Longitudinal Influences on Maternal–Infant Bonding at 18 Months Postpartum: The Predictive Role of Perinatal and Postpartum Depression and Childbirth Trauma

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Postpartum Psychopathology and Bonding Difficulties: Childbirth-Related Posttraumatic Symptoms and Postpartum Depression Symptoms

1.2. Perinatal Depression as an Early Risk Factor for the Development of Bonding Difficulties

2. Material and Methods

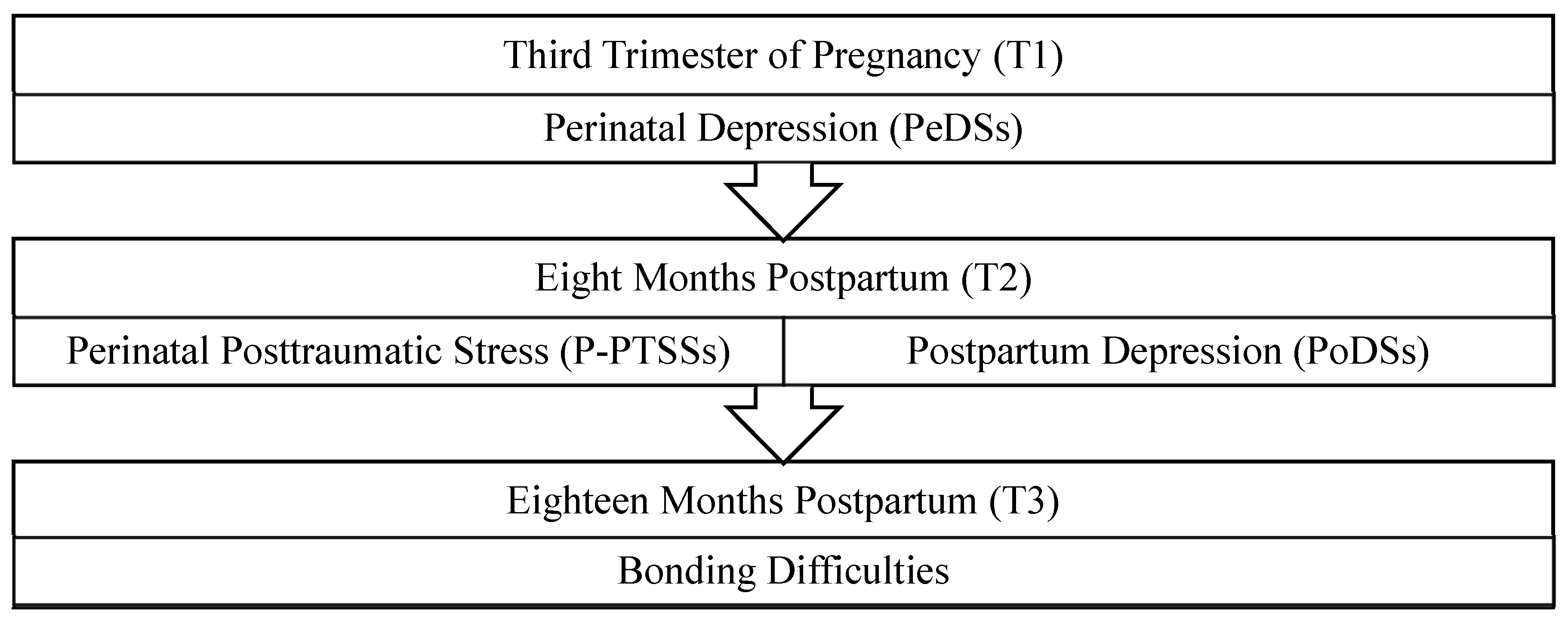

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

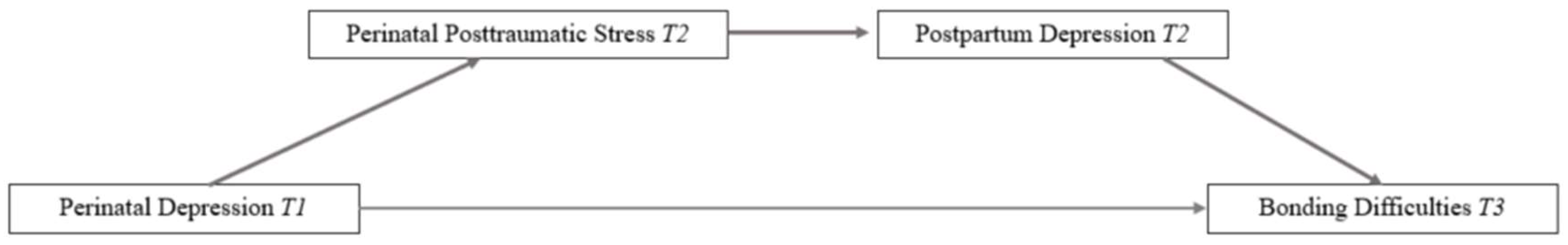

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences Between Completers and Non-Completers of Follow-Up Assessments

3.2. Bivariate Correlations Among Variables

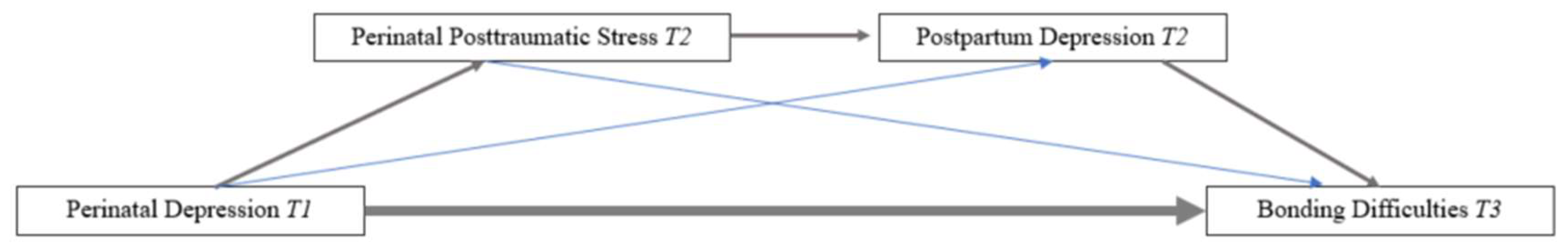

3.3. Mediational Model

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raphael-Leff, J. Women in the history of psychoanalysis: Issues of gender, generation, and the genesis of the Committee on Women and Psychoanalysis (COWAP). Psychoanal. Psychother. 2001, 18, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nakić Radoš, S.; Hairston, I.; Handelzalts, J.E. The concept analysis of parent-infant bonding during pregnancy and infancy: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 42, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Atkins, R.; Kumar, R.; Adams, D.; Glover, V. A new Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: Links with early maternal mood. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2005, 8, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios-Hernández, B. Mother-infant bonding disorders: Prevalence, risk factors, diagnostic criteria and assessment strategies. Revista de la Universidad Industrial de Santander. Salud 2016, 48, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, G.A.; Youssef, G.J.; Hagg, L.J.; Francis, L.M.; Spry, E.A.; Rossen, L.; Smith, I.; Teague, S.J.; Mansour, K.; Booth, A.; et al. Associations between maternal psychological distress and mother-infant bonding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2023, 26, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant. Ment. Health J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2001, 22, 201–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxler, E.; Thelen, K.; Muzik, M. Maternal perinatal depression-impact on infant and child development. Eur. Psychiatr. Rev. 2011, 4, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, Y.; Pike, A.; Ayers, S. Infant developmental outcomes: A family systems perspective. Infant Child. Dev. 2014, 23, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, I. Maternal rejection of the young child: Present status of the clinical syndrome. Psychopathology 2011, 44, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bas, G.A.; Youssef, G.J.; Macdonald, J.A.; Rossen, L.; Teague, S.J.; Kothe, E.J.; McIntosh, J.E.; Olsson, C.A.; Hutchinson, D.M. The role of antenatal and postnatal maternal bonding in infant development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, A.M.; Olsen, E.M.; Christiansen, E.; Houmann, T.; Landorph, S.L.; Jørgensen, T.; CCC 2000* Study Group. Predictors (0–10 months) of psychopathology at age 1½ years–a general population study in The Copenhagen Child Cohort CCC 2000. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekel, S.; Ein-Dor, T.; Berman, Z.; Barsoumian, I.S.; Agarwal, S.; Pitman, R.K. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devita, S.; Bozicevic, L.; Deforges, C.; Ciavarella, L.; Tolsa, J.F.; Sandoz, V.; Horsch, A. Early mother-infant interactions within the context of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 365, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S. Birth trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder: The importance of risk and resilience. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2017, 35, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuijfzand, S.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Horsch, A. Parental birth-related PTSD symptoms and bonding in the early postpartum period: A prospective populationbased cohort study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 570727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Sanz, M.; Berastegui, A.; Sanchez-Lopez, A. Perinatal posttraumatic stress disorder as a predictor of mother-child bonding quality 8 months after childbirth: A longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionio, C.; Di Blasio, P. Post-traumatic stress symptoms after childbirth and early mother–child interactions: An exploratory study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2014, 32, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, K.; Ayers, S. Childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder in couples: A qualitative study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S. Thoughts and emotions during traumatic birth: A qualitative study. Birth 2007, 34, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S.; Bond, R.; Bertullies, S.; Wijma, K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, Z.; Irajpour, A.; Arbabi, M. Mothers’ response to psychological birth trauma: A qualitative study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2013, 15, e10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.; Cox, J.L. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1990, 8, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, J. Risk factors for the development of postpartum depression in individuals who screened positive for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mughal, M.K.; Giallo, R.; Arshad, M.; Arnold, P.D.; Bright, K.; Charrois, E.M.; Rai, B.; Wajid, A.; Kingston, D. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 11 years postpartum: Findings from Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 328, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.M.; Youssef, G.J.; Teague, S.; Sunderland, M.; Le Bas, G.; Macdonald, J.A.; Mattick, R.P.; Allsop, S.; Elliott, E.J.; Olsson, C.A.; et al. Association of maternal and paternal perinatal depression and anxiety with infant development: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 338, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Hirvi, P.; Maria, A.; Kotilahti, K.; Tuulari, J.J.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Nissilä, I. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and child brain responses to affective touch at two years of age. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 356, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, B.F.; Kearney, J. Risk factors for postpartum de-pression: An umbrella review. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2020, 65, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Swain, A.M. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1996, 8, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Bertazzi Levy, R.; Kontos, A.; Tabb, K.; Matijasevich, A. Postpartum bonding at the beginning of the second year of child’s life: The role of postpartum depression and early bonding impairment. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 41, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Tabb, K.M.; Ziebold, C.; Matijasevich, A. The impact of postpartum depression and bonding impairment on child development at 12 to 15 months after delivery. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Arteche, A.; Fearon, P.; Halligan, S.; Goodyer, I.; Cooper, P. Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of age. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.; Litz, B.; Herman, D.; Huska, J.; Keane, T. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, USA, October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brockington, I.F.; Oates, J.; George, S.; Turner, D.; Vostanis, P.; Sullivan, M.; Loh, C.; Murdoch, C. A screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2001, 3, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Joas, J.; Möhler, E. Maternal bonding in early infancy predicts childrens’ social competences in preschool age. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 687535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, Y.; Ayers, S. Postnatal mental health and parenting: The importance of parental anger. Infant Ment. Health J. 2012, 33, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitenmüller, P.; Köhler, S.; Hirsch, O.; Christiansen, H. The impact of prepartum depression and birth experience on postpartum mother-infant bonding: A longitudinal path analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 815822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingol, F.B.; Bal, M.D. The risk factors for postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajdy, A.; Sys, D.; Pokropek, A.; Shaw, S.W.; Chang, T.Y.; Calda, P.; Acharya, G.; Ben-Zion, M.; Biron-Shental, T.; Borowski, D.; et al. Risk factors for anxiety and depression among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a web-based multinational cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 160, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, J.; Campbell, L.; Tabana, H.; Wouters, E. The pandemic of online research in times of COVID-19. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample (N = 51) | |

|---|---|

| Variable | % |

| Medical complications during pregnancy (T1) | |

| Yes | 21.6 |

| Type of delivery (T2) | |

| Natural | 74.2 |

| Cesarean section | 0.3 |

| Cesarean section with previous labor | 16.9 |

| Scheduled cesarean section | 8.0 |

| Home birth | 0.6 |

| Medical complications during childbirth (T2) | |

| Yes | 28 |

| Childbirth experience (T2) | |

| Satisfactory | 58.2 |

| Difficult but satisfactory | 34.2 |

| Traumatic | 7.7 |

| Medical complications after childbirth today (T3) | |

| Yes | 12.0 |

| Instrument | Variables | Phase | M (SD) | Alpha Coefficients (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDPS | Perinatal Depression Symptoms (PeDSs) | T1 | 8.39 (5.47) | 0.86 |

| PCL-5 | Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms (P-PTSSs) | T2 | 10.84 (12.24) | 0.93 |

| EDPS | Postpartum Depression Symptoms (PoDSs) | T2 | 18.08 (9.24) | 0.88 |

| PBQ | Mother–child bonding | T3 | 13.53 (7.34) | 0.87 |

| Measurer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 0.442 ** | 1 | ||

| 3 | 0.513 * | 0.728 ** | 1 | |

| 4 | 0.497 ** | 0.608 ** | 0.629 ** | 1 |

| Independent Variable (VI) | Mediators (M) | Dependent Variable (VD) | Total Effect (e) | Direct Effect (e’) | Indirect Effect | 95% CI (Indirect Effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Perinatal Depression (PeDSs) (T1) | Posttraumatic Stress (P-PTSSs) (T2) Postpartum Depression (PeDSs) (T2) | Bonding (T3) | 0.667 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.000) | 0.281 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.961) | 0.114 (SE = 0.068) | (0.020 to 0.314) |

| Model 2 | Perinatal Depression (PeDSs) (T1) | Posttraumatic Stress (P-PTSSs) (T2) | Bonding (T3) | 0.667 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.000) | 0.281 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.961) | 0.171 (SE = 0.115) | (−0.011 to 0.462) |

| Model 3 | Perinatal Depression (PeDSs) (T1) | Postpartum Depression (PoDSs) (T2) | Bonding (T3) | 0.667 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.000) | 0.281 (SE = 0.166) (p = 0.961) | 0.098 (SE = 0.072) | (0.005 to 0.295) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vega-Sanz, M.; Berastegui, A.; Sanchez-Lopez, A. Longitudinal Influences on Maternal–Infant Bonding at 18 Months Postpartum: The Predictive Role of Perinatal and Postpartum Depression and Childbirth Trauma. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103424

Vega-Sanz M, Berastegui A, Sanchez-Lopez A. Longitudinal Influences on Maternal–Infant Bonding at 18 Months Postpartum: The Predictive Role of Perinatal and Postpartum Depression and Childbirth Trauma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103424

Chicago/Turabian StyleVega-Sanz, Maria, Ana Berastegui, and Alvaro Sanchez-Lopez. 2025. "Longitudinal Influences on Maternal–Infant Bonding at 18 Months Postpartum: The Predictive Role of Perinatal and Postpartum Depression and Childbirth Trauma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103424

APA StyleVega-Sanz, M., Berastegui, A., & Sanchez-Lopez, A. (2025). Longitudinal Influences on Maternal–Infant Bonding at 18 Months Postpartum: The Predictive Role of Perinatal and Postpartum Depression and Childbirth Trauma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103424