Drug-Related Problems and Sick Day Management Considerations for Medications that Contribute to the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Describe the most common DRPs identified by pharmacists, including medications that require sick day management (SADMANS).

- Describe the recommendations made by pharmacists to aged care staff (GPs and nurses), including recommendations on withholding medications during an acute illness.

- Describe GP uptake of pharmacist recommendations during RMMRs.

2. Materials and Methods

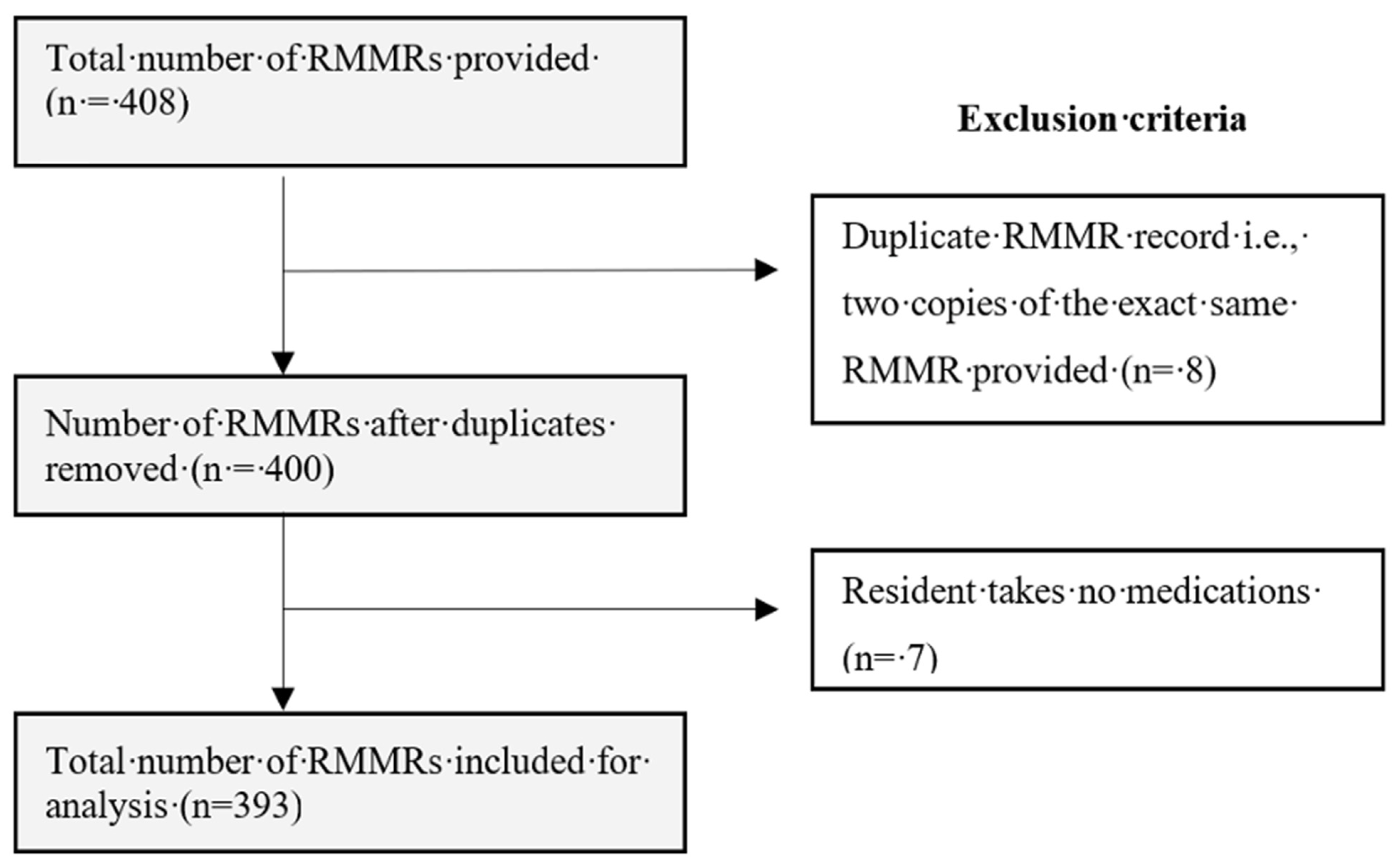

2.1. Data Collection, Study Population and Sampling

2.2. Data Extraction and Coding

‘…taking fludrocortisone and carbamazepine both may reduce bone mineral density. Consider assessing the patient’s bone mineral density if not done recently to ascertain whether they might benefit from an antiresorptive therapy.’

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Drug-Related Problems and Recommendations Found in Non-SADMANS Medications

3.2. Drug-Related Problems Found in SADMANS Medications

3.3. Pharmacist Recommendations and Rate of Acceptance

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorj, G.; Nair, N.P.; Bereznicki, L.; Kelly, T.-L.; Pratt, N.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Andrade, A.; Rowett, D.; Whitehouse, J.; Widagdo, I.; et al. Risk factors predictive of adverse drug events and drug-related falls in aged care residents: Secondary analysis from the ReMInDAR trial. Drugs Aging 2023, 40, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, R.; Ellett, L.M.K.; Semple, S.; Roughead, E.E. The Extent of Medication-Related Hospital Admissions in Australia: A Review from 1988 to 2021. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, P.; Cherney, D.; Gilbert, R.E.; Senior, P. Chronic Kidney Disease in Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, S201–S209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, W.H.; Castelino, R.L.; Wimmer, B.C.; Zaidi, S.T.R. Inappropriate prescribing in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of prevalence, associated clinical outcomes and impact of interventions. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 71, e12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acute kidney injury in Australia A first national snapshot. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-kidney-disease/acute-kidney-injury-in-australia/summary (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Duong, H.; Tesfaye, W.; Van, C.; Sud, K.; Truong, M.; Krass, I.; Castelino, R.L. Sick day management in people with chronic kidney disease: A scoping review. J. Nephrol. 2022, 36, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea-Henry, T.N.; Baird-Gunning, J.; Petzel, E.; Roberts, D.M. Medication management on sick days. Aust. Prescr. 2017, 40, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.E.; Dhaliwal, K.; McMurtry, E.; Donald, T.; Lamont, N.; Benterud, E.; Kung, J.Y.; Robertshaw, S.; Verdin, N.; Drall, K.M.; et al. Sick Day Medication Guidance for People with Diabetes, Kidney Disease, or Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Scoping Review. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for pharmacists providing Residential Medication Management Review (RMMR) and Quality Use of Medicines (QUM) services. Available online: https://my.psa.org.au/s/article/guidelines-for-qum-services (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Gudi, S.K.; Kashyap, A.; Chhabra, M.; Rashid, M.; Tiwari, K.K. Impact of pharmacist-led home medicines review services on drug-related problems among the elderly population: A systematic review. Epidemiol Health 2019, 41, e2019020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.Q.; Tay, A.H.P.; Khoo, R.S.Y.; Goh, B.K.; Lo, P.F.L.; Lim, C.J.F. Effectiveness of Medication Review in Improving Medication Knowledge and Adherence in Primary Care Patients. Proc. Singap. Healthc. 2014, 23, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinks, T.H.A.M.; Egberts, T.C.G.; de Lange, T.M.; de Koning, F.H.P. Pharmacist-Based Medication Review Reduces Potential Drug-Related Problems in the Elderly. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD-11 Coding Tool Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (MMS). Available online: https://icd.who.int/ct11/icd11_mms/en/release (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Charlson Comorbidity Index. Available online: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3917/charlson-comorbidity-index-cci (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Williams, M.; Peterson, G.M.; Tenni, P.C.; Bindoff, I.K.; Stafford, A.C. DOCUMENT: A system for classifying drug-related problems in community pharmacy. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012, 34, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basger, B.J.; Moles, R.J.; Chen, T.F. Application of drug-related problem (DRP) classification systems: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 70, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenberger, P.M.; Lampert, M.L.; Kahmann, I.V.; van Mil, J.W.F.; Hersberger, K.E. Classification of drug-related problems with new prescriptions using a modified PCNE classification system. Pharm. World Sci. 2010, 32, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishtala, P.S.; Hilmer, S.N.; McLachlan, A.J.; Hannan, P.J.; Chen, T.F. Impact of Residential Medication Management Reviews on Drug Burden Index in Aged-Care Homes. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruchelvam, K.; Hasan, S.S.; Wong, P.S.; Kairuz, T. Residential Aged Care Medication Review to Improve the Quality of Medication Use: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, e1–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDerby, N.C.; Kosari, S.; Bail, K.S.; Shield, A.J.; Peterson, G.; Thorpe, R.; Naunton, M. The role of a residential aged care pharmacist: Findings from a pilot study. Australas. J. Ageing 2020, 39, e466–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.Y.H.; Wang, K.N.; Sluggett, J.K.; Ilomäki, J.; Hilmer, S.N.; Corlis, M.; Bell, J.S. Process, impact and outcomes of medication review in Australian residential aged care facilities: A systematic review. Australas. J. Ageing 2019, 38, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluggett, J.K.; Ilomäki, J.; Seaman, K.L.; Corlis, M.; Bell, J.S. Medication management policy, practice and research in Australian residential aged care: Current and future directions. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 116, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.T.; Etherton-Beer, C.D.; Clifford, R.M.; Burrows, S.; Eames, M.; Potter, K. Deprescribing in frail older people—Do doctors and pharmacists agree? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2016, 12, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luymes, C.H.; van der Kleij, R.M.J.J.; Poortvliet, R.K.E.; de Ruijter, W.; Reis, R.; Numans, M.E. Deprescribing Potentially Inappropriate Preventive Cardiovascular Medication:Barriers and Enablers for Patients and General Practitioners. Ann. Pharmacother. 2016, 50, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, H.W.; Etherton-Beer, C.; Page, A.; McLachlan, A.J.; Lo, S.Y.; Naganathan, V.; Kearney, L.; Hilmer, S.N.; Comans, T.; Mangin, D.; et al. Deprescribing for older people living in residential aged care facilities: Pharmacist recommendations, doctor acceptance and implementation. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 107, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dills, H.; Shah, K.; Messinger-Rapport, B.; Bradford, K.; Syed, Q. Deprescribing Medications for Chronic Diseases Management in Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 923–935.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, H.; Tesfaye, W.; Van, C.; Sud, K.; Castelino, R.L. Hospitalisation Due to Community-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury and the Role of Medications: A Retrospective Audit. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, S.J.; Scherpbier, N.D.; Peters, H.J.G.; Uijen, A.A. Preventing acute kidney injury in high-risk patients by temporarily discontinuing medication—An observational study in general practice. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Information (n = 393) | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) age (years) | 85.2 ± 8.1 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 249 (63.3%) |

| Male | 139 (35.4%) |

| Unidentifiable | 5 (1.3%) |

| Remoteness (%) | |

| Major cities | 274 (69.7%) |

| Regional | 118 (30.0%) |

| Not available | 1 (0.3%) |

| Mean (±SD) number of medical conditions | 8.4 ± 2.8 |

| Top five medical conditions [n (%)] | |

| 630 (19.1%) |

| 532 (16.1%) |

| 382 (11.6%) |

| 267 (8.1%) |

| 249 (7.5%) |

| Mean (±SD) number of regular medications | 9.3 ± 4.1 |

| Top five regular medications used [n (%)] | |

| 1172 (32.3%) |

| 840 (23.2%) |

| 665 (18.3%) |

| 215 (5.9%) |

| 167 (4.6%) |

| Mean (±SD) number of PRN medications | 2.8 ± 2.3 |

| Top five PRN medications used [n (%)] | |

| 362 (33.2%) |

| 356 (32.7%) |

| 107 (9.8%) |

| 85 (7.8%) |

| 58 (5.3%) |

| Mean (±SD) CCI score | 5.4 ± 1.7 |

| Drug Group | Proportion of DRPs (n%) | Types of Problems Found (n) | Most Common Recommendation Made by Pharmacists for the Type of Problem (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nervous system | 362 (38.5%) | Toxicity or ADR (113) | Dose decrease (27) |

| Drug selection (100) | Drug change: cease (28) | ||

| Undertreated (49) | Other changes to therapy (7) | ||

| Over- or underdose (54) | Dose decrease (25) | ||

| Compliance (12) | Drug formulation change (5) | ||

| Monitoring (7) | Monitoring: laboratory test (6) | ||

| Not classifiable (19) | Refer to prescriber (5) | ||

| Non-clinical (8) | Non-clinical (6) | ||

| Alimentary tract and metabolism | 301 (32.0%) | Drug selection (75) | Drug change: cease (18) |

| Undertreated (48) | Dose increase (12) | ||

| Toxicity or ADR (46) | Dose decrease (12) | ||

| Over- or underdose (56) | Dose decrease (24) | ||

| Monitoring (25) | Monitoring: laboratory test (24) | ||

| Compliance (24) | Drug formulation change (11) | ||

| Not classifiable (14) | Drug change: cease (6) | ||

| Non-clinical (13) | Information to nursing staff (7) | ||

| Cardiovascular system | 104 (11.1%) | Toxicity or ADR (47) | Monitoring: laboratory test (8) Drug change: cease (4) Dose decrease (1) |

| Over- or underdose (17) | Dose decrease (7) | ||

| Drug selection (19) | Drug change: cease and initiate (6) | ||

| Monitoring (11) | Monitoring: laboratory test (8) | ||

| Not classifiable (4) | Monitoring: non-laboratory test (1) Dose frequency/schedule change (1) Other changes to therapy (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Undertreated (4) | Drug change: initiate (3) | ||

| Compliance (2) | Dose frequency/schedule change (1) Other change to therapy (1) | ||

| Blood and blood-forming organs | 48 (5.1%) | Toxicity or ADR (17) | Monitoring: laboratory test (10) |

| Drug selection (10) | Drug change: cease and initiate (4) | ||

| Over- or underdose (9) | Review prescribed medicine (2) Dose increase (2) | ||

| Monitoring (5) | Monitoring: laboratory test (4) | ||

| Undertreated (5) | Drug change: initiate (4) | ||

| Compliance (1) | Information to nursing staff (1) | ||

| Non-clinical (1) | Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Musculoskeletal system | 45 (4.8%) | Undertreated (19) | Drug change: initiate (11) |

| Drug selection (8) | Review prescribed medicine (4) | ||

| Toxicity or ADR (5) | Monitoring: laboratory test (3) | ||

| Monitoring (3) | Monitoring: laboratory test (3) | ||

| Over- or underdose (3) | Dose increase (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) Refer to prescriber (1) | ||

| Not classifiable (3) | Monitoring: laboratory test (2) | ||

| Compliance (2) | Refer to prescriber (1) Education/counselling session (1) | ||

| Non-clinical (2) | Non-clinical (2) |

| Drug Group | Proportion of DRPs (n%) | Types of Problems Found (n) | Most Common Recommendation for the Type of Problem (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylureas | 7 (3.7%) | Drug selection (4) | Drug change: cease and initiate (2) Drug formulation change (2) |

| Toxicity (2) | Drug change: cease and initiate (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Over- or underdose (1) | Monitoring: laboratory test (1) | ||

| ACEis | 18 (9.4%) | Toxicity (9) | Monitoring: laboratory test (5) |

| Monitoring (3) | Monitoring: laboratory test (2) | ||

| Not classifiable (2) | Dose decrease (1) Monitoring: non-laboratory test (1) | ||

| Over- or underdose (2) | Dose decrease (2) | ||

| Drug selection (1) | Drug change: cease and initiate (1) | ||

| Undertreated (1) | Drug change: initiate (1) | ||

| Diuretics | 65 (34.0%) | Toxicity (32) | Monitoring: laboratory test (21) |

| Monitoring (10) | Monitoring: laboratory test (9) | ||

| Drug selection (10) | Review prescribed medicine (4) | ||

| Over- or underdose (7) | Dose decrease (2) Non-clinical (2) | ||

| Not classifiable (2) | Dose decrease (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Undertreated (3) | Monitoring: non-laboratory test (1) Dose decrease (1) Drug change: initiate (1) | ||

| Compliance (1) | Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Metformin | 41 (21.5%) | Monitoring (12) | Monitoring: laboratory test (9) |

| Toxicity (10) | Dose decrease (6) | ||

| Drug selection (8) | Drug change: combination formulation (4) | ||

| Over- or underdose (7) | Dose decrease (3) | ||

| Undertreated (3) | Dose decrease (1) Drug change: initiate (1) Monitoring: laboratory test (1) | ||

| Not classifiable (1) | Monitoring: laboratory test (1) | ||

| ARBs | 22 (11.5%) | Toxicity (12) | Monitoring: non-laboratory test (5) |

| Monitoring (5) | Monitoring: laboratory test (3) | ||

| Undertreated (2) | Monitoring: non-laboratory test (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| Drug selection (1) | Dose decrease (1) | ||

| Over- or underdose (1) | Drug chance: cease (1) | ||

| Non-clinical (1) | Non-clinical (1) | ||

| NSAIDs | 37 (19.4%) | Toxicity (17) | Monitoring: laboratory test (9) |

| Drug selection (10) | Review prescribed medicine (4) | ||

| Undertreated (4) | Drug change: initiate (4) | ||

| Monitoring (2) | Monitoring: laboratory test (1) | ||

| Non-clinical (2) | Non-clinical (2) | ||

| Over- or underdose (2) | Dose decrease (1) Review prescribed medicine (1) | ||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1 (0.5%) | Undertreated (1) | Monitoring: laboratory test (1) |

| Pharmacist Recommendation | Medication Group (Non-SADMANS/SADMANS) | Recommendation Accepted | Other Recommendation Provided | Recommendation Rejected | No Response to Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose decrease | Non-SADMANS | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| SADMANS | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dose increase | Non-SADMANS | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| SADMANS | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Drug change: initiate | Non-SADMANS | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SADMANS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dose frequency/schedule change | Non-SADMANS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| SADMANS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Review prescribed medicine | Non-SADMANS | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| SADMANS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Monitoring: laboratory test | Non-SADMANS | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| SADMANS | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Monitoring: non-laboratory test | Non-SADMANS | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| SADMANS | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Drug change | Non-SADMANS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drug change: cease | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Drug change: cease and initiate | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Drug formulation change | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Refer to prescriber | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Other referral required | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Education/counselling session | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Information to nursing staff | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Not classifiable | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Other changes to therapy | SADMANS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Non-clinical | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 49 | 28 | 16 | 30 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truong, M.; Tesfaye, W.; Sud, K.; Van, C.; Seth, S.; Croker, N.; Castelino, R.L. Drug-Related Problems and Sick Day Management Considerations for Medications that Contribute to the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020343

Truong M, Tesfaye W, Sud K, Van C, Seth S, Croker N, Castelino RL. Drug-Related Problems and Sick Day Management Considerations for Medications that Contribute to the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(2):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020343

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruong, Mimi, Wubshet Tesfaye, Kamal Sud, Connie Van, Shrey Seth, Nerida Croker, and Ronald Lynel Castelino. 2024. "Drug-Related Problems and Sick Day Management Considerations for Medications that Contribute to the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 2: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020343

APA StyleTruong, M., Tesfaye, W., Sud, K., Van, C., Seth, S., Croker, N., & Castelino, R. L. (2024). Drug-Related Problems and Sick Day Management Considerations for Medications that Contribute to the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(2), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020343