A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far?

Abstract

1. Introduction

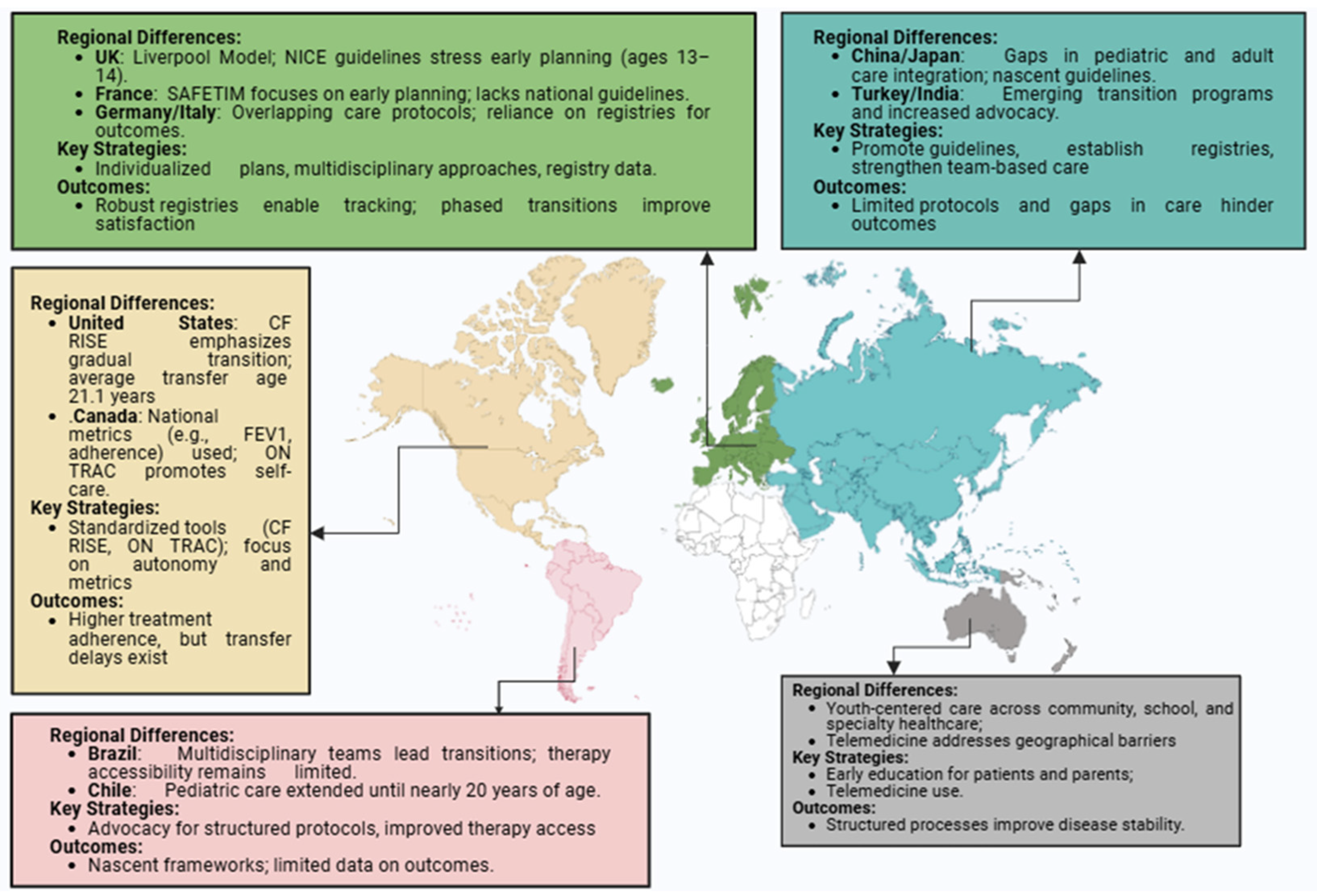

2. Components of a Successful Transition in CF Care

3. Regional Approaches to Transition

3.1. North America (US and Canada)

3.2. Europe

3.3. Australia and New Zealand

3.4. Asia

3.5. Latin America

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liberski, S.; Confalonieri, F.; Cofta, S.; Petrovski, G.; Kocięcki, J. Ocular Changes in Cystic Fibrosis: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Bicker, J.; Alves, G.; Falcão, A.; Fortuna, A. Cystic fibrosis: Physiopathology and the latest pharmacological treatments. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 162, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.; Ramsey, B.W. Cystic fibrosis: A review. JAMA 2023, 329, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBennett, K.A.; Davis, P.B.; Konstan, M.W. Increasing life expectancy in cystic fibrosis: Advances and challenges. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57 (Suppl. S1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, M.J. The arc of discovery, from the description of cystic fibrosis to effective treatments. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e186231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvé, P.; Saint Pierre, A.; Férec, C. Cystic Fibrosis: A Journey through Time and Hope. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Registry. Annual Data Report 2018. Available online: https://www.cysticfibrosis.ca/uploads/RegistryReport2018/2018RegistryAnnualDataReport.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Chalmers, J.D. Cystic fibrosis lung disease and bronchiectasis. Lancet Resp. Med. 2020, 8, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.C.; Machuca, T.N.; Chaparro, C.; Cypel, M.; Stephenson, A.L.; Solomon, M.; Saito, T.; Binnie, M.; Chow, C.-W.; Grasemann, H.; et al. Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2020, 39, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Towns, S.; Jayasuriya, G.; Hunt, S.; Simonds, S.; Boyton, C.; Middleton, A.; Kench, A.; Pandit, C.; Keatley, L.R.; et al. Transition to adult care in cystic fibrosis: The challenges and the structure. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2020, 41, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Baliss, M.; Saikumar, P.; Numan, L.; Teckman, J.; Hachem, C. A Gastroenterologist’s Guide to Care Transitions in Cystic Fibrosis from Pediatrics to Adult Care. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, K.; George, M.; Sadeghi, H.; Piane, V.; Smaldone, A. Moving up: Healthcare transition experiences of adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 65, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.C.; Mall, M.A.; Gutierrez, H.; Macek, M.; Madge, S.; Davies, J.C.; Burgel, P.R.; Tullis, E.; Castanos, C.; Castellani, C.; et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: A global perspective. Lancet Resp. Med. 2020, 8, 65–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.N.; Schaefer, M.R.; Resmini-Rawlinson, A.; Wagoner, S.T. Barriers to transition from pediatric to adult care: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, S.; Otten, J.; Blusi, M.; Lundberg, E.; Hörnsten, Å. Experiences of transition to adulthood and transfer to adult care in young adults with type 1 diabetes: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 4621–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butalia, S.; McGuire, K.A.; Dyjur, D.; Mercer, J.; Pacaud, D. Youth with diabetes and their parents’ perspectives on transition care from pediatric to adult diabetes care services: A qualitative study. Health Sci. Rep. 2020, 3, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; Farrant, B.; Byrnes, C.A. Transitioning from paediatric to adult services with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis: What is the impact on engagement and health outcomes? J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2021, 57, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middour-Oxler, B.; Bergman, S.; Blair, S.; Pendley, S.; Stecenko, A.; Hunt, W.R. Formal vs. informal transition in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A retrospective comparison of outcomes. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 62, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, L.; Hudson, J.; Potter, E.; Raymond, K.F.; George, C.; Georgiopoulos, A.M. Clinical communication preferences in cystic fibrosis and strategies to optimize care. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darukhanavala, A. Automatic referrals within a cystic fibrosis multidisciplinary clinic improves patient evaluation and management. In Pediatric Pulmonology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 55, p. S88. [Google Scholar]

- Lusman, S.S.; Borowitz, D.; Marshall, B.C.; Narkewicz, M.R.; Gonska, T.; Grand, R.J.; Simon, R.H.; Mascarenhas, M.R.; Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Freedman, S.D. DIGEST: Developing innovative gastroenterology specialty training. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.F.; Close, C.T.; Mailes, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.J.; Goetz, D.M.; Filigno, S.S.; Preslar, R.; Tran, Q.T.; Hempstead, S.E.; Lomas, P.; et al. Cystic fibrosis foundation position paper: Redefining the cystic fibrosis care team. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 24, S1569–S1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.; Duff, A.J.; Bell, S.C.; Heijerman, H.G.; Munck, A.; Ratjen, F.; Sermet-Gaudelus, I.; Southern, K.W.; Barben, J.; Flume, P.A.; et al. ECFS best practice guidelines: The 2018 revision. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, K. Cystic fibrosis in the year 2020: A disease with a new face. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgel, P.R.; Southern, K.W.; Addy, C.; Battezzati, A.; Berry, C.; Bouchara, J.P.; Brokaar, E.; Brown, W.; Azevedo, P.; Durieu, I.; et al. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF); recognising and addressing CF health issues. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 23, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulany, A.; Willem Gorter, J.; Harrison, M. A call for action: Recommendations to improve transition to adult care for youth with complex health care needs. Paediatr. Child. Health 2022, 27, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office, D.; Madge, S. Transition in cystic fibrosis: An international experience. In Transition from Pediatric to Adult Healthcare Services for Adolescents and Young Adults with Long-term Conditions: An International Perspective on Nurses’ Roles and Interventions; Betz, C.L., Coyne, I.T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gramegna, A.; Addy, C.; Allen, L.; Bakkeheim, E.; Brown, C.; Daniels, T.; Davies, G.; Davies, J.C.; De Marie, K.; Downey, D.; et al. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF); Planning for a longer life. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 23, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.; Barto, T.L. Cystic Fibrosis: A Successful Model of Transition of Care and Lessons Learned. Sleep Med. 2023, 1, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Sheehan, A.M.; Heery, E.; While, A.E. Improving transition to adult healthcare for young people with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. J. Child. Health Care 2017, 21, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cystic Fibrosis Trust. UK Cystic Fibrosis Registry Annual Data Report 2019: At a Glance. Available online: www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-12/2019%20Registry%20Annual%20Data%20report%20%20at%20a%20glance.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Sawicki, G.S.; Ostrenga, J.; Petren, K.; Fink, A.K.; D’Agostino, E.; Strassle, C.; Schechter, M.S.; Rosenfeld, M. Risk factors for gaps in care during transfer from pediatric to adult cystic fibrosis programs in the United States. Ann. Am. Thoracic Soc. 2018, 15, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankaskas, J.R.; Marshall, B.C.; Sufian, B.; Simon, R.H.; Rodman, D. Cystic fibrosis adult care: Consensus conference report. Chest 2004, 125, 1S–39S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapnadak, S.G.; Dimango, E.; Hadjiliadis, D.; Hempstead, S.E.; Tallarico, E.; Pilewski, J.M.; Faro, A.; Albright, J.; Benden, C.; Blair, S.; et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus guidelines for the care of individuals with advanced cystic fibrosis lung disease. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020, 19, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Singh, D.A. Essentials of the US Health Care System; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella, K.; Epstein, R.M. The profound implications of the meaning of health for health care and health equity. Milbank Q. 2023, 101, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salsberg, E.; Richwine, C.; Westergaard, S.; Martinez, M.P.; Oyeyemi, T.; Vichare, A.; Chen, C.P. Estimation and comparison of current and future racial/ethnic representation in the US health care workforce. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e213789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auth, R.; Catanese, S.; Banerjee, D. Integrating primary care into the management of cystic fibrosis. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231173811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcı, M.S.; Gökdemir, Y.; Eralp, E.E.; Ergenekon, A.P.; Yegit, C.Y.; Yanaz, M.; Gulieva, A.; Kalyoncu, M.; Karabulut, S.; Cakar, N.M.; et al. Assessment of patients’ baseline cystic fibrosis knowledge levels following translation and adaptation of the CF RISE translation program into Turkish. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 3483–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melton, K.; Liu, J.; Sadeghi, H.; George, M.; Smaldone, A. Predictors of Transition Outcomes in Cystic Fibrosis: Analysis of National Patient Registry and CF RISE (Responsibility. Independence. Self-care. Education) Data. J. Pediatr. 2024, 265, 113812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsner, M.; Sutharsan, S.; Taube, C.; Olivier, M.; Mellies, U.; Stehling, F. Changes in clinical markers during a short-term transfer program of adult cystic fibrosis patients from pediatric to adult care. Open Respir. Med. J. 2019, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Soper, A.K.; McCauley, D.; Gorter, J.W.; Doucet, S.; Greenaway, J.; Luke, A. Landscape of healthcare transition services in Canada: A multi-method environmental scan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravelle, A.M. Bridging pediatric and adult healthcare settings in a nurse-led cystic fibrosis transition initiative. In Transition from Pediatric to Adult Healthcare Services for Adolescents and Young Adults with Long-Term Conditions: An International Perspective on Nurses’ Roles and Interventions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravelle, A.M.; Paone, M.; Davidson, A.G.F.; Chilvers, M.A. Evaluation of a multidimensional cystic fibrosis transition program: A quality improvement initiative. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, K.; Lee, S.; de Los Reyes, T.; Lo, L.; Cleverley, K.; Pidduck, J.; Mahood, Q.; Gorter, J.W.; Toulany, A. Quality indicators for youth transitioning to adult care: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2021055033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, K.; Avolio, J.; Lo, L.; Gajaria, A.; Mooney, S.; Greer, K.; Martens, H.; Tami, P.; Pidduck, J.; Cunningham, J.; et al. Social and structural drivers of health and transition to adult care. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023062275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M.; Visonà Dalla Pozza, L.; Minichiello, C.; Manea, S.; Barbieri, S.; Toto, E.; Vianello, A.; Facchin, P. The Epidemiology of Transition into Adulthood of Rare Diseases Patients: Results from a Population-Based Registry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the Application of Patients’ Rights in Cross-Border Healthcare. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:088:0045:0065:en:PDF (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Pohunek, P.; Manali, E.; Vijverberg, S.; Carlens, J.; Chua, F.; Epaud, R.; Gilbert, C.; Griese, M.; Karadag, B.; Kerem, E.; et al. ERS statement on transition of care in childhood interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2302160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, V.V.; Perceval, M.; Buscarlet-Jardine, L.; Pinsault, N.; Gauchet, A.; Allenet, B.; Llerena, C. Smoothing the transition of adolescents with CF from pediatric to adult care: Pre-transfer needs. Arch. Pédiatr. 2021, 28, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeres, I. Transition from paediatric to adult care in cystic fibrosis. Breathe 2022, 18, 210157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, S.; Bell, S.C.; Burgel, P.R.; De Rijcke, K.; Blasi, F.; Elborn, J.S. Limitations to providing adult cystic fibrosis care in Europe: Results of a care centre survey. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.H.; Tanner, K.; Simmonds, N.J.; Bilton, D. The changing demography of the cystic fibrosis population: Forecasting future numbers of adults in the UK. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Robinson, D.; Archangelidi, O.; Carr, S.B.; Cosgriff, R.; Gunn, E.; Keogh, R.H.; MacDougall, A.; Newsome, S.; Schluter, D.K.; Stanojevic, S.; et al. Data Resource Profile: The UK Cystic Fibrosis Registry. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 9–10e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, J.A.; Lewis, P.A.; Stanton, M.; Wilsher, J. Cystic fibrosis mortality and survival in the UK: 1947–2003. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.R.; McDonagh, J.E. Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services (NICE Guideline NG43). Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2018, 103, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, D.; Walshaw, M. Coming of age in cystic fibrosis–transition from paediatric to adult care. Clin. Med. 2013, 13, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrézet, M.P.; Munck, A. Newborn screening for CF in France: An exemplary national experience. Arch. Pédiatr. 2020, 27, eS35–eS40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munck, A.; Cheillan, D.; Audrezet, M.P.; Guenet, D.; Huet, F. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis in France. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regard, L.; Martin, C.; Burnet, E.; Da Silva, J.; Burgel, P.-R. CFTR Modulators in People with Cystic Fibrosis: Real-World Evidence in France. Cells 2022, 11, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, G.; Magne, F.; Nove Josserand, R.; Durupt, S.; Durieu, I.; Reix, P.; Reynaud, Q. A formalized transition program for cystic fibrosis: A 10-year retrospective analysis of 97 patients in Lyon. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2000–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, V.V.; Perceval, M.; Jardine, L.B.; Pinsault, N.; Gauchet, A.; Allenet, B.; Llerena, C. P041 What are patients’ and parents’ expectations during transition process in the French cystic fibrosis centres (SAFETIM Needs study). J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020, 19, S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vion-Génovèse, V.; Gauchet, A.; Perceval, M.; Buscarle-Jardine, L.; Pinsault, N.; Llerena, C.; Durieux, L. Critères de qualité pour la transition dans la mucoviscidose en France. Rev. Des Mal. Respir. 2019, 36, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, G.; Dalmastri, C.; Tabacchioni, S.; Vandamme, P.; Lorini, R.; Minicucci, L.; Romano, L.; Giannattasio, A.; Chiarini, L.; Bevivino, A. Epidemiology and clinical course of Burkholderia cepacia complex infections, particularly those caused by different Burkholderia cenocepacia strains, among patients attending an Italian cystic fibrosis center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, D.; Padoan, R.; Amato, A.; Salvatore, M.; Campagna, G.; Italian Cf Registry Working Group. Nutritional Trends in Cystic Fibrosis: Insights from the Italian Cystic Fibrosis Patient Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elli, L.; Maieron, R.; Martelossi, S.; Guariso, G.; Buscarini, E.; Conte, D.; di Giulio, E.; Staiano, A.; Barp, J.; Bassotti, G.; et al. Transition of gastroenterological patients from paediatric to adult care: A position statement by the Italian Societies of Gastroenterology. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, B.; Steinkamp, G.; Sens, B.; Stern, M. The German cystic fibrosis quality assurance project: Clinical features in children and adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 17, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.; Wiedemann, B.; Wenzlaff, P. From registry to quality management: The German Cystic Fibrosis Quality Assessment project 1995–2006. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez Fernandez, A.; Blasi, F.; Gramegna, A.; Elborn, S.; Felipe Montiel, A.; Culebras Amigo, M.; Polverino, E. Standards of care and educational gaps in adult cystic fibrosis units: A European Respiratory Society survey. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00065–02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towns, S.J.; Bell, S.C. Transition of adolescents with cystic fibrosis from paediatric to adult care. Clin. Respir. J. 2011, 5, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.; Sattoe, J.; van Staa, A.; Versteeg, S.E.; Heeres, I.; Rutjes, N.W.; Janssens, H.M. Controlled evaluation of a transition clinic for Dutch young people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staa, A.; Peeters, M.; Sattoe, J. On your own feet: A practical framework for improving transitional care and young people’s self-management. In Transition from Pediatric to Adult Healthcare Services for Adolescents and Young Adults with Long-Term Conditions: An International Perspective on Nurses’ Roles and Interventions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 191–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.L.; Bilton, D. The impact of national cystic fibrosis registries: A review series. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elborn, J.S.; Gonska, T. Using registries for research in CF. How can we be sure about the outputs? J. Cyst. Fibros. 2019, 18, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, A.; Jarvis, D.; Keogh, R.H.; Bowerman, C.; Bilton, D.; Davies, G.; Carr, S.B.; Stanojevic, S. Trajectories of early growth and subsequent lung function in cystic fibrosis: An observational study using UK and Canadian registry data. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnovšek, A.; Praprotnik, M.; Krivec, U.; Aldeco, M.; Lepej, D.; Šmid, S.Š.; Zver, A.; Oštir, M.; Seme, K.; Brecelj, J.; et al. Review and assessment of disease indicators in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis in Slovenia. Slov. Med. J. 2023, 92, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahting, S.; Nährlich, L.; Held, I.; Henn, C.; Krill, A.; Landwehr, K.; Meister, J.; Nahrig, S.; Nolde, A.; Remke, K.; et al. Every CFTR variant counts–Target-capture based next-generation-sequencing for molecular diagnosis in the German CF Registry. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 23, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, D.K.; Southern, K.W.; Dryden, C.; Diggle, P.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Impact of newborn screening on outcomes and social inequalities in cystic fibrosis: A UK CF registry-based study. Thorax 2020, 75, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKone, E.F.; Ariti, C.; Jackson, A.; Zolin, A.; Carr, S.B.; Orenti, A.; van Rens, J.G.; Lemonnier, L.; Macek, M., Jr.; Keogh, R.H.; et al. Survival estimates in European cystic fibrosis patients and the impact of socioeconomic factors: A retrospective registry cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2002288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerem, E.; Orenti, A.; Adamoli, A.; Hatziagorou, E.; Naehrlich, L.; Sermet-Gaudelus, I. Cystic fibrosis in Europe: Improved lung function and longevity–reasons for cautious optimism, but challenges remain. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2301241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osan, S.N.; Hrapsa, I.; Coroama, C.I.; Miclea, D.L.; Al-Khzouz, C.; Lazar, C.; Farcas, M.F. Prevalence of∆ F508 cystic fibrosis carriers in a Romanian population group. Rev. Romana Med. Lab. 2021, 29, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolin, A.; Bossi, A.; Cirilli, N.; Kashirskaya, N.; Padoan, R. Cystic fibrosis mortality in childhood. Data from European Cystic Fibrosis Society patient registry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, C.M.; Cohen, E.; Bhawra, J.; Weiser, N.; Hayeems, R.Z.; Guttmann, A. Health system strategies supporting transition to adult care. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Chan, P.; Christensen, B.; Havrlant, R.; Giles, E.; Williams, A.J. Pediatric to Adult Transition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Consensus Guidelines for Australia and New Zealand. Inflamm. Bow Dis. 2024, 20, izae087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthikumar, S.; Ruseckaite, R.; Corda, J.; Mulrennan, S.; Ranganathan, S.; Douglas, T. Telehealth use in Australian cystic fibrosis centers: Clinician experiences. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 2906–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumit, M.; Chuang, S.; Middleton, P.; Selvadurai, H.; Sivam, S.; Ruseckaite, R.; Ahern, H.; Mallitt, K.A.; Pacey, V.; Gray, K.; et al. Clinical outcomes of adults and children with cystic fibrosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.A.; Mulrennan, S.; Fitzgerald, D.A.; Prentice, B.; Frayman, K.; Messer, M.; Bearcroft, A.; Boyd, C.; Middleton, P.; Wark, P. Standards of Care for Cystic Fibrosis; Cystic Fibrosis Australia: North Ryde, Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.; Singh, B.; Payne, D.N.; Bharat, C.; Noffsinger, W.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; O’Dea, C.; Mulrennan, S. Effect of transfer from a pediatric to adult cystic fibrosis center on clinical status and hospital attendance. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hng, S.Y.; Thinakaran, A.S.; Ooi, C.J.; Eg, K.P.; Thong, M.K.; Tae, S.K.; Goh, S.H.; Chew, K.S.; Tan, T.L.; Koh, M.T.; et al. Morbidity and treatment costs of cystic fibrosis in a middle-income country. Singap. Med. J. 2023, 20, 10-4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Cheok, G.; Goh, A.E.; Han, A.; Hong, S.J.; Indawati, W.; Lutful Kabir, A.R.M.; Kabra, S.K.; Kamalaporn, H.; Kim, H.Y.; et al. Cystic fibrosis in Asia. Pediatr. Respirol. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; King, I.; Hill, A. International disparities in diagnosis and treatment access for cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobbo, K.A.; Ahmad, U.; Chau, D.M.; Nordin, N.; Abdullah, S. A comprehensive review of cystic fibrosis in Africa and Asia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Alliance for Rare Diseases, B.C.; Chinese Experts Cystic Fibrosis Consensus Committee. Chinese experts consensus statement: Diagnosis and treatment of cystic fibrosis. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi = Chin. J. Tuberculos Respir. Dis. 2023, 46, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Factors influencing the healthcare transition in Chinese adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A multi-perspective qualitative study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; de Ferris, M.D.G.; Qin, J. Translation and validation of the STARx questionnaire in transitioning Chinese adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 71, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawase, M.; Ogawa, M.; Hoshina, T.; Kojiro, M.; Nakakuki, M.; Naruse, S.; Ishiguro, H.; Kusuhara, K. Case Report: Japanese Siblings of Cystic Fibrosis with a Novel Large Heterozygous Deletion in the CFTR Gene. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 9, 800095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takei, S.; Shiramizu, M.; Sato, Y.; Kato, T. Carry-over patients of childhood chronic diseases. J. Child. Health 2007, 66, 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, I.; Maru, M.; Miyamae, T.; Honda, M. Prevalence and barriers to health care transition for adolescent patients with childhood-onset chronic diseases across Japan: A nation-wide cross-sectional survey. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 956227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, Y.; Higashino, H.; Kaneko, K. Promotion of the transition of adult patients with childhood-onset chronic diseases among pediatricians in Japan. Front. Pediatr. 2016, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaki-Nakamura, M.; Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, A.; Kita, S.; Sato, I.; Iwasaki, M.; Hirata, Y.; Sato, A.; Oka, A.; Kamibeppu, K. Efficacy of a transitional support program among adolescent patients with childhood-onset chronic diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 829602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Transition Support Independence Support Information-Sharing Website for Patients with Childhood-Onset Chronic Illnesses. Health Care Transition Core Guide. Available online: https://transition-support.jp/ikou/guide (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Motoki, H.; Yasukochi, S.; Takigiku, K.; Takei, K.; Okamura, T.; Kimura, K.; Minamisawa, M.; Okada, A.; Saigusa, T.; Ebisawa, S.; et al. Establishment of a health care system for patients with adult congenital heart disease in collaboration with children’s hospital-the nagano model. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çobanoğlu, N.; Özçelik, U.; Çakır, E.; Eyüboğlu, T.S.; Pekcan, S.; Cinel, G.; Yalçın, E.; Kiper, N.; Emiralioğlu, N.; Şen, V.; et al. Patients eligible for modulator drugs: Data from cystic fibrosis registry of Turkey. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokdemir, Y.; Selçuk, M.; Eralp, E.E.; Ergenekon, A.; Yegit, C.Y.; Yanaz, M.C.; Guliyeva, A.; Kalyoncu, M.; Karabulut, S.; Cakar, N.M.; et al. Cystic fibrosis transition program (CF RISE) translated to Turkish (KF SOBE): First annual results. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, S345–S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torun, T.; Çavuşoğlu, H.; Doğru, D.; Özçelik, U.; Tural, D.A. The effect of self-efficacy, social support and quality of life on readiness for transition to adult care among adolescents with cystic fibrosis in Turkey. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 57, e79–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, D.; Çakır, E.; Şişmanlar, T.; Çobanoğlu, N.; Pekcan, S.; Cinel, G.; Yalçın, E.; Kiper, N.; Sen, V.; Sen, H.S.; et al. Cystic fibrosis in Turkey: First data from the national registry. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogru, D.; Çakır, E.; Eyüboğlu, T.Ş.; Pekcan, S.; Özçelik, U. Cystic fibrosis in Turkey. Lancet Respirator. Med. 2020, 8, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhochak, N.; Kabra, S.K. Transition care in cystic fibrosis. Indian J. Pediatr. 2023, 90, 1223–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Joshi, S.M. Transition of Care-The Time is Now! Indian J. Pediatr. 2023, 90, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Sahay, S. Healthcare needs and programmatic gaps in transition from pediatric to adult care of vertically transmitted HIV infected adolescents in India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S. Health care transition: Need of the hour. Indian. J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, J.; Peter, A.M.; Nayar, L.; Kannankulangara, A. Need and feasibility of a transition clinic for adolescents with chronic illness: A qualitative study. Indian. J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, J.; Manglani, M.; Aneja, S.; Vinayan, K.P.; Sinha, A.; Mandal, P.; Mishra, D.; Seth, R.; Kinjawadekar, U. The Indian Academy of Pediatrics and Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India White Paper on Transition of Care for Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Indian. Pediatr. 2024, 61, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Valdez, J.A.; Aguilar-Alonso, L.A.; Gándara-Quezada, V.; Ruiz-Rico, G.E.; Ávila-Soledad, J.M.; Reyes, A.A.; Pedroza-Jiménez, F.D. Cystic fibrosis: Current concepts. Bol. Méd. Hosp. Infant. Méx. 2021, 78, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, L.V.R.F.; Castaños, C.; Ruíz, H.H. Cystic fibrosis in Latin America—Improving the awareness. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2016, 15, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Garratt, A.; Hill, A. Worldwide rates of diagnosis and effective treatment for cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022, 21, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotet, V.; Gutierrez, H.; Farrell, P.M. Newborn screening for CF across the globe—Where is it worthwhile? Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.V.R.F.; Zampoli, M.; Cohen-Cymberknoh, M.; Kabra, S.K. Cystic fibrosis in low and middle-income countries (LMIC): A view from four different regions of the world. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2021, 38, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, M.E.; Gibb, E.R.; Oates, G.R.; Schechter, M.S. Left behind: The potential impact of CFTR modulators on racial and ethnic disparities in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr. Respir. Rew. 2022, 42, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procianoy, E.D.F.A.; Ludwig Neto, N.; Ribeiro, A.F. Patient care in cystic fibrosis centers: A real-world analysis in Brazil. J. Brasil. Pneumol. 2023, 49, e20220306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarew, T.; Correa, L.; Bedregal, P.; Besoain, C.; Reinoso, A.; Velarde, M.; Venezuela, M.T.; Inostroza, C. Transition from pediatric to adult health care services for adolescents with chronic diseases: Recommendations from the Adolescent Branch from Sociedad Chilena de Pediatría. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2017, 88, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainstock, D.; Katz, A. Advancing rare disease policy in Latin America: A call to action. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 2023, 18, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmerski, T.M.; Stransky, O.M.; Lavage, D.R.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Sawicki, G.S.; Ladores, S.L.; Godfrey, E.M.; Aitken, M.L.; Fields, A.; Sufian, S.; et al. Sexual and reproductive health experiences and care of adult women with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemayor, K.; Tullis, E.; Jain, R.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L. Management of pregnancy in cystic fibrosis. Breathe 2022, 18, 220005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Kazmerski, T.M.; Zuckerwise, L.C.; West, N.E.; Montemayor, K.; Aitken, M.L.; Cheng, E.; Roe, A.H.; Wilson, A.; Mann, C.; et al. Pregnancy in cystic fibrosis: Review of the literature and expert recommendations. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022, 21, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, M.; Pollak, M.; Bar-Yoseph, R.; Bentur, L. Pregnancy in cystic fibrosis—Past, present, and future. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan, B.; Suner, Z.U.; Kocakaya, D.; Yıldızeli, Ş.O.; Eryüksel, E. Impact of Anxiety, Depression, and Coping Strategies on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Thorac. Res. Pract. 2024, 25, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittner, A.L.; Abbott, J.; Hussain, S.; Ong, T.; Uluer, A.; Hempstead, S.; Lomas, P.; Smith, B. Integration of mental health screening and treatment into cystic fibrosis clinics: Evaluation of initial implementation in 84 programs across the United States. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2995–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, G.; Tagliati, C.; Giuseppetti, G.M.; Ripani, P. Treatment of Psychological Symptoms in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Smith, B.A.; Bruce, A.; Schwartz, C.E.; Lee, H.; Pinsky, H.; Gootkind, E.; Hardcastle, M.; Shea, N.; Roach, C.M. Feasibility and acceptability of a CF-specific cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for adults integrated into team-based care. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobra, R.; Carroll, S.; Davies, J.C.; Dowdall, F.; Duff, A.; Elderton, A.; Georgiopoulos, A.M.; Massey-Chase, R.; McNally, P.; Puckey, M.; et al. Exploring the complexity of cystic fibrosis (CF) and psychosocial wellbeing in the 2020s: Current and future challenges. Paediatr Respir. Rev. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladores, S.; Polen, M. Lingering identity as chronically ill and the unanticipated effects of life-changing precision medicine in cystic fibrosis: A case report. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 2374373521996971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girón, R.M.; Peláez, A.; Ibáñez, A.; Martínez-Besteiro, E.; Gómez-Punter, R.M.; Martínez-Vergara, A.; Ancochea, J.; Morell, A. Longitudinal study of therapeutic adherence in a cystic fibrosis unit: Identifying potential factors associated with medication possession ratio. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney-Doyle, K.; Ventura Castellon, E.; Lindley, L.C. Factors associated with transitions to adult care among adolescents and young adults with medical complexity. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2024, 41, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, E.; Kocot, E.; Evers, S.; Sowada, C.; Pavlova, M. Do financial aspects affect care transitions in long-term care systems? A systematic review. Arch. Public. Health 2022, 80, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbalinda, S.N.; Bakeera-Kitaka, S.; Lusota, D.A.; Musoke, P.; Nyashanu, M.; Kaye, D.K. Transition to adult care: Exploring factors associated with transition readiness among adolescents and young people in adolescent ART clinics in Uganda. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.G.; Daher, A.; Barrera Ortiz, L.; Carreño-Moreno, S.; Hafez, H.S.R.; Jansen, A.M.; Rico-Restrepo, M.; Chaparro-Diaz, L. Rarecare: A policy perspective on the burden of rare diseases on caregivers in Latin America. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1127713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippo, E.M.; Talwalkar, J.S.; Harris, Z.M.; Butcher, J.; Nasr, S.Z. Transitions of care in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2022, 43, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Vogt, H.; Pettit, R.S. Educational initiative to increase knowledge for transition to adult care in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 28, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poamaneagra, S.C.; Plesca, D.-A.; Tataranu, E.; Marginean, O.; Nemtoi, A.; Mihai, C.; Gilca-Blanariu, G.-E.; Andronic, C.-M.; Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Diaconescu, S. A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237428

Poamaneagra SC, Plesca D-A, Tataranu E, Marginean O, Nemtoi A, Mihai C, Gilca-Blanariu G-E, Andronic C-M, Anchidin-Norocel L, Diaconescu S. A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237428

Chicago/Turabian StylePoamaneagra, Silvia Cristina, Doina-Anca Plesca, Elena Tataranu, Otilia Marginean, Alexandru Nemtoi, Catalina Mihai, Georgiana-Emmanuela Gilca-Blanariu, Cristiana-Mihaela Andronic, Liliana Anchidin-Norocel, and Smaranda Diaconescu. 2024. "A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237428

APA StylePoamaneagra, S. C., Plesca, D.-A., Tataranu, E., Marginean, O., Nemtoi, A., Mihai, C., Gilca-Blanariu, G.-E., Andronic, C.-M., Anchidin-Norocel, L., & Diaconescu, S. (2024). A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237428