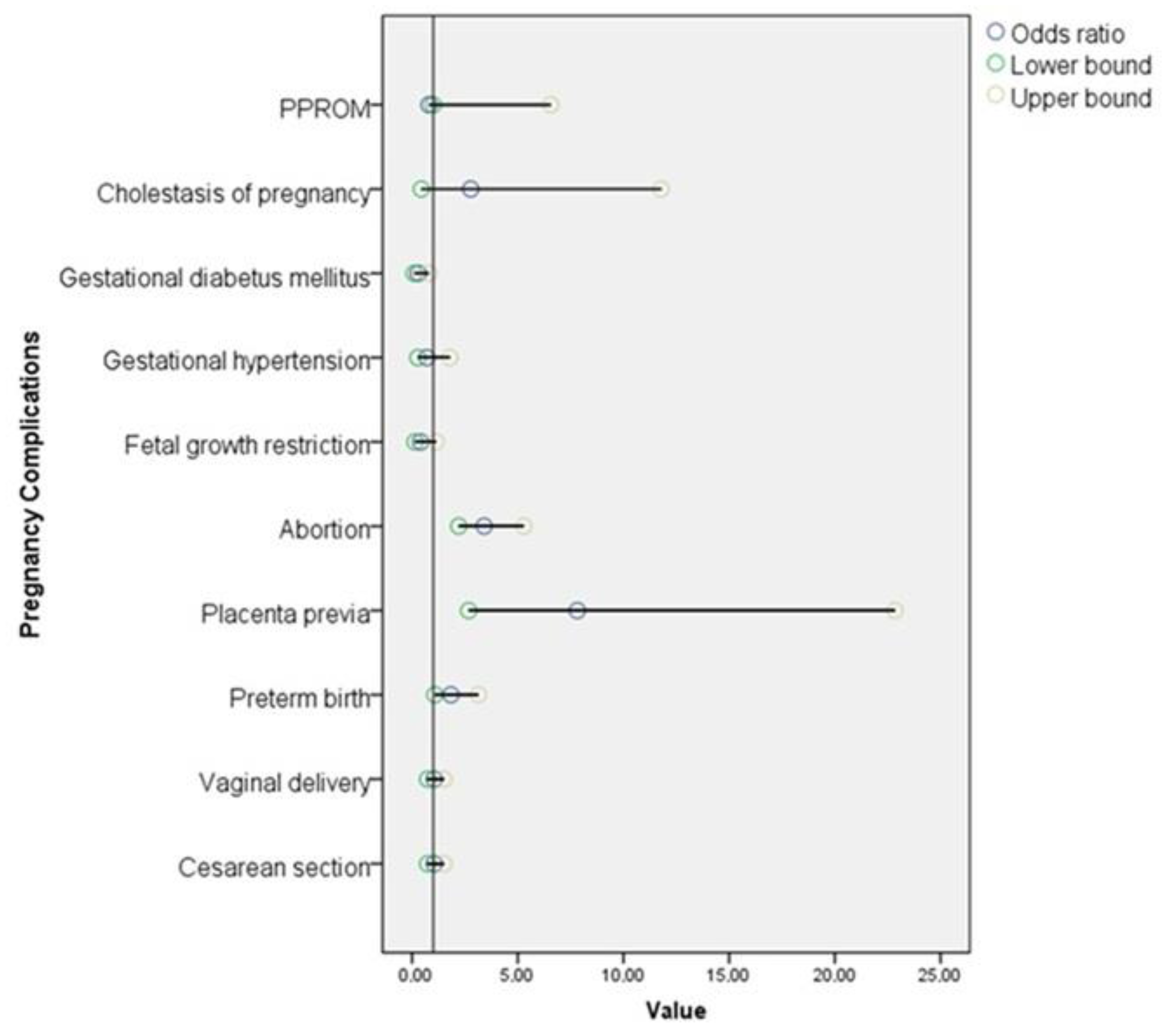

| Parameter | Control Group n = 957 (84.9%) | Ovarian Endometriosis Group n = 170 (15.1%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPROM | 7 (0.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.80 (1–6.57) | 1 a |

| Abruptio placenta | 3 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | NA | 1 a |

| Cholestasis of pregnancy | 5 (0.5%) | 2 (1.2%) | 2.27 (0.44–11.78) | 0.282 a |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 47 (4.9%) | 4 (2.4%) | 0.48 (0.16–0.87) | 0.139 a |

| Gestational hypertension | 40 (4.2%) | 5 (2.9%) | 0.70 (0.27–1.79) | 0.447 b |

| Fetal growth restriction | 54 (5.6%) | 4 (2.4%) | 0.40 (0.14–1.13) | 0.073 a |

| Abortion | 72 (7.5%) | 37 (21.8%) | 3.41 (2.21–5.29) | <0.001 b |

| Placenta previa | 6 (0.6%) | 8 (4.7%) | 7.82 (2.68–22.85) | <0.001 b |

| Preterm birth | 77 (8.8%) | 20 (15%) | 1.84 (1.08–3.13) | 0.022 b |

| Vaginal delivery | 437 (49.4%) | 64 (48.1%) | 1.05 (0.73–1.51) | 0.777 b |

| Cesarean section | 447 (50.6%) | 69 (51.9%) | 1.05 (0.73–1.51) | 0.777 b |

| Parameter | Complication Absent | Complication Present | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPROM | Diameter of cyst | 54.2 ± 24.8 | 32 | 0.375 a |

| Bilaterality | 26 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 b | |

| Abruptio placenta | Diameter of cyst | 54.07 ± 24.8 | NA | NA |

| Bilaterality | 26 (15.3%) | NA | NA | |

| Cholestasis of pregnancy | Diameter of cyst | 54.17 ± 24.9 | 45.75 ± 8.1 | 0.363 a |

| Bilaterality | 26 (15.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 b | |

| Gestational diabetus mellitus | Diameter of cyst | 54.09 ± 25.1 | 53.37 ± 13.3 | 0.923 a |

| Bilaterality | 25 (15.1%) | 1 (25%) | 0.489 b | |

| Gestational hypertension | Diameter of cyst | 54.14 ± 24.45 | 51.9 ± 40 | 0.843 a |

| Bilaterality | 24 (14.5%) | 2 (40%) | 0.168 b | |

| Fetal growth restriction | Diameter of cyst | 54.41 ± 24.95 | 40 ± 18.01 | 0.253 a |

| Bilaterality | 26 (15.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 b | |

| Miscarriage | Diameter of cyst | 54.91 ± 24.69 | 51.06 ± 25.59 | 0.407 a |

| Bilaterality | 21 (15.8%) | 5 (13.5%) | 0.734 c | |

| Placenta previa | Diameter of cyst | 54.02 ± 24.81 | 51.62 ± 27.72 | 0.776 a |

| Bilaterality | 24 (14.8%) | 2 (25%) | 0.353 b | |

| Pregnancy complications | Diameter of cyst | 52.46 ± 25.31 | 55.38 ± 24.56 | 0.447 a |

| Bilaterality | 9 (11.8%) | 17 (18.1%) | 0.261 b | |

| Preterm birth | Diameter of cyst | 54.47 ± 24.62 | 57.4 ± 25.62 | 0.628 a |

| Bilaterality | 17 (15%) | 4 (20%) | 0.522 b | |

| Cesarean section | Diameter of cyst | 52.04 ± 21.12 | 57.57 ± 27.49 | 0.198 a |

| Bilaterality | 10 (15.6%) | 11 (15.9%) | 0.960 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ozkan, H.D.; Ozkan, M.A.; Filiz, A.A.; Karakaya, M.E.; Engin-Ustun, Y. The Effect of Ovarian Endometriosis on Pregnancy Outcomes in Spontaneous Pregnancies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103468

Ozkan HD, Ozkan MA, Filiz AA, Karakaya ME, Engin-Ustun Y. The Effect of Ovarian Endometriosis on Pregnancy Outcomes in Spontaneous Pregnancies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103468

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzkan, Halis Dogukan, Merve Ayas Ozkan, Ahmet Arif Filiz, Muhammed Enes Karakaya, and Yaprak Engin-Ustun. 2025. "The Effect of Ovarian Endometriosis on Pregnancy Outcomes in Spontaneous Pregnancies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103468

APA StyleOzkan, H. D., Ozkan, M. A., Filiz, A. A., Karakaya, M. E., & Engin-Ustun, Y. (2025). The Effect of Ovarian Endometriosis on Pregnancy Outcomes in Spontaneous Pregnancies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103468