Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Women with Endometriosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

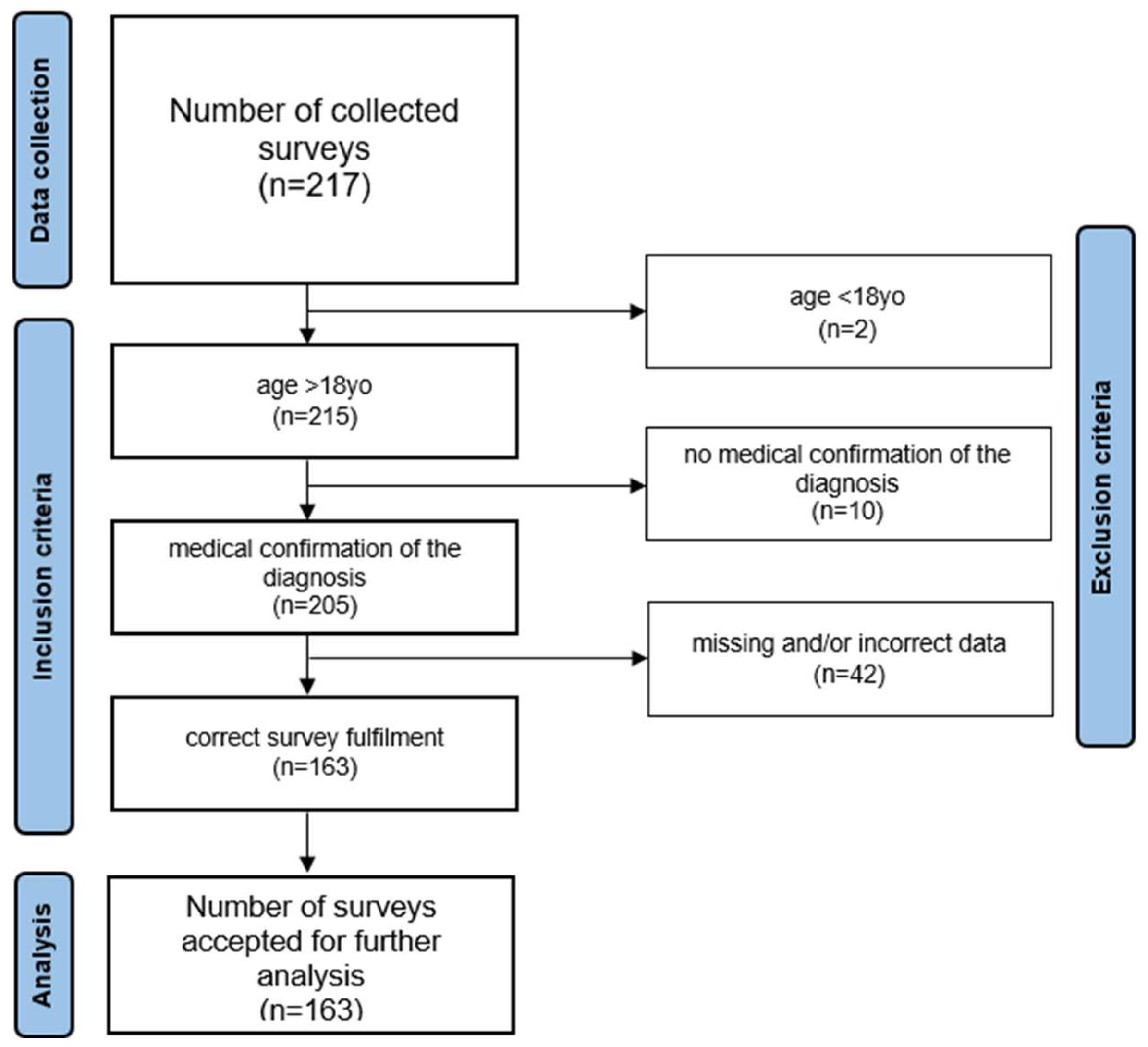

2.1. Material

2.2. Methods

- When did your first symptoms of endometriosis appear? Provide the date (month and year).

- How long after the first symptoms of endometriosis appeared did you go to the doctor? Provide the date (month and year).

- How long after your first medical consultation did you receive a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis? Provide the date (month and year).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Endometriosis

3.2. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in the Population of Women with Endometriosis

3.2.1. 3Q/TMD Questionnaire

3.2.2. TMD Pain Screener Questionnaire

3.2.3. Orthodontic and Orthognathic Treatment and Trauma

3.3. The Relationship Between 3Q/TMD and TMD Pain Screener Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Aspect of the Diagnostic Process of Endometriosis in the General Population

4.2. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Women with Endometriosis

4.3. Links Between Temporomandibular Disorders and Endometriosis

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Online Survey

- Initial data (inclusion criteria)

- Are you of adult age (18+ years old)?

- Yes

- No

- How old are you?

- Do you have a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis by a medical doctor?

- Yes

- No

- Endometriosis—history

- 4.

- When did your first symptoms of endometriosis appear? Provide the date (month and year).

- 5.

- How long after the first symptoms of endometriosis appeared did you go to the doctor? Provide the date (month and year).

- 6.

- How long after your first medical consultation did you receive a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis? Provide the date (month and year).

- 7.

- Have you undergone surgical treatment for endometriosis?

- Yes

- No

- 8.

- When did you have the surgery?

- Temporomandibular disorders—history3Q/TMD Questionnaire

- 1.

- Do you have pain in your temple, face, jaw, or jaw joint once a week or more?

- Yes

- No

- 2.

- Do you have pain once a week or more, when you open your mouth or chew?

- Yes

- No

- 3.

- Does your jaw lock or become stuck once a week or more?

- Yes

- No

- TMD Pain Screener

- In the last 30 days, how long did any pain last in your jaw or temple area on either side?

- No pain

- Pain comes and goes

- Pain is always present

- In the last 30 days, have you had pain or stiffness in your jaw on awakening?

- No

- Yes

- In the last 30 days, did the following activities change any pain (that is, make it better or make it worse) in your jaw or temple area on either side?

- A.

- Chewing hard or tough food

- a.

- No

- b.

- Yes

- B.

- Opening your mouth or moving your jaw forward or to the side

- a.

- No

- b.

- Yes

- C.

- Jaw habits such as holding teeth together, clenching, grinding, or chewing gum

- a.

- No

- b.

- Yes

- D.

- Other jaw activities such as talking, kissing, or yawning

- a.

- No

- b.

- Yes

- Orthodontic treatment, orthognathic treatment, and craniofacial injuries—history

- Have you ever had or are you currently undergoing orthodontic treatment? (braces or overlay treatment)

- I have had orthodontic treatment

- I am undergoing orthodontic treatment

- I have not had orthodontic treatment

- When did you start (or start and finish) orthodontic treatment?

- Did the above-mentioned symptoms of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) appear before, during, or after orthodontic treatment?

- Before treatment

- During treatment

- After treatment

- Not applicable

- Have you had orthognathic treatment (as part of maxillofacial surgery) in the past?

- Yes

- No

- When did you have an orthognathic surgery? Provide the date (month and year).

- Did the above-mentioned symptoms of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) appear before or after orthognathic treatment?

- Before treatment

- After treatment

- Have you ever experienced an injury (e.g., fracture) in the face/head area?

- Yes

- No

- When did the injury occur? Provide the date (month and year).

- Did the above-mentioned symptoms of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) appear before or after the injury?

- Before the injury

- After the injury

References

- Kapos, F.P.; Exposto, F.G.; Oyarzo, J.F.; Durham, J. Temporomandibular Disorders: A Review of Current Concepts in Aetiology, Diagnosis and Management. Oral Surg. 2020, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valesan, L.F.; Da-Cas, C.D.; Réus, J.C.; Denardin, A.C.S.; Garanhani, R.R.; Bonotto, D.; Januzzi, E.; de Souza, B.D.M. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Ginszt, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Global Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Sanders, A.E.; Ohrbach, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Dubner, R.; Gracely, R.H.; Bair, E.; Maixner, W.; Greenspan, J.D. Pressure Pain Thresholds Fluctuate with—But Do Not Usefully Predict—The Clinical Course of Painful Temporomandibular Disorder. Pain 2014, 155, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, S.; Eli, I.; Mahameed, M.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Friedman-Rubin, P.; Reiter, M.; Winocur, E. Pain Catastrophizing and Pain Persistence in Temporomandibular Disorder Patients. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2018, 32, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Goździewicz, T.; Hudáková, Z.; Siatkowski, I. Endometriosis and the Temporomandibular Joint—Preliminary Observations. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, N. The Missed Disease? Endometriosis as an Example of ‘Undone Science’. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online 2021, 14, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałczyński, K.; Jóźwik, M.; Lewkowicz, D.; Semczuk-Sikora, A.; Semczuk, A. Ovarian Endometrioma—A Possible Finding in Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Mini-Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, A.T.; Puckett, Y. Endometrioma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vaduva, C.C.; Dira, L.; Carp-Veliscu, A.; Goganau, A.M.; Ofiteru, A.M.; Siminel, M.A. Ovarian Reserve after Treatment of Ovarian Endometriomas by Ethanolic Sclerotherapy Compared to Surgical Treatment. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 5575–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.; Farland, L.V.; Tobias, D.K.; Gaskins, A.J.; Spiegelman, D.; Chavarro, J.E.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Barbieri, R.L.; Missmer, S.A. A Prospective Cohort Study of Endometriosis and Subsequent Risk of Infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, Y.; Shams-Beyranvand, M.; Khateri, S.; Gharahjeh, S.; Tehrani, S.; Varse, F.; Tiyuri, A.; Najmi, Z. A Systematic Review on the Prevalence of Endometriosis in Women. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggio, L.; Dridi, D.; Barbara, G.; Merli, C.E.M.; Cetera, G.E.; Vercellini, P. Novel Pharmacological Therapies for the Treatment of Endometriosis. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 15, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Viganò, P. Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Wyderka, M.I.; Zalewska, D.; Szeląg, E. Endometrioza a jakość życia. Pielęgniarstwo Pol. 2011, 4, 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Silva de Barros, A.; Mesquita Magalhães, G.; Darc de Menezes Braga, L.; Oliveira Veloso, M.; Olavo de Paula Lima, P.; Moreira da Cunha, R.; Soares Coutinho, S.; Lira do Nascimento, S.; Robson Pinheiro Sobreira Bezerra, L. Musculoskeletal Evaluation of the Lower Pelvic Complex in Women with Endometriosis: A Case-Control Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 299, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulenkul, T.; Kuandyk, A.; Makhadiyeva, D.; Dautova, A.; Terzic, M.; Oshibayeva, A.; Moldaliyev, I.; Ayazbekov, A.; Maimakov, T.; Saruarov, Y.; et al. Understanding the Impact of Endometriosis on Women’s Life: An Integrative Review of Systematic Reviews. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, E.A.; Chen, Y.; Lin, J.-M.S.; Issa, A.; Brimmer, D.J.; Bateman, L.; Lapp, C.W.; Podell, R.N.; Natelson, B.H.; Kogelnik, A.M.; et al. Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions in People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Sample from the Multi-Site Clinical Assessment of ME/CFS (MCAM) Study. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciniak, T.; Kruk-Majtyka, W.; Bobowik, P.; Marszałek, S. The Relationship between Kinesiophobia, Emotional State, Functional State and Chronic Pain in Subjects with/without Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Vale Braido, G.V.; Svensson, P.; dos Santos Proença, J.; Mercante, F.G.; Fernandes, G.; de Godoi Gonçalves, D.A. Are Central Sensitization Symptoms and Psychosocial Alterations Interfering in the Association between Painful TMD, Migraine, and Headache Attributed to TMD? Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenabi, E.; Khazaei, S. Endometriosis and Migraine Headache Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Women Health 2020, 60, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövgren, A.; Visscher, C.M.; Lobbezoo, F.; Yekkalam, N.; Vallin, S.; Wänman, A.; Häggman-Henrikson, B. The Association between Myofascial Orofacial Pain with and without Referral and Widespread Pain. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2022, 80, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Ramos, A.; Álvarez-Salvago, F.; Fernández-Lao, C.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Ocón-Hernández, O.; Mazheika, M.; Salinas-Asensio, M.M.; Mundo-López, A.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; et al. Widespread Pain Hypersensitivity and Lumbopelvic Impairments in Women Diagnosed with Endometriosis. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maixner, W.; Fillingim, R.B.; Williams, D.A.; Smith, S.B.; Slade, G.D. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. J. Pain 2016, 17, T93–T107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, W. Endometriosis and chronic overlapping pain conditions. Schmerz 2021, 35, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Renzulli, F.; Sanna, G.; Raspollini, A.; Bertoldo, L.; Maletta, M.; Lenzi, J.; Rovero, G.; Travaglino, A.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Central Sensitization in Women with Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 73–80.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Touche, R.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Hidalgo-Pérez, A.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; Angulo-Diaz-Parreño, S.; Muñoz-García, D. Evidence for Central Sensitization in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Pain Pract. 2018, 18, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiewicz, M.; Ciapała, B.; Bolt, K.; Kołodziej, P.; Więckiewicz, M.; Ohrbach, R. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD): Polish Assessment Instruments. Dent. Med. Probl. 2024, 61, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lövgren, A.; Visscher, C.M.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Lobbezoo, F.; Marklund, S.; Wänman, A. Validity of Three Screening Questions (3Q/TMD) in Relation to the DC/TMD. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lövgren, A.; Parvaneh, H.; Lobbezoo, F.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Wänman, A.; Visscher, C.M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Three Screening Questions (3Q/TMD) in Relation to the DC/TMD in a Specialized Orofacial Pain Clinic. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, Y.M.; Schiffman, E.; Gordon, S.M.; Seago, B.; Truelove, E.L.; Slade, G.; Ohrbach, R. Development of a Brief and Effective Temporomandibular Disorder Pain Screening Questionnaire. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Soliman, A.M.; Rahal, Y.; Robert, C.; Defoy, I.; Nisbet, P.; Leyland, N. Prevalence, Symptomatic Burden, and Diagnosis of Endometriosis in Canada: Cross-Sectional Survey of 30 000 Women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2020, 42, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, M.; Wielgoś, M.; Laudański, P. Diagnostic Delay of Endometriosis in Adults and Adolescence-Current Stage of Knowledge. Adv. Med. Sci. 2022, 67, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, A.H.J.; van der Zanden, M.; Nap, A.W. Diagnostic Delay of Endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2016, 81, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, V.; Jan, H.; Shakir, F.; Haines, P.; Kent, A. Diagnostic Delay for Superficial and Deep Endometriosis in the United Kingdom. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women with Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, G.K.; Haugen, R.S.; Moen, M.H. Diagnostic Delay in Women with Pain and Endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003, 82, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basta, A.; Brucka, A.; Górski, J.; Kotarski, J.; Kulig, B.; Oszukowski, P.; Poreba, R.; Radowicki, S.; Radwan, J.; Sikora, J.; et al. The statement of Polish Society’s Experts Group concerning diagnostics and methods of endometriosis treatment. Ginekol. Pol. 2012, 83, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. Spectrum of Symptoms in Women Diagnosed with Endometriosis during Adolescence vs Adulthood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 324.e1–324.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis Is a Chronic Systemic Disease: Clinical Challenges and Novel Innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk-Majtyka, W.; Marciniak, T. The relationship between depression, anxiety, chronic pain and pain pressure threshold of the masseter muscle in healthy young subjects. A pilot study. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 16, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 3Q/TMD Positive Answers n = 163 | n | % | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 37 | 22.7 | nTMD |

| 1 | 37 | 22.7 | TMD |

| 2 | 34 | 20.86 | |

| 3 | 55 | 33.74 |

| TMD Pain Screener Points n = 163 | n | % | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 26 | 15.95 | TMD pain negative |

| 1 | 29 | 17.79 | |

| 2 | 28 | 17.18 | |

| 3 | 16 | 9.82 | TMD pain positive |

| 4 | 20 | 12.27 | |

| 5 | 20 | 12.27 | |

| 6 | 17 | 10.43 | |

| 7 | 7 | 4.29 |

| Orthodontic Treatment Status n = 163 | TMD Symptom Appearance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | During | After | nTMD | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| no orthodontic treatment | 93 | 57.06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| during orthodontic treatment | 8 | 4.91 | 5 | 62.5 | 1 | 12.5 | - | - | 2 | 25 |

| orthodontic treatment finished | 62 | 38.03 | 22 | 35.48 | 5 | 8.06 | 23 | 37.1 | 12 | 19.35 |

| Total | 56 TMD subjects (80%) | 14 nTMD subjects (20%) | ||||||||

| TMD-1 | TMD-2 | TMD-3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMD-0 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TMD-1 | - | 0.657 | <0.001 |

| TMD-2 | 0.657 | - | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marciniak, T.; Walewska, N.; Skoworodko, A.; Bobowik, P.; Kruk-Majtyka, W. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Women with Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247615

Marciniak T, Walewska N, Skoworodko A, Bobowik P, Kruk-Majtyka W. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Women with Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(24):7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247615

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarciniak, Tomasz, Natalia Walewska, Agata Skoworodko, Patrycja Bobowik, and Weronika Kruk-Majtyka. 2024. "Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Women with Endometriosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 24: 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247615

APA StyleMarciniak, T., Walewska, N., Skoworodko, A., Bobowik, P., & Kruk-Majtyka, W. (2024). Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Women with Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(24), 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247615