Radiologic Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Differences in General Characteristics by Gender

3.2. Differences in General Characteristics by Age

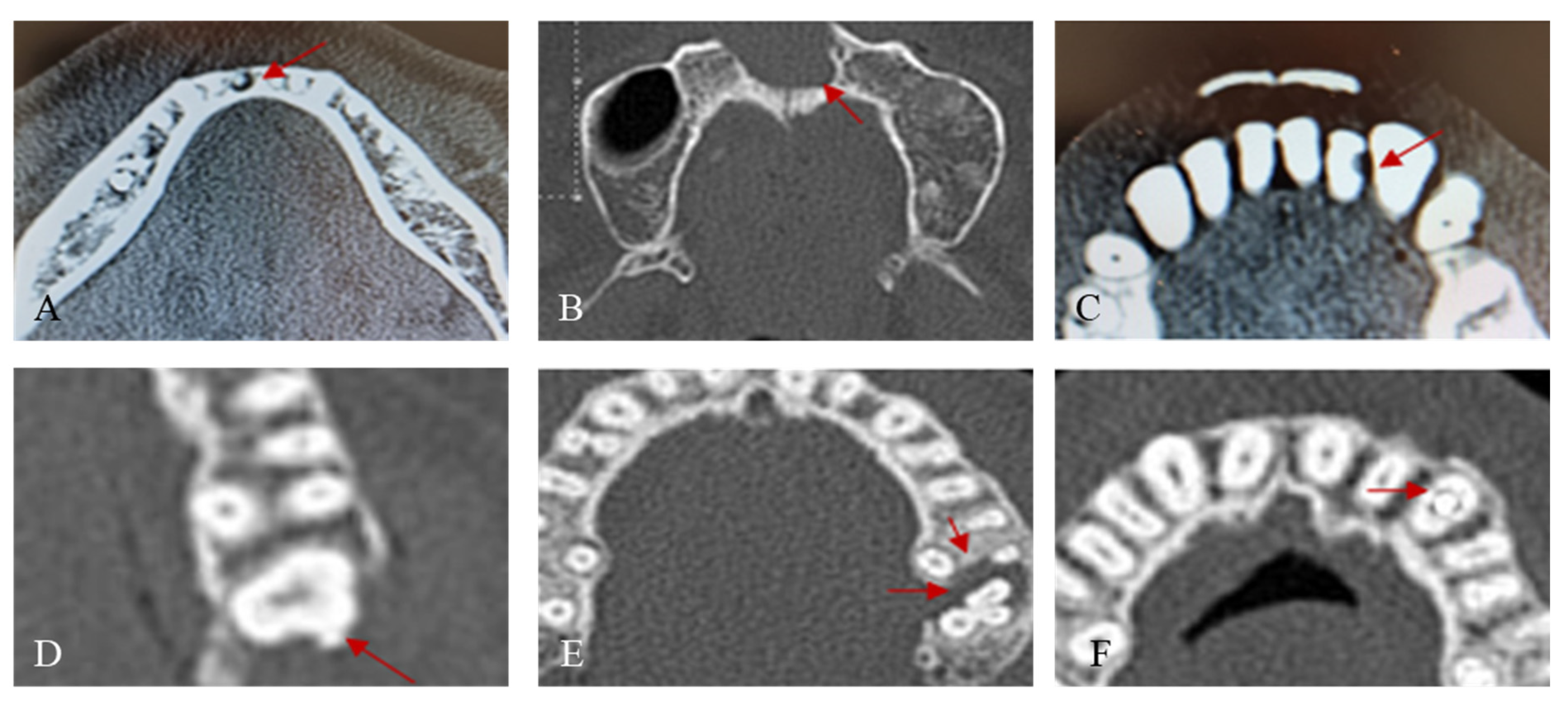

3.3. Evaluation of Oral Condition through the Analysis of Medical Records

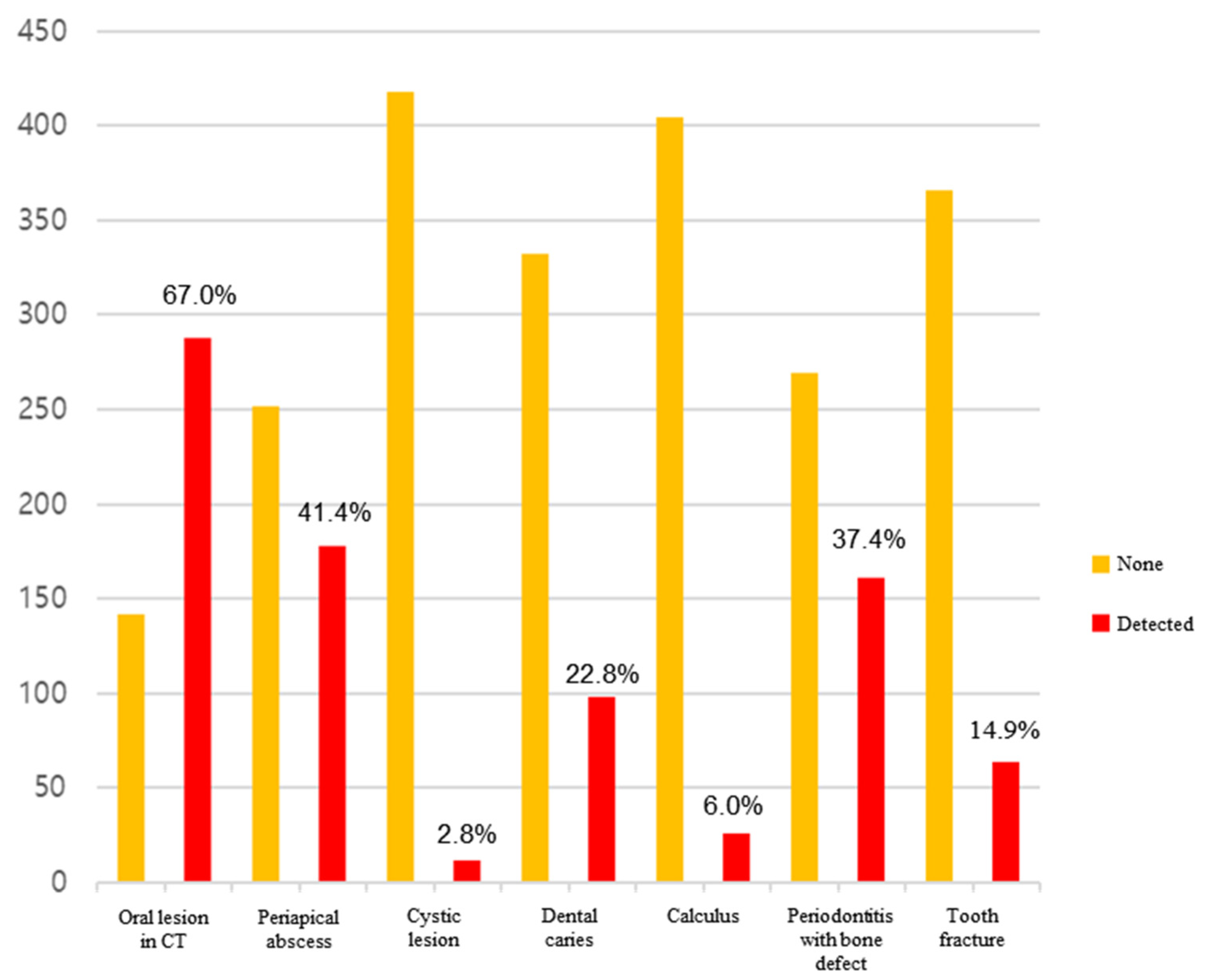

3.3.1. Evaluation of Oral Condition of the Subjects through the Analysis of Medical Records

3.3.2. Differences in Oral Health Status Assessment According to General Characteristics

3.3.3. Risk Factors Influencing the Prevalence of Oral Lesions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blum, D.F.C.; Silva, J.; Baeder, F.M.; Della Bona, Á. The practice of dentistry in intensive care units in brazil. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiv. 2018, 30, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berti-Couto Sde, A.; Couto-Souza, P.H.; Jacobs, R.; Nackaerts, O.; Rubira-Bullen, I.R.; Westphalen, F.H.; Moysés, S.J.; Ignácio, S.A.; Costa, M.B.; Tolazzi, A.L. Clinical diagnosis of hyposalivation in hospitalized patients. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, B.; Fidelis, F.; Mastrocolla, L.; Tempest, L.; Araujo, T.; Castro, F.; Abbud, A.; Kassis, E.; Filho, I. Main aspects of hospital dentistry: Review of its importance. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourrier, F.; Duvivier, B.; Boutigny, H.; Roussel-Delvallez, M.; Chopin, C. Colonization of dental plaque: A source of nosocomial infections in intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 26, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, V.; Hallberg, I.R.; Jahnke, H.; Kleiman, C.; Hagell, P. Oral health, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and intracranial pressure in intubated patients in a neuroscience intensive care unit. Am. J. Crit. Care Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Crit.-Care Nurses 2009, 18, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, D.; Senior, N.; James, I.; Roberts, G. Oral health status of children in a paediatric intensive care unit. Intensiv. Care Med. 2000, 26, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoi, A.P.T.d.; Francesco, A.R.d.; Duarte, A.; Kemp, A.P.T.; Silva-Lovato, C.H. Odontologia hospitalar no brasil: Uma visão geral. Rev. Odontol. UNESP 2009, 38, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.-A.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, K.-S.; Im, H.-M.; Kim, T.-H.; Choi, M.-Y.; Seo, H.-J.; Park, H.-S.; Wang, K.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; et al. Updates of nursing practice guideline for oral care. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2020, 3, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, C.O.F.d.; Belon, L.M.R.; Silva, E.A.d.; Nadai, A.d.; Amaral Filho, M.S.P.d.; Straioto, F.G. The importance of hospital dentistry: Oral health status in hospitalized patients. RGO-Rev. Gaúcha Odontol. 2018, 66, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, J.; Berger, A.M.; Petersen, M.C. Development, testing, and application of the oral assessment guide. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 1988, 15, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jun, M.K.; Ku, J.K.; Kim, I.H.; Park, S.Y.; Hong, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.K. Hospital dentistry for intensive care unit patients: A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özçaka, Ö.; Başoğlu, Ö.; Buduneli, N.; Taşbakan, M.; Bacakoğlu, F.; Kinane, D. Chlorhexidine decreases the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care unit patients: A randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontal Res. 2012, 47, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellissimo-Rodrigues, W.T.; Menegueti, M.G.; Gaspar, G.G.; de Souza, H.C.C.; Auxiliadora-Martins, M.; Basile-Filho, A.; Martinez, R.; Bellissimo-Rodrigues, F. Is it necessary to have a dentist within an intensive care unit team? Report of a randomised clinical trial. Int. Dent. J. 2018, 68, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersel, A.; Babayof, I.; Rosin, A. Oral health needs of elderly short-term patients in a geriatric department of a general hospital. Spec. Care Dent. 2000, 20, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, G.; Love, R.; MacFadyen, E.; Thomson, W. Oral health of older people admitted to hospital for needs assessment. N. Z. Dent. J. 2014, 110, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McNally, L.; Gosney, M.A.; Doherty, U.; Field, E.A. The orodental status of a group of elderly in-patients: A preliminary assessment. Gerodontology 1999, 16, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tablan, O.; Anderson, L.; Besser, R.; Bridges, C.; Hajjeh, R.; CDC; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for preventing health-care–associated pneumonia, 2003: Recommendations of cdc and the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2004, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tada, A.; Miura, H. Prevention of aspiration pneumonia (ap) with oral care. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 55, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjögren, P.; Wårdh, I.; Zimmerman, M.; Almståhl, A.; Wikström, M. Oral care and mortality in older adults with pneumonia in hospitals or nursing homes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Male (n = 288) | Female (n = 142) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission duration | |||

| 1–6 days | 93 (49.2%) | 59 (55.1%) | 0.058 |

| 7–13 days | 33 (17.5%) | 8 (7.5%) | |

| ≥14 days | 63 (33.3%) | 40 (37.4%) | |

| Types of ICU | |||

| Medical | 37 (12.8%) | 33 (23.2%) | 0.009 |

| Surgical | 251 (87.2%) | 109 (76.8%) | |

| Subtypes of ICU | |||

| Cardiac | 13 (4.5%) | 6 (4.2%) | <0.001 |

| Emergency | 79 (27.4%) | 51 (35.9%) | |

| Medical | 23 (8.0%) | 30 (21.1%) | |

| Neurological | 69 (24.0%) | 30 (21.1%) | |

| Surgical | 66 (22.9%) | 18 (12.7%) | |

| Trauma | 38 (13.2%) | 7 (4.9%) | |

| 19–39 Years (n = 92) | 40–59 Years (n = 144) | >60 Years (n = 193) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 71 (77.2%) | 95 (66.0%) | 121 (62.7%) | 0.050 |

| Female | 21 (22.8%) | 49 (34.0%) | 72 (37.3%) | |

| ICU admission duration | ||||

| 1–6 days | 32 (48.5%) | 45 (54.9%) | 74 (50.3%) | 0.432 |

| 7–13 days | 12 (18.2%) | 13 (15.9%) | 16 (10.9%) | |

| ≥14 days | 22 (33.3%) | 24 (29.3%) | 57 (38.8%) | |

| Types of ICU | ||||

| Medical | 6 (6.5%) | 18 (12.5%) | 46 (23.8%) | <0.001 |

| Surgical | 86 (93.5%) | 126 (87.5%) | 147 (76.2%) | |

| Subtypes of ICU | ||||

| Cardiac | 1 (1.1%) | 6 (4.2%) | 12 (6.2%) | <0.001 |

| Emergency | 16 (17.4%) | 43 (29.9%) | 71 (36.8%) | |

| Medical | 4 (4.3%) | 12 (8.3%) | 37 (19.2%) | |

| Neurological | 31 (33.7%) | 32 (22.2%) | 36 (18.7%) | |

| Surgical | 26 (28.3%) | 35 (24.3%) | 22 (11.4%) | |

| Trauma | 14 (15.2%) | 16 (11.1%) | 15 (7.8%) | |

| Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Number of remained teeth | |

| Maxilla | 11.4 ± 4.1 |

| Mandible | 11.8 ± 3.4 |

| Total | 23.2 ± 6.8 |

| Number of missing teeth | |

| Maxilla | 2.6 ± 4.1 |

| Mandible | 2.2 ± 3.4 |

| Total | 4.8 ± 6.8 |

| MT index | 4.80 |

| Numbers of oral lesion per person | 1.5 ± 1.8 |

| Numbers of Patient | Numbers of Missing Teeth | MT Index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 288 | 1330 | 4.62 |

| Female | 142 | 733 | 5.16 |

| ICU admission duration | |||

| 1–6 days | 92 | 78 | 0.85 |

| 7–13 days | 144 | 426 | 2.96 |

| ≥14 days | 193 | 1559 | 8.08 |

| Types of ICU | |||

| Medical | 70 | 504 | 7.20 |

| Surgical | 360 | 1559 | 4.33 |

| Subtypes of ICU | |||

| Cardiac | 19 | 154 | 8.11 |

| Emergency | 130 | 705 | 5.42 |

| Medical | 53 | 381 | 7.19 |

| Neurological | 99 | 346 | 3.49 |

| Surgical | 84 | 264 | 3.14 |

| Trauma | 45 | 211 | 4.69 |

| Male (n = 288) | Female (n = 142) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of remained teeth | |||

| Maxilla | 11.5 ± 4.0 | 11.1 ± 4.2 | 0.313 |

| Mandible | 11.8 ± 3.3 | 11.7 ± 3.4 | 0.733 |

| Total | 23.4 ± 6.7 | 22.8 ± 7.0 | 0.437 |

| Number of missing teeth | |||

| Maxilla | 2.5 ± 4.0 | 2.9 ± 4.2 | 0.313 |

| Mandible | 2.2 ± 3.3 | 2.3 ± 3.4 | 0.733 |

| Total | 4.6 ± 6.7 | 5.2 ± 7.0 | 0.437 |

| Oral lesion in CT images | |||

| None | 82 (28.5%) | 60 (42.3%) | 0.006 |

| Detected | 206 (71.5%) | 82 (57.7%) | |

| Periapical abscess | |||

| None | 158 (54.9%) | 94 (66.2%) | 0.032 |

| Detected | 130 (45.1%) | 48 (33.8%) | |

| Cystic lesion | |||

| None | 281 (97.6%) | 137 (96.5%) | 0.738 |

| Detected | 7 (2.4%) | 5 (3.5%) | |

| Dental caries | |||

| None | 217 (75.3%) | 115 (81.0%) | 0.235 |

| Detected | 71 (24.7%) | 27 (19.0%) | |

| Calculus | |||

| None | 270 (93.8%) | 134 (94.4%) | 0.970 |

| Detected | 18 (6.2%) | 8 (5.6%) | |

| Periodontitis (more than moderate alveolar bone destruction) | |||

| None | 175 (60.8%) | 94 (66.2%) | 0.323 |

| Detected | 113 (39.2%) | 48 (33.8%) | |

| Tooth fracture | |||

| None | 237 (82.3%) | 129 (90.8%) | 0.028 |

| Detected | 51 (17.7%) | 13 (9.2%) | |

| Numbers of oral lesion | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.116 |

| 19–39 Years (n = 92) | 40–59 Years (n = 144) | ≥60 Years (n = 193) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of remained teeth | ||||

| Maxilla | 13.7 ± 1.0 | 12.5 ± 2.9 | 9.5 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Mandible | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 12.5 ± 2.2 | 10.4 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Total | 27.2 ± 1.7 | 25.0 ± 4.6 | 19.9 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Number of missing teeth | ||||

| Maxilla | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 2.9 | 4.5 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Mandible | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 2.2 | 3.6 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Total | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 4.6 | 8.1 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Oral lesion in CT images | ||||

| None | 48 (52.2%) | 39 (27.1%) | 55 (28.5%) | <0.001 |

| Detected | 44 (47.8%) | 105 (72.9%) | 138 (71.5%) | |

| Periapical abscess | ||||

| None | 66 (71.7%) | 81 (56.2%) | 105 (54.4%) | 0.016 |

| Detected | 26 (28.3%) | 63 (43.8%) | 88 (45.6%) | |

| Cystic lesion | ||||

| None | 90 (97.8%) | 139 (96.5%) | 188 (97.4%) | 0.817 |

| Detected | 2 (2.2%) | 5 (3.5%) | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Dental caries | ||||

| None | 79 (85.9%) | 108 (75.0%) | 145 (75.1%) | 0.090 |

| Detected | 13 (14.1%) | 36 (25.0%) | 48 (24.9%) | |

| Calculus | ||||

| None | 86 (93.5%) | 136 (94.4%) | 182 (94.3%) | 0.948 |

| Detected | 6 (6.5%) | 8 (5.6%) | 11 (5.7%) | |

| Periodontitis (more than moderate alveolar bone destruction) | ||||

| None | 72 (78.3%) | 87 (60.4%) | 110 (57.0%) | 0.002 |

| Detected | 20 (21.7%) | 57 (39.6%) | 83 (43.0%) | |

| Tooth fracture | ||||

| None | 77 (83.7%) | 122 (84.7%) | 167 (86.5%) | 0.795 |

| Detected | 15 (16.3%) | 22 (15.3%) | 26 (13.5%) | |

| Numbers of oral lesion | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

| Medical (n = 70) | Surgical (n = 360) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of remained teeth | |||

| Maxilla | 10.0 ± 5.1 | 11.7 ± 3.8 | 0.009 |

| Mandible | 10.8 ± 4.1 | 12.0 ± 3.2 | 0.027 |

| Total | 20.8 ± 8.5 | 23.7 ± 6.4 | 0.008 |

| Number of missing teeth | |||

| Maxilla | 4.0 ± 5.1 | 2.3 ± 3.8 | 0.009 |

| Mandible | 3.2 ± 4.1 | 2.0 ± 3.2 | 0.027 |

| Total | 7.2 ± 8.5 | 4.3 ± 6.4 | 0.008 |

| Oral lesion in CT images | |||

| None | 28 (40.0%) | 114 (31.7%) | 0.223 |

| Detected | 42 (60.0%) | 246 (68.3%) | |

| Periapical abscess | |||

| None | 44 (62.9%) | 208 (57.8%) | 0.511 |

| Detected | 26 (37.1%) | 152 (42.2%) | |

| Cystic lesion | |||

| None | 69 (98.6%) | 349 (96.9%) | 0.719 |

| Detected | 1 (1.4%) | 11 (3.1%) | |

| Dental caries | |||

| None | 52 (74.3%) | 280 (77.8%) | 0.630 |

| Detected | 18 (25.7%) | 80 (22.2%) | |

| Calculus | |||

| None | 67 (95.7%) | 337 (93.6%) | 0.688 |

| Detected | 3 (4.3%) | 23 (6.4%) | |

| Periodontitis (more than moderate alveolar bone destruction) | |||

| None | 46 (65.7%) | 223 (61.9%) | 0.645 |

| Detected | 24 (34.3%) | 137 (38.1%) | |

| Tooth fracture | |||

| None | 65 (92.9%) | 301 (83.6%) | 0.071 |

| Detected | 5 (7.1%) | 59 (16.4%) | |

| Numbers of oral lesion | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 0.112 |

| Variables (ref.: None) | B | SE | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.753 | 0.229 | 0.471 | (0.300~0.738) | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.030 | 0.007 | 1.030 | (1.016~1.044) | 0.000 |

| Types of ICU | 0.513 | 0.295 | 1.671 | (0.938~2.976) | 0.081 |

| ICU admission day | −0.009 | 0.004 | 0.991 | (0.983~0.998) | 0.013 |

| Numbers of remained teeth | 0.012 | 0.019 | 1.012 | (0.975~1.052) | 0.522 |

| -2LL = 504.550, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.126, Hosmer and Lemeshow x2 = 7.198 (p = 0.515) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y. Radiologic Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133913

Kim Y. Radiologic Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133913

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yesel. 2024. "Radiologic Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133913

APA StyleKim, Y. (2024). Radiologic Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3913. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133913