Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

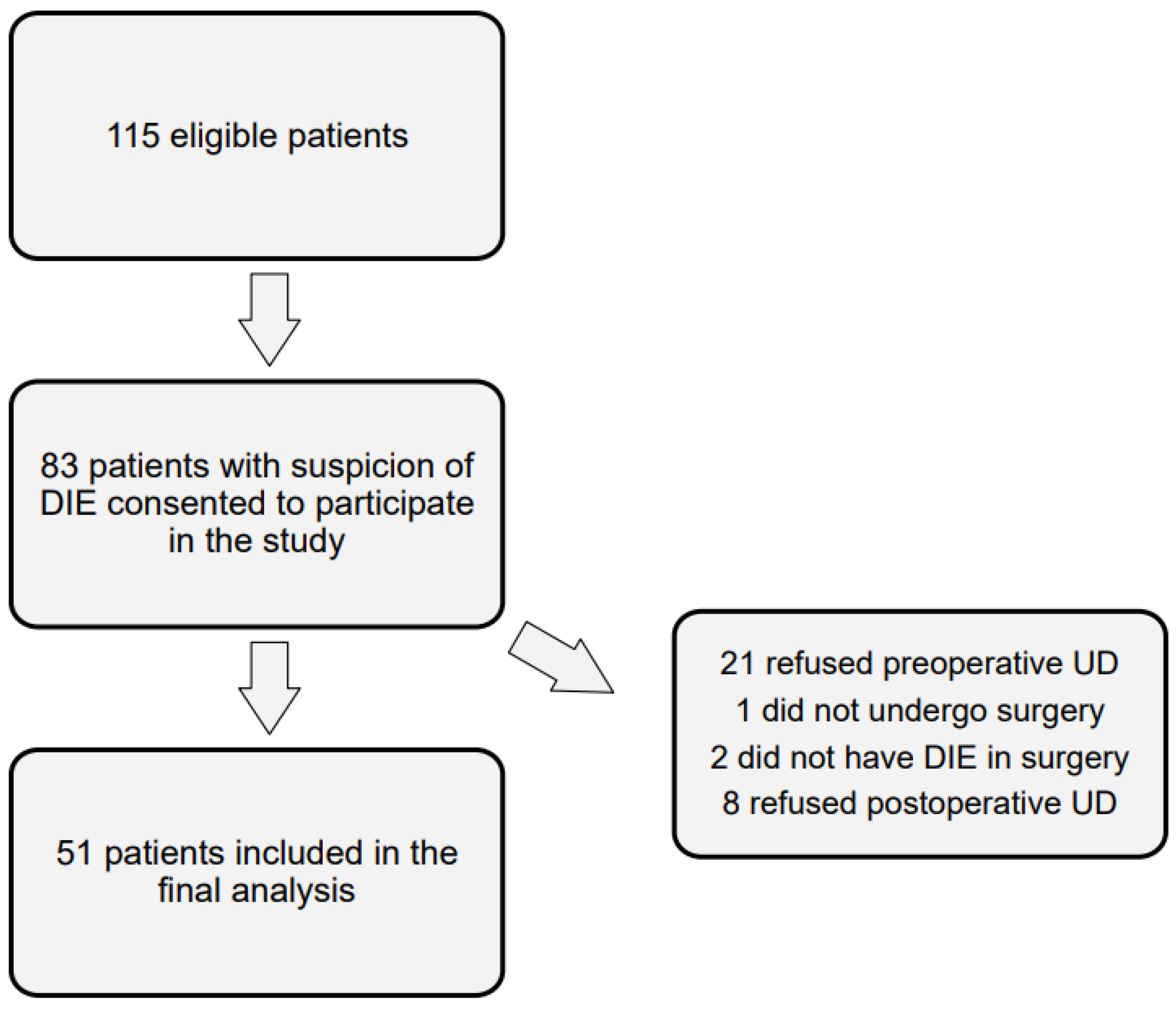

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aue-Aungkul, A.; Kietpeerakool, C.; Rattanakanokchai, S.; Galaal, K.; Temtanakitpaisan, T.; Ngamjarus, C.; Lumbiganon, P. Postoperative interventions for preventing bladder dysfunction after radical hysterectomy in women with early-stage cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD012863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Haya, N.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Maher, C. Perioperative interventions in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Resende Junior, J.A.D.; Crispi, C.P.; Cardeman, L.; Buere, R.T.; Fonseca, M.F. Urodynamic observations and lower urinary tract symptoms associated with endometriosis: A prospective cross-sectional observational study assessing women with deep infiltrating disease. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panel, P.; Huchon, C.; Estrade-Huchon, S.; Le Tohic, A.; Fritel, X.; Fauconnier, A. Bladder symptoms and urodynamic observations of patients with endometriosis confirmed by laparoscopy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serati, M.; Cattoni, E.; Braga, A.; Uccella, S.; Cromi, A.; Ghezzi, F. Deep endometriosis and bladder and detrusor functions in women without urinary symptoms: A pilot study through an unexplored world. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterza, R.M.; Uccella, S.; Serati, M.; Umek, W.; Wenzl, R.; Graf, A.; Ghezzi, F. Is the Deep Endometriosis or the Surgery the Cause of Postoperative Bladder Dysfunction? J. Minim. Invasive. Gynecol. 2022, 29, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ancona, C.; Haylen, B.; Oelke, M.; Abranches-Monteiro, L.; Arnold, E.; Goldman, H.; Hamid, R.; Homma, Y.; Marcelissen, T.; Rademakers, K.; et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villiger, A.S.; Fluri, M.M.; Hoehn, D.; Radan, A.; Kuhn, A. Cough-Induced Detrusor Overactivity-Outcome after Conservative and Surgical Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, D.; Mohr, S.; Nowakowski, L.; Mueller, M.D.; Kuhn, A. A prospective cohort trial evaluating sexual function after urethral diverticulectomy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 272, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Meuleman, C.; Demeyere, S.; Lesaffre, E.; Cornillie, F.J. Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometriosis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 55, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halis, G.; Mechsner, S.; Ebert, A.D. The diagnosis and treatment of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpi, E.; Ferrero, A.; Sismondi, P. Laparoscopic identification of pelvic nerves in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Surg. Endosc. 2004, 18, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffo, G.; Scopelliti, F.; Scioscia, M.; Ceccaroni, M.; Mainardi, P.; Minelli, L. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: Analysis of 436 cases. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Santulli, P.; Bazot, M.; Coutant, C.; Rouzier, R.; Darai, E. Preoperative evaluation of posterior deep-infiltrating endometriosis demonstrates a relationship with urinary dysfunction and parametrial involvement. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011, 18, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imboden, S.; Bollinger, Y.; Härmä, K.; Knabben, L.; Fluri, M.; Nirgianakis, K.; Mohr, S.; Kuhn, A.; Mueller, M.D. Predictive Factors for Voiding Dysfunction after Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubernard, G.; Rouzier, R.; David-Montefiore, E.; Bazot, M.; Darai, E. Urinary complications after surgery for posterior deep infiltrating endometriosis are related to the extent of dissection and to uterosacral ligaments resection. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008, 15, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.; Mimouni, M.; Oppenheimer, A.; Nyangoh Timoh, K.; du Cheyron, J.; Fauconnier, A. Systematic Nerve Sparing during Surgery for Deep-infiltrating Posterior Endometriosis Improves Immediate Postoperative Urinary Outcomes. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Dubernard, G.; Wafo, E.; Bellon, L.; Amarenco, G.; Belghiti, J.; Daraï, E. Evaluation of urinary dysfunction by urodynamic tests, electromyography and quality of life questionnaire before and after surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 179, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckstein, J.; Saridogan, E.; Ulrich, U.A.; Sillem, M.; Oppelt, P.; Schweppe, K.W.; Krentel, H.; Janschek, E.; Exacoustos, C.; Malzoni, M.; et al. The #Enzian classification: A comprehensive non-invasive and surgical description system for endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barbier, H.; Carberry, C.L.; Karjalainen, P.K.; Mahoney, C.K.; Galán, V.M.; Rosamilia, A.; Ruess, E.; Shaker, D.; Thariani, K. International Urogynecology consultation chapter 2 committee 3: The clinical evaluation of pelvic organ prolapse including investigations into associated morbidity/pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 2657–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, W.; Abrams, P.; Liao, L.; Mattiasson, A.; Pesce, F.; Spangberg, A.; Sterling, A.M.; Zinner, N.R.; van Kerrebroeck, P. Good urodynamic practices: Uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P. Bladder outlet obstruction index, bladder contractility index and bladder voiding efficiency: Three simple indices to define bladder voiding function. BJU Int. 1999, 84, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haylen, B.T.; De Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.; Robertson, C.; Mazzetta, C.; Keech, M.; Hobbs, F.; Fourcade, R.; Kiemeney, L.; Lee, C.; The UrEpik Study Group. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women in four centres. The UrEpik study. BJU Int. 2003, 92, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponholzer, A.; Temml, C.; Wehrberger, C.; Marszalek, M.; Madersbacher, S. The association between vascular risk factors and lower urinary tract symptoms in both sexes. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, K.; Nojiri, Y.; Osuga, Y.; Tange, C. Psychometric analysis of international prostate symptom score for female lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology 2009, 73, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.W.; Green, J.S.A. How international is the International Prostate Symptom Score? A literature review of validated translations of the IPSS, the most widely used self-administered patient questionnaire for male lower urinary tract symptoms. Low. Urin. Tract. Symptoms 2022, 14, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitta, T.; Mitsui, T.; Kanno, Y.; Chiba, H.; Moriya, K.; Nonomura, K. Postoperative detrusor contractility temporarily decreases in patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int. J. Urol. 2015, 22, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altpeter, E.; Burnand, B.; Capkun, G.; Carrel, R.; Cerutti, B.; Gassner, M.; Junker, C.; Lengeler, C.; Minder, C.; Rickenbach, M.; et al. Essentials of good epidemiological practice. Soz. Praventivmed 2005, 50, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Elm, E.V.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Strobe Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, A.; Gulumser, C.; Pandis, G.; Saridogan, E.; Cutner, A. Voiding dysfunction in women undergoing laparoscopic treatment for moderate to severe endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 2113–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dior, U.P.; Reddington, C.; Cheng, C.; Levin, G.; Healey, M. Urinary Function after Surgery for Deep Endometriosis: A Prospective Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 308–316.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 51) |

|---|---|

| Age, yrs, median (range) | 34.0 (25–51) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range) | 23.3 (17–35) |

| Nulligravida, n (%) | 36 (70.59) |

| Nullipara, n (%) | 47 (92.16) |

| Wish to have children, n (%) | 32 (62.75) |

| Under hormonal treatment, n (%) | 30 (58.82) |

| MRI, n (%) | 29 (56.86) |

| Previous endometriosis surgery, n (%) | 19 (37.25) |

| #Enzian score, n (%) | |

| Compartment A | 36 (70.59) |

| Compartment B | 44 (86.27) |

| Compartment C | 25 (49.02) |

| Compartment FI | 6 (11.76) |

| Compartment FA | 13 (25.49) |

| Compartment FU | 2 (3.92) |

| rASRM stage, n (%) | |

| Stage 1 | 2 (4) |

| Stage 2 | 9 (18) |

| Stage 3 | 12 (24) |

| Stage 4 | 27 (54) |

| Duration of surgery, min, median (range) | 234 (62–540) |

| Blood loss, ml, median (range) | 174 (10–800) |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | |

| Ureterolysis | 23 (45.10) |

| Resection rectovaginal septum | 41 (80.39) |

| Vaginal wall resection | 26 (50.98) |

| Resection uterosacral ligaments | 42 (82.35) |

| Pelvic wall resection | 25 (49.02) |

| Bowel resection | 18 (35.29) |

| Appendectomy | 8 (15.69) |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSOO) | 4 (7.84) |

| Hysterectomy | 10 (20) |

| Perioperative complication, n (%) | 2 (4) |

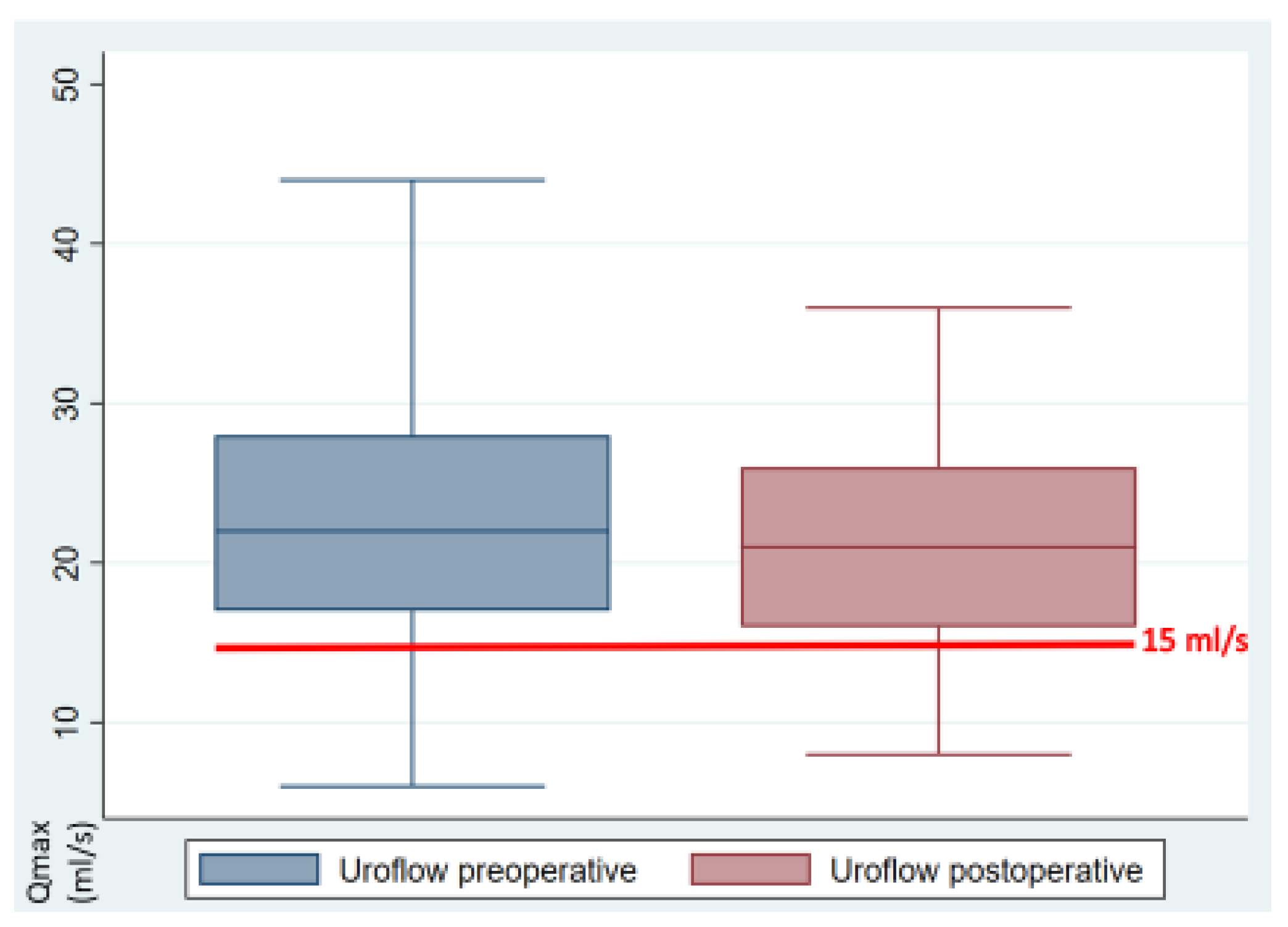

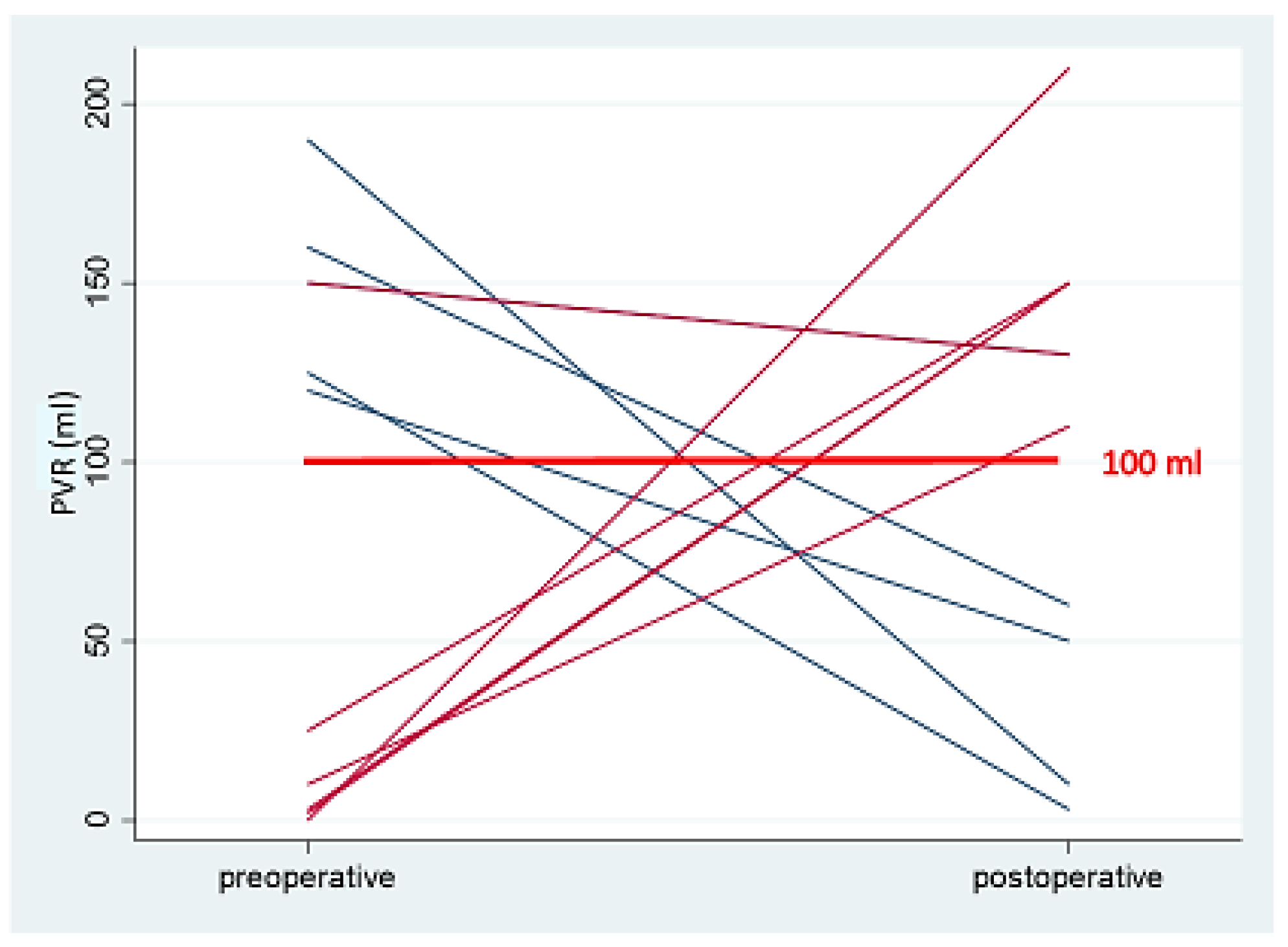

| Preop | Postop | p-Value | (95% Cl) | Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urodynamics | |||||

| Pressure flow | |||||

| Uroflow [mL/s] | 22.14 | 21.53 | 0.564 | (−1.5–2.71) | 0 |

| BCI | 130.38 | 116.63 | 0.046 | (0.23–27.27) | 10 |

| PVR [mL] | 26.1 | 33.59 | 0.390 | (−24.85–9.87) | 0 |

| Filling cystometry | |||||

| BV [mL] | 356.86 | 310.22 | 0.159 | (−18.89–112.16) | 2 |

| DO [yes/no] | 15.69% | 4% | 0.049 | (0.003–0.23) | 1 |

| MUCP [cmH2O] | 95.41 | 82.08 | 0.003 | (4.76–21.89) | 14 |

| Visual analog scale [0–10] | |||||

| Dysmenorrhea | 5.4 | 1.75 | <0.001 | (2.47–4.83) | 11 |

| CPP | 2.93 | 1.35 | <0.001 | (0.79–2.36) | 11 |

| Dyspareunia | 3.18 | 0.2 | <0.001 | (2.09–3.86) | 11 |

| Dyschezia | 3.18 | 1.05 | <0.001 | (1.04–3.21) | 11 |

| Dysuria | 1.08 | 0.53 | 0.109 | (−0.13–1.23) | 11 |

| IPSS [0–35] | 8.37 | 8.51 | 0.893 | (−2.35–2.05) | 10 |

| QoL | 1.32 | 1.29 | 0.922 | (−0.48–0.53) | 10 |

| Inc. emptying | 1.59 | 1.37 | 0.395 | (−0.3–0.74) | 10 |

| Frequency | 1.61 | 1.22 | 0.077 | (−0.04–0.82) | 10 |

| Intermittency | 1 | 1.49 | 0.079 | (−1.04–0.06) | 10 |

| Urgency | 0.95 | 0.59 | 0.117 | (−0.1–0.83) | 10 |

| Weak stream | 0.9 | 1.44 | 0.043 | (−1.06–−0.02) | 10 |

| Straining | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.467 | (−0.55–0.26) | 10 |

| Nocturia | 1.56 | 1.51 | 0.844 | (−0.45–0.55) | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villiger, A.-S.; Hoehn, D.; Ruggeri, G.; Vaineau, C.; Nirgianakis, K.; Imboden, S.; Kuhn, A.; Mueller, M.D. Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237367

Villiger A-S, Hoehn D, Ruggeri G, Vaineau C, Nirgianakis K, Imboden S, Kuhn A, Mueller MD. Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237367

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilliger, Anna-Sophie, Diana Hoehn, Giovanni Ruggeri, Cloé Vaineau, Konstantinos Nirgianakis, Sara Imboden, Annette Kuhn, and Michael David Mueller. 2024. "Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237367

APA StyleVilliger, A.-S., Hoehn, D., Ruggeri, G., Vaineau, C., Nirgianakis, K., Imboden, S., Kuhn, A., & Mueller, M. D. (2024). Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237367