Implementation of Kidney Biopsy in One of the Poorest Countries in the World: Experience from Zinder Hospital (Niger)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- ➢

- Study population: This study included all patients admitted to the Nephrology-Hemodialysis Department for whom an indication of kidney biopsy was made during the study period.

- ➢

- Inclusion criteria: All patients who underwent a biopsy of the native kidney at HNZ during the specified period were included.

- ➢

- Exclusion criteria: Patients who had a kidney biopsy performed at the time of nephrectomy for tumor-related reasons were not included. We recorded the following information: sociodemographic, clinical, and paraclinical data of the patients, complications observed after kidney biopsy, and histological results.

- ➢

- Kidney biopsies: Kidney ultrasound assessment was carried out just prior to the kidney biopsy in more than 50% of patients due to financial constraints. All kidney biopsies were percutaneous and performed using a BARD-type automatic gun with a single-use 16-gauge needle. Two tissue fragments were obtained—one for optical microscopy and one for immunofluorescence. The kidney biopsy cores were transported by land to Kano, Nigeria, through Maimoujia, a border town, to the Ultramedikx Pathology Laboratory. There, they were processed and then analyzed by a nephropathologist, Professor Atanda. After a delay of 72 to 96 hours, he sent us the report via email, which also included two to three photographs of the most demonstrative slides. All associated costs, including the biopsy procedure, transportation, histological examination, immunofluorescence staining, and the report from the nephropathologist, were borne by the patient, totalling CFA 135,000 or approximately EUR 206.

- ➢

- Patient classification: The main syndromes were defined as follows:

- Statistical analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iversen, P.; Brun, C. Biopsy aspiration of the kidney. Am. J. Med. 1951, 11, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korbet, S.M. Percutaneous renal biopsy. Semin. Nephrol. 2002, 22, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, D.M.; Schwartz, M.M.; Korbet, S.M. Percutaneous renal biopsy with the use of real-time ultrasound. Am. J. Nephrol. 1991, 11, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorffner, R.; Thurnher, S.; Prokesch, R.; Bankier, A.; Turetschek, K.; Schmidt, A.; Lammer, J. Embolization of iatrogenic vascular injuries of renal transplants: Immediate and follow-up results. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 1998, 21, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittier, W.L.; Korbet, S.M. Timing of complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niang, A.; Ka, E.F.; Dia, D.; Pouye, A.; Kane, A.; Dieng, M.T.; Ka, M.M.; Diouf, B.; Ndiaye, B.; Moreira-Diop, T. Lupus nephritis in Senegal: A study of 42 cases. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2008, 19, 470–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdu, A.; Atanda, A.; Bala, S.M.; Ademola, B.; Nalado, A.; Obiagwu, P.; Duarte, R.; Naicker, S. Histopathological Pattern of Kidney Diseases Among HIV-Infected Treatment-Naïve Patients in Kano, Nigeria. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2021, 14, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanefo, N.R.; Igbokwe, O.O.; Iloh, O.N.; Chikani, U.N.; Bisi-Onyemaechi, A.I.; Muoneke, V.U.; Okafor, H.U.; Uwaezuoke, S.N.; Odetunde, O.I. Percutaneous kidney biopsy and the histopathologic patterns of kidney diseases in children: An observational descriptive study at a South-East Nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, B. Renal Biopsy in the Agadir Region: Indications and Results in the Military Hospital from Agadir. Ph.D. Thesis, CADI AYYAD University of Marrakech, Marrakesh, Morocco, 2018; 159p. [Google Scholar]

- Traore, H.; Maiza, H.; Emal, V.; Dueymes, J.M. Renal biopsy: Indications, complications and results from 243 renal biopsies. Nephrol. Ther. 2015, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, M.; Hamouda, M.; Letaief, S.; Ayed, S.; Ben Saleh, M.; Handous, I.; Letaief, A.; Jaafer, I.; Aloui, S.; Skhiri, H. Biopsie rénale: Indications et résultats: À propos de 430 cas. Nephrol. Ther. 2020, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Biopsy in the Military Hospital of Morocco: Complications and Histopathological Findings—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26354589/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- N’Dah, K.J.; Tia, W.M.; Lagou, D.A.; Guei, M.C.; Abouna, A.D.; Touré, I.; Oka, K.H.; Kobenan, A.; Diopo, S.; Delma, S.; et al. Kidney biopsy in subsaharan Africa. Nephrol. Ther. 2023, 19, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niger Demography. Wikipedia. 2023. Available online: https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Niger&oldid=207122979 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Demography Mali—Wikipedia. Available online: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mali (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Demography of Morocco. Wikipedia. 2023. Available online: https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=D%C3%A9mographie_du_Maroc&oldid=206165059 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Demography of Tunisia. Wikipedia. 2023. Available online: https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=D%C3%A9mographie_de_la_Tunisie&oldid=204826158 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Rabant, M.; Snanoudj, R.; Krug, P.; Martinez, F. Method and Technique of Kidney Biopsy. In Treatise on Nephrology; E Thervet: Paris, France, 2017; p. 734. [Google Scholar]

- Kéita, Y.; Dial, C.; Ka, E.F.; Sylla, A.; Cissé, M.M.; Ndongo, A.A.; Seck, S.M.; Ba, A.; Thiongane, A.; Lemrabott, A.T.; et al. Analyse de la biopsie renale chez l’enfant a l’Hopital Aristide le Dantec de Dakar. Afr. J. Paediatr. Nephrol. 2015, 2, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mbarki, H.; Belghiti, K.A.; Harmouch, T.; Najdi, A.; Arrayhani, M.; Sqalli, T. Renal needle biopsy in the Department of Nephrology in Fèz: Indications and results: About 522 cases. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mhamedi, S.A.; Hicham, M.; Mohammed, B.; Yassamine, B.; Intissar, H. Renal needle biopsy: Indications, complications and results. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 31, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touiti, N.; Houssaini, T.S.; Iken, I.; Benslimane, A.; Achour, S. Prevalence of herbal medicine use among patients with kidney disease: A cross-sectional study from Morocco. Nephrol. Ther. 2020, 16, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, F.F.; Meto, D.T.; Halle, M.P.; Ngogang, J.; Kengne, A.P. Prevalence and determinants of chronic kidney disease in rural and urban Cameroonians: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannor, E.K.; Sarfo, F.S.; Mobula, L.M.; Sarfo-Kantanka, O.; Adu-Gyamfi, R.; Plange-Rhule, J. Prevalence and predictors of chronic kidney disease among Ghanaian patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019, 21, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjami, D.; Baghdali, B.F.; Boudalia, B.H.; Brazi, B.N.; Marouki, M.Z.; Kouachi, K.C.; Bourkab, B.I.; Taouti, T.S.; Bounjaoui, B.Z.; Haddoum, F.H. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and herbal medicine: How did Senna Makki succeed in “crashing” the kidneys? About a case. Nephrol. Ther. 2021, 17, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahoui, S.; Vigan, J.; Agboton, B.L.; Dovonou, C.A.; Alassani, C.A.; Adjalla, W.K.; Eteka, E.; Djima, H.; Houet, N. Lifestyle factors and acute renal failure at the Departmental University Hospital Center- Borgou (Benin). Rev. Int. Sc. Med. Abj. 2021, 23, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur, C.; Nochy, D.; Bariety, J. Renal biopsy: Sampling techniques, contra indications, complications. Ther. Nephrol. 2009, 5, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebiosu, C.O.; Kadiri, S. Percutaneous renal biopsy as an outpatient procedure. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2004, 96, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Obiagwu, P.N.; Abdu, A.; Atanda, A.T. Out-patient percutaneous renal biopsy among children in Northern Nigeria: A single center experience. Ann. Afr. Med. 2014, 13, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajawo, S.; Ekrikpo, U.; Moloi, M.W.; Noubiap, J.J.; Osman, M.A.; Okpechi-Samuel, U.S.; Kengne, A.P.; Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G. A Systematic Review of Complications Associated with Percutaneous Native Kidney Biopsies in Adults in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 6, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- En−Niya, F.; Bouattar, T.; Hajar, B.; Hind, J.; Pierre, D.J.; Benamar, L.; Alhamany, Z.; Bayahia, R.; Ouzeddoune, N. Renal biopsy: Indications and results from 549 renal biopsies. Nephrol. Ther. 2017, 13, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diawara, A.; Coulibaly, D.M.; Hussain, T.Y.A.; Cisse, C.; Li, J.; Wele, M.; Diakite, M.; Traore, K.; Doumbia, S.O.; Shaffer, J.G. Type 2 diabetes prevalence, awareness, and risk factors in rural Mali: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpor, E.; Akyirem, S.; Adade Duodu, P. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight and obesity among persons with type 2 diabetes in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2023, 55, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrib, A.; Njim, T.; Adeyemi, O.; Moyo, F.; Halloran, N.; Luo, H.; Wang, D.; Okebe, J.; Bates, K.; Santos, V.S.; et al. Retention in care for type 2 diabetes management in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2023, 28, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR); mL/min | Number of Patients | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| ≥90 | 29 | 24.2 |

| [60–89] | 14 | 11.6 |

| [30–59] | 13 | 10.8 |

| [15–29] | 11 | 9.2 |

| <15 | 53 | 44.2 |

| Total | 120 | 100.0 |

| 24-h Proteinuria | Number of Patients | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| Abundant | 56 | 46.7 |

| Minimal | 15 | 12.5 |

| Average | 49 | 40.8 |

| Total | 120 | 100.0 |

| Indication of KB | Number of Cases | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| Unexplained Hematuria | 1 | 0.83 |

| Unexplained Chronic Kidney Failure | 35 | 29.17 |

| Lupus | 6 | 5.0 |

| Massive Non-Nephrotic Proteinuria | 1 | 0.83 |

| Scabiosis | 2 | 1.67 |

| Glomerular Syndrome | 15 | 12.5 |

| Nephrotic Syndrome | 60 | 50.0 |

| Total | 120 | 100.0 |

| Acute kidney injury (with some of the above symptoms) | 12 | 10 |

| Type of Complications | Number of Cases | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| Gross hematuria | 15 | 71.4 |

| Microscopic Hematuria | 6 | 28.6 |

| Total | 21 | 100.0 |

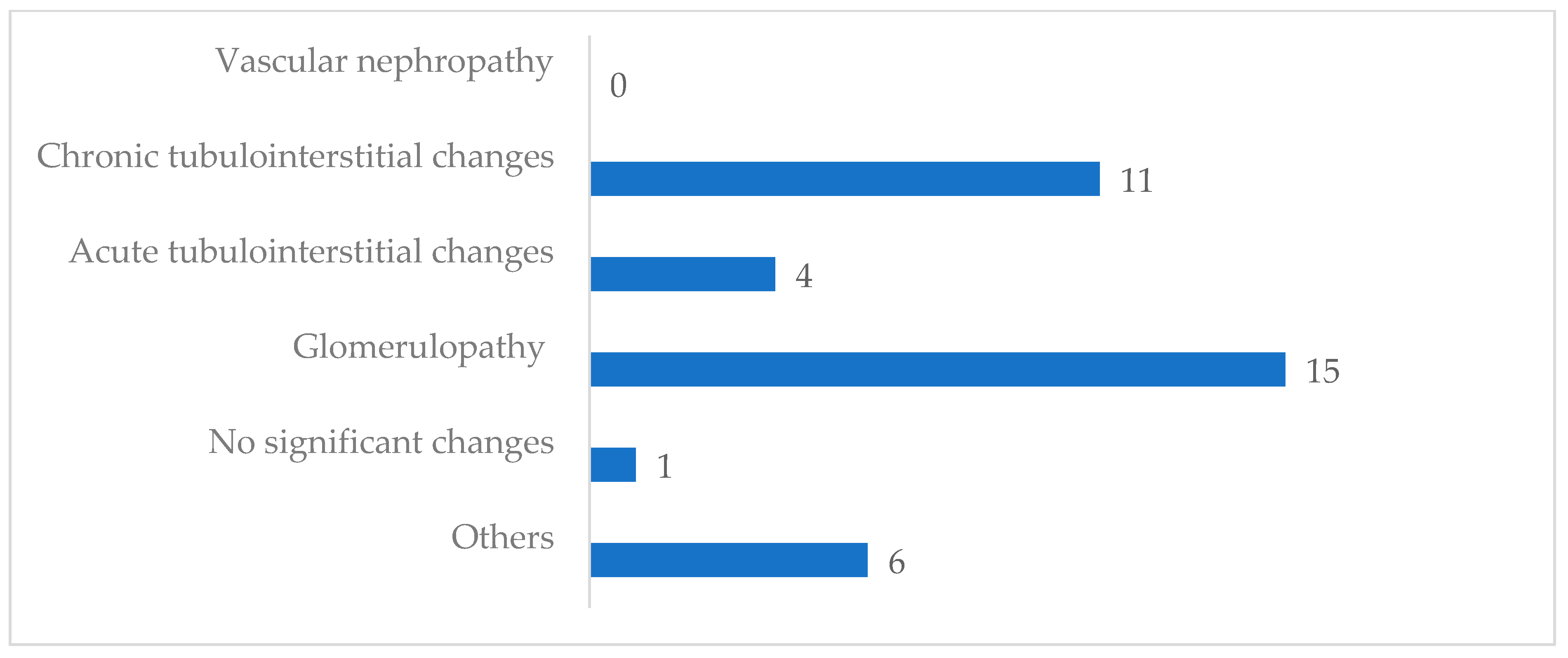

| Types of Lesions | Number of Patients | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Change Disease | 9 | 8.0 |

| Focal And Segmental Glomerulosclerosis | 12 | 10.6 |

| Membranous Glomerulonephritis | 3 | 2.7 |

| Diffuse Glomerulosclerosis | 10 | 8.8 |

| Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis | 15 | 13.3 |

| Iga Nephropathy | 1 | 0.9 |

| Lupus Nephropathy | 10 | 8.8 |

| Diabetic Nephropathy | 3 | 2.7 |

| Vascular Nephropathy | 8 | 7.1 |

| Chronic Tubulointerstitial Nephritis | 22 | 19.5 |

| Acute Tubular Necrosis | 7 | 6.2 |

| Acute Tubulointerstitial Nephritis | 1 | 0.9 |

| Acute Interstitial Nephritis | 2 | 1.8 |

| Burkitt’sLymphoma | 1 | 0.9 |

| Chronic Pyelonephritis | 2 | 1.8 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 1 | 0.9 |

| Post-Infectious Glomerunephritis | 2 | 1.8 |

| Nodular Glomerulosclerosis | 1 | 0.9 |

| No Damage | 3 | 2.7 |

| Total | 113 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diongolé, H.M.; Tondi, Z.M.M.; Garba, A.; Ganiou, K.; Chaibou, L.; Bonkano, D.; Aboubacar, I.; Seribah, A.A.; Abdoulaye Idrissa, A.M.; Atanda, A.; et al. Implementation of Kidney Biopsy in One of the Poorest Countries in the World: Experience from Zinder Hospital (Niger). J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13030664

Diongolé HM, Tondi ZMM, Garba A, Ganiou K, Chaibou L, Bonkano D, Aboubacar I, Seribah AA, Abdoulaye Idrissa AM, Atanda A, et al. Implementation of Kidney Biopsy in One of the Poorest Countries in the World: Experience from Zinder Hospital (Niger). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(3):664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13030664

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiongolé, Hassane Moussa, Zeinabou Maiga Moussa Tondi, Abdoulazize Garba, Kabirou Ganiou, Laouali Chaibou, Djibrilla Bonkano, Illiassou Aboubacar, Abdoul Aziz Seribah, Abdoul Madjid Abdoulaye Idrissa, Akinfenwa Atanda, and et al. 2024. "Implementation of Kidney Biopsy in One of the Poorest Countries in the World: Experience from Zinder Hospital (Niger)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 3: 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13030664

APA StyleDiongolé, H. M., Tondi, Z. M. M., Garba, A., Ganiou, K., Chaibou, L., Bonkano, D., Aboubacar, I., Seribah, A. A., Abdoulaye Idrissa, A. M., Atanda, A., & Rostaing, L. (2024). Implementation of Kidney Biopsy in One of the Poorest Countries in the World: Experience from Zinder Hospital (Niger). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(3), 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13030664