Endometriosis Coinciding with Uterus Didelphys and Renal Agenesis: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Background

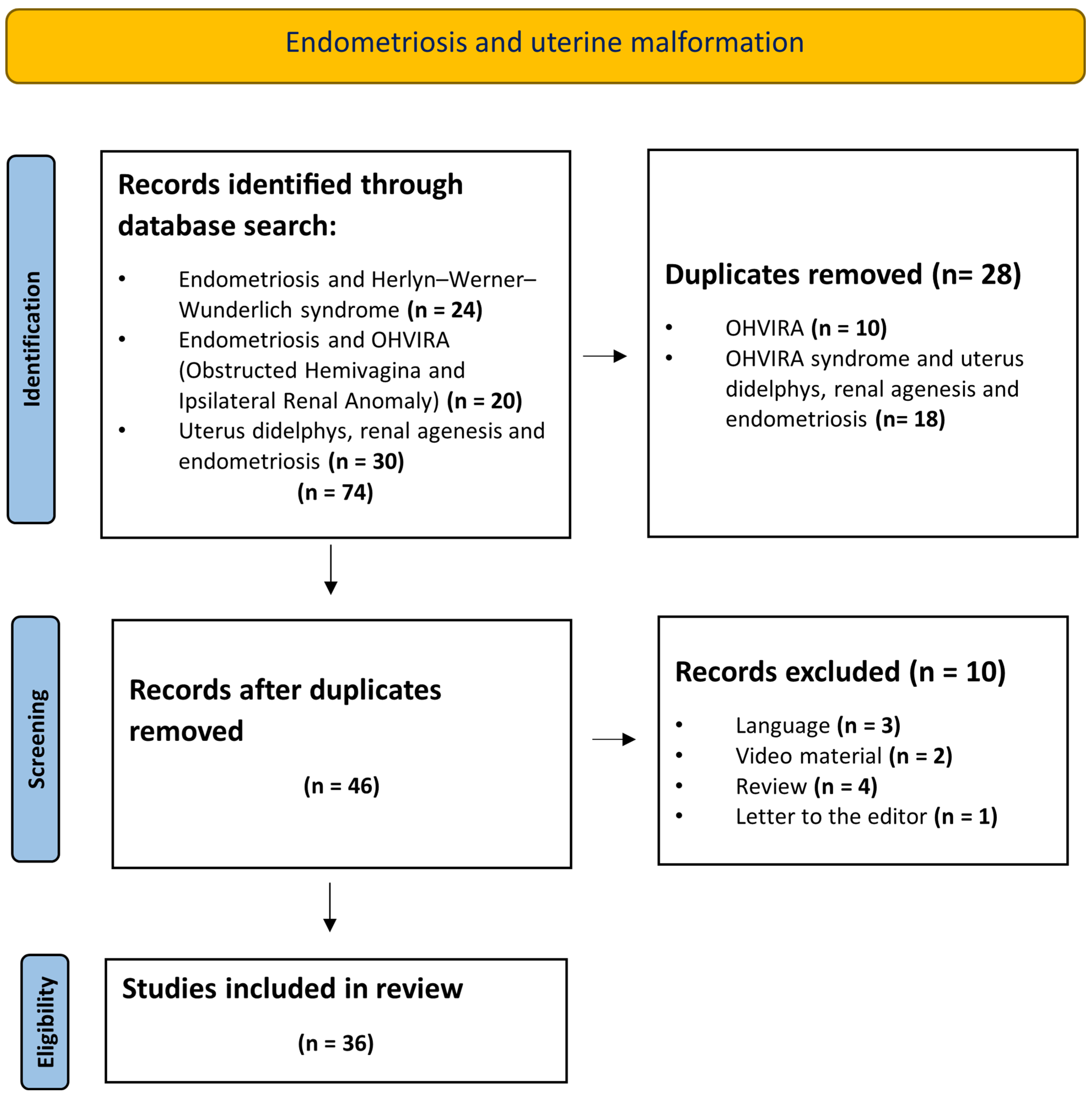

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burghaus, S.; Schafer, S.D.; Beckmann, M.W.; Brandes, I.; Brunahl, C.; Chvatal, R.; Drahonovsky, J.; Dudek, W.; Ebert, A.D.; Fahlbusch, C.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/045, August 2020). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021, 81, 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunselman, G.A.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukac, S.; Schmid, M.; Pfister, K.; Janni, W.; Schaffler, H.; Dayan, D. Extragenital Endometriosis in the Differential Diagnosis of Non- Gynecological Diseases. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2022, 119, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarz, B.; Szyllo, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J.A. Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am. J. Pathol. 1927, 3, 93–110+143. [Google Scholar]

- Boujenah, J.; Salakos, E.; Pinto, M.; Shore, J.; Sifer, C.; Poncelet, C.; Bricou, A. Endometriosis and uterine malformations: Infertility may increase severity of endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, F.; Rahimi, G.; Nawroth, C.; Foth, D.; Ludwig, M.; Schmidt, T. Is there an association between septate uterus and endometriosis? Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, D.L.; Henderson, D.Y. Endometriosis and mullerian anomalies. Obstet. Gynecol. 1987, 69, 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Pitot, M.A.; Bookwalter, C.A.; Dudiak, K.M. Mullerian duct anomalies coincident with endometriosis: A review. Abdom. Radiol. 2020, 45, 1723–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M.; Turan, C.; Mungan, T.; Kuscu, E.; Senoz, S.; Agis, H.T.; Gokmen, O. Endometriosis in association with mullerian anomalies. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1995, 40, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmioglu, N.; Mortlock, S.; Ghiasi, M.; Moller, P.L.; Stefansdottir, L.; Galarneau, G.; Turman, C.; Danning, R.; Law, M.H.; Sapkota, Y.; et al. The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santin, A.; Spedicati, B.; Morgan, A.; Lenarduzzi, S.; Tesolin, P.; Nardone, G.G.; Mazza, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Romano, F.; Buonomo, F.; et al. Puzzling Out the Genetic Architecture of Endometriosis: Whole-Exome Sequencing and Novel Candidate Gene Identification in a Deeply Clinically Characterised Cohort. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.; Chvatal, R.; Reichert, B.; Renner, S.; Shebl, O.; Binder, H.; Wurm, P.; Oppelt, P. Endometriosis: A premenopausal disease? Age pattern in 42,079 patients with endometriosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 286, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, V.H.; Weil, C.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V. Epidemiology of endometriosis: A large population-based database study from a healthcare provider with 2 million members. BJOG 2018, 125, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarfati, A.; Lucchetti, M.C. OHVIRA (Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly or Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome): Is it time for age-specific management? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wen, S.; Liu, X.; He, D.; Wei, G.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hua, Y. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA): Early diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 261, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecka-Ambroziak, A.; Skobejko-Wlodarska, L.; Ruta, H. The Need for Earlier Diagnosis of Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Agenesis/Anomaly (OHVIRA) Syndrome in Case of Renal Agenesis in Girls-Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimbizis, G.F.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Saravelos, S.H.; Gordts, S.; Exacoustos, C.; Van Schoubroeck, D.; Bermejo, C.; Amso, N.N.; Nargund, G.; Timmermann, D.; et al. The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ESGE consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Gynecol. Surg. 2016, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Badawy, S.Z. Unilateral non-communicating cervical atresia in a patient with uterus didelphys and unilateral renal agenesis. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2010, 23, e137–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, A.M.; Peltecu, G.; Gica, N. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, S.M.; Attaran, M.; Goldstein, J.; Lindheim, S.R.; Petrozza, J.C.; Rackow, B.W.; Siegelman, E.; Troiano, R.; Winter, T.; Zuckerman, A.; et al. ASRM mullerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orazi, C.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Schingo, P.M.; Marchetti, P.; Ferro, F. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome: Uterus didelphys, blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. Sonographic and MR findings in 11 cases. Pediatr. Radiol. 2007, 37, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, N.; Lang, J. Endometriosis in association with Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Dou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Anatomical variations, treatment and outcomes of Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome: A literature review of 1673 cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassart, J.P.; Nagel, T.C.; Prem, K.A.; Phipps, W.R. Uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: The University of Minnesota experience. Fertil. Steril. 1992, 57, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choridah, L.; Pangastuti, N. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly syndrome in an association with endometriosis: Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in diagnosis. Med. J. Malays. 2024, 79, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, N.; Harada, M.; Kanatani, M.; Wada-Hiraike, O.; Hirota, Y.; Osuga, Y. The Association between Endometriosis and Obstructive Mullerian Anomalies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goluda, M.; St Gabrys, M.; Ujec, M.; Jedryka, M.; Goluda, C. Bicornuate rudimentary uterine horns with functioning endometrium and complete cervical-vaginal agenesis coexisting with ovarian endometriosis: A case report. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, 462.e9–462.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquinet, A.; Millar, D.; Lehman, A. Etiologies of uterine malformations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 2141–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisma. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Ahmad, Z.; Goyal, A.; Das, C.J.; Deka, D.; Sharma, R. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome presenting with infertility: Role of MRI in diagnosis. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2013, 23, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altchek, A.; Paciuc, J. Successful pregnancy following surgery in the obstructed uterus in a uterus didelphys with unilateral distal vaginal agenesis and ipsilateral renal agenesis: Case report and literature review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2009, 22, e159–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakaki, R.; Yoshida, K.; Imaizumi, J.; Kaji, T.; Kato, T.; Iwasa, T. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis (OHVIRA) syndrome: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 107, 108368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, T.; Pradhan, T.; Yadav, P.; Sah, M.K.; Yadav, J.; Rai, Y.; Thapa, R. Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly Syndrome Rare Obstructive Uterovaginal Anomaly: A Case Report. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2020, 58, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.L.; Sanha, N.; Pereira, H.; Martins, A.; Costa, C. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome also known as obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly: A case report and a comprehensive review of literature. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 2771–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, V.Y. Uterus didelphys with unilateral renal agenesis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2008, 30, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.; Ching, B.H. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome: A rare presentation with pyocolpos. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi Fachin, C.; Aleixes Sampaio Rocha, J.L.; Atuati Maltoni, A.; das Chagas Lima, R.L.; Arias Zendim, V.; Agulham, M.A.; Tsouristakis, A.; Dos Santos Dias, A.I.B. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment of an atypical case and review of literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019, 63, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, A.M.; Yousaf, K.R.; Chaudhary, S.; Amjad, S. The Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich (HWW) syndrome—A case report with radiological review. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaladkar, S.M.; Kamal, V.; Kamal, A.; Kondapavuluri, S.K. The Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome—A Case Report with Radiological Review. Pol. J. Radiol. 2016, 81, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Ruikar, P.D.; Alahabade, R.; Mahajan, R.; Kulkarni, A.V. Vaginoscopic Resection of Oblique Vaginal Septum in OHVIRA Syndrome Before Menarche. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 262–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, Y.; Hirayama, J.; Ota, N.; Ino, K. OHVIRA syndrome pre-operatively diagnosed using vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy: A case report. Med. Int. 2021, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Orisaka, M.; Nishino, C.; Onuma, T.; Kurokawa, T.; Yoshida, Y. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome with cervical atresia complicated by ovarian endometrioma: A case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawfal, A.K.; Blacker, C.M.; Strickler, R.C.; Eisenstein, D. Laparoscopic management of pregnancy in a patient with uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011, 18, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishu, D.S.; Uddin, M.M.; Akter, K.; Akter, S.; Sarmin, M.; Begum, S. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome presenting with dysmenorrhea: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, D.; Mueller, C.; Strubel, N.; Rivera, R.; Ginsburg, H.B.; Nadler, E.P. Laparoscopic neo-os creation in an adolescent with uterus didelphys and obstructed hemivagina. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2006, 41, E19–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Laufer, M.R. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome with a single uterus. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, e39–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Grimstad, F.W.; Laufer, M.R. Spontaneous Cervicovaginal Fistula in Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly Syndrome: A Case Report. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2021, 34, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijmons, A.; Broekhuizen, S.; van der Tuuk, K.; Verhagen, M.; Besouw, M. OHVIRA syndrome: Early recognition prevents genitourinary complications. Ultrasound 2023, 31, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyakusuma, L.S.; Lisnawati, Y.; Pudyastuti, S.; Haloho, A.H. A rare case of pelvic pain caused by Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome in an adult: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 49, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Kawaguchi, R.; Iwai, K.; Waki, K.; Kawahara, N.; Kimura, F. Successful vaginoscopic excision of the vaginal septum in a virgin girl of obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly: Case report and review of literature. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guducu, N.; Gonenc, G.; Isci, H.; Yigiter, A.B.; Dunder, I. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome--timely diagnosis is important to preserve fertility. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2012, 25, e111–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimble, R.M.; Khoo, S.K.; Baartz, D.; Kimble, R.M. The obstructed hemivagina, ipsilateral renal anomaly, uterus didelphys triad. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 49, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, L.M.; Anderson, Z.; Cisneros-Camacho, A.L.; Dietrich, J.E. Presentation and Management of Uterine Didelphys with Unilateral Cervicovaginal Agenesis/Dysgenesis (CVAD): A Multicenter Case Series. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2023, 37, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acien, P.; Acien, M. Unilateral renal agenesis and female genital tract pathologies. Acta. Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapczuk, K.; Friebe, Z.; Iwaniec, K.; Kedzia, W. Obstructive Mullerian Anomalies in Menstruating Adolescent Girls: A Report of 22 Cases. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2018, 31, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapczuk, K.; Zajaczkowska, W.; Madziar, K.; Kedzia, W. Endometriosis in Adolescents with Obstructive Anomalies of the Reproductive Tract. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudela, G.; Wiernik, A.; Drosdzol-Cop, A.; Machnikowska-Sokolowska, M.; Gawlik, A.; Hyla-Klekot, L.; Gruszczynska, K.; Koszutski, T. Multiple variants of obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome—One clinical center case series and the systematic review of 734 cases. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 653.e1–653.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabdia, S.; Sutton, B.; Kimble, R.M. The obstructed hemivagina, ipsilateral renal anomaly, and uterine didelphys triad and the subsequent manifestation of cervical aplasia. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zhu, L.; Lang, J. Clinical characteristics of 70 patients with Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2013, 121, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qu, H.; Ning, G.; Cheng, B.; Jia, F.; Li, X.; Chen, X. MRI in the evaluation of obstructive reproductive tract anomalies in paediatric patients. Clin. Radiol. 2017, 72, 612.e7–612.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yuan, P.; Peng, X.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L. Proposal of the 3O (Obstruction, Ureteric Orifice, and Outcome) Subclassification System Associated with Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly (OHVIRA). J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Y.F.; Smith, Y.R.; Wan, J.; Dendrinos, M.L.; Winfrey, O.K.; Quint, E.H. Should we screen for Mullerian anomalies following diagnosis of a congenital renal anomaly? J. Pediatr. Urol. 2022, 18, 676.e1–676.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.A.; Laufer, M.R. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome: Management and follow-up. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedele, L.; Motta, F.; Frontino, G.; Restelli, E.; Bianchi, S. Double uterus with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: Pelvic anatomic variants in 87 cases. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, T.E.; Siegel, M.J. Mullerian dygenesis, renal agenesis, endometriosis, and ascites. Clin. Pediatr. 2010, 49, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Daguati, R.; Somigliana, E.; Vigano, P.; Lanzani, A.; Fedele, L. Asymmetric lateral distribution of obstructed hemivagina and renal agenesis in women with uterus didelphys: Institutional case series and a systematic literature review. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.N.; Han, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, I.; Han, S.W.; Seo, S.K.; Yun, B.H. Comparison between prepubertal and postpubertal patients with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly syndrome. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 652.e1–652.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.; Quint, E.H. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies: A Review of Surgical Management. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, L.H.; Lindhard, M.S.; Henriksen, T.B.; Forman, A.; Olsen, J.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H. Maternal endometriosis and genital malformations in boys: A Danish register-based study. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.; Matteo, M.; Tinelli, R.; Mitola, P.C.; De Ziegler, D.; Cicinelli, E. Altered uterine contractility in women with chronic endometritis. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca, A.; Beltran, E. Subendometrial contractility in menstrual phase visualized by transvaginal sonography in patients with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1995, 64, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C.; Kao, L.C. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piriyev, E.; Romer, T. Coincidence of uterine malformations and endometriosis: A clinically relevant problem? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholt, D.R.; Low, S.K.; Anderson, C.A.; Painter, J.N.; Uno, S.; Morris, A.P.; MacGregor, S.; Gordon, S.D.; Henders, A.K.; Martin, N.G.; et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Painter, J.N.; Anderson, C.A.; Nyholt, D.R.; Macgregor, S.; Lin, J.; Lee, S.H.; Lambert, A.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Roseman, F.; Guo, Q.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Rahmioglu, N.; Morris, A.P.; Nyholt, D.R.; Montgomery, G.W.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Beyond Endometriosis Genome-Wide Association Study: From Genomics to Phenomics to the Patient. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2016, 34, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Oh, M.J.; Saw, H.S.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, K.W. Septate uterus with double cervices, unilaterally obstructed vaginal septum, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: A rare combination of mullerian and wolffian anomalies complicated by severe endometriosis in an adolescent. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2007, 14, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta Breton, S.; Lopez Carrasco, A.; Hernandez Gutierrez, A.; Rodriguez Gonzalez, R.; de Santiago Garcia, J. Complete loss of unilateral renal function secondary to endometriosis: A report of three cases. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Pulido, J.; Marquez Moreno, A.J.; Julve Villalta, E.; Antuna Calle, F.M.; Ortega Jimenez, M.V.; Sanchez Carrillo, J.J.; Amores Ramirez, F.; Martin Palanca, A. Obstructive uropathy secondary to vesico-ureteral endometriosis: Clinical, radiologic and pathologic features. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2009, 62, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, J.I.; Yoo, J.G.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.N.; Kim, M.J. Acute Renal Failure due to Obstructive Uropathy Secondary to Ureteral Endometriosis. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 2015, 761348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, C.J.; Huang, K.H.; Kung, F.T. Deep infiltrating endometriosis with obstructive uropathy secondary to ureteral endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 160, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country | Patients | Symptoms | Age at Diagnosis in Years | Age at Menarche in Years, Menstrual Cycle | Renal Agenesis Right (R)/Left (L) | Malformation | Treatment | Abdominal Exploration No (N), Yes (Y), Not Available (NA) | Endometriosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies with ≥50 patients | ||||||||||

| Kapczuk K. et al., 2023 [57] | Poland | 50 | 15/50 anomalies associated with cryptomenorrhea, and 35/50 were menstruating | 13.5 (range 11.1–18.5) | 2 girls detected in childhood | 27 (15R/12L) | 27/50 IRA; 22/27 UD, OHV; 1/27 UD with unilateral cervical atresia; 4/27 unicornuate uterus with RUH | 17/50 only VSR (9/17 with IRA); 33/50 AE with LSC or laparotomy (18/33 with IRA) | 33/50 Y | 24/33 endometriosis (15/18 with IRA) |

| Acién P. et al., 2010 [55] | Spain | 60 | pelvic pain/dysmenorrhea, metrorrhagia | 26.6 (range 11–62) | NA | 60 (32R/28L) | 60 IRA; 10 (8R/2L) UD; 8 (5R/3L) bicornis–unicollis uterus; 27 (15R/12L) bicornis–bicollis uterus; 10 (2R/8L) unicornuate uterus | HSG and/or LSC | NA | Bicornuate/didelphys uterus 20% Endometriosis |

| Tong J. et al., 2013 [60] | China | 70 | 45/70 (64.3%) dysmenorrhea; 28/70 (40.0%) intermittent mucopurulent discharge; 18/70 (25.7%) metromenorrhagia | 21.39 (range 10–50) | NA | 70 (42R/28L) | 70 IRA, UD, OHV (20/70 complete obstruction with HC; 50/70 incomplete obstruction) | all patients VSR; 9/70 (12.9%) underwent AE via laparotomy or laparoscopy | 9/70 Y | Endometriosis was observed in 12 (17.1%) patients who underwent AE |

| Tong J. et al., 2014 [23] | China | 94 | NA | endometriosis 17.8 (range 13–32) HWWS 20.5 (range 13–37) | NA | NA | NA | NA | Pelvic endometriosis in 18/94 (19.15%) of patients with HWWS (patients with complete hemivaginal obstruction 10/27 (37.0%) higher than in those with incomplete obstructions 8/67 (11.9%)) | |

| Fei F.Y., 2022 [63] | USA | 125 | abdominal pain and/or dysmenorrhea | 14.5 ± 6.5 (r 0–32) | 12.3 ± 1.6 (r 9–19) | NA | VS 41.6% (52/125), including 39/52 with oblique septum or obstructed hemivagina–ipsilateral renal agenesis (OHVIRA) | 45 VSR | N | NA |

| Case series with ≤28 patients | ||||||||||

| Güdücü N. et al., 2012 [52] | Turkey | 2 | Pat I: dysmenorrhea, Pat. II: foul-smelling vaginal discharge after her menstrual periods | 13, 21 | Pat. I: 12; regular Pat. II: NA | 2 R | Pat. I + II: UD, right OHV with HC, left uterine cavity, cervix and vagina normal | Pat. I: laparotomy, hemi-hysterectomy with salpingectomy. Par. II: VSR | Pat I:Y/Pat. II:N | Pat. I: DIE endometriosis, Pat. II: AE not performed |

| Kimble R. et al., 2009 [53] | Austalia | 4 | dysmenorrhea, abdominal pain | 14 (range 12–17) | 11,7 (range 10–14) | 4 (3R/1L) | 4 IRA, UD, OHV | LSC | Y | 2 endometriosis, 2 no endometriosis |

| Moon L.M. et al., 2023 [54] | USA | 5 | dysmenorrhea (80%), irregular bleeding (40%), acute onset left lower quadrant pain (20%), and abdominal mass (20%) | 16.6 (r 13–27) | 12 (r 11–13) | 5 (1R/4L) | 5 IRA, UD, (3 left uterine horn distended with HM and HS, 3 left cervico-vaginal agenesis, 1 left cervical dysgenesis, 1 right cervical dysgenesis) | 3/5 LSC (2, robotic) uterine horn resection, 1/5 Cervico-vaginal anastomosis + LSC ovarian cystectomy 1/5 cervico-vaginal anastomosis | 4Y, 1N | 3 endometriosis |

| Kudela G. et al., 2021 [58] | Poland | 10 | 9/10 (90%) lower abdominal pain; 1/10 asymptomatic | 13.35 (range 11–15) | mean 12.55 | 10 (7R/3L) | 10 IRA, UD, OHV | 1/10 LSC hemihysterectomy and vaginectomy; 1/10 LSC conversion to laparotomy hemihysterectomy, vaginectomy and salpingectomy; 8/10 only VSR | 2/10 Y | 1 endometriosis, 1 no endometriosis |

| Sabdia S. et al., 2014 [59] | Austalia | 10 | dysmenorrhea | 12 (range 10–14) | NA | 10 (7R/3L) | NA | 8 VSR, 1 vs. excision, 2 patients with cervical aplasia geht laparoscopic hemi-hysterectomy | NA | 6 endometriosis |

| Stassart J.P. et al., 1992 [25] | USA | 15 | dysmenorrhea and increasing pelvic pain | 14.5 (range 6–26) | 11,7 (range 10–15), 1 premenarch | 15 (11R/4L) | 15 IRA, UD, OHV (9/15 complete obstruction with HC; 6/15 incomplete obstruction) | 13/15 underwent AE, 2/15 not AE | 13/15 Y | 7/13 endometriosis |

| Zhang H. et al., 2017 [61] | China | 21 | 16/21 primary amenorrhoea with cyclic pelvic pain; 5/21 progressive dysmenorrhea | 14 (range 10–18) | NA | 6 (4R/2L) | 6/21 IRA; 4/6 UD; 2/6 unicornuate uterus | 1 hymen incision, 4 vaginoplasty; 3 VSR, 11 resection of uterus, 1 resection of RUH, 1 hemihysterectomy | 11/21 Y | 6/11 endometriosis. 3/6 HWWS cases underwent AE and 2/3 were diagnosed with endometriosis |

| Kapczuk K. et al., 2017 [56] | Poland | 22 | dysmenorrhea | 13.1 (range 11.4–18.2) | 12.2 (range 11–15.6) | 22 (13R/9L) | 22 IRA; 18/22 (81.8%) UD + OHV; 1/22 (4.5%) UD + unilateral cervical atresia; 3/22 (13.6%) unicornuate uterus + RUH with functional noncommunicating cavity | 2/22 laparotomy + VSR; 2/22 LSC + VSR; 3/22 laparotomy + RUH removal, 1/22 cervical fenestration + hemihysterectomy; 13/22 only VSR | 8/22 Y | 4/8 pelvic endometiosis stage 1 |

| Zhang J. et al., 2020 [62] | China | 26 | 21/26 (80.8%) dysmenorrhea; 16/26 (61.5%) cystic mass; 11/26 (42.3%) irregular vaginal discharge; 6/26 (23.1%) prolonged menstrual periods | 15.5 (range 10–31) | 11.7 (range 10–15) | 24 NA | 24/26 IRA; 20/26: UD, 2/26 uterus bicornuate, 4/26 uterus septate. 25/26 OHV (17/25 complete obstruction; 8/25 incomplete obstruction) | 25/26 VSR, 1/26 LSC hemi-hysterektomy | NA | NA |

| Zarfati A. et al., 2022 [15] | Italy | 28 | abdominal pain, dysmenorrhea, vaginal discharge, irregular menstruation, infection, palpable abdominal mass, rectal tenesmus | 11.9 (r 0,5–15,7) (7/28 (25%) before menarche, 1/28 (3%) perinatally) | NA | 23 (18R/5L) | 23 IRA, 5 multicystic-dysplastic kidney | 25/28 VSR, 1/28 VSR + LSC ovarian cystectomy (before menarche), 2/28 not yet operated on as not yet in menarche | 1Y (before menarche), 27 N | No endometriosis |

| Case reports with individual cases (n = 1) | ||||||||||

| Ahmad Z. et al., 2013 [31] | India | 1 | primary infertility | 22 | 13; regular | L | IRA, UD, left OHV | laparotomy, cystectomy and adhesiolysis | Y | Endometrioma and peritoneal endometriosis |

| Altchek A. et al., 2009 [32] | USA | 1 | dysmenorrhea and right lower quadrant pain and rectal pressure | 13 | 11; regular | R | IRA, UD, right HC + HM | LSC | Y | Peritoneal endometriosis |

| Arakaki R. et al., 2023 [33] | Japan | 1 | dysmenorrhea and abnormal vaginal discharge | 12 | 11; regular | L | IRA, UD, left OHV | LSC | Y | Endometriosis at the left fallopian tube |

| Basnet T. et al., 2020 [34] | Nepal | 1 | mass associated with pain at vaginal introitus | 17 | 14; irregularly | R | IRA, UD, right HC | VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Borges A.L. et al., 2023 [35] | Portugal | 1 | foul discharge, dysmenorrhea | 17 | 11, regularly | L | IRA, UD, left OHV | VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Cheung V. et al., 2008 [36] | USA | 1 | dysmenorrhea, irregular menstrual cycles | 17 | NA | L | IRA, UD, cyst in the left ovary | LSC cystectomie | Y | Endometioma |

| Cox D. et al., 2012 [37] | USA | 1 | cyclic abdominal pain, enlarged abdominal mass | 17 | 12; regular | L | IRA, UD, left OHV | VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Girardi Fachin C. et al., 2019 [38] | Brazil | 1 | dysmenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever and a palpable abdominal mass in the hypogastric region | 12 | 11; irregular | L | IRA, uterus bicornis (left hemiuterus was distended and connected to the right one only by a myometrial strand) | LSC hemi-hysterectomy | Y | NA |

| Hayat A.M. et al., 2022 [39] | Afghanistan | 1 | dysmenorrhea | 15 | 13; regular | 1R | IRA, UD, right HC + HM, left uterine horn and cervical canal normal | VSR | N | NA |

| Khaladkar S.M. et al., 2016 [40] | India | 1 | dysmenorrhea | 13 | 12; regular | 1L | IRA, UD, left OHV, right uterine cavity, cervix and vagina normal | laparotomy, hemi-hysterectomy | Y | NA |

| Kulkarni A. et al., 2023 [41] | India | 1 | pelvic pain | 12 | premenarchal | 1R | IRA, UD, right HC + HM; left uterine horn and cervical canal normal | vaginoscopic VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Mabuchi Y. et al., 2021 [42] | Japan | 1 | fever and lower abdominal pain | 25 | 11; regular | 1R | IRA, UD, right HC + HM; left uterine horn and cervical canal normal | vaginoscopic VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Miyazaki Y. et al., 2020 [43] | Japan | 1 | dysmenorrhea, cystic mass in the lower pelvic cavity | 20 | 13; regular | 1L | IRA, unicornuate uterus + RUH with functional noncommunicating cavity | LSC left endometrioma and hematosalpinx. | Y | Endometrioma |

| Nawfal K. et al., 2011 [44] | USA | 1 | dysmenorrhea | 20 | 12; irregular | 1R | IRA, UD, OHV, HC | LSC, supracervical hemi-hysterektomy right with in-situ pregnancy | Y | Peritoneal endometriosis |

| Nishu D.S. et al., 2019 [45] | Bangladesh | 1 | dysmenorrhea, right lower abdominal pain | 15 | 15; regular | 1R | IRA, UD, OHV, HC | vaginoplasty VSR | N | AE not performed |

| Patterson D. et al., 2006 [46] | USA | 1 | progressive cyclic rectal pain, chronic constipation | 10 | NA | 1R | IRA, UD, OHV, HC+ HM | LSC and vaginoscopy | Y | No endometriosis |

| Shah D.K. et al., 2011 [47] | USA | 1 | dysmenorrhea and metrorrhagia | 12 | NA | 1R | IRA, UD, OHV, HM | VSR, 2 years later LSK | Y | Endometriosis stage 1 |

| Shim J. et al., 2020 [48] | USA | 1 | dysmenorrhea and increasing pelvic pain | 15 | 14 | 1R | IRA, UD, HM, OHV with communication between the right hemivagina and the left cervix | robot-assisted hemihysterectomy and fallopian tube | Y | NA |

| Sijmons A. et al., 2023 [49] | Netherlands | 1 | anuria and intralabial mass | 1 day | 1R | multicystic dysplastic kidney, UD, OHV and an ectopic ureteric insertion. | hymen incision, nephrectomy | NA | NA | |

| Widyakusuma L.S. et al., 2018 [50] | Indonesia | 1 | acute pelvic pain, dysmenorrea, cystic mass with a smooth surface in the right lateral region of the midline | 23 | 12; regular | 1R | 1 IRA, UD, OHV | VSR | N | NA |

| Yamada Y. et al., 2023 [51] | Japan | 1 | dysmenorrhea and lower abdominal pain | 12 | 12 | 1R | 1 IRA, UD, OHV | vaginoscopic VSR | N | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dayan, D.; Ebner, F.; Janni, W.; Hancke, K.; Adiyaman, D.; Huener, B.; Hensel, M.; Hartkopf, A.D.; Schmid, M.; Lukac, S. Endometriosis Coinciding with Uterus Didelphys and Renal Agenesis: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247530

Dayan D, Ebner F, Janni W, Hancke K, Adiyaman D, Huener B, Hensel M, Hartkopf AD, Schmid M, Lukac S. Endometriosis Coinciding with Uterus Didelphys and Renal Agenesis: A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(24):7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247530

Chicago/Turabian StyleDayan, Davut, Florian Ebner, Wolfgang Janni, Katharina Hancke, Duygu Adiyaman, Beate Huener, Michelle Hensel, Andreas Daniel Hartkopf, Marinus Schmid, and Stefan Lukac. 2024. "Endometriosis Coinciding with Uterus Didelphys and Renal Agenesis: A Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 24: 7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247530

APA StyleDayan, D., Ebner, F., Janni, W., Hancke, K., Adiyaman, D., Huener, B., Hensel, M., Hartkopf, A. D., Schmid, M., & Lukac, S. (2024). Endometriosis Coinciding with Uterus Didelphys and Renal Agenesis: A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(24), 7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247530