Complicated Form of Medication Overuse Headache Is Severe Version of Chronic Migraine

Abstract

1. Introduction

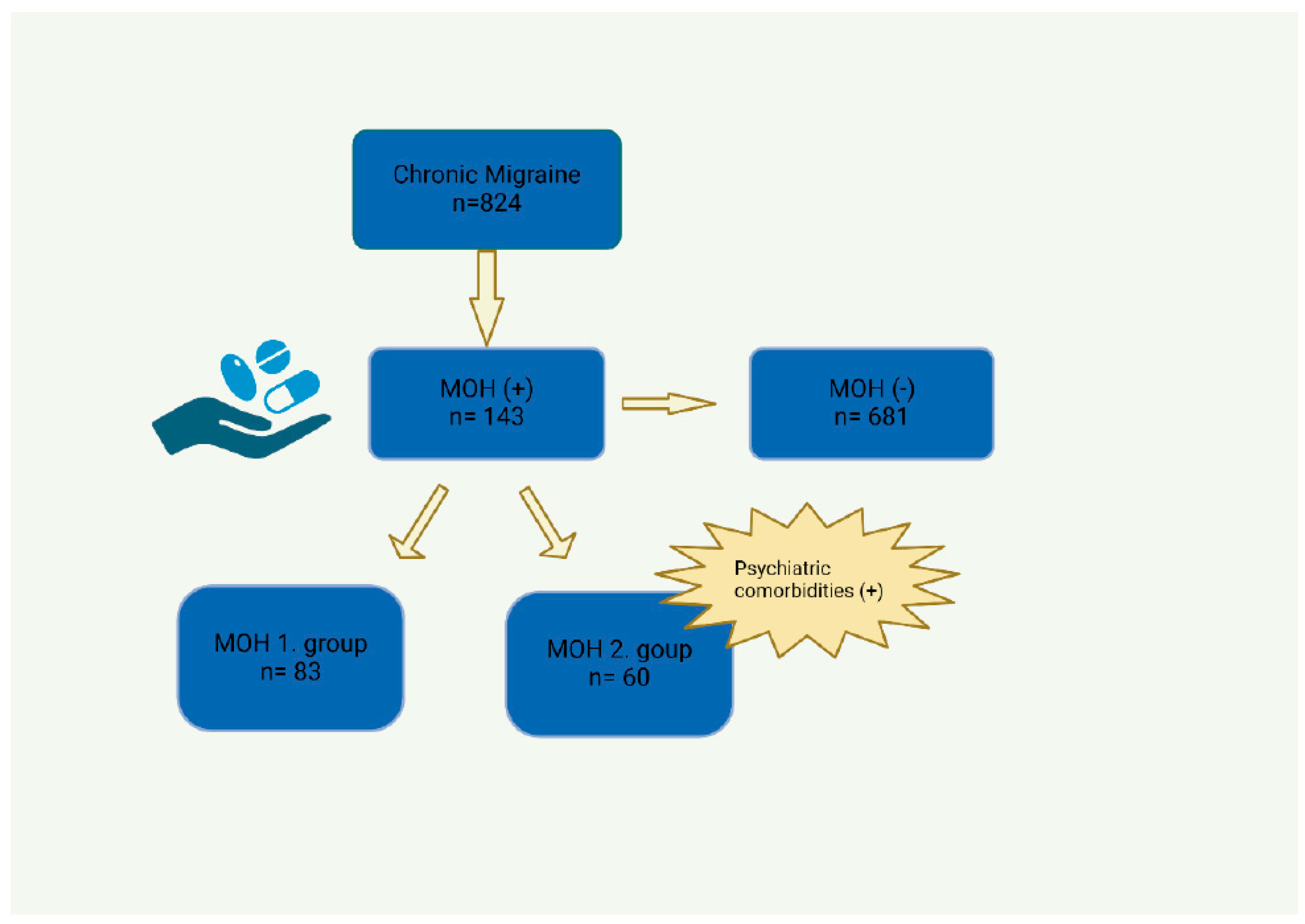

2. Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Key Messages

- A medication overuse headache (MOH) is a frequent complication of chronic migraine (CMs) influenced by similar triggers and symptoms.

- Complicated MOHs are associated with significant psychiatric comorbidities, highlighting the need for holistic treatment approaches.

- A family history of migraines increases the likelihood of developing an MOH.

- Characteristics such as high frequency, severe pain, and bilateral localization are closely linked to MOH development.

- MOH patients often experience more intense migraine symptoms, such as nausea and photophobia.

- Prophylactic treatments are more commonly used among MOH patients, indicating challenging management needs.

- Early detection of MOH can lead to better management and potentially prevent its progression.

- Comorbid conditions like sleep disturbances and emotional stress are prevalent in MOH patients and must be addressed in treatment.

- Managing an MOH requires a multidisciplinary approach due to its complexity and the variety of symptoms and comorbidities involved.

- The study’s findings stress the importance of further research to better understand MOHs and improve treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Natoli, J.L.; Manack, A.; Dean, B.; Butler, Q.; Turkel, C.C.; Stovner, L.; Lipton, R.B. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia 2009, 30, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buse, D.C.; Manack, A.N.; Fanning, K.M.; Serrano, D.; Reed, M.L.; Turkel, C.C.; Lipton, R.B. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: Results from the American migraine prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache 2012, 52, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.T.; Ornello, R.; Quatrosi, G.; Torrente, A.; Albanese, M.; Vigneri, S.; Guglielmetti, M.; De Marco, C.M.; Dutordoir, C.; Colangeli, E.; et al. Medication overuse and drug addiction: A narrative review from addiction perspective. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffersen, E.S.; Lundqvist, C. Medication-overuse headache: A review. J. Pain Res. 2014, 7, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, A.; Martelletti, P. Chronic migraine plus medication overuse headache: Two entities or not? J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehlsteibl, D.; Schankin, C.; Hering, P.; Sostak, P.; Straube, A. Anxiety disorders in headache patients in a specialised clinic: Prevalence and symptoms in comparison to patients in a general neurological clinic. J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’amico, D.; Grazzi, L.; Guastofierro, E.; Sansone, E.; Leonardi, M.; Raggi, A. Withdrawal failure in patients with chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2021, 144, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niddam, D.M.; Lai, K.-L.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.R.; Chen, W.T.; Fuh, J.L.; Wang, S.J. Brain metabolites in chronic migraine patients with medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamberardino, M.A.; Martelletti, P. Comorbitidies in Headache Disorders; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bigal, M.E.; Rapoport, A.M.; Sheftell, F.D.; Tepper, S.J.; Lipton, R.B. Transformed migraine and medication overuse in a tertiary headache centre—Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Cephalalgia 2004, 24, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, N.T.; Stubits, E.; Nigam, M.R. Transformation of migraine into daily headache: Analysis of factors. Headache 1982, 22, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, D.J.; Swanson, J.W.; Dodick, D.W. Medication induced (analgesic rebound) headache: Historical aspects and initial descriptions of the North American experience. Headache 2001, 41, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jumah, M.; Al Khathaami, A.M.; Kojan, S.; Hussain, M.; Thomas, H.; Steiner, T.J. The prevalence of primary headache disorders in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional population-based study. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoni, V.; Mascarella, D.; Giannini, G.; Bauleo, S.; Torelli, P.; Pierangeli, G.; Cortelli, P.; Cevoli, S. Prevalence, natural history and dynamic nature of chronic headache and medication overuse headache in Italy: The SPARTACUS study. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 03331024231157677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micele, V.; Sara, B.; Grazia, S.; Allena, M.; Guaschino, E.; Nappi, G.; Tassorelli, C. Factors associated to chronic migraine with medication overuse: A cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 2045–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, E.; Pedraza, M.I.; Munoz, I.; Mulero, P.; Ruiz, M.; de la Cruz, C.; Barón, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Herrero, S.; Guerrero, A.L. Chronic migraine with and without medication overuse: Experience in a hospital series of 434 patients. Neurología 2015, 30, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guendler, V.Z.; Mercante, J.P.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Zukerman, E.; Peres, M.F. Factors associated with acute medication overuse in chronic migraine patients. Einstein 2012, 10, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saper, J.R.; Lake, A.E., 3rd. Medication overuse headache: Type I and type II. Cephalalgia 2006, 26, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, A.E., 3rd. Medication overuse headache: Biobehavioral issues and solutions. Headache 2006, 46 (Suppl. S3), S88–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radat, F.; Creac’h, C.; Swendsen, J.D.; Lafittau, M.; Irachabal, S.; Dousset, V.; Henry, P. Psychiatric comorbidity in the evolution from migraine to medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia 2005, 25, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louter, M.A.; Bosker, J.E.; Van Oosterhout, W.P.; Van Zwet, E.W.; Zitman, F.G.; Ferrari, M.D.; Terwindt, G.M. Cutaneous allodynia as a predictor of migraine chronification. Brain 2013, 136, 3489–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.A.; Jan, A. Medication-Overuse Headache; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, I.D.; Dodick, D.; Ossipov, M.H.; Porreca, F. Pathophysiology of medication overuse headache: Insights and hypotheses from preclinical studies. Cephalalgia 2011, 31, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposio, E.; Raposio, G.; Del Duchetto, D.; Tagliatti, E.; Cortese, K. Morphologic vascular anomalies detected during migraine surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 75, 4069–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, H.C.; Donoghue, S.; Gaul, C.; Holle-Lee, D.; Jöckel, K.H.; Mian, A.; Schröder, B.; Kühl, T. Prevention of medication overuse and medication overuse headache in patients with migraine: A randomized, controlled, parallel, allocation-blinded, multicenter, prospective trial using a mobile software application. Trials 2022, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CM with MOH | CM without MOH | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 41.46 (11.81) | 41.98 (15.5) | 0.656 |

| -Female -Male | 122 (85.3) 21 (14.7) | 564 (82.8) 117 (17.2) | 0.468 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 21 (14.7) | 110 (16.2) | 0.663 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 0 (0) | 14 (2.1) | 0.146 |

| Family history of migraine, n (%) | 64 (44.8) | 202 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 22 (15.4) | 59 (8.7) | 0.014 |

| Frequency of attacks, day/months, mean (SD) | 20.18 (8.66) | 15.56 (9.62) | <0.001 |

| VAS, (mean, SD) | 8.52 (1.46) | 7.87 (2.09) | 0.010 |

| Pain Localization, n (%) -Unilateral -Bilateral -Unilateral + Bilateral | 40 (60) 10 (10.2) 16 (24.2) | 156 (76. 8) 16 (7.9) 31 (15.3) | 0.033 |

| Migraine duration, month Mean (SD) | 194. 48 (134.26) | 159. 59 (137.16) | 0.007 |

| Pain acompanying symptoms | |||

| Nausea, n (%) | 84 (58.7) | 309 (45.4) | 0.004 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 54 (37.8) | 182 (26.7) | 0.008 |

| Photophobia, n (%) | 81 (56.6) | 295 (43.3) | 0.004 |

| Phonophobia, n (%) | 87 (60.8) | 305 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Osmophobia, n (%) | 75 (52.4) | 246 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Allodynia, n (%) | 32 (22.4) | 102 (15) | 0.029 |

| Autonomic Symtoms, n (%) | 13 (9.1) | 29 (4.3) | 0.017 |

| Prophylaxis, n (%) | 113 (79.0) | 453 (66.5) | 0.003 |

| MOH+ | MOH− | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atopy, n (%) | 34 (23.8) | 106 (15.6) | 0.017 |

| Allergies, n (%) | 6 (4.2) | 37 (5.4) | 0.545 |

| Sleep disturbances, n (%) | 50 (35.0) | 168 (24.7) | 0.011 |

| Emotional stress, n (%) | 40 (28) | 132 (19.4) | 0.022 |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 18 (12.6) | 117 (17.2) | 0.177 |

| Depression, n (%) | 10 (7.0) | 44 (6.5) | 0.815 |

| Bruxizm, n (%) | 9 (6.3) | 45 (6.6) | 0.890 |

| Fibromyalgia, n (%) | 29 (20.3) | 130 (19.1) | 0.743 |

| OR | 95% C.I. for OR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| VAS | 1.44 | 1.01 | 2.05 | 0.046 |

| Frequency of attacks | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 0.010 |

| Pain Localization (bilateral) | 5.92 | 1.46 | 24.04 | 0.013 |

| Phonophobia | 55.70 | 4.65 | 667.10 | 0.002 |

| Photophobia | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.033 |

| Allodynia | 2.68 | 1.04 | 6.91 | 0.041 |

| Fibromyalgia | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.035 |

| MOH Grup-1 | MOH Grup-2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 40.49 (10.3) | 42. 77 (13.57) | 0.260 |

| Female -Male | 70 (84.3) 13 (15.7) | 52 (86.7) 8 (13.3) | 0.813 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 12 (14.5) | 9 (15.0) | 0.928 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 83 (100) | 60 (100) | 0.00 |

| Family history of migraine, n (%) | 31 (37.3) | 33 (55.0) | 0.036 |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 9 (10.8) | 13 (21.7) | 0.770 |

| Frequency of attacks, day/months, mean (SD) | 18.56 (8.66) | 21.3 (8.56) | 0.129 |

| VAS, mean (SD) | 8.52 (1.88) | 8.52 (1.09) | 0.356 |

| Pain Localization, n (%) -Unilateral -Bilateral -Unilateral + Bilateral | 22 (78.6) 1 (3.6) 5 (17.9) | 18 (47.4) 9 (23.7) 11 (28.9) | 0.021 |

| Migraine duration, month Mean, SD | 210.98 (136.4) | 181.81 (132.53) | 0.255 |

| Pain acompanying symptoms | |||

| Nausea, n (%) | 36 (43.4) | 48 (80.0) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 25 (30.1) | 29 (48.3) | 0.027 |

| Photophobia, n (%) | 35 (42.2) | 46 (76.7) | <0.001 |

| Phonophobia, n (%) | 41 (49.4) | 46 (76.7) | 0.001 |

| Osmophobia, n (%) | 34 (41.0) | 41 (68.3) | 0.001 |

| Allodynia, n (%) | 14 (16.9) | 18 (30.0) | 0.063 |

| Autonomic Symtoms, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 9 (15.0) | 0.044 |

| Prophylaxis, n (%) | 66 (79.5) | 47 (78.3) | 0.864 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Göçmez Yılmaz, G.; Ghouri, R.; Özdemir, A.A.; Özge, A. Complicated Form of Medication Overuse Headache Is Severe Version of Chronic Migraine. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133696

Göçmez Yılmaz G, Ghouri R, Özdemir AA, Özge A. Complicated Form of Medication Overuse Headache Is Severe Version of Chronic Migraine. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133696

Chicago/Turabian StyleGöçmez Yılmaz, Gülcan, Reza Ghouri, Asena Ayça Özdemir, and Aynur Özge. 2024. "Complicated Form of Medication Overuse Headache Is Severe Version of Chronic Migraine" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133696

APA StyleGöçmez Yılmaz, G., Ghouri, R., Özdemir, A. A., & Özge, A. (2024). Complicated Form of Medication Overuse Headache Is Severe Version of Chronic Migraine. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133696