Outcomes of Different Regimens of Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

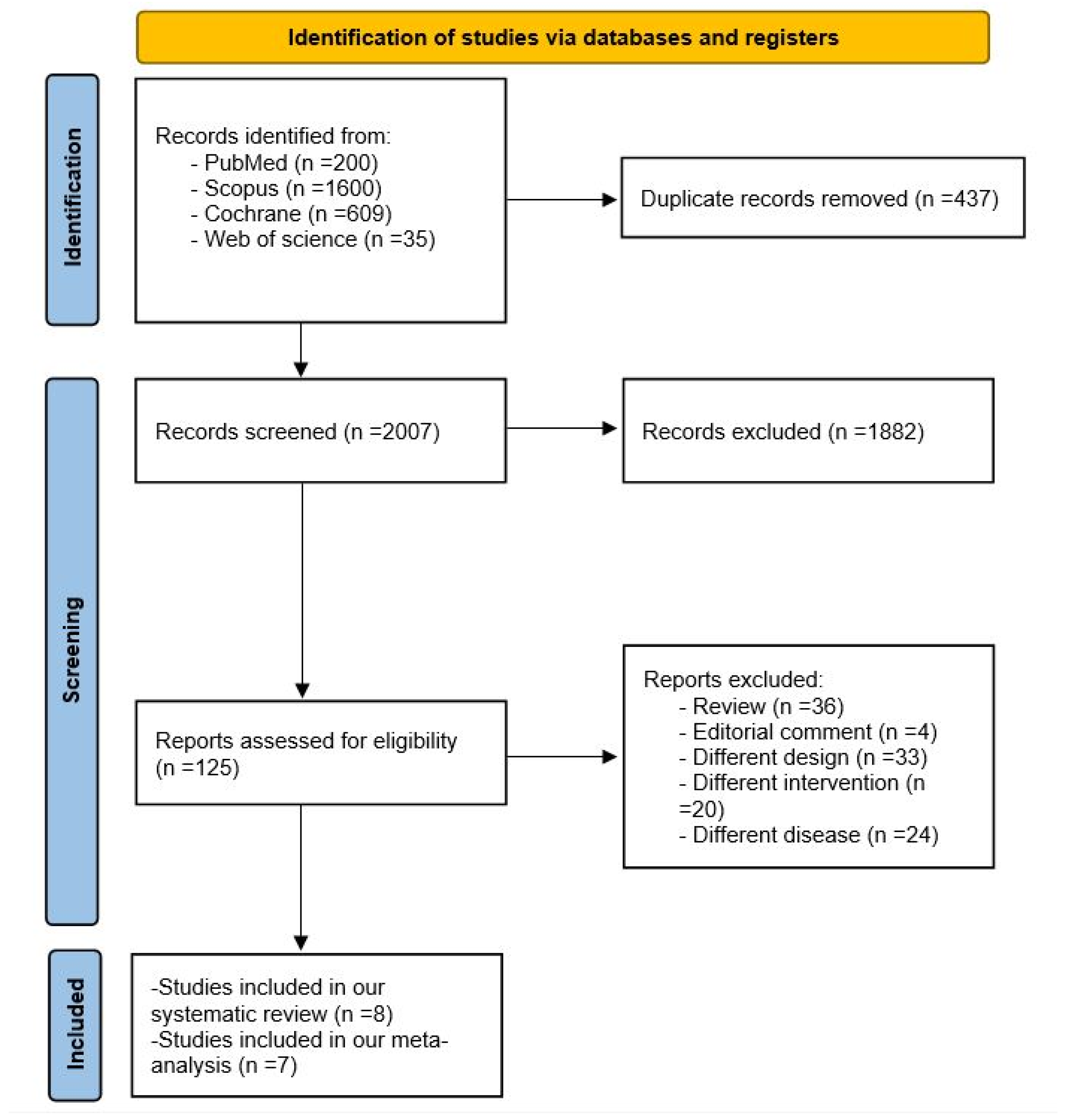

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Outcomes and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics and Narrative Synthesis

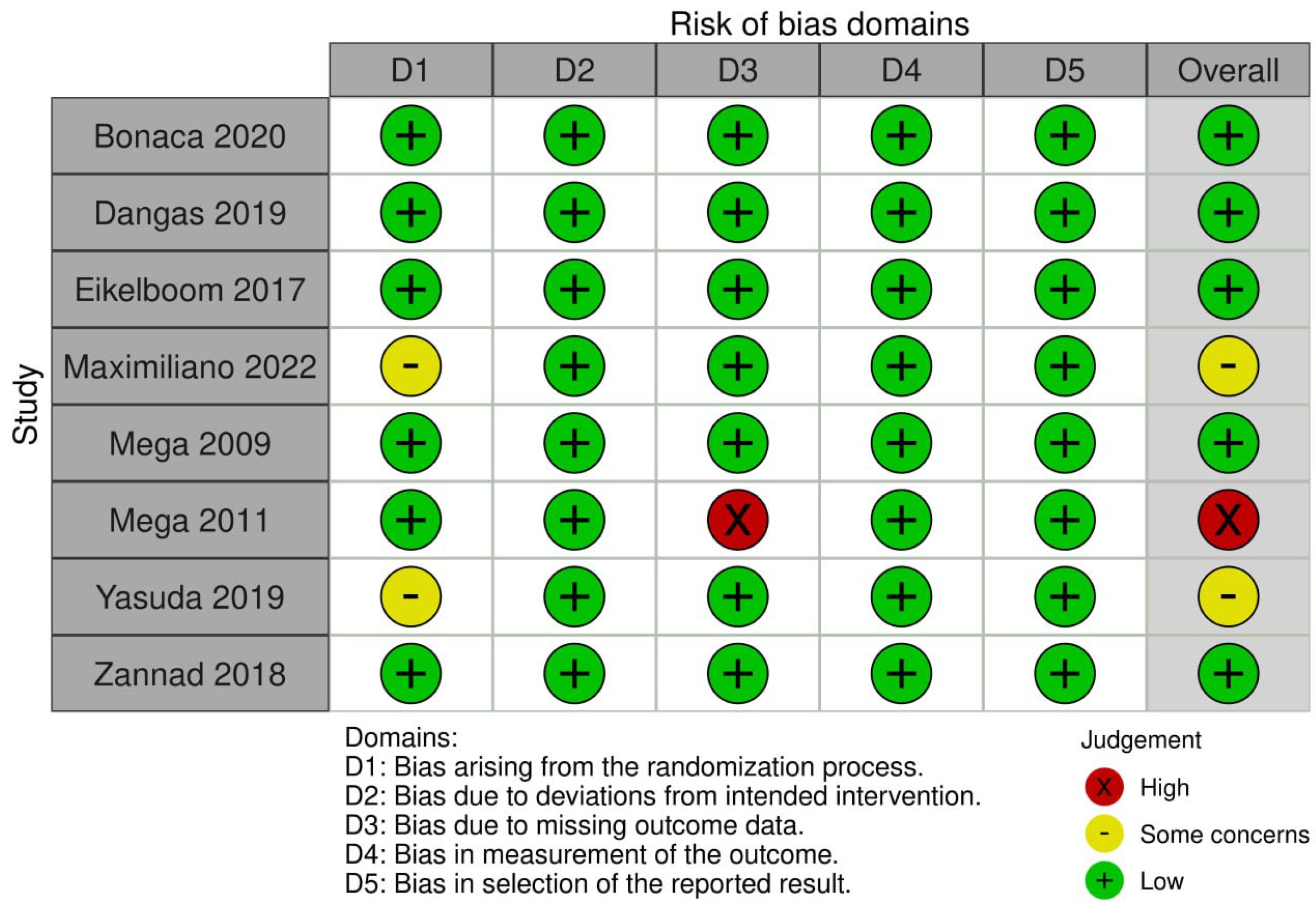

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Meta-Analysis

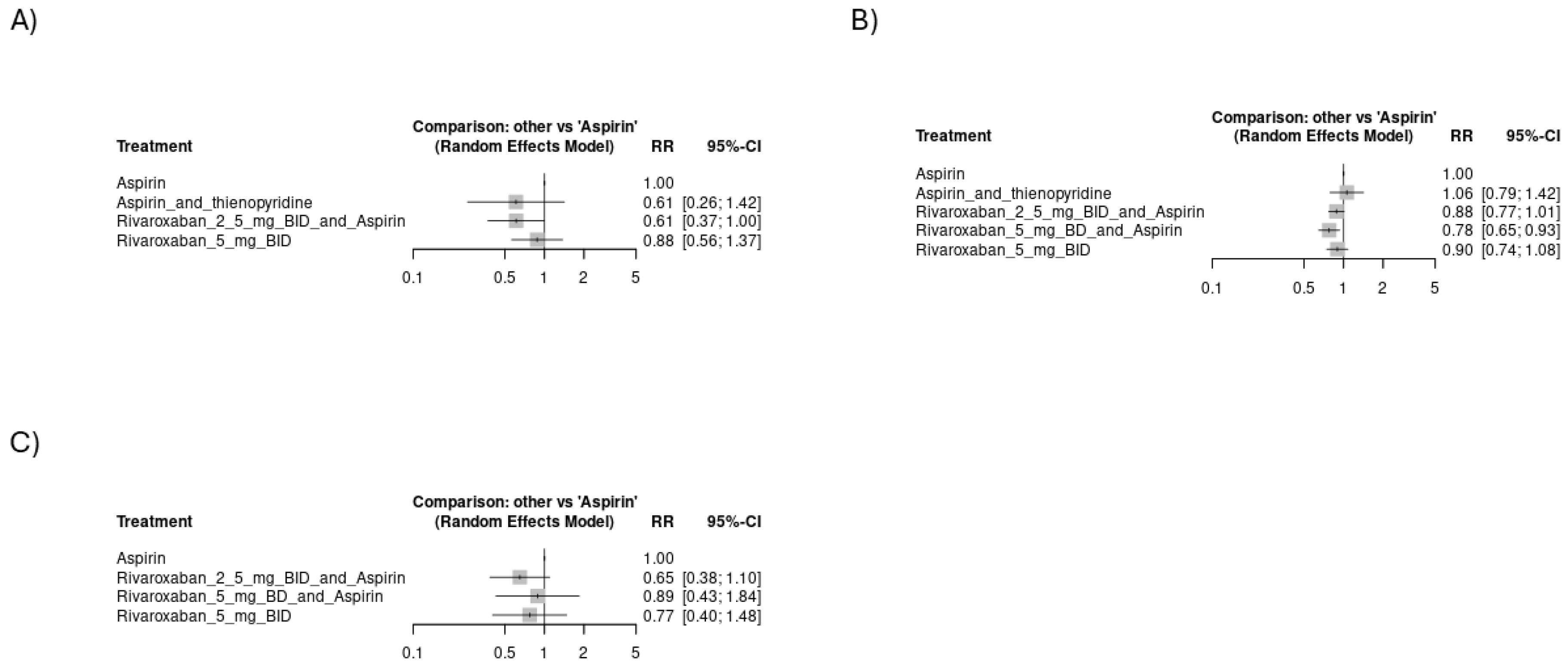

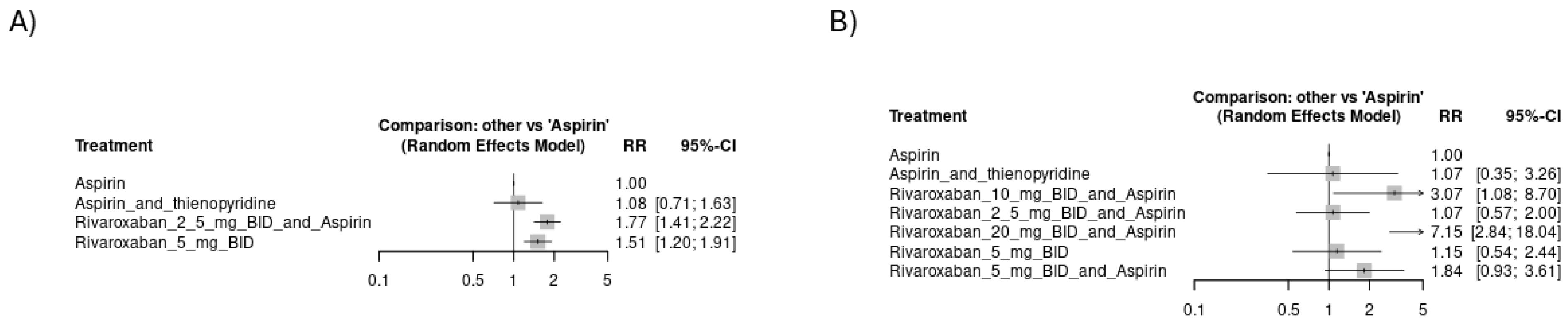

3.4.1. Risk of Thromboembolic Events

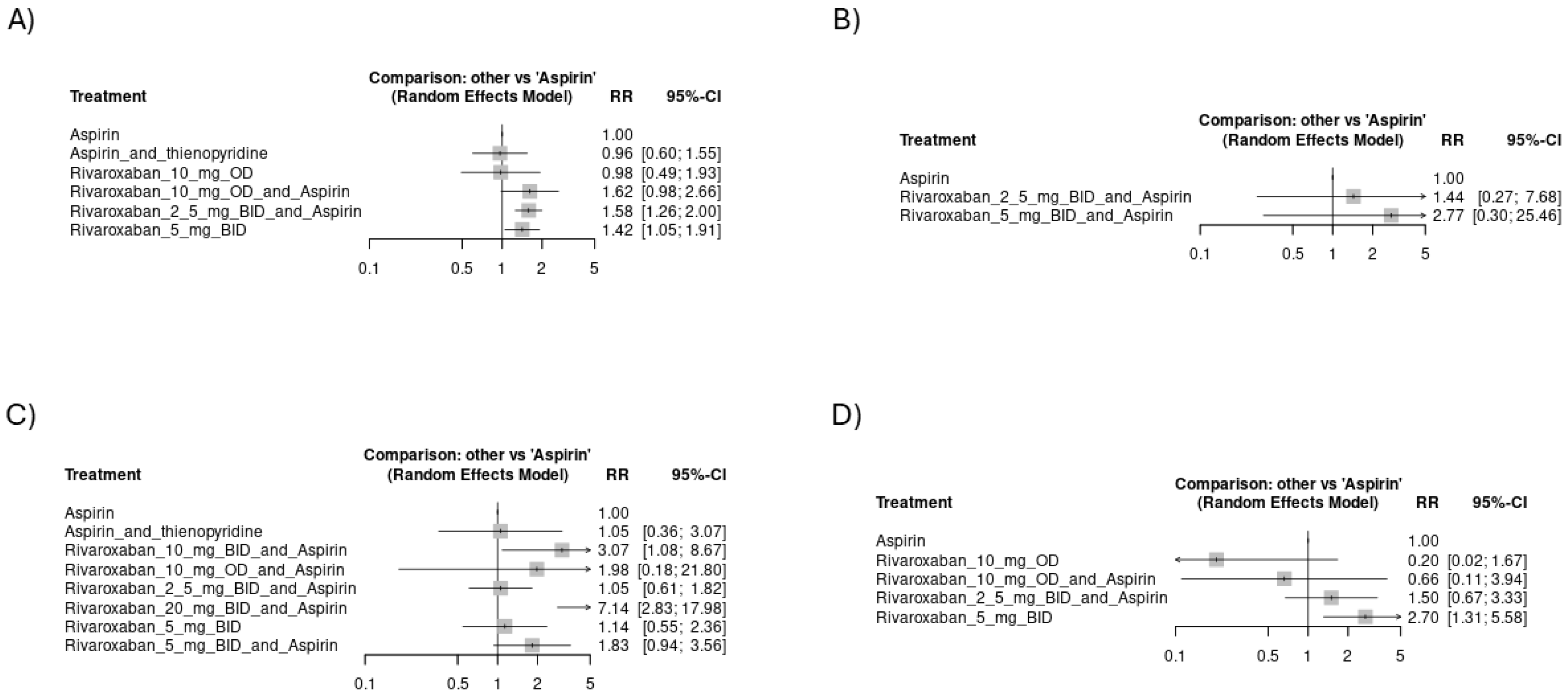

3.4.2. Risk of Hemorrhagic Events

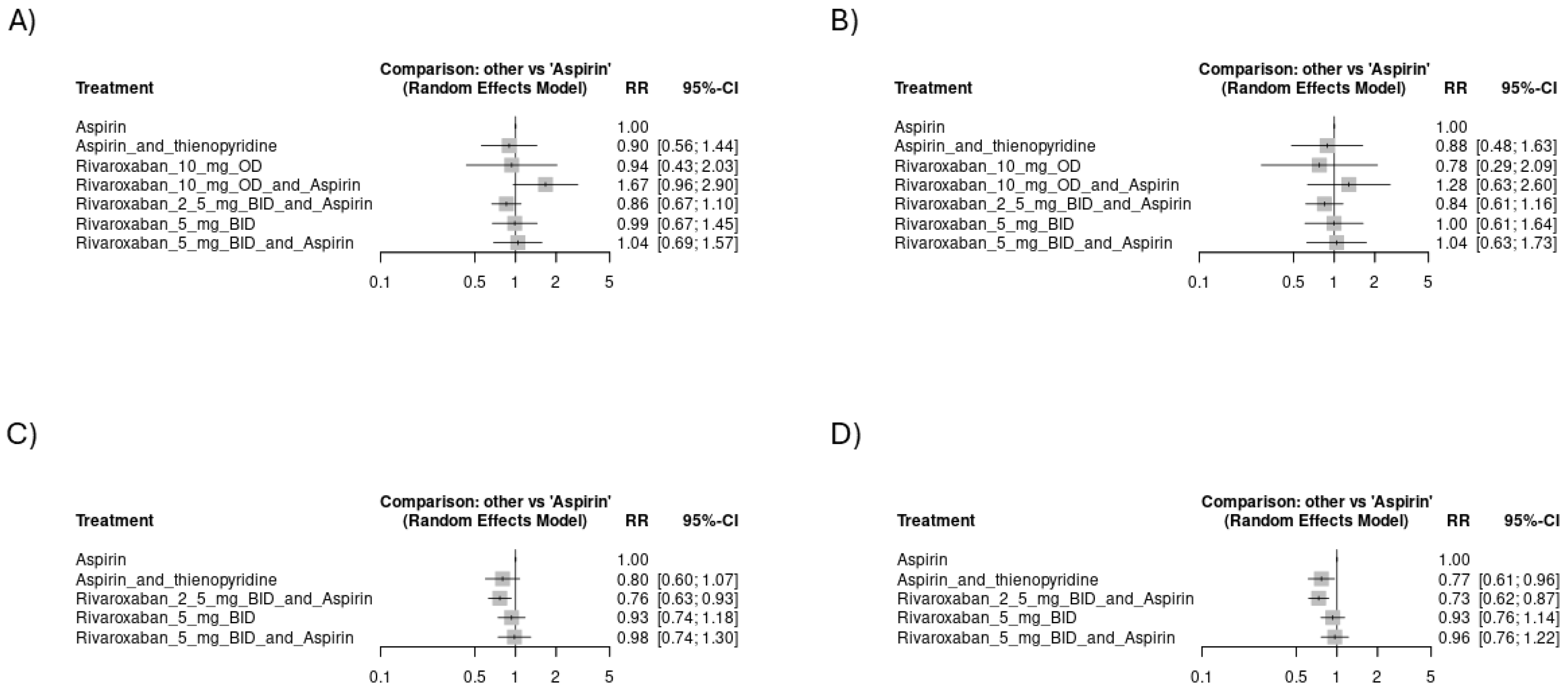

3.4.3. Mortality Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flora, G.D.; Nayak, M.K. A Brief Review of Cardiovascular Diseases, Associated Risk Factors and Current Treatment Regimes. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 4063–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, G.; Goldhaber, S.Z. Venous Thromboembolism and Atherothrombosis An Integrated Approach. Circulation 2010, 121, 2146–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jame, S.; Barnes, G. Stroke and thromboembolism prevention in atrial fibrillation. Heart 2020, 106, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 149. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Gornik, H.L.; Aronow, H.D.; Goodney, P.P.; Arya, S.; Brewster, L.P.; Byrd, L.; Chandra, V.; Drachman, D.E.; Eaves, J.M.; Ehrman, J.K.; et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251 (accessed on 3 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Guedeney, P.; Mehran, R.; Collet, J.P.; Claessen, B.E.; Ten Berg, J.; Dangas, G.D. Antithrombotic Therapy After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Collins, R.; Emberson, J.; Godwin, J.; Peto, R.; Buring, J.; Hennekens, C.; Kearney, P.; Meade, T.; et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: Collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009, 373, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlen, M.; Abdelnoor, M.; Smith, P.; Erikssen, J.; Arnesen, H. Warfarin, Aspirin, or Both after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Emmady, P.D. Rivaroxaban. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557502/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Yuan, J. Efficacy and safety of adding rivaroxaban to the anti-platelet regimen in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, J.; Braunwald, E.; Mohanavelu, S.; Burton, P.; Poulter, R.; Misselwitz, F.; Hricak, V.; Barnathan, E.S.; Bordes, P.; Witkowski, A.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46): A randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, J.L.; Braunwald, E.; Wiviott, S.D.; Bassand, J.P.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bode, C.; Burton, P.; Cohen, M.; Cook-Bruns, N.; Fox, K.A.; et al. Rivaroxaban in Patients with a Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikelboom, J.W.; Connolly, S.J.; Bosch, J.; Dagenais, G.R.; Hart, R.G.; Shestakovska, O.; Diaz, R.; Alings, M.; Lonn, E.M.; Anand, S.S.; et al. Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannad, F.; Anker, S.D.; Byra, W.M.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Fu, M.; Gheorghiade, M.; Lam, C.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Neaton, J.D.; Nessel, C.C.; et al. Rivaroxaban in Patients with Heart Failure, Sinus Rhythm, and Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangas, G.D.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Wöhrle, J.; Søndergaard, L.; Gilard, M.; Möllmann, H.; Makkar, R.R.; Herrmann, H.C.; Giustino, G.; Baldus, S.; et al. A Controlled Trial of Rivaroxaban after Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoB 2: A Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials|Cochrane Bias [Internet]. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Owen, R.K.; Bradbury, N.; Xin, Y.; Cooper, N.; Sutton, A. MetaInsight: An interactive web-based tool for analyzing, interrogating, and visualizing network meta-analyses using R-shiny and netmeta. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S.; Kaikita, K.; Akao, M.; Ako, J.; Matoba, T.; Nakamura, M.; Miyauchi, K.; Hagiwara, N.; Kimura, K.; Hirayama, A.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation with Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaca, M.P.; Bauersachs, R.M.; Anand, S.S.; Debus, E.S.; Nehler, M.R.; Patel, M.R.; Fanelli, F.; Capell, W.H.; Diao, L.; Jaeger, N.; et al. Rivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease after Revascularization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximiliano, C.L.; Jaime, G.C.; Erika, M.H. Rivaroxaban plus aspirin versus acenocoumarol to manage recurrent venous thromboembolic events despite systemic anticoagulation with rivaroxaban. Thromb. Res. 2023, 222, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Shen, C. Efficacy and safety of aspirin combined with warfarin after acute coronary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Herz 2017, 42, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Said, S.; Kaier, K.; Sumaya, W.; Alsaid, D.; Duerschmied, D.; Storey, R.F.; Gibson, C.M.; Westermann, D.; Alabed, S. Non-vitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) after acute myocardial infarction: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 1, CD014678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gomes, T.; Wells, P.S.; Pequeno, P.; Johnson, A.; Sholzberg, M. Evaluation of definitions for oral anticoagulant-associated major bleeding: A population-based cohort study. Thromb. Res. 2022, 213, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, T. The clinical outcomes of different doses of rivaroxaban in patients with isolated distal deep vein thrombosis. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2024, 12, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Liao, Q.Q.; Zhu, K.W.; Yao, Y.; Cui, X.J.; Chen, P.; Bi, Y.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Different Doses of Rivaroxaban and Risk Factors for Bleeding in Elderly Patients with Venous Thromboembolism: A Real-World, Multicenter, Observational, Cohort Study. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. A real-world study of different doses of rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Medicine 2024, 103, e38053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID | Study Time and Sites | Protocol Number | Total Number of Patients | Disease Details | Rivaroxaban Arm Details | Control Arm Details | Additional Therapy Details | Follow up Duration (months) | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonaca et al. (2020) [20] | 2015–2018 34 countries | NCT02504216 | 6564 | Type of disease: moderate to severe symptomatic lower extremity atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease. Participant requirements: they should have undergone successful peripheral revascularization distal to the external iliac artery for symptomatic PAD (peripheral artery disease) within 10 days prior to randomization. | Twice daily oral Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg and aspirin 100 mg daily | Placebo plus aspirin | Clopidogrel may be administered for up to 6 months following revascularization at the discretion of the investigator. | 28 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of acute limb ischemia, major amputation due to vascular issues, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes. The main focus on safety was the occurrence of major bleeding, as defined by the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) classification. |

| Dangas et al. (2020) [15] | 2015–2018 16 countries | NCT02556203 | 1644 | Type of disease: transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for the treatment of aortic valve stenosis. Patient requirements: the patient should have undergone a successful TAVR, which is defined as the proper placement of an approved bioprosthetic aortic valve into the correct anatomical location, with the valve functioning as intended and without any complications during the procedure. | Once daily oral 10 mg rivaroxaban and aspirin (75–100 mg). | Oral 75–100 mg of aspirin and 75 mg of clopidogrel daily. | NR | 3 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of death from any cause or thromboembolic events, such as stroke, heart attack, symptomatic valve thrombosis, systemic embolism (not involving the central nervous system), deep-vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism. The main focus on safety was a combination of life-threatening, disabling, or major bleeding. |

| Eikelboom et al. (2017) [13] | 2013–2016 33 countries | NCT01776424 | 27395 | Type of disease: coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD). CAD: one of the following: - myocardial infarction within the past 20 years - multi-vessel coronary artery disease - history of stable or unstable angina - previous multi-vessel percutaneous coronary intervention - previous multi-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery. PAD: one of the following: - previous aorto-femoral bypass surgery, limb bypass surgery, or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty revascularization of the iliac, or infra-inguinal arteries - previous limb or foot amputation for arterial vascular disease - history of intermittent claudication and one or more of the following: (1) ankle/arm blood pressure (BP) ratio < 0.90 (2) significant peripheral artery stenosis (≥50%) documented by angiography or duplex ultrasound - previous carotid revascularization or asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis ≥50% as diagnosed by duplex ultrasound or angiography | Twice daily oral Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg and aspirin 100 mg daily. | Group 1 rivaroxaban alone (5 mg orally twice a day). Group 2 aspirin alone (100 mg orally once a day). | NR | 23 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of the first instance of stroke, heart attack, or cardiovascular death. The main focus on safety was significant bleeding, which was defined as fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding into a critical organ or area, bleeding at the site of surgery requiring further operation, or bleeding requiring a visit or admission to the hospital. |

| Maximiliano et al. (2023) [21] | 2021–2022 Mexico | NCT05515120 | 62 | Type of disease: venous thromboembolism. Participant requirements: individuals should meet the following criteria: (I) have experienced a confirmed initial episode of venous thromboembolism, such as upper extremity deep vein thrombosis, proximal lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism; (II) have documented recurrent venous thromboembolism, including new or extended upper extremity deep vein thrombosis, proximal lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism, while receiving systemic anticoagulation treatment (specifically rivaroxaban 20 mg once a day). | Once daily 20 mg of oral rivaroxaban and 300 mg of aspirin | Acenocoumarol oral tablet. | NR | 3 | The primary measure of effectiveness was the presence of thromboembolic events (recurrent ipsilateral DVT, recurrent contralateral DVT, PE, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction). The main focus on safety was minor bleeding according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) scale. |

| Mega et al. (2009) [11] | 2006–2008 27 countries | NCT00402597 | 3491 | Type of disease: acute coronary syndrome. Patient requirements: patients should have experienced symptoms suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome lasting at least 10 min at rest. This includes a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or a diagnosis of non-STEMI or unstable angina with specific indicators, such as raised cardiac enzyme markers, 1 mm or more ST-segment deviation, or a TIMI risk score of 3 or more | Rivaroxaban 5 mg orally plus aspirin (75–100) mg. Rivaroxaban 10 mg orally plus aspirin (75–100) mg. Rivaroxaban 20 mg orally plus aspirin (75–100) mg. Group 1: once daily. Group 2: twice daily (the same total daily dose). | Group 1: oral aspirin (75–100) mg. Group 2: oral rivaroxaban (5, 10, 15, 20) mg, aspirin (75–100) mg, and thienopyridine. Group 3: oral aspirin (75–100) mg and thienopyridine | According to the use of thienopyridine, the group was divided into two strata (stratum one received aspirin only, while stratum two received aspirin plus a thienopyridine). | 6 | The primary measure of effectiveness was the time to the first occurrence of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or severe recurrent ischemia requiring revascularization within 6 months from enrollment. The main focus on safety was clinically significant bleeding, defined as TIMI major, TIMI minor, or requiring medical attention. Bleeding requiring medical attention was further defined as a bleeding event that necessitated medical treatment, surgical treatment, or laboratory assessment, and did not meet criteria for TIMI major or minor bleeding. |

| Mega et al. (2012) [12] | 2008–2011 44 countries | NCT00809965 | 15526 | Type of Disease: acute coronary syndrome. Participant requirements: - must have experienced either ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or unstable angina - patients under 55 years of age who have either diabetes mellitus or a prior myocardial infarction along with the index event. | Group 1: twice daily of oral rivaroxaban 2.5 mg and low dose aspirin. Group 2: twice daily of oral rivaroxaban 5 and low dose aspirin. | Placebo plus low dose aspirin. | Patients were to receive thienopyridine (either clopidogrel or ticlopidine) according to the national or local guidelines. | 31 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of death from cardiovascular causes, heart attack, or stroke (either caused by blockage of blood vessels or bleeding in the brain). The main focus on safety was major bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). |

| Yasuda et al. (2019) [19] | 2015–2017 Japan | NCT02642419 | 2240 | Type of disease: atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease. Participant requirements: they should have a score of at least 1 on the CHADS2 scale. Additionally, patients should meet at least one of the following criteria: - a history of PCI, including angioplasty with or without stenting, at least 1 year before enrollment - a history of angiographically confirmed coronary artery disease (with stenosis of ≥50%) not requiring revascularization - a history of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) at least 1 year before enrollment. | Once daily oral 10 mg rivaroxaban if creatinine clearance (15–49) per minute plus aspirin, or 15 mg if creatinine clearance of ≥50 mL per minute | Once daily oral 10 mg rivaroxaban if creatinine clearance (15–49) per minute, or 15 mg if creatinine clearance of ≥50 mL per minute. | Patients in the combination group may take either aspirin or a P2Y12 inhibitor, according to the discretion of the treating physician. | 24.1 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, or death from any cause. The main focus on safety was the occurrence of major bleeding, as per the criteria established by the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. |

| Zannad et al. (2018) [14] | 2013–2017 32 countries | NCT01877915 | 5022 | Type of disease: heart failure. Participant requirements: participants should have a history of chronic heart failure lasting at least 3 months, a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, and coronary artery disease, and those have been treated for an episode of worsening heart failure within the past 21 days. Additionally, their plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) should be at least 200 pg. per milliliter, or their N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) should be at least 800 pg. per milliliter | Twice daily oral rivaroxaban 2.5 mg and aspirin. | Placebo plus (aspirin or dual antiplatelet). | Single or dual antiplatelet therapy was allowed. | 21.1 | The primary measure of effectiveness was a combination of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, or stroke. Additional measures of effectiveness included death from cardiovascular causes, rehospitalization for worsening heart failure, and the combination of death from any cause or rehospitalization for worsening heart failure. The main focus on safety was a combination of fatal bleeding or bleeding into a critical space with the potential for causing permanent disability. |

| Study ID | Study Groups (n) | Age, Mean (SD) | Sex (Male), No. (%) | BMI, Mean (SD) | E-GFR, Mean (SD) | Hypertension, No. (%) | Current Smoking, No. (%) | Diabetes, No. (%) | Prior MI, No. (%) | Stroke, No. (%) | Dyslipidemia, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonaca et al. (2020) [20] | Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg group (3286) | 67 (8.8) | 2439 (74.2%) | 26.1 (4.3) | NR | 2684 (81.7%) | 1147 (39.3%) | 1313 (40%) | 365 (11.1%) | NR | 1971 (60%) |

| Aspirin group (3278) | 67 (8.8) | 2421 (73.8%) | 26.1 (4.3) | NR | 2658 (81.1%) | 1132 (34.5%) | 1316 (40.1%) | 349 (10.6%) | NR | 1968 (60%) | |

| Dangas et al. (2020) [15] | Rivaroxaban 10 mg group (826) | 80.4 (7.1) | 426 (51.6%) | 28.1 (5.5) | 73.4 (23.8) | 720 (82.2%) | NR | 236 (28.6%) | NR | 51 (6.20%) | NR |

| Aspirin group (818) | 80.8 (6) | 405 (49.5%) | 28.2 (5.7) | 73.2 (23.3) | 697 (85.2%) | NR | 235 (28.7%) | NR | 35 (4.3%) | NR | |

| Eikelboom et al. (2017) [13] | Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg group (9152) | 68.3 (7.9) | 7093 (77.5%) | 28.3 (4.8) | NR | 6907 (75.5%) | 1944 (21.2%) | 3448 (37.7%) | 5654 (61.8%) | 351 (3.8%) | NR |

| Rivaroxaban 5 mg only group (9117) | 68.2 (7.9) | 7145 (88.4%) | 28.3 (4.6) | NR | 6848 (75.1%) | 1451 (21.4%) | 3419 (37.5%) | 5653 (62%) | 346 (3.8%) | NR | |

| Aspirin group (9126) | 68.2 (8) | 7137 (88.2%) | 28.4 (4.7) | NR | 6677 (75.4%) | 1972 (21.6%) | 3474 (38.1%) | 5721 (62.2%) | 335 (3.7%) | NR | |

| Maximiliano et al. (2023) [21] | Rivaroxaban 20 mg group (28) | 42.89 (15.33) | 11 (39.29%) | 26.2 | 97.5 (3.2) | 8 (28.57%) | 2 (7.14%) | 8 (28.57%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Acenocoumarol group (30) | 42.76 (15.58) | 10 (33.3%) | 25.8 | 92.9 (14.3) | 5 (16.66%) | 4 (13.3%) | 9 (30%) | NR | NR | NR | |

| Mega et al. (2009) [11] | Rivaroxaban (5, 10, 20 mg) groups (508) | 59.8 (9.2) | 340 (66.9%) | 28.5 (4.8) | 70.1 (31.1) | 387 (76.2%) | 243 (47.8%) | 102 (20.1%) | 141 (27.8%) | NR | 241 (47.4%) |

| Aspirin group (253) | 60.3 (9.3) | 182 (68%) | 28.1 (4.7) | 79.3 (27.7) | 188 (74.3%) | 129 (51%) | 55 (21.7%) | 70 (27.7%) | NR | 121 (44.3%) | |

| Rivaroxaban, aspirin and thienopyridine group (1823) | 56.5 (9.5) | 1470 (80.6%) | 28.8 (5.9) | 102.4 (31.5) | 951 (52.2%) | 1199 (65.8%) | 350 (19.2%) | 345 (18.9%) | NR | 795 (43.6%) | |

| Aspirin and thienopyridine group (907) | 57.1 (9.5) | 713 (78.6%) | 28.4 (4.7) | 99.9 (31.7) | 471 (52%) | 596 (65.8%) | 166 (18.3%) | 180 (19.9%) | NR | 393 (43.4%) | |

| Mega et al. (2012) [12] | Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg group (5174) | 61.8 (9.2) | 3875 (74.9%) | NR | 86.13 (27.7) | 3470 (67.1%) | NR | 1669 (31.31%) | 1363 (26.3%) | NR | 2448 (48.3%) |

| Rivaroxaban 5 mg group (5176) | 61.9 (9) | 3843 (43.2%) | NR | 86 (26.8) | 3499 (67.6%) | NR | 1648 (31.8%) | 1403 (27.1%) | NR | 2544 (49.1%) | |

| Aspirin group (5176) | 61.5 (9.4) | 3882 (85%) | NR | 86.4 (27.1) | 3494 (67.5%) | NR | 1647 (31.8%) | 1415 (27.3%) | NR | 2496 (48.7%) | |

| Yasuda et al. (2019) [19] | Rivaroxaban 10 mg group (1107) | 74.4 (8.2) | 876 (79.1%) | 24.5 (3.7) | 61.7 (24) | NR | 146 (13.2%) | 466 (42.1%) | 393 (35.5%) | 175 (15.8%) | NR |

| Aspirin group (1108) | 74.3 (8.3) | 875 (79%) | 24.5 (3.7) | 62.8 (25.8) | NR | 146 (13.7%) | 461 (41.6%) | 384 (34.7%) | 148 (13.4%) | NR | |

| Zannad et al. (2018) [14] | Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg group (2507) | 66.5 (10.1) | 1956 (78%) | 27.6 (5.1) | NR | 1897 (25.7%) | NR | 1024 (40.8%) | 1911 (76.2%) | 208 (8.3%) | NR |

| Aspirin group (2515) | 66.3 (10.3) | 1916 (76.2%) | 27.8 (5.3) | NR | 1886 (75%) | NR | 1028 (40.9%) | 1892 (75.2%) | 245 (9.7%) | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Salihi, M.M.; Qureshi, A.I. Outcomes of Different Regimens of Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103437

Al-Salihi MM, Qureshi AI. Outcomes of Different Regimens of Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103437

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Salihi, Mohammed Maan, and Adnan I. Qureshi. 2025. "Outcomes of Different Regimens of Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103437

APA StyleAl-Salihi, M. M., & Qureshi, A. I. (2025). Outcomes of Different Regimens of Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103437