Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease: Results from a Large Real-Life Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Treatment

2.2. Clinical Assessment at Baseline and During the Follow-Up

2.3. Endoscopy Assessment at Baseline and During the Follow-Up

2.4. Outcomes

- Mucosal healing, defined as SES-CD ≤ 2 in CD patients;

- Reduction of steroid use during the study (defined as the use of systemic or topic steroids);

- Maintenance of steroid-free remission during the study;

- Occurrence of any surgical procedure related to the disease in CD;

- UST optimization, defined as the reduction of the time between the injections from eight to four weeks) during follow-up;

- CRP, FC, and HBI variations during follow-up;

- Re-induction of remission, defined as re-induction with intravenous infusion of either ustekinumab 260, 390, or 520 mg, according to the weight per prescribing guidelines [53].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics (At 12 Months After Beginning UST Treatment)

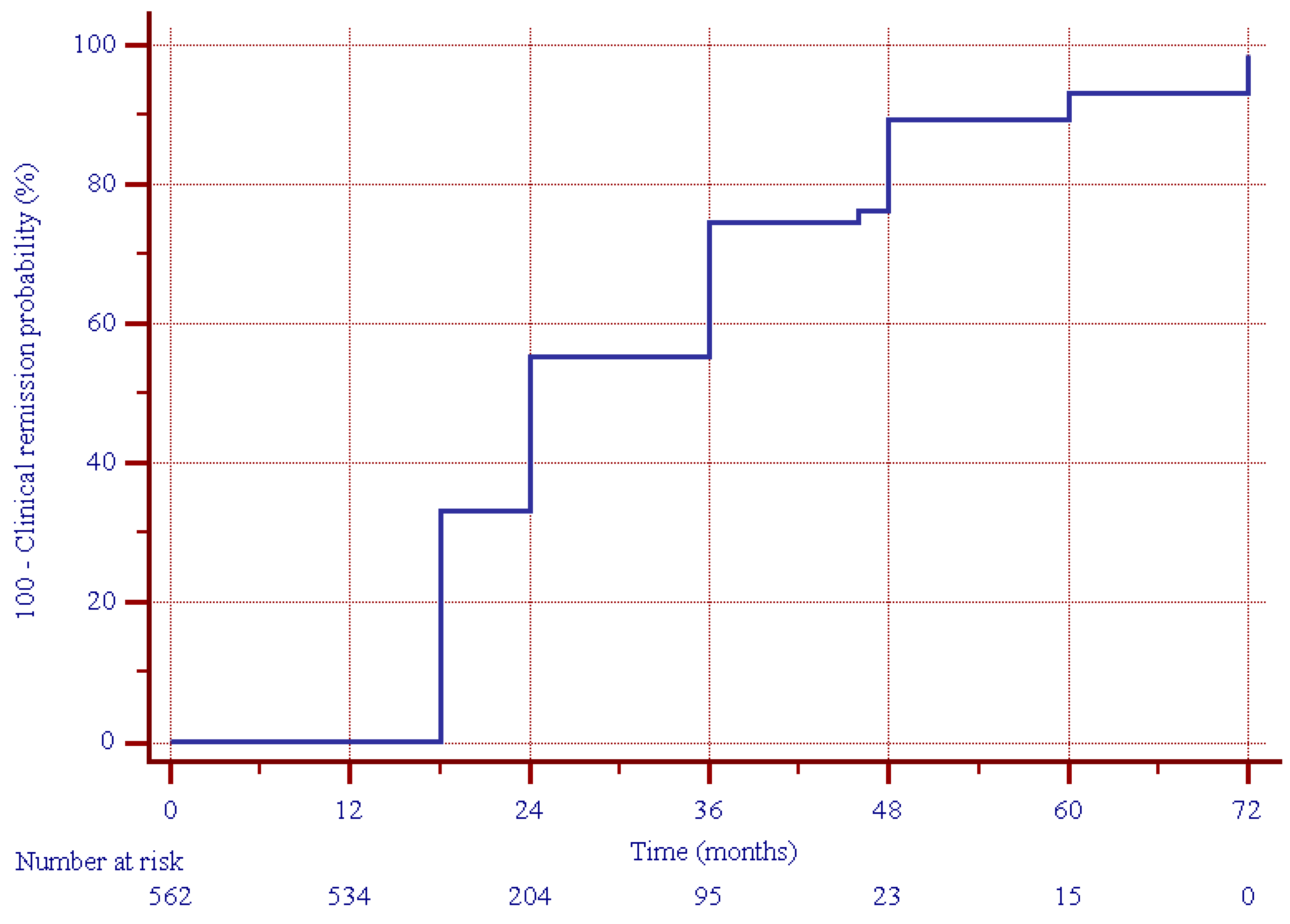

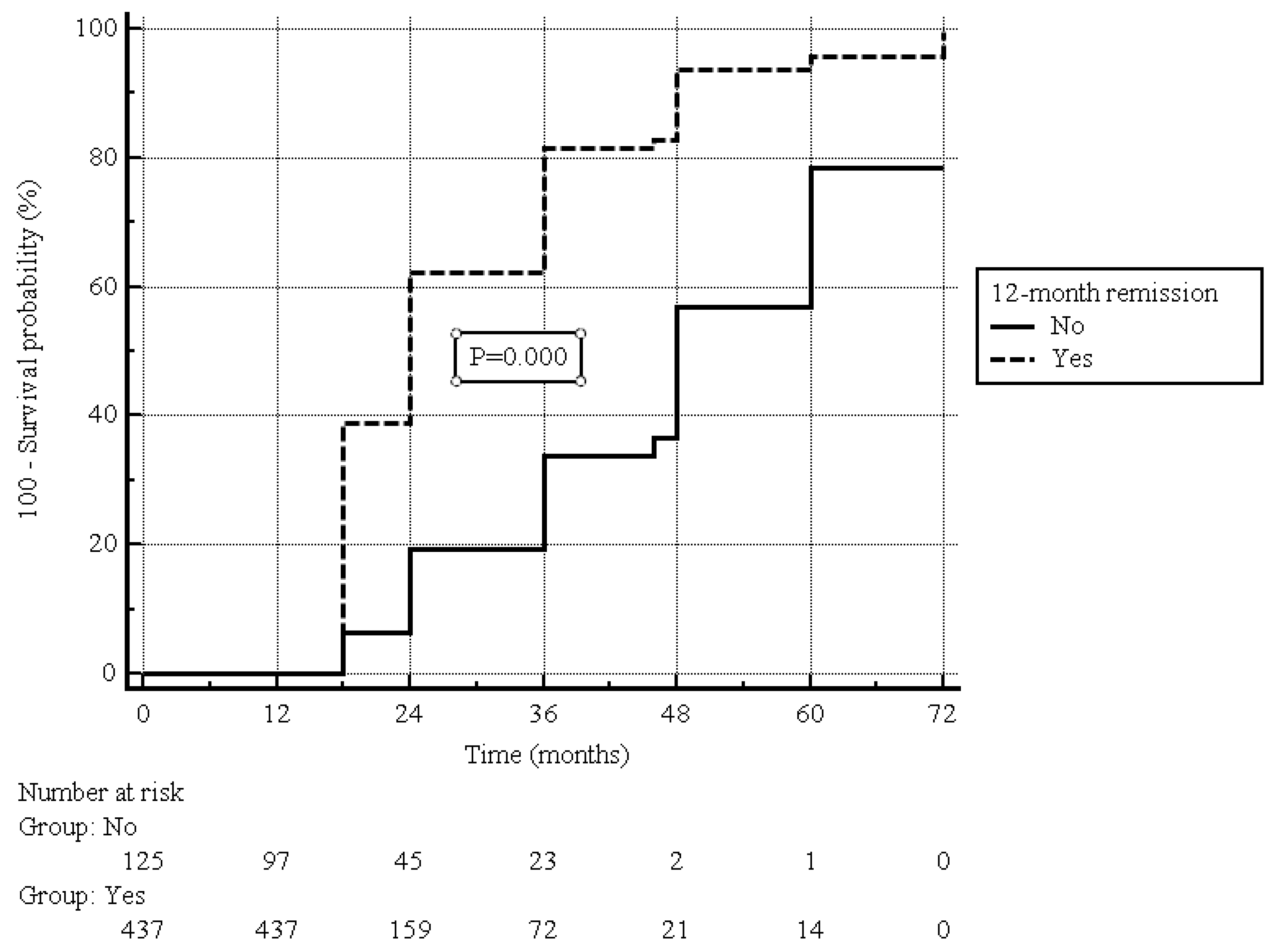

3.2. Primary Outcomes

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.4. Safety Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2012, 380, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molodecky, N.A.; Soon, I.S.; Rabi, D.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Ferris, M.; Chernoff, G.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Barkema, H.W.; et al. Based on systematic review, increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.R.; Lyons, M.; Plevris, N.; Jenkinson, P.W.; Bisset, C.; Burgess, C.; Din, S.; Fulforth, J.; Henderson, P.; Ho, G.T.; et al. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut 2019, 68, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, N.A.; Heap, G.A.; Green, H.D.; Hamilton, B.; Bewshea, C.; Walker, G.J.; Thomas, A.; Nice, R.; Perry, M.H.; Bouri, S.; et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease: A prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, F.; Noman, M.; Vermeire, S.; Van Assche, G.; D’Haens, G.; Carbonez, A.; Rutgeerts, P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.C.; Sandborn, W.J.; Khan, K.J.; Hanauer, S.B.; Talley, N.J.; Moayyedi, P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonovas, S.; Fiorino, G.; Allocca, M.; Lytras, T.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Biologic therapies and risk of infection and malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1385–1397.e1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.W.; Bowman, E.P.; McElwee, J.J.; Smyth, M.J.; Casanova, J.-L.; Cooper, A.M.; Cua, D.J. IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines: From discovery to targeted therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelara EMA. Product Information. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/h494.htm (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Zaghi, D.; Krueger, G.G.; Callis Duffin, K. Ustekinumab: A review in the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012, 11, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mocci, G.; Tursi, A.; Onidi, F.M.; Usai-Satta, P.; Pes, G.M.; Dore, M.P. Ustekinumab in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Evolving Paradigms. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Gasink, C.; Gao, L.L.; Blank, M.A.; Johanns, J.; Guzzo, C.; Sands, B.E.; Hanauer, S.B.; Targan, S.; Rutgeerts, P.; et al. Ustekinumab induction and maintenance therapy in refractory Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Gasink, C.; Jacobstein, D.; Lang, Y.; Friedman, J.R.; Blank, M.A.; Johanns, J.; Gao, L.L.; Miao, Y.; et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1946–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, S.B.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Gasink, C.; Jacobstein, D.; Zou, B.; Johanns, J.; Adedokun, O.J.; Sands, B.E.; Rutgeerts, P.; et al. IM-UNITI: Three-year Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of Ustekinumab Treatment of Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Rebuck, R.; Wang, Y.; Zou, B.; Adedokun, O.J.; Gasink, C.; Sands, B.E.; Hanauer, S.B.; Targan, S.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of Ustekinumab Treatment in Crohn’s Disease: The IM-UNITI Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 578–590.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iborra, M.; Beltrán, B.; Fernández-Clotet, A.; Gutiérrez, A.; Antolín, B.; Huguet, J.M.; De Francisco, R.; Merino, O.; Carpio, D.; García-López, S.; et al. Real-world short-term effectiveness of ustekinumab in 305 patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from the ENEIDA registry. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefferinckx, C.; Verstockt, B.; Gils, A.; Noman, M.; Van Kemseke, C.; Macken, E.; De Vos, M.; Van Moerkercke, W.; Rahier, J.F.; Bossuyt, P.; et al. Long-term Clinical Effectiveness of Ustekinumab in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Who Failed Biologic Therapies: A National Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemans, V.B.C.; Van der Meulen-de Jong, A.E.; Van der Woude, C.J.; Löwenberg, M.; Dijkstra, G.; Oldenburg, B.; de Boer, N.K.H.; van der Marel, S.; Bodelier, A.G.L.; Jansen, J.M.; et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn’s Disease: Results of the ICC Registry, a Nationwide Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.; Krisam, J.; Wehling, C.; Kloeters-Plachky, P.; Leopold, Y.; Belling, N.; Gauss, A. Ustekinumab: “Real-world” outcomes and potential predictors of non-response in treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, A.; Hallinen, T.; Af Björkesten, C.G.; Heikkinen, M.; Hirsi, E.; Kellokumpu, M.; Koskinen, I.; Moilanen, V.; Nielsen, C.; Nuutinen, H.; et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn’s disease: A nationwide real-life cohort study from Finland (FINUSTE). Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Gil Shitrit, A.; Ben-Ya’acov, A.; Siterman, M.; Waterman, M.; Hirsh, A.; Schwartz, D.; Zittan, E.; Adler, Y.; Koslowsky, B.; Avni-Biron, I.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab for induction of remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: A multicenter Israeli study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, D.; Daperno, M.; Fiorino, G.; Savarino, E.; Mosso, E.; Biancone, L.; Testa, A.; Sarpi, L.; Cappello, M.; Bodini, G.; et al. Real-life effectiveness of ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease patients with concomitant psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis: An IG-IBD study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2019, 51, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kaplan, G.G.; Dieleman, L.A.; Devlin, S.M.; Stern, N.; Kroeker, K.I.; Seow, C.H.; Leung, Y.; Novak, K.L.; et al. Clinical, endoscopic and radiographic outcomes with ustekinumab in medically-refractory Crohn’s disease: Real world experience from a multicentre cohort. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo González, L.; Valdés Delgado, T.; Vázquez Morón, J.M.; Laria, L.C.; Carnerero, E.L.; Maldonado Pérez, M.B.; Sánchez Capilla, D.; Pallarés Manrique, H.; Sáez Díaz, A.; Argüelles Arias, F.; et al. Grupo de Enfermedad Inflamatoria de Andalucía. Ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease: Real-world outcomes and predictors of response. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2022, 114, 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bacaksız, F.; Arı, D.; Gökbulut, V.; Öztürk, Ö.; Kayaçetin, E. One-year real life data of our patients with moderate-severe Crohn’s disease who underwent ustekinumab therapy. Scott. Med. J. 2021, 66, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaluso, F.S.; Fries, W.; Viola, A.; Costantino, G.; Muscianisi, M.; Cappello, M.; Guida, L.; Giuffrida, E.; Magnano, A.; Pluchino, D.; et al. Effectiveness of Ustekinumab on Crohn’s Disease Associated Spondyloarthropathy: Real-World Data from the Sicilian Network for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (SN-IBD). Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 1381–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Muscianisi, M.; Macaluso, F.S.; Ventimiglia, M.; Cappello, M.; Privitera, A.C.; Magnano, A.; Pluchino, D.; Magrì, G.; Ferracane, C.; et al. “Sicilian Network for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SN-IBD)”Ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease: Real-world outcomes from the Sicilian network for inflammatory bowel diseases. JGH Open 2021, 5, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Gravina, A.G.; Cuomo, A.; Mucherino, C.; Sgambato, D.; Facchiano, A.; Granata, L.; Priadko, K.; Pellegrino, R.; de Filippo, F.R.; et al. Efficacy of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with Crohn’s disease with failure to previous conventional or biologic therapy: A prospective observational real-life study. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 115, S522–S523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, S.; Asano, T.; Nagano, K.; Tsuchiya, H.; Takagishi, M.; Tsujioka, S.; Miura, N.; Matsumoto, T. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease: Interim results of post-marketing surveillance in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 3069–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Peng, X.; Zhao, J.Z.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.W.; Sun, H.T.; Hu, P.; Zhi, M. Ustekinumab trough concentration affects clinical and endoscopic outcomes in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease: A Chinese real-world study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tursi, A.; Mocci, G.; Cuomo, A.; Allegretta, L.; Aragona, G.; Colucci, R.; Della Valle, N.; Ferronato, A.; Forti, G.; Gaiani, F.; et al. Real-life efficacy and safety of ustekinumab as second- or third-line therapy in Crohn’s disease: Results from a large Italian cohort study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scribano, M.L.; Aratari, A.; Neri, B.; Bezzio, C.; Balestrieri, P.; Baccolini, V.; Falasco, G.; Camastra, C.; Pantanella, P.; Monterubbianesi, R.; et al. Effectiveness of ustekinumab in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease: A multicentre real-life study in Italy. Therap Adv. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15, 17562848211072412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylisaukko-Oja, T.; Puttonen, M.; Jokelainen, J.; Koivusalo, M.; Tamminen, K.; Torvinen, S.; Voutilainen, M. Dose-escalation of adalimumab, golimumab or ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel diseases: Characterisation and implications in real-life clinical practice. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Carlini, L.E.; Duley, C.; Garrett, A.; Annis, K.; Wagnon, J.; Dalal, R.; Scoville, E.; Beaulieu, D.; Schwartz, D.; et al. A Single Center Experience with Long-Term Ustekinumab Use and Reinduction in Patients with Refractory Crohn Disease. Crohns Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.S.; Chebli, J.M.F.; Queiroz, N.S.F.; Damião, A.O.M.C.; de Azevedo, M.F.C.; Chebli, L.A.; Bertges, E.R.; Alves Junior, A.J.T.; Ambrogini Junior, O.; da Silva, B.L.P.S.; et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab in bio-naïve and bio-experienced anti-tumor necrosis factor patients with Crohn’s disease: A real-world multicenter Brazilian study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forss, A.; Clements, M.; Myrelid, P.; Strid, H.; Söderman, C.; Wagner, A.; Andersson, D.; Hjelm, F.; PROSE SWIBREG study group; Olén, O.; et al. Ustekinumab Is Associated with Real-World Long-Term Effectiveness and Improved Health-Related Quality of Life in Crohn’s Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, M.; Ihara, Y.; Tominaga, N.; Takedomi, H.; Tsuruoka, N.; Akutagawa, T.; Yukimoto, T.; Kawasaki, K.; Umeno, J.; Torisu, T.; et al. Predictive factors of the clinical efficacy of ustekinumab in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease: Tertiary centers experience in Japan. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2023, 38, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Deza, D.; Lamuela-Calvo, L.J.; Gomollón, F.; Arbonés-Mainar, J.M.; Caballol, B.; Gisbert, J.P.; Rivero, M.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, E.; Arias García, L.; Gutiérrez Casbas, A.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Elderly Patients with Crohn’s Disease: Real World Evidence From the ENEIDA Registry. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wils, P.; Bouhnik, Y.; Michetti, P.; Flourie, B.; Brixi, H.; Bourrier, A.; Allez, M.; Duclos, B.; Serrero, M.; Buisson, A.; et al. Groupe d’Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Long-term efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in 122 refractory Crohn’s disease patients: A multicentre experience. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kaplan, G.G.; Dieleman, L.A.; Devlin, S.M.; Stern, N.; Kroeker, K.I.; Seow, C.H.; Leung, Y.; Novak, K.L.; et al. Long-term maintenance of clinical, endoscopic, and radiographic response to Ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: Realworld experience from a multicenter cohort study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebli, J.M.F.; Parra, R.S.; Flores, C.; Moraes, A.C.; Nones, R.B.; Gomes, T.N.F.; Perdomo, A.M.B.; Scapini, G.; Zaltman, C. Effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab for moderate to severely active Crohn’s disease: Results from an early access program in Brazil. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regime di Rimborsabilità e Prezzo, a Seguito di Nuove Indicazioni Terapeutiche, del Medicinale per uso Umano “Stelara”. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana del 03.09.2018; Serie Generale-n. 204: 15-18. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2018-09-03&atto.codiceRedazionale=18A05714&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Gomollón, F.; Dignass, A.; Annese, V.; Tilg, H.; Van Assche, G.; Lindsay, J.O.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Cullen, G.J.; Daperno, M.; Kucharzik, T.; et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; Hendy, P.A.; Smith, P.J.; Limdi, J.K.; Hayee, B.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Parkes, G.C.; Selinger, C.; et al. Britich Society of Gastroenterology Consensus Guidelines on the management of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Adults. Gut 2019, 68, S1–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsangi, J.; Silverberg, M.S.; Vermeire, S.; Colombel, J.F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006, 55, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, W.R. Predicting the Crohn’s Disease activity index from the Harvey–Bradshaw Index. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006, 12, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daperno, M.; D’Haens, G.; Van Assche, G.; Baert, F.; Bulois, P.; Maunoury, V.; Sostegni, R.; Rocca, R.; Pera, A.; Gevers, A.; et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: The SES-CD. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2004, 60, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskovitz, D.N.; Daperno, M.; Van Assche, G. Defining and validating cut-offs for the simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, S1097. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgeerts, P.; Geboes, K.; Vantrappen, G.; Vantrappen, G.; Beyls, J.; Kerremans, R.; Hiele, M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Reinisch, W.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Kornbluth, A.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Lichtiger, S.; D’Haens, G.; Diamond, R.H.; Broussard, D.L.; et al. SONIC Study Group. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelara (Ustekinumab) [Package Insert], in U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. 2016. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761044lbl.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Macaluso, F.S.; Maida, M.; Ventimiglia, M.; Ventimiglia, M.; Cottone, M.; Orlando, A. Effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in real-life experiences: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustekinumab reintroduction: Week 16 results and baseline response analysis from the POWER study in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 19, 12–13.

- Schmitt, H.; Billmeier, U.; Dieterich, W.; Rath, T.; Sonnewald, S.; Reid, S.; Hirshmann, S.; Hildner, K.; Waldner, M.J.; Mudter, J.; et al. Expansion of IL-23 receptor bearing TNFR2+ T cells is associated with molecular resistance to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2019, 68, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.Y.; Lund, J.L.; Funk, M.J.; Hudgens, M.G.; Lewis, J.D.; Kappelman, M.D.; SPARC IBD Investigators. Utilization of Treat-to-Target Monitoring Colonoscopy After Treatment Initiation in the US-Based Study of a Prospective Adult Research Cohort With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 1638–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Ali, O.; Cross, R.K. Assessing Progression of Biologic Therapies Based on Smoking Status in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male Sex | 312 (55.5) |

|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age at diagnosis, years | 45 (32–57) |

| Current smokers | 150 (26.7) |

| Previous appendectomy | 141 (25.1) |

| Previous surgery for CD | 312 (55.5) |

| Montreal classification | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |

| 17–39 | 225 (40.0) |

| ≥40 | 337 (60.0) |

| Location | |

| Isolated ileal disease | 199 (35.4) |

| Isolated colonic disease | 81 (14.4) |

| Ileocolonic disease | 282 (50.2) |

| Concomitant perianal disease | 71 (12.6) |

| Behavior | |

| Non stricturing, non-penetrating | 205 (36.5) |

| Stricturing | 267 (47.5) |

| Penetrating | 90 (16.0) |

| Median (IQR) disease duration, years | 11 (7–19) |

| Failure of other biologics Naïve | 488 (86.8) 74 (13.2) |

| Steroid-free | 519 (92.3) |

| Concomitant medications | |

| Mesalazine | 316 (56.2) |

| Azathioprine Median (IQR) fecal calprotectin (µg/g) | 21 (3.7) 148 (80–244) |

| Median (IQR) CRP (mg/L) | 3 (1–5) |

| Median (IRQ) HBI | 4 (2–5) |

| Median (IRQ) SES-CD (130 pts) | 5 (2–8) |

| Rutgeerts score (110 pts) | 1 (1–2) |

| Clinical response | 125 (22.2) |

| Clinical remission | 437 (77.8) |

| Total | Remission | No Remission | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 562 | 450 (80.1) | 112 (19.9) | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 250 (44.5) | 198 (79.2) | 52 (20.8) | Ref. | ||||||

| Male | 312 (55.5) | 252 (80.8) | 60 (19.2) | 0.99 | 0.83–1.20 | 0.954 | 0.96 | 0.80–1.16 | 0.695 | |

| Current smokers | ||||||||||

| No | 412 (73.3) | 332 (80.6) | 80 (19.4) | |||||||

| Yes | 150 (26.7) | 118 (78.7) | 32 (21.3) | 0.88 | 0.72–1.08 | 0.131 | 0.87 | 0.70–1.08 | 0.201 | |

| Previous surgery for CD | ||||||||||

| No | 250 (44.5) | 201 (44.7) | 49 (43.7) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 312 (55.5) | 249 (55.3) | 63 (56.2) | 0.98 | 0.82–1.18 | 0.860 | 1.05 | 0.87–1.27 | 0.622 | |

| Previous appendectomy | ||||||||||

| No | 421 (74.9) | 348 (82.7) | 73 (17.3) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 141 (25.1) | 102 (72.3) | 39 (27.7) | 0.94 | 0.76–1.17 | 0.499 | 0.90 | 0.85–1.46 | 0.087 | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18–39 | 225 (40.0) | 185 (82.2) | 40 (17.8) | Ref. | ||||||

| ≥40 | 337 (60.0) | 256 (78.6) | 72 (21.4) | 0.88 | 0.73–1.07 | 0.100 | 0.86 | 0.71–1.04 | 0.129 | |

| Location | ||||||||||

| Other | 280 (49.8) | 218 (77.9) | 62 (22.1) | Ref. | ||||||

| Ileocolonic | 282 (50.2) | 232 (82.3) | 50 (17.7) | 1.06 | 0.88–1.28 | 0.401 | 1.03 | 0.86–1.25 | 0.712 | |

| Behavior | ||||||||||

| Non stricturing, non-penetrating | 205 (36.5) | 167 (81.5) | 38 (18.5) | Ref. | ||||||

| Stricturing/penetrating | 357 (63.5) | 283 (79.3) | 74 (20.7) | 0.92 | 0.75–1.11 | 0.258 | 0.91 | 0.75–1.11 | 0.362 | |

| Naïve to biologics | ||||||||||

| No | 488 (86.8) | 397 (88.2) | 91 (81,2) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 74 (13.2) | 53 (11.8) | 21 (18.8) | 0.98 | 0.73–1.31 | 0.873 | 0.94 | 0.71–1.401 | 0.241 | |

| Non-response to biologics | ||||||||||

| No | 229 (40.7) | 183 (79.9) | 46 (20.1) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 333 (59.3) | 267 (80.2) | 66 (19.8) | 1.15 | 0.95–1.38 | 0.067 | 1.27 | 1.03–1.56 | 0.028 | |

| Clinical response | ||||||||||

| No | 62 (11.0) | 15 (3.3) | 47 (42.0) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 500 (89.0) | 435 (96.7) | 65 (58.0) | 3.55 | 2.64–4.78 | 0.000 | 1.44 | 0.725–2.88 | 0.295 | |

| Clinical remission | ||||||||||

| No | 125 (22.2) | 33 (7.3) | 92 (82.1) | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 437 (77.8) | 417 (92.7) | 20 (17.9) | 3.15 | 2.50–3.97 | 0.000 | 2.95 | 1.82–4.78 | 0.000 | |

| Group A (437/562) | Group B (125/562) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Adverse Events (AE) | 6 (1.4%) | 2 (1.6%) | ns |

Mild-Moderate AE

| 1 (0.2%) 1 (0.2%) 1 (0.2%) 1 (0.2%) - - | - - - - 1 (0.8%) 1 (0.8%) | ns ns ns ns ns ns |

Severe AE

| 1 (0.2%) | - | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mocci, G.; Tursi, A.; Scaldaferri, F.; Napolitano, D.; Pugliese, D.; Capobianco, I.; Bartocci, B.; Blasi, V.; Savarino, E.V.; Maniero, D.; et al. Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease: Results from a Large Real-Life Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237192

Mocci G, Tursi A, Scaldaferri F, Napolitano D, Pugliese D, Capobianco I, Bartocci B, Blasi V, Savarino EV, Maniero D, et al. Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease: Results from a Large Real-Life Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237192

Chicago/Turabian StyleMocci, Giammarco, Antonio Tursi, Franco Scaldaferri, Daniele Napolitano, Daniela Pugliese, Ivan Capobianco, Bianca Bartocci, Valentina Blasi, Edoardo V. Savarino, Daria Maniero, and et al. 2024. "Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease: Results from a Large Real-Life Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237192

APA StyleMocci, G., Tursi, A., Scaldaferri, F., Napolitano, D., Pugliese, D., Capobianco, I., Bartocci, B., Blasi, V., Savarino, E. V., Maniero, D., Redavid, C., Lorenzon, G., Cuomo, A., Donnarumma, L., Gravina, A. G., Pellegrino, R., Bodini, G., Pasta, A., Marzo, M., ... Papa, A. (2024). Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease: Results from a Large Real-Life Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237192