Thermal Imaging for Burn Wound Depth Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Setting

2.3. Thermal Imaging Camera and Imaging Procedure [10,12,15]

2.4. Study Design

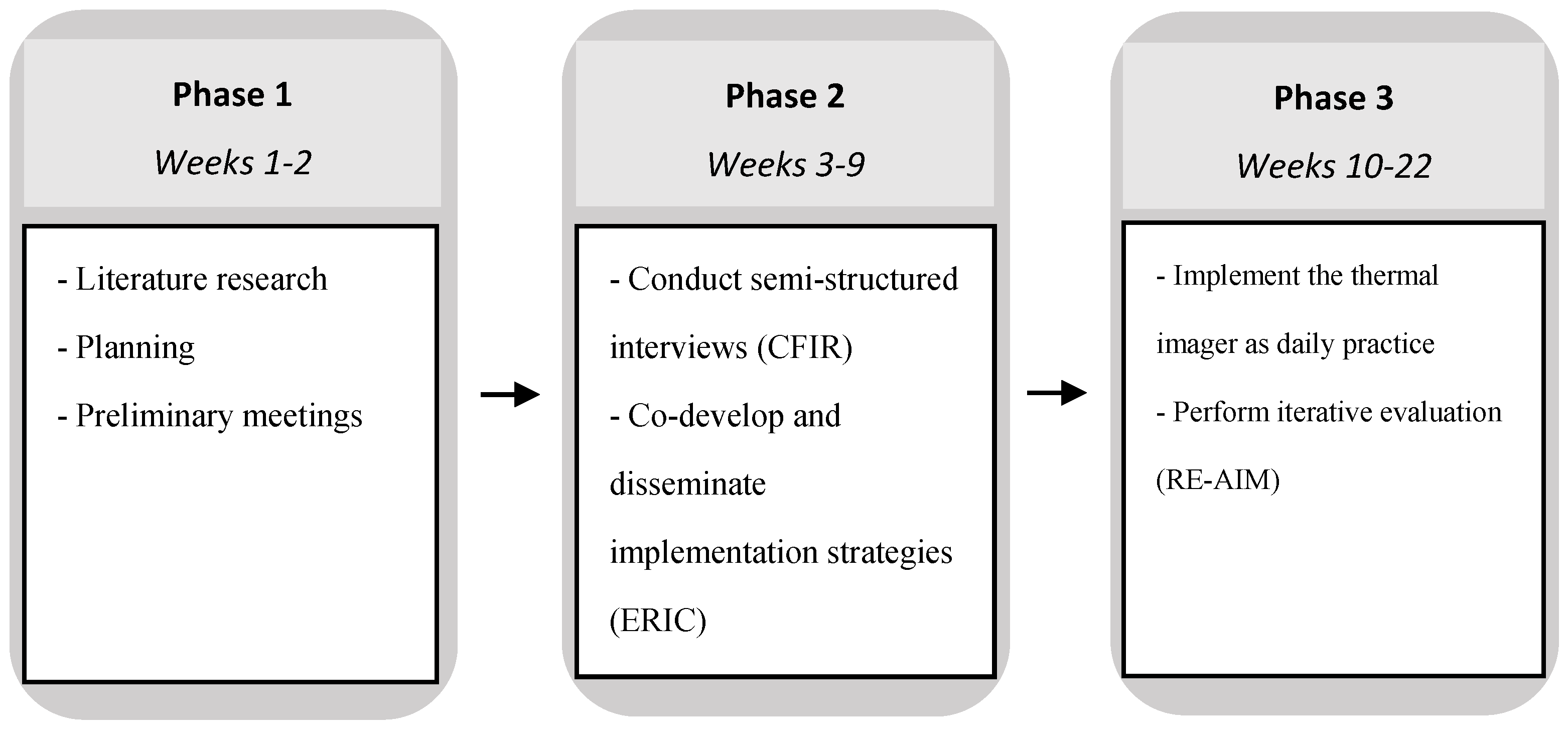

2.4.1. Phase 1: Planning

2.4.2. Phase 2: Barriers and Facilitators, Implementation Strategies

2.4.3. Phase 3: Implementation

3. Results

3.1. Barriers and Facilitators

3.2. Implementation Strategies

3.3. Evaluation of Implementation

3.3.1. First Evaluation Cycle

3.3.2. Second Evaluation Cycle

3.3.3. Long-Term Needs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definitions RE-AIM Dimensions [19]

| Reach: The absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals who are willing to participate in a given initiative, intervention, or program. Effectiveness: The impact of an intervention on important outcomes, including potential negative effects, quality of life, and economic outcomes. Adoption: The absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of settings and intervention agents (people who deliver the program) who are willing to initiate a program. Implementation: At the setting level, implementation refers to the intervention agents’ fidelity to the various elements of an intervention’s protocol, including the consistency of delivery as intended and the time and cost of the intervention. At the individual level, the implementation refers to clients’ use of the intervention strategies. Maintenance: The extent to which a program or policy becomes institutionalised or part of the routine organisational practices and policies. Within the RE-AIM framework, maintenance also applies at the individual level. At the individual level, maintenance has been defined as the long-term effects of a program on outcomes after 6 or more months after the most recent intervention contact. |

References

- Claes, K.E.; Hoeksema, H.; Robbens, C.; Verbelen, J.; Dhooghe, N.S.; De Decker, I.; Monstrey, S. The LDI Enigma, Part I: So much proof, so little use. Burns 2021, 47, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Implementation Science Overview n.d. Available online: https://impsciuw.org/implementation-science/learn/implementation-science-overview/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Topical Agents and Dressings for Local Burn Wound Care—UpToDate n.d. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/topical-agents-and-dressings-for-local-burn-wound-care?search=burns&source=search_result&selectedTitle=10~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=10 (accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Hassan, S.; Reynolds, G.; Clarkson, J.; Brooks, P. Challenging the DogmaRelationship Between Time to Healing and Formation of Hypertrophic Scars after Burn Injuries. J. Burn. Care Res. 2014, 35, e118–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimbach, D.; Engrav, L.; Grube, B.; Marvin, J. World Journal of Surgery Burn Depth: A Review. World J. Surg. 1992, 16, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeksema, H.; Van de Sijpe, K.; Tondu, T.; Hamdi, M.; Van Landuyt, K.; Blondeel, P.; Monstrey, S. Accuracy of early burn depth assessment by laser Doppler imaging on different days post burn. Burns 2009, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, S.A.; Skouras, C.A.; Byrne, P.O. An audit of the use of laser Doppler imaging (LDI) in the assessment of burns of intermediate depth. Burns 2001, 27, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspers, M.E.; van Haasterecht, L.; van Zuijlen, P.P.; Mokkink, L.B. A systematic review on the quality of measurement techniques for the assessment of burn wound depth or healing potential. Burns 2019, 45, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.; Martin, H.; Cass, D. Laser Doppler imaging prediction of burn wound outcome in children. Burns 2002, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspers, M.; Carrière, M.; Vries, A.M.-D.; Klaessens, J.; van Zuijlen, P. The FLIR ONE thermal imager for the assessment of burn wounds: Reliability and validity study. Burns 2017, 43, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, J.; Lin, M.; Tan, C.; Pham, C.H.; Huang, S.; Hulsebos, I.F.; Yenikomshian, H.; Gillenwater, J. Use of Infrared Thermography for Assessment of Burn Depth and Healing Potential: A Systematic Review. J. Burn. Care Res. 2021, 42, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, M.E.H.; Maltha, I.; Klaessens, J.H.G.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Verdaasdonk, R.M.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M. Insights into the use of thermography to assess burn wound healing potential: A reliable and valid technique when compared to laser Doppler imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016, 21, 096006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, J.; Nizamoglu, M.; Tan, A.; Gerrish, H.; Cranmer, K.; El-Muttardi, N.; Barnes, D.; Dziewulski, P. A prospective study comparing the FLIR ONE with laser Doppler imaging in the assessment of burn depth by a tertiary burns unit in the United Kingdom. Scars Burn. Heal. 2020, 6, 2059513120974261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganon, S.; Guédon, A.; Cassier, S.; Atlan, M. Contribution of thermal imaging in determining the depth of pediatric acute burns. Burns 2019, 46, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrière, M.E.; de Haas, L.E.M.; Pijpe, A.; Vries, A.M.; Gardien, K.L.M.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M.; Jaspers, M.E.H. Validity of thermography for measuring burn wound healing potential. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 28, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnock, H.; Barwick, M.; Carpenter, C.R.; Eldridge, S.; Grandes, G.; Griffiths, C.J.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Meissner, P.; Murray, E.; Patel, A.; et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ 2017, 356, i6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FLIR ONE Pro Thermal Imaging Camera for Smartphones | Teledyne FLIR n.d. Available online: https://www.flir.com/products/flir-one-pro/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualitative Data—The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research n.d. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/evaluation-design/qualitative-data/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- 2009 CFIR Constructs—The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research n.d. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/constructs-old/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Damschroder, L.J.; Lowery, J.C. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strategy Design—The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research n.d. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/choosing-strategies/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Fernández, M.E.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L.J. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.K.; Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C. Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Battaglia, C.; McCreight, M.; Ayele, R.A.; Rabin, B.A. Making Implementation Science More Rapid: Use of the RE-AIM Framework for Mid-Course Adaptations Across Five Health Services Research Projects in the Veterans Health Administration. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.C.; Halaska, C.; Sachs, P.B.; Lin, C.-T.; Sanfilippo, K.; Honce, J.M. Understanding Patient Experiences, Opinions, and Actions Taken After Viewing Their Own Radiology Images Online: Web-Based Survey. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e29496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southerland, L.T.; Hunold, K.M.; Van Fossen, J.; Caterino, J.M.; Gulker, P.; Stephens, J.A.; Bischof, J.J.; Farrell, E.; Carpenter, C.R.; Mion, L.C. An implementation science approach to geriatric screening in an emergency department. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 70, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, A.J.; Relan, P.; Beto, L.; Jones-Koliski, L.; Sandoval, S.; Clark, R.A. Infrared Thermal Imaging Has the Potential to Reduce Unnecessary Surgery and Delays to Necessary Surgery in Burn Patients. J. Burn. Care Res. 2016, 37, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, S.; Emery, J.D.; Rinaldi, J.; Kinder, J.; Bickerstaffe, A.; Saya, S.; Jenkins, M.A.; McIntosh, J. Exploring a novel method for optimising the implementation of a colorectal cancer risk prediction tool into primary care: A qualitative study. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vousden, N.; Lawley, E.; Seed, P.T.; Gidiri, M.F.; Charantimath, U.; Makonyola, G.; Brown, A.; Yadeta, L.; Best, R.; Chinkoyo, S.; et al. Exploring the effect of implementation and context on a stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial of a vital sign triage device in routine maternity care in low-resource settings. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CFIR Construct | Rating |

|---|---|

| I. Intervention Characteristics | |

| A. Innovation source | 0 |

| B. Evidence strength and quality | −2 |

| C. Relative advantage | +2 * |

| D. Adaptability | 0 |

| E. Trialability | M |

| F. Complexity | +2 * |

| G. Design quality and packaging | M |

| H. Cost | 0 |

| II. Outer Setting | |

| A. Patient needs and resources | +1 * |

| B. Cosmopolitanism | 0 |

| C. Peer pressure | X |

| D. External policies and incentives | M |

| III. Inner setting | |

| A. Structural characteristics | 0 |

| B. Networks and communications | −1 * |

| C. Culture | +2 |

| D. Implementation climate | +1 |

| 1. Tension for change | −1 * |

| 2. Compatibility | −2 * |

| 3. Relative priority | −1 * |

| 4. Organisational incentives and rewards | M |

| 5. Goals and feedback | 0 |

| 6. Learning climate | M |

| E. Readiness for implementation | −1 |

| 1. Leadership engagement | M |

| 2. Available resources | −1 |

| 3. Access to knowledge and information | −2 |

| IV. Characteristics of individuals | |

| A. Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention | −1 * |

| B. Self-efficacy | +2 * |

| C. Individual stage of change | +2 |

| D. Individual identification with organisation | M |

| E. Other personal attributes | +2 |

| V. Process | |

| A. Planning | −2 |

| B. Engaging | 0 |

| 1. Opinion leaders | M |

| 2. Formally appointed internal implementation leaders | 0 |

| 3. Champions | M |

| 4. External change agents | M |

| 5. Key stakeholders | 0 |

| 6. Innovation participants | 0 |

| C. Executing | M |

| D. Reflecting and evaluating | M |

| Intervention Characteristics | ||

| Construct | Barrier/Facilitator | Argumentation |

| Evidence strength and quality | Strong barrier |

|

| Relative advantage | Strong facilitator |

|

| Complexity | Strong facilitator |

|

| Outer Setting | ||

| Construct | Barrier/Facilitator | Argumentation |

| Needs and resources of those served by the organisation | Weak facilitator |

|

| Inner Setting | ||

| Construct | Barrier/Facilitator | Argumentation |

| Networks and communications | Weak barrier |

|

| Culture | Strong facilitator |

|

| Implementation climate | Weak facilitator |

|

| Tension for change | Weak barrier |

|

| Compatibility | Strong barrier |

|

| Relative priority | Weak barrier |

|

| Readiness for implementation | Weak barrier |

|

| Available resources | Weak barrier |

|

| Access to knowledge and information | Strong barrier |

|

| Characteristics of Individuals | ||

| Construct | Barrier/Facilitator | Argumentation |

| Knowledge and beliefs about the innovation | Weak barrier |

|

| Self-efficacy | Strong facilitator |

|

| Individual stage of change | Strong facilitator |

|

| Other personal attributes | Strong facilitator |

|

| Process | ||

| Construct | Barrier/Facilitator | Argumentation |

| Planning | Strong barrier |

|

| ERIC Strategy | To Address Barrier | Description | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Create a formal implementation blueprint |

| During the pre-implementation phase, the implementation team created a formal implementation blueprint. This blueprint contained a timeframe, milestones, and important dates (e.g., evaluation cycles), and was disseminated via email. | Participants requested additional practical information, such as a planning. |

| Promote adaptability |

| The implementation team conducted two meetings with the hospitals’ ICT specialists during the pre-implementation phase. During these meetings, they identified the usage of a shared disk as the least time-consuming way in which the thermal images can be transferred to the electronic health record (EHR), and linked to the correct patient. | Various participants indicated that the easy transferability of thermal images to the EHR is essential for successful implementation. In addition, lack of time was a prominent barrier to the implementation process. |

| Develop educational materials |

| During the pre-implementation phase, the implementation team developed and disseminated educational materials. Educational materials included the following: (1) guidelines on how to use the thermal imager, (2) an overview of evidence about the thermal imager, and (3) a reference card containing inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, ΔT cut-off values, and a step-by-step guide on how to use the device. | All participants requested practical information (e.g., how to start the device, how to obtain results, who are going to use the device, how to get results in the EHR). |

| Facilitation |

| During the implementation phase, implementation team members were present in the outpatient clinic to support the implementers. This allowed for interactive problem solving. | The quick and effective countering of emerging problems is essential, as these problems may impede the implementation process. In addition, facilitation can promote relationships between the implementation team and participants. |

| Conduct ongoing training |

| The implementation team conducted ongoing training during the implementation phase. | Conducting ongoing training enhances the implementation fidelity and speed of usage. |

| Identify early adopters |

| During the implementation phase, the implementation team identified the early adopters of the thermal imager to learn from their experiences. | Identifying early adopters can provide the implementation team with valuable information on why some participants are more successful in implementing the intervention than others. This information can be used to foster implementation amongst late adopters. |

| At 7 Weeks (Cycle 1) | At 13 Weeks (Cycle 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Reach | ||

| Number of patients that presented at the outpatient clinic (n) a | 49 | 102 |

| Number of patients presenting between days 2 and 5 postburn (n) | 17 | 35 |

| Number of patients imaged (n) | 13 | 25 |

| Proportion of patients that were imaged compared to the number of patients that presented at the outpatient clinic (%) | 26.5% | 24.5% |

| Proportion of patients that were imaged compared to the number of patient presenting between days 2 and 5 postburn (%) | 76.5% | 71.4% |

| Number of imaged burn wounds (n) | 16 | 30 |

| Effectiveness b,c | ||

| Number of correctly classified burn wounds (n) | 12 | 23 |

| Number of falsely classified burn wounds (n) | 0 | 2 |

| Number of inconclusive results (n) c | 3 | 3 |

| Healing potential unknown (n) | 1 | 2 |

| Adoption | ||

| Number of staff that used the thermal imager (n) | 4/7 | 6/7 |

| RE-AIM Dimension | Rating | At 7 Weeks (Cycle 1) | At 13 Weeks (Cycle 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | Rating on importance | 4 (3.5–5) | 4 (3–4.5) |

| Rating on satisfaction with progress | 2 (1.5–3) | 2 (2–2.5) | |

| Effectiveness | Rating on importance | 5 (4.5–5) | 5 (4–5) |

| Rating on satisfaction with progress | 3.5 (2.5–4) | 2 (2–3.5) | |

| Adoption | Rating on importance | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3.5–4.5) |

| Rating on satisfaction with progress | 2 (1.5–3.5) | 2 (1.5–2.5) | |

| Implementation | Rating on importance | 5 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| Rating on satisfaction with progress | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–2.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Haan, J.; Stoop, M.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M.; Pijpe, A. Thermal Imaging for Burn Wound Depth Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13072061

de Haan J, Stoop M, van Zuijlen PPM, Pijpe A. Thermal Imaging for Burn Wound Depth Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(7):2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13072061

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Haan, Jesse, Matthea Stoop, Paul P. M. van Zuijlen, and Anouk Pijpe. 2024. "Thermal Imaging for Burn Wound Depth Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 7: 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13072061

APA Stylede Haan, J., Stoop, M., van Zuijlen, P. P. M., & Pijpe, A. (2024). Thermal Imaging for Burn Wound Depth Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(7), 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13072061