Abstract

Background and Objectives: Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) develops when the spinal cord is damaged and leads to partial or complete loss of motor and/or sensory function, usually below the level of injury. Medical advances in the last few decades have enabled SCI patients to survive after their initial injury and extend their life expectancy. As a result, the need for outcome measures to assess health and Quality of Life (QoL) after rehabilitation is increasing. All QoL assessment measures include implicit or explicit reactions and evaluations of a person’s life characteristics. This review aims to investigate QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI and how the instruments that are used may influence rehabilitation. Materials and Methods: Studies were identified from an online search of PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases. Studies published between 2013 and 2023 were selected. This review has been registered on OSF (n) 892NY. Results: We found that different psychological and physical aspects can positively or negatively influence the QoL of SCI patients, and the measurement of this aspect, despite the number of tools, is limited due to the lack of a universal definition of this theme and the greater prevalence of quantitative rather than qualitative tools. Conclusions: This review has demonstrated that clinicians and psychologists involved in SCI rehabilitation should consider tools that use high-quality standardized outcome measures to detect and compare potential differences and outcomes of interventions related to HRQoL and their relationship with the personality and functional status of the patient.

1. Introduction

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is a complex neurological condition that causes physical dependence, psychological stress, morbidity, and economic charge. It develops when the spinal cord is damaged (e.g., by trauma) and leads to partial or complete loss of motor and/or sensory function, usually below the level of injury [1]. Over the last 30 years, the global number of cases increased from 236 to 1298 cases per million population. The global incidence of SCI is estimated to have declined to 250,000–500,000 cases per year [2]. Evidence about current treatments is still scarce and, generally, treatments can only provide support for patients with lifelong disabilities [2]. Patients with SCI can experience a range of secondary physical and psychological effects, including anxiety and depression (experienced by approximately 22.2% of the population) [3] and poor QoL [4]. Immediately after the injury, stabilization of the patient becomes the priority, and therefore the patient faces many challenges on the physical, social, environmental, and psychological levels. Institutional rehabilitation provides a largely standardized supportive environment that helps SCI patients adjust to their newly acquired disabilities. Healthcare professionals work with the patient and their relatives to prepare them for their return to everyday life [4]. Several recent studies have emphasized that QoL is not strongly influenced by physical variables [5,6]. Age [7,8] and gender [9] are also weakly associated with QoL in people with SCI. Psychological assets are strong predictors of life satisfaction and welfare. They are personal characteristics and qualities that can influence how people perceive and cope with challenges. Positive emotions [7,10], high self-efficacy [10,11], optimism [12], hope [7,10], and coherence [10,13] were shown to be positively associated with improved QoL; psychological dynamics such as appraisal and the coping strategies used by SCI patients also significantly predict QoL over time [14]. Medical advances in the last few decades have enabled SCI patients to survive after their injury and extend their life expectancy [15]. As a result, the need for outcome measures to assess health and QoL after rehabilitation is increasing [16,17]. All QoL assessment measures include implicit or explicit reactions and evaluations of a person’s life characteristics (outcomes). Therefore, the distinction between whether a measure is based on an ‘objective’ or ‘subjective’ view depends on (1) whose expectations and assessments are used and (2) which reaction and/or evaluation was made explicit [18]. Some of the tools that can be used to assess QoL in patients with SCI are the following: Satisfaction With Life Survey [19]; Sense of Well-Being Index [20]; World Health Organization Quality of Life [21]; Quality of Life Index [22]; Quality of Life Profile for Adults with Physical Disabilities [23]; Short Form 36 [24]; Short Form 12 [25]; Short Form 6-Disability [26]; Short Form 36 Veterans/SCI [27]; Sickness Impact Profile [28]; Patient-Reported Impact of Spasticity Measure [29]; Quality of Well-Being Questionnaire-SA [30]. The SCI population also includes a significant number of people with pre-existing mental health disorders (MHDs). The MHDs listed in the literature include depression, personality disorders, schizophrenia, drug and alcohol abuse, and mood disorders [31]. Two plausible rationales underlie the elevated risk of SCI among individuals with a history of MHDs. A substantial proportion of SCI cases in this demographic stem from suicide attempts, with a significant subset of these instances involving individuals diagnosed with MHDs [32]. This substantiates the correlation between the presence of MHDs and suicidal behaviors. Notably, the favored modus operandi for suicide attempts is ‘jumping,’ potentially elucidating the heightened prevalence of such attempts in individuals with schizophrenia compared to the general population. This implies that MHDs might influence the choice of suicide method, thereby increasing the likelihood of physical harm if the attempt is unsuccessful [33]. Secondarily, indirect contributors to SCI encompass compromised concentration, a heightened propensity for risk-taking behavior, and substance abuse, all of which are intricately linked with MHDs. Recognizing this specific subgroup of SCI patients is paramount, necessitating a thorough examination of their long-term prognoses and rehabilitation outcomes. The Needs Assessment Checklist, serving as a clinically valid and reliable rehabilitation assessment tool, facilitates a comparative analysis of rehabilitation outcomes between individuals with MHDs and those without [34].

Another factor to take into consideration is the type of personality, such as Type D (distressed) Personality (TDP). This is delineated as the simultaneous presence of negative affect (NA) and social inhibition (SI). Negative affect encompasses the inclination towards experiencing adverse emotions, including but not limited to anger, resentment, discomfort, worry, and depressive feelings. Social inhibition, on the other hand, involves the apprehension of potential criticism or rejection from others, coupled with challenges in expressing oneself appropriately in social contexts. Additionally, social inhibition correlates with a propensity for negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. Transdiagnostic personality dysfunction (TDP) has been documented to exhibit a strong association with both anxiety and depression, as evidenced by previous studies [35,36]. SCI patients with TDP are likely to feel intense anxiety and distress and that can induce NA. According to the literature, therefore, individual differences in psychological factors can significantly influence recovery times, functional outcomes, and physical performance in SCI. Consequently, evaluating individual requirements and delivering tailored psychological support holds the potential to enhance functional autonomy and bolster the long-term Quality of Life (QoL) of individuals grappling with SCI. Given their modifiable nature, psychological factors, encompassing coping skills, health-related behaviors, and the individual’s psychological state, should be conscientiously addressed by the healthcare professional overseeing the entirety of the rehabilitation process [37,38,39]. Functional independence has been emphasized as a factor related to QoL, as it is an important indicator of independence in daily life. The practice of regular physical activity should be seen as a tool to facilitate the reintegration of people with SCI who face physical, social, and psychological challenges by developing functional independence models. In this context, positive experiences in the various domains that make up QoL enable individuals to move on with their lives [40]. Second, physical fitness is conceptualized as specific types of physical activity that are organized and structured to promote health and develop or maintain competitive skills in sports [41]. The literature on people with SCI often focuses on the potential beneficial effects of controlled physical exercise on QoL and functional independence parameters and does not address other daily activities that may contribute to an active lifestyle [42]. Exercise is an important tool when used in people with neurological paralysis. It can improve the musculoskeletal system, neural plasticity, and functional independence, promoting a good QoL for patients with SCI and a better neurorehabilitation path. This scoping review aims to investigate the QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI and how the instruments that are used may influence rehabilitation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

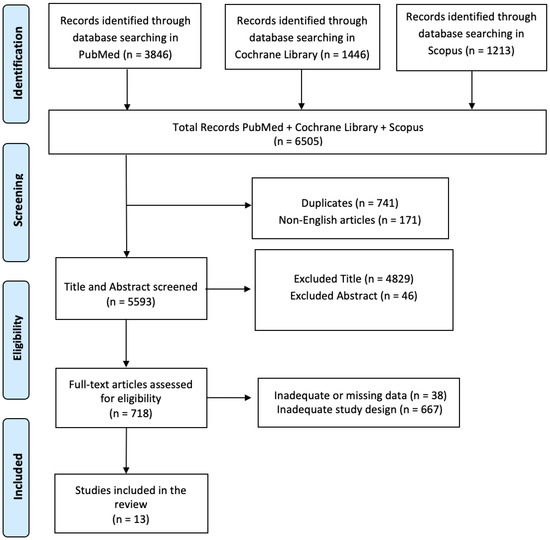

A comprehensive literature review was performed, utilizing PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Scopus. The search strategy involved querying articles using the following string: (Title/Abstract: “Spinal Cord Injury”) AND/OR (Title/Abstract: “Personality Symptoms”) AND/OR (Title/Abstract: “Neurorehabilitation”) with a 2013/2023 search time range. The PRISMA flow diagram was implemented to delineate the sequential progression of stages (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) in the compilation and evaluation of eligible studies, as depicted in Figure 1. Titles and abstracts were independently scanned and retrieved from database searches. The suitability of the article was then assessed according to the defined inclusion criteria. Ultimately, we received all titles and abstracts whose full texts met the criteria for inclusion. To mitigate the risk of bias, multiple expert teams collaborated, jointly selecting articles, independently analyzing the data, and engaging in discussions to address any disparities that arose. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. This review was registered on OSF (n) 892NY.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the current review.

2.2. PICO Evaluation

The search term combinations were defined using a population, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) model. The population was limited to patients with moderate to severe SCI; the intervention included all innovative approaches, protocols, and assessment tools used to measure and understand the psychological and contextual factors and aspects that influence QoL and rehabilitation; the comparison was evaluated considering the different tools available to measure QoL in patients with SCI, both before and during a course of psychological and motor rehabilitation; and the results included any improvements in the sensitivity of the tools used to identify the functional, motor, and psychological factors shown by patients before and after the injury.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

A study was included if it described or investigated QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI and how these instruments may influence rehabilitation. The review included only articles written in English. Studies describing or investigating the functional assessment of these patients were also included. We only included studies conducted in human populations and published in English that met the following criteria: (i) original or protocol studies of any type and (ii) articles that presented some instrument assessment and functional status information that could influence the QoL and rehabilitation of patients with an SCI diagnosis.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if there was a lack of data or a lack of information about or description of the QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI during the rehabilitation process. Systematic, narrative, or integrated reviews were also excluded, but reference lists were checked and added if necessary. All articles written in languages other than English were excluded.

2.5. Assess Quality of Included Studies—Risk of Bias

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess each study (Table 1), following the criteria of the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies Methods Working Group. The NOS was adapted to assess the methodological quality of non-randomized interventional studies. The evaluation includes key areas such as subjects’ selection, the comparability of groups, and the evaluation of outcomes. The NOS allows for a systematic assessment of potential bias, offering insights into the strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies.

Table 1.

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale results for each study involved in this review.

3. Results

A total of 6505 articles were found in the selected databases. A total of 741 articles were duplicates, and so they were excluded after screening. A total of 171 articles were removed because they were not written in English, and 4875 articles were excluded based on the title and abstract screening. Finally, 705 articles were removed based on the screening for inadequate study designs and untraceable articles (Figure 1). Thirteen research articles met the inclusion criteria, and were therefore included in this review. A survey of these studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of studies included in the research.

The articles described in this review investigated the QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI and how these instruments may influence rehabilitation. QoL and a well-being assessment of patients with SCI were analyzed in six articles [43,44,45,46,48,49]. The methods used to perform clinical evaluation of QoL and symptoms of SCI have been described in three articles [47,51,52]. The relationship between functional status, rehabilitation, and comorbidities was explained in four articles [50,53,54,55].

3.1. QoL and Assessment in Patients with SCI

The QoL and the tools available for evaluation are essential to establish an adequate rehabilitation path for patients with SCI. A summary of these tools can be found in Table 3. In one study, it was found that QoL in SCI patients can be influenced by factors such as spirituality and depression; in a sample of 210 people, approximately 26% had major depressive disorder. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapies—Spiritual, as measured by spirituality, has proven to be an important determinant of QoL [43]. A second study demonstrated that WHOQOL-BREF and PWI prescribed injury-level group classification, while WHOQOL-BREF prescribed environment group classification. Neither questionnaire differentiated between injury type. In the early post-acute phase of rehabilitation, there was no significant difference in QoL scores between tetraplegia and paraplegia, while QoL scores were significantly higher for paraplegia in the long-term environment group. In the early post-acute phase of rehabilitation, QoL was significantly higher for paraplegia than for tetraplegia [44]. A multicentered study proved that DMSE constitutes a psychological resource correlating with higher levels of participation and life satisfaction after SCI. The UW-SES-6 is a brief and simple measure of this psychological resource [45]. A prospective observational registry cohort study revealed the complex interactions and lasting effects of health conditions that negatively impact functioning, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), and life satisfaction following SCI. A worse health status was negatively correlated with worse mental health and positively correlated with lower functioning. Being married and having higher functioning had a positive effect on the Lisat-11 test, while a worse health status had a negative effect [46]. A longitudinal study proved that people with chronic SCI may be vulnerable to mental health problems even if they previously demonstrated good resilience. Furthermore, subjective well-being after SCI may not be as stable as the general QoL literature examining genetic and personality associations with subjective well-being. No statistically significant distinctions in age or duration since injury were observed between individuals reporting noteworthy emotional symptoms and those who did not. Furthermore, there was an absence of any discernible systematic alterations in health status. [48]. A cross-sectional study showed that, in a sample of 105 patients, 39% of people with SCI had TDP and the mental component of HRQoL was associated with TDP in people with SCI. Vitality, emotional role, and mental health scores were also significantly lower; TDP primarily predicted the mental health component of the SF-36; NA was a significant predictor of mental health, especially vitality and mental health; and the mental health component of the SF-36 was a significant predictor of the mental health component of HRQoL [49]. In another article, a longitudinal measurement of invariance was conducted, showing that, in terms of measurement and validation tools, the SCI-QoL-BDS represent a valid measure for assessing the QoL of people undergoing inpatient rehabilitation for their first SCI/disability. The SCI-QoL-BDS consists of three items assessing general life, physical, and mental state. The intercepts of all items, except satisfaction with physical health, are invariant over time, indicating the partial invariance of the SCI-QoL-BDS intercepts [47]. Another study showed that a multimodal pain assessment approach combining clinical examination, quantitative sensory testing, blood biomarkers, and an assessment of psychosocial factors at various time points is effective and functional in the early stages of rehabilitation after SCI. More specifically, the SCIPI questionnaire is effective in differentiating nociceptive pain from neuropathic pain, which progressively increases in severity over time [51]. One last article demonstrated that, by adding three additional items measuring arm and shoulder function to the NRS, expanding the scoring criteria to full recovery, and using the new NRS score, estimates of neuromuscular functional recovery after SCI were improved across a wide range of levels and severities.

Table 3.

The subjective measures used to assess QoL following SCI.

The NRS score improves neuromuscular recovery estimates across a wide range of SCI levels and severities and furnishes a heightened level of sensitivity and a comprehensive metric for clinical practice and research pertaining to functional recovery following SCI. The NRS score is a more comprehensive measure than other measures commonly used as endpoints for SCI rehabilitation [52].

3.2. Rehabilitation, Comorbidities, and Functional Status in SCI

The assessment of comorbidities and the functional status of the patient with SCI are two aspects that should be paid attention to during the diagnosis and before setting up a rehabilitation program. One study found that the commonly used comorbidity indicators do not reflect the extent of comorbidity in the SCI rehabilitation population. Furthermore, ICD-10 CM does not accurately capture the comorbidities that are prevalent in this population and SCI sequelae are coded with high frequency. Functional status is a better predictor of readmission than comorbidities in many inpatient rehabilitation populations, including SCI ICD coding data, but provides less information on disease severity and clinical instability. The existence of conditions influencing functional status could serve as a more reliable indicator of clinical status. Consequently, it may exhibit enhanced sensitivity in capturing patient characteristics that exert an impact on the outcomes. [50]. From a functional perspective, SEM was used to examine the possible influence of mental function on the relationship between physical structure, physical function, and activity, and structural models of depression, optimism, and self-esteem showed that pain had a significant indirect effect on independence in ADL activities. In the structural model of anxiety, group differences were found in the etiologic group. Since pain was the only physical function that had an indirect effect on independence in ADL activities in the structural model for depression, optimism, and self-esteem, it is worth re-examining the relationship between pain and these mental functions in more detail, in combination with other pain items, such as clinical pain records [53]. Another study found that, in patients with SCI undergoing initial rehabilitation, functional trajectories were categorized into four different classes. Given a sample of 748 individuals, the mean functional trajectories estimated by class were defined as stable high functioning (n = 307; 41.04%), early functional recovery (n = 39; 5.21%), moderate functional recovery (n = 287; 38.37%), and slow functional recovery (n = 115; 15.37%), in order of the identified classes. Trajectory studies of outcomes such as life satisfaction and employment status showed that independence in ADL performance, as assessed by the FIM, was a trajectory predictor for each class [54]. One last article shows that complications are more common in patients with SCI. The presence of complications negatively affects functional status at discharge and length of hospital stay, increasing the risk of institutionalization. Patients without complications had significantly better functional status at admission and discharge compared to patients with complications [55].

4. Discussion

Our review aimed to analyze the QoL and its assessment in patients with SCI and how these instruments may influence rehabilitation. The studies included in this review have demonstrated that the QoL of SCI patients can be influenced by factors such as spirituality and depression, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapies measuring spirituality were proven to be an important determinant of QoL. Furthermore, in the early post-acute phase of rehabilitation, QoL is significantly higher in paraplegia than in tetraplegia [43,44]. It has also been shown that DMSE is a psychological resource associated with greater engagement and life satisfaction after SCI, while a worse health status was negatively correlated with worse mental health and positively correlated with lower functioning. Moreover, being married and having good functioning has a positive effect on the Lisat-11 test, while a worse health status has a negative effect [45,46]. Some articles also suggest that chronic SCI patients may be more prone to mental health problems even if they were previously more resilient; the mental component of HRQoL in SCI patients was associated with TDP. In addition, TDP primarily predicted the mental health component of the SF-36, while NA is an important predictor of mental health, especially vitality and mental health [48,49]. In terms of the methodological and clinical tools used to assess QoL in these patients, the SCI-QoL-BDS was found to be a consistent and valid measure to assess this aspect in patients entering hospital rehabilitation for the first time after SCI/disability. Furthermore, a multifaceted pain assessment approach combining clinical examination, quantitative sensory testing, blood biomarkers, and an assessment of psychosocial factors at various time points is effective and functional at the early stages of rehabilitation after SCI, and the NRS score appears to improve pain prediction. Neuromuscular recovery is a more sensitive and comprehensive indicator in clinical practice and research on functional recovery after SCI due to the wide range of levels and severity [47,51,52]. Articles on rehabilitation, comorbidities, and functional capacity in these patients show that ‘ICD-10 CM fails to accurately capture comorbidities that are common in this population. Functional status is a better predictor of readmission than comorbidities in many inpatient rehabilitation populations. From a functional perspective, pain has been proven to have a significant indirect effect on independence in ADL activities. Furthermore, trajectory studies on outcomes such as life satisfaction and employment status have shown that independence in ADL performance, as assessed by the FIM, is a predictor of the trajectory of development. In addition, the presence of comorbidities harms functional status at discharge, in addition to increasing the length of stay, and increases the risk of institutionalization [50,53,54,55]. The literature shows that the majority of studies examining QoL after SCI have predominantly embraced a quantitative methodology. Researchers have employed various tools, including single-item rating scales, multi-item rating scales (addressing overall life satisfaction), and multi-item questionnaires (with items gauging satisfaction with specific aspects of life) [56]. However, the inconsistency in approaches poses challenges for obtaining a comparison and agreement across studies.

Beyond the methodological disparities, quantitative investigations into QoL encounter inherent challenges. Firstly, attempts to quantify qualitative experiences tend to blur the distinctions between quantitative and qualitative realms [57]. Additionally, the delineation of categories deemed relevant in conventional research is influenced by the choices of “experts” [58,59], inherently reflecting their values and cultural context [60,61]. Such choices are not truly “neutral” [62] or “objective” [60].

Fundamentally, the complexity of assessing QoL arises from the challenge of comprehending a life distinct from one’s own and determining the value attributed to that life. The scientific literature indicates that individuals with high tetraplegia exhibit suboptimal performance on scales employing objective factors to measure QoL. Instead, the subjective experience of life emerges as more pivotal than external expressions.

Understanding this subjective experience requires research methods that can explore both the content and context of life [63]. The scientific literature presents a significant association between QoL and gender, education level, injury classification, level of injury, and the presence of pain or pressure on the injury. People with incomplete injuries and paraplegia have been reported to have better self-care skills compared to those with complete injuries, tetraplegia, and quadriplegia. This may lead to an improved QoL as they are not completely dependent on caregivers. Similarly, higher levels of injury and lower QoL are observed in people with complete injuries. Furthermore, people with pressure ulcers have a lower QoL due to prolonged bed rest, leading to physical, social, psychological, and environmental life limitations [64]. From the perspective of personality and possible protective factors against a worse QoL, physical and positive behavior exercises are observed to have an effect. Several psychological tests have shown that wheelchair athletes have higher levels of self-satisfaction, a stronger self-image, less suicidality, and greater independence than relatively less physically active people with an SCI [65,66,67]. Research proved that the majority of SCIs are secondary to trauma and approximately 85% of cases occur in men. Therefore, men who develop an SCI as a result of trauma may share some specific personality traits. In general, the data suggest that men with an SCI tend to be pragmatic and physically oriented, have difficulty communicating their thoughts and feelings, solve abstract problems, and dislike activities that require intense interpersonal interaction. In middle age, they tend to continue to seek stimulation, remain interested in physically challenging and adventurous activities, and become less intellectually curious, persistent, and achievement-oriented [68]. They prefer to work outdoors, with objects (tools and machines), rather than with ideas and people. Other data suggest that people in this group are visual and kinesthetic learners and prefer to learn by exploring in an actively challenging environment [69]. They tend to avoid physical closeness and can be distant from other individuals. Their personality traits do not simply reflect their youthful adventurousness but rather are enduring characteristics. A tendency to use an evasive and impulsive approach to problem-solving is observed more often [70]. Some of the differences observed between men with SCI and the normative population may reflect their pre-injury personality. Some SCI patients are ambivalent about counseling or meeting with mental health providers. Young men in particular may need introspection and may not fit with traditional psychological approaches that emphasize verbal interaction [71]. Regarding the rehabilitation aspect, there are many psychological interventions, including psychotherapy, that can be used to support optimal functioning and QoL in SCI patients. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy includes interventions to improve beliefs, attitudes, and thought patterns that support positive emotions and are compatible with adaptive functioning. Cognitive restructuring helps patients to identify overly negative and distorted thought patterns and formulate and focus on more realistic and productive thought processes. Cognitive restructuring strategies are effective in reducing the cognitive distortions of catastrophizing views and associated anxiety and increasing self-efficacy [72]. There are also motivational interviewing techniques that increase people’s intrinsic motivation to make positive changes by helping patients identify desired outcomes, highlighting discrepancies between current behavior and the behavior needed to achieve the desired outcomes, and building their confidence so that they believe change is possible. Specific strategies include using active listening to build a rapport, facilitating the clarification of goals, guiding the person to expand the range of perceived options for achieving those goals, eliciting commitment to change, and affirming positive movement in that direction [73,74,75].

This scoping review had several strengths. It is based on evidence from longitudinal observational populations and cross-sectional studies with large sample sizes. It includes an analysis of the instrument used for the assessment of QoL in SCI patients. We also identified data gaps in many areas, hopefully providing information for future research. The main limitation of the present study is the few papers that meet the inclusion criteria, as we included only thirteen articles that explored QoL and its evaluation in patients with SCI and only four of them focused on the relationship between functional status, rehabilitation, and comorbidities. This, besides the heterogenous methodology and samples, prevents us from gathering robust evidence on this important topic. Three databases were also used, and the articles were restricted by date, so it is possible that important evidence was omitted. It is necessary to conduct studies on these patients to evaluate the QoL of the family and the patients regarding their experience with the disease and impairment. There is also a need for the development of a standardized qualitative tool that assesses QoL in patients with SCI to better understand their psychological needs. There are several promising tools for measuring QoL. Unfortunately, due to the lack of consistent findings and definitions, knowledge about QoL in people with SCI is still limited. In this review, we attempt to make comparisons between different QoL measures, and it should be noted that we are trying to compare different QoL measures based on different definitions. Further research is needed on the universal definition of this topic and the relevance and impact of different aspects of the lives of people with SCI regarding QoL.

In conclusion, this review shows that various psychological and physical elements can positively or negatively affect the QoL of people with SCI, that there is no universal definition of this issue, despite several available assessment tools, and that the prevalence of quantitative tools over qualitative ones limits the measurement of this element. The methodological aspects of QoL research on patients with SCI need to be improved. Many scientists and clinicians developed their scales during their research. It is important to use scales with proven reliability and validity. If a new scale is developed for a specific study, its psychometric properties need to be determined and tested. It is important to use high-quality, standardized outcome measures to detect and compare the results of interventions. Given the few studies included in our work, the conclusions that can be drawn are preliminary and the current evidence requires further investigation. Clinicians and psychologists taking part in SCI rehabilitation should consider potential differences regarding dissimilar personality traits and HRQoL. Further studies that develop and apply psychological interventions and follow person-specific goals could be of use, as well as more studies on the pre-morbid personality of these patients.

Funding

This study was supported by Current Research Funds 2024, Ministry of Health, Italy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- American Spinal Injury Association. 2015. Available online: http://www.asia-spinalinjury.org (accessed on 9 October 2018).

- Khorasanizadeh, M.; Yousefifard, M.; Eskian, M.; Lu, Y.; Chalangari, M.; Harrop, J.S.; Jazayeri, S.B.; Seyedpour, S.; Khodaei, B.; Hosseini, M.; et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2019, 30, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Murray, A. Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lude, P.; Kennedy, P.; Elfström, M.; Ballert, C. Quality of life in and after spinal cord injury rehabilitation: A longitudinal multicenter study. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2014, 20, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Tran, Y.; Craig, A. Relationship between quality of life and self-efficacy in persons with spinal cord injuries. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidal, I.B.; Veenstra, M.; Hjeltnes, N.; Biering-Sørensen, F. Health-related quality of life in persons with long-standing spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008, 46, 710–715, Erratum in Spinal Cord 2008, 46, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortte, K.B.; Gilbert, M.; Gorman, P.; Wegener, S.T. Positive psychological variables in the prediction of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2010, 55, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyh, S.; Ballert, C.; Sinnott, A.; Charlifue, S.; Catz, A.; Greve, J.M.D.; Post, M.W.M. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A comparison across six countries. Spinal Cord 2013, 51, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.C.; Goo, H.R.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, S.Y. Depression and Quality of Life in Patients within the First 6 Months after the Spinal Cord Injury. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 36, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, C.M.; Post, M.W.; van Asbeck, F.W.; Bongers-Janssen, H.M.; van der Woude, L.H.; de Groot, S.; Lindeman, E. Life satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury during the first five years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.; Tran, Y.; Middleton, J. Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2009, 47, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortenson, W.B.; Noreau, L.; Miller, W.C. The relationship between and predictors of quality of life after spinal cord injury at 3 and 15 months after discharge. Spinal Cord 2010, 48, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Lude, P.; Elfström, M.L.; Smithson, E. Sense of coherence and psychological outcomes in people with spinal cord injury: Appraisals and behavioural responses. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15 Pt 3, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, P.; Lude, P.; Elfström, M.L.; Smithson, E. Appraisals, coping and adjustment pre and post SCI rehabilitation: A 2-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord 2012, 50, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, P.J. Survival after spinal cord injury in Australia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Fouts, B.S.; Romeis, J.C.; Brownson, C.A. Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injured population. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, M.H.; Miller, S.M.; Ferrin, J.M.; Chan, F.; Rubin, E.S. Psychometric validation of a subjective well-being measure for people with spinal cord injuries. Disabil. Rehabil. 2004, 26, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkers, M.P. Individualization in quality of life measurement: Instruments and approaches. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84 (Suppl. S2), S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirzyte, A.; Perminas, A.; Biliuniene, E. Psychometric Properties of Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) in the Lithuanian Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.R.; the SCIRE Research Team; Noonan, V.K.; Sakakibara, B.M.; Miller, W.C. Quality of life instruments and definitions in individuals with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2010, 48, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A.; WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, G.; Durna, Z.; Aydiner, A. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Quality of Life Index [QLI] (Cancer version). Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, L.d.O.; de Lima, A.; Sprizon, G.S.; Ilha, J. Measurement properties of assessment instruments of quality of life in people with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2023, 47, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lins, L.; Carvalho, F.M. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Han, Y.; Zhao, F.-L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, H. Validation and comparison of EuroQoL-5 dimension (EQ-5D) and Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) among stable angina patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Saadat, S.; Javadi, M.; Divshali, B.S.; Tavakoli, A.H.; Ghodsi, S.M.; Montazeri, A.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Health-related quality of life among individuals with long-standing spinal cord injury: A comparative study of veterans and non-veterans. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A.; Diederiks, J.; de Witte, L.; Stevens, F.; Philipsen, H. Assessing the responsiveness of a functional status measure: The Sickness Impact Profile versus the SIP68. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.F.; Teal, C.R.; Engebretson, J.C.; Hart, K.A.; Mahoney, J.S.; Robinson-Whelen, S.; Sherwood, A.M. Development and validation of Patient Reported Impact of Spasticity Measure (PRISM). J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2007, 44, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool-Anwar, S.; Omobomi, O.; Quan, S. The effect of CPAP on HRQOL as measured by the Quality of Well-Being Self -Administered Questionaire (QWB-SA). Southwest J. Pulm. Crit. Care 2020, 20, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, E.R.; Soden, R.; Bartrop, R.; Mikk, M.; Taylor, T.K.F. Spinal cord and related injuries after attempted suicide: Psychiatric diagnosis and long-term follow-up. Spinal Cord 2007, 45, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harris, E.C.; Barraclough, B.M.; Grundy, D.J.; Bamford, E.S.; Inskip, H.M. Attempted suicide and completed suicide in traumatic spinal cord injury. Case reports. Spinal Cord 1996, 34, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kennedy, P.; Rogers, B.; Speer, S.; Frankel, H. Spinal cord injuries and attempted suicide: A retrospective review. Spinal Cord 1999, 37, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.N.; Rothmann, T.L.; Vogler, J.E.; Spaulding, W.D. Evaluating outcomes of rehabilitation for severe mental illness. Rehabil. Psychol. 2005, 50, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubayova, T.; Krokavcova, M.; Nagyova, I.; Rosenberger, J.; Gdovinova, Z.; Middel, B.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Type D, anxiety and depression in association with quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease and patients with multiple sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, Y.; Suzuki, E.; Iwase, T.; Doi, H.; Takao, S. Type D personality is associated with psychological distress and poor self-rated health among the elderly: A population-based study in Japan. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Lude, P.; Elfström, M.L.; Smithson, E.F. Psychological contributions to functional independence: A longitudinal investigation of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikula, P.; Nagyova, I.; Krokavcova, M.; Vitkova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; Szilasiova, J.; Gdovinova, Z.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Do coping strategies mediate the association between Type D personality and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis? J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, D.; Izawa, A.; Matsunaga, Y. The Association of Depression with Type D Personality and Coping Strategies in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, C.Y.; Greguol, M. Physical activity, quality of life, and functional autonomy of adults with spinal cord injuries. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2013, 30, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devillard, X.; Rimaud, D.; Roche, F.; Calmels, P. Effects of training programs for spinal cord injury. Ann. Réadapt. Méd. Phys. 2007, 50, 490–498, (In English and French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.S.; Forchheimer, M.; Heinemann, A.W.; Warren, A.M.; McCullumsmith, C. Assessment of the relationship of spiritual well-being to depression and quality of life for persons with spinal cord injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwecker, M.; Heled, E.; Bluvstein, V.; Catz, A.; Bloch, A.; Zeilig, G. Assessment of the unmediated relationship between neurological impairment and health-related quality of life following spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cijsouw, A.; Adriaansen, J.J.; Tepper, M.; Dijksta, C.A.; Van Linden, S.; De Groot, S.; Post, M.W.M. Associations between disability-management self-efficacy, participation and life satisfaction in people with long-standing spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, C.S.; Fallah, N.; Noonan, V.K.; Whitehurst, D.G.; Schwartz, C.E.; Finkelstein, J.A.; Craven, B.C.; Ethans, K.; O’Connell, C.; Truchon, B.C.; et al. Health Conditions: Effect on Function, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Life Satisfaction After Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. A Prospective Observational Registry Cohort Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, S.; Carrard, V.; Aparicio, M.G.; Scheel-Sailer, A.; Fekete, C.; Lude, P.; Post, M.W.M.; Westphal, M. Longitudinal measurement invariance of the international spinal cord injury quality of life basic data set (SCI-QoL-BDS) during spinal cord injury/disorder inpatient rehabilitation. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, C.; Callaway, L.; New, P. Preliminary investigation into subjective well-being, mental health, resilience, and spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2013, 36, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, S.; Solak, S.; Dündar, Ü. The association of Type D personality with functional outcomes, quality of life and neuropathic pain in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Siddiqui, S.; Slocum, C.S.; Goldstein, R.; Zafonte, R.D.; Schneider, J.C. Assessing the Ability of Comorbidity Indexes to Capture Comorbid Disease in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Spinal Cord Injury Population. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capossela, S.; Landmann, G.; Ernst, M.; Stockinger, L.; Stoyanov, J. Assessing the Feasibility of a Multimodal Approach to Pain Evaluation in Early Stages after Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S.J.; Shogren, C.; Ardolino, E.; Lorenz, D.J. Assessment of Functional Improvement without Compensation for Human Spinal Cord Injury: Extending the Neuromuscular Recovery Scale to the Upper Extremities. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodel, J.; Ehrmann, C.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J.E.; Prodinger, B.; the SwiSCI Study Group. Examining the complexity of functioning in persons with spinal cord injury attending first rehabilitation in Switzerland using structural equation modelling. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 570–580, Erratum in Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodel, J.; Ehrmann, C.; Scheel-Sailer, A.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J.E.; Prodinger, B. Identification of Classes of Functioning Trajectories and Their Predictors in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury Attending Initial Rehabilitation in Switzerland. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2021, 3, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scivoletto, G.; Marcella, M.; Floriana, P.; Federica, T.; Marco, M. Impact of complications at admission to rehabilitation on the functional status of patients with spinal cord lesion. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.; Van Dijk, A.J.; Van Asbeck, F.W.; Schrijvers, A.J. Life satisfaction of persons with spinal cord injury compared to a population group. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1998, 30, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.P. Reporting of “quality of life”: A systematic review and quantitative analysis of research publications in palliative care journals. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, M.; Nissim, E.N.; Wood, K.; Hwang, K.; Tulsky, D. Objective and subjective handicap following spinal cord injury: Interrelationships and predictors. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2002, 25, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.M.; Feinstein, A.R. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994, 272, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkers, M. Measuring quality of life: Methodological issues. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 78, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, B.; Manigandan, C.; Macaden, A.; Tharion, G.; Bhattacharji, S. Re-examining the psychology of spinal cord injury: A meaning centered approach from a cultural perspective. Spinal Cord 2001, 39, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najman, J.M.; Levine, S. Evaluating the impact of medical care and technologies on the quality of life: A review and critique. Soc. Sci. Med. Part F Med. Soc. Ethics 1981, 15, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P. Tetraplegics and the justice of resource allocation. Paraplegia 1993, 31, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kennedy, P.; Rogers, B. Reported quality of life of people with spinal cord injuries: A longitudinal analysis of the first 6 months post-discharge. Spinal Cord 2000, 38, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakamura, Y. Working ability of the paraplegics. Spinal Cord 1973, 11, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, G.; Shephard, R.J. Personality profiles of disabled individuals in relation to physical activity patterns. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1982, 22, 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R.W. Sport for the spinal paralysed person. Paraplegia 1987, 25, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rohe, D.E.; Athelstan, G.T. Vocational interests of persons with spinal cord injury. J. Couns. Psychol. 1982, 29, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollar, D.J.; Ericson, G.D. Factors Affecting Learning among Spinal Cord Injured Patients. In Proceedings of the 96th Annual Meeting, American Psychological Association, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14 August 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Elliott, T.R.; Rivera, P. Resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled personality prototypes among persons with spinal cord injury. J. Pers. Assess. 2007, 89, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, D.E.; Krause, J. Stability of interests after severe physical disability: An 11-year longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 52, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, B.E.; Pence, L.B.; Ward, L.C.; Kilgo, G.; Clements, K.L.; Cross, T.H.; Davis, A.M.; Tsui, P.W. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J. Pain 2007, 8, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkowitz, H.; Burke, B.L. Motivational interviewing as an integrative framework for the treatment of depression. In Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems; Arkowitz, H., Westra, H.A., Miller, W.R., Rollnick, S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 145–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R.; Butler, C.C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schoo, A. Motivational interviewing in the prevention and management of chronic disease: Improving physical activity and exercise in line with choice theory. Int. J. Real. Ther. 2008, 27, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).