Pulmonary Function Tests: Easy Interpretation in Three Steps

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Before Starting

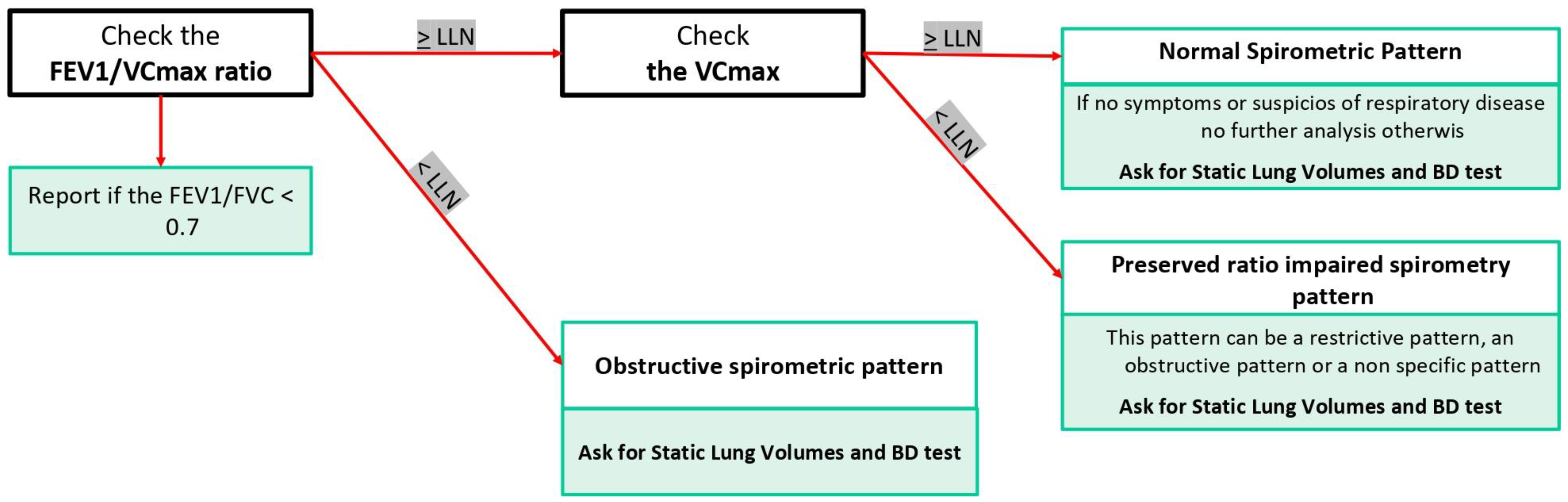

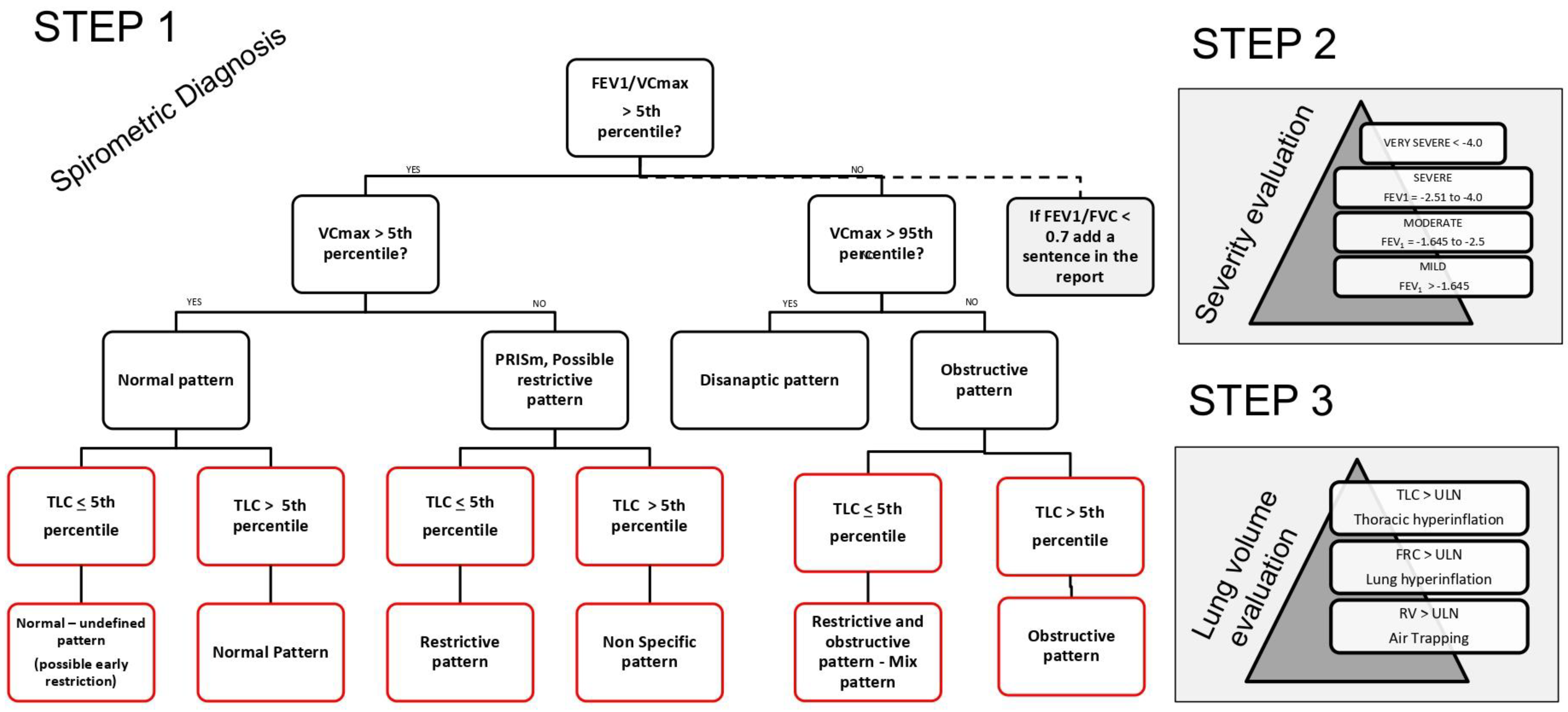

1.2. First Step: Interpreting Spirometry Results

1.2.1. Forced Spirometry: Flow Volume Curve

1.2.2. Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm)

1.2.3. Dysanaptic Pattern

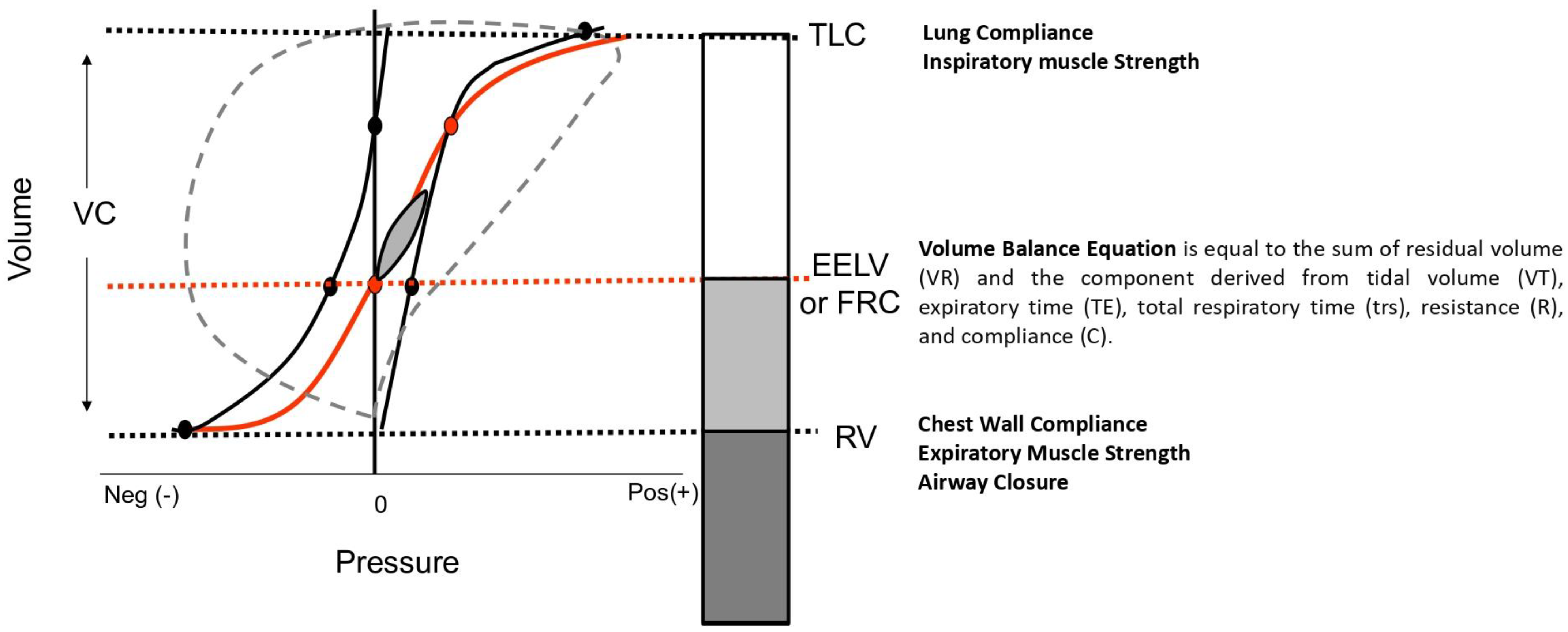

1.2.4. Interpreting Static Lung Volume Measurements

1.3. Step 2 and Step 3

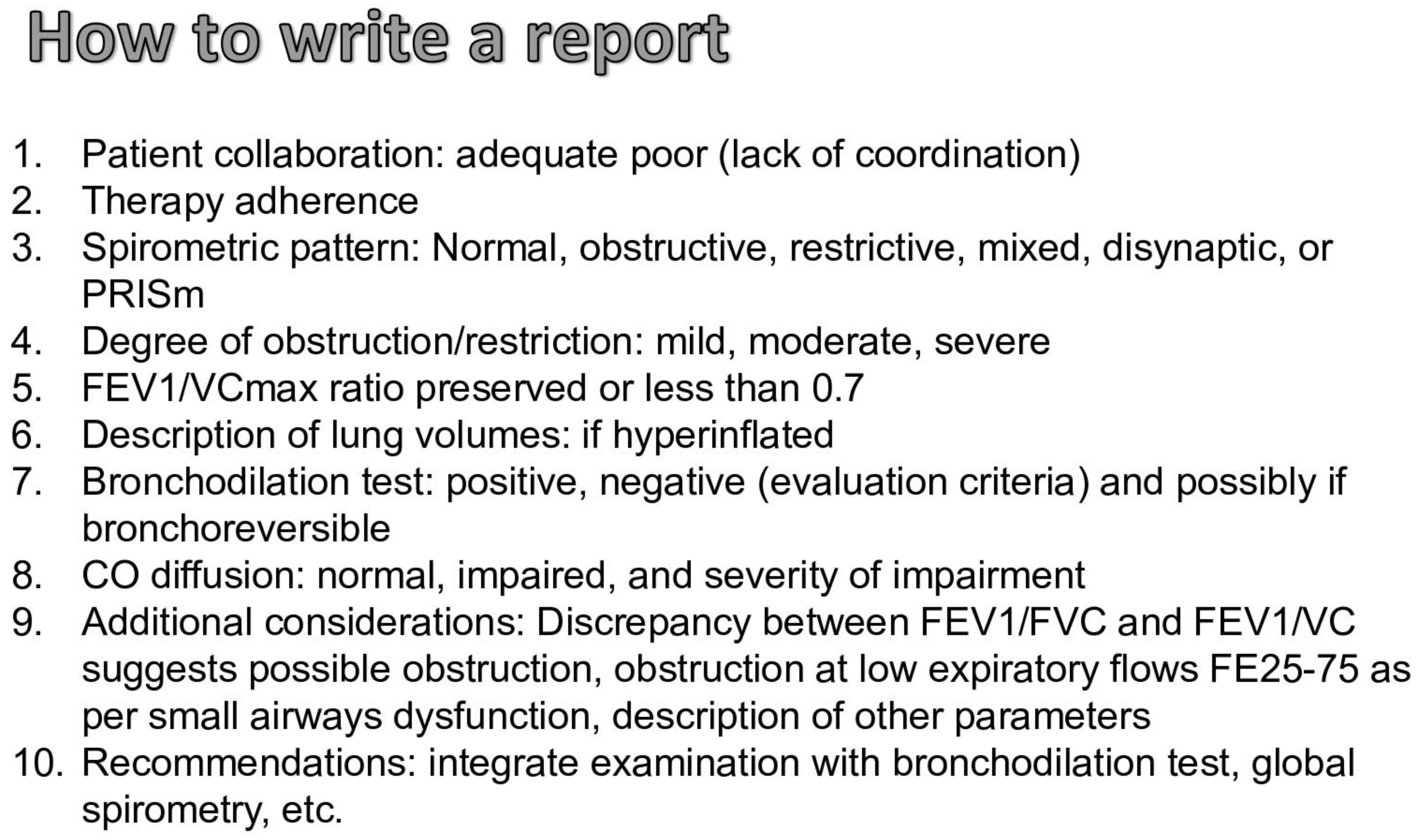

1.4. How to Write the Report of the Spirometry and Clinical Cases

- Case 1 (Figure 5)

- Premise: Adequate coordination; the subject did not assume inhalatory therapy.

- FEV1/VC max is greater than the LLN (Z-score: 0.89) and the VC max is within the normal range (Z-score: 0.06), indicating normal spirometry.

- Static lung volumes (plethysmography) (Figure 2): The TLC is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −2.55), suggesting a “Normal—undefined pattern (possible early restriction)”.

- Step 2: Since the spirometry is normal, there is no classification of severity. However, if considered as a restrictive pattern, it would indicate mild restriction due to FEV1 being greater than the LLN (Z-score: 0.06).

- Step 3: Lung Volume Evaluation

- No lung or thoracic hyperinflation, no air trapping.

- Other Tests:

- Bronchodilation test not available.

- DLco and DLco/VA are within the normal range, with a reduction in VA.

- Observations: resistance is within the normal range.

- Conclusions: Normal—undefined pattern. If clinically compatible, this could indicate possible early restriction.

- Comments on this Spirometry: This is a challenging case of normal spirometry with impaired static lung volumes. According to spirometric guidelines, clinicians might have stopped the evaluation and reported this as normal based solely on slow/forced spirometry. However, if the patient undergoes static lung volume evaluation, the diagnosis should be revised to a restrictive ventilatory defect, contradicting the initial spirometry results [43]. According to recommendations, this case should be scored as mild based on the TLC, and normal based on the FVC. Therefore, it may be beneficial to standardize the diagnosis and severity criteria to ensure consistency.

- 2.

- Case 2 (Figure 5)

- Premise: Adequate coordination; the subject did not assume inhalatory therapy.

- FEV1/VC max is greater than the LLN (Z-score: 0.72) and VC max is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −2.36), indicating a PRISm pattern.

- Static lung volumes (plethysmography) (Figure 2): The TLC is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −2.37), suggesting a “restrictive pattern.”

- Step 2: According to the evaluation of FEV1 (Z-score: −1.84), the severity of the restriction is moderate.

- Step 3: Lung Volume Evaluation

- No lung or thoracic hyperinflation, no air trapping.

- Other Tests:

- Bronchodilation test not available.

- DLco is reduced, but DLco/VA is within the normal range, due to a reduction in VA.

- Observations: Resistance is within the normal range. Despite a decrease in FRC and TLC, the RV is normal.

- Conclusions: Moderate restrictive pattern with a severe decrease in the diffusion of CO, but a preserved DLco/VA. A reduction in DLco due to a decrease in alveolar volume is noted, but not in DLco/VA. Additionally, the residual volume is within normal limits, indicating air trapping in the context of a restrictive pattern.

- Comments on this Spirometry: This is a classic case of a restrictive pattern. The differences between the UFC and the guidelines are as follows: the severity is evaluated according to FEV1; the score is different, as the UFC considers alterations between −1.645 and −2.5 as moderate, whereas spirometric recommendations classify this as mild. Additionally, because the RV/TLC ratio is increased, it should be reported as a complex restriction, but in the UFC, this is noted as a supplementary comment. According to Figure 1, if only the slow/forced maneuver had been performed, the report would have been: Pattern PRISm, possible restriction, with a recommendation to evaluate static lung volumes and perform a bronchodilation test.

- 3.

- Case 3 (Figure 5)

- FEV1/VC max is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −1.71) and VC max is within the normal range (Z-score: −0.10), indicating an obstructive pattern.

- Static lung volumes (plethysmography) (Figure 2): The TLC is greater than the LLN (Z-score: 0.41), confirming an “obstructive pattern.”

- Step 2: According to the evaluation of FEV1 (Z-score: −1.16), the severity of the obstruction is mild.

- Step 3: Lung Volume Evaluation

- TLC is within the normal range, the FRC is increased (Z-score: 2.15), and the RV is close to the ULN.

- Other Tests:

- Bronchodilation test and DLco not available.

- Observations: Resistance is increased.

- Conclusions: Mild obstructive pattern with lung hyperinflation. Additionally, the residual volume is close to the ULN, indicating a possible air trapping, and plethysmographic lung resistance is increased.

- Comments on this Spirometry: This is a classic case of a mild obstructive pattern. The differences between the UFC and the guidelines are as follows: according to the recommendations, the severity of this case cannot be scored. This pattern could be easily interpreted as a dysanaptic pattern because the FEV1 and FVC are normal. To avoid this misinterpretation, we have arbitrarily defined the dysanaptic pattern as an obstructive pattern with an FVC greater than the ULN.

- 4.

- Case 4 (Figure 5)

- FEV1/VC max is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −2.41) and VC max is lower than the normal range (Z-score: −2.93), indicating an obstructive pattern.

- Static lung volumes (plethysmography) (Figure 2): The TLC is lower than the LLN (Z-score: −4.34), suggesting a “mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern.”

- Step 2: According to the evaluation of FEV1 (Z-score: −2.91), the severity of the mixed pattern is severe.

- Step 3: Lung Volume Evaluation

- TLC, FRC, and RV are lower than the ULN.

- Other Tests:

- Bronchodilation test and DLco not available.

- Observations: Resistance is within the normal range.

- Conclusions: Severe mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern.

- Comments on this Spirometry: This is a complex case of a mixed pattern. According to the guidelines, it should be reported as simply restrictive because the FEV1/FVC ratio is within the normal range, although close to the LLN. However, in this case, the FEV1/VC max is lower than the LLN, and the difference between VC and FVC is significant. Moreover, if only the forced spirometry was performed, this case would be reported as a PRISm pattern, but with the slow maneuver, it is identified as an obstructive pattern. This is a complex but illustrative case of how the two flowcharts differ.

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| %pr | Percentage of Predicted |

| ATS | American Thoracic Society |

| BD | Bronchodilator |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test |

| DLCO | Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide |

| ERS | European Respiratory Society |

| FEF25-75 | Forced Expiratory Flow between 25% and 75% of lung volume |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in one second |

| FOT | Forced Oscillometry Technique |

| FRC | Functional Residual Capacity |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| GLI | Global Lung Function Initiative |

| GOLD | Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| LLN | Lower Limit of Normal |

| PFTs | Pulmonary Function Tests |

| PRISm | Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry |

| RV | Residual Volume |

| SVC | Slow Vital Capacity |

| TLC | Total Lung Capacity |

| UFC | Unified Flow Chart |

| ULN | Upper Limit of Normal |

| VC | Vital Capacity |

References

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, R.; Viegi, G.; Brusasco, V.; Crapo, R.O.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; van der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; Hankinson, J.; et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; van der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, S.; Sherrill, D.L.; Venker, C.; Ceccato, C.M.; Halonen, M.; Martinez, F.D. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: A longitudinal study. Thorax 2010, 65, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, R.E.; Cowl, C.T.; Bjoraker, J.A.; Scanlon, P.D. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest 2009, 135, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle Rubio, M.; Rodríguez Hermosa, J.L.; Miravitlles, M.; López-Campos, J.L. Determinants in the Underdiagnosis of COPD in Spain-CONOCEPOC Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneroni, C.; Valach, C.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Gobbi, A.; Dellacà, R.L.; Breyer, M.-K.; Hartl, S.; Sunanta, O.; Irvin, C.G.; Schiffers, C.; et al. Diagnostic Potential of Oscillometry: A Population-based Approach. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí, A.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Halpin, D.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.; Bourbeau, J.; Han, M.K.; Martinez, F.J.; Montes De Oca, M.; et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Tammeling, G.J.; Cotes, J.E.; Pedersen, O.F.; Peslin, R.; Yernault, J.C. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 1993, 16, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanojevic, S.; Graham, B.L.; Cooper, B.G.; Thompson, B.R.; Carter, K.W.; Francis, R.W.; Hall, G.L.; Global Lung Function Initiative TLCO Working Group; Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) TLCO. Official ERS technical standards: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for the carbon monoxide transfer factor for Caucasians. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, G.L.; Filipow, N.; Ruppel, G.; Okitika, T.; Thompson, B.; Kirkby, J.; Steenbruggen, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Stanojevic, S. Official ERS technical standard: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for static lung volumes in individuals of European ancestry. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2000289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.M.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brems, J.H.; Balasubramanian, A.; Raju, S.; Putcha, N.; Fawzy, A.; Hansel, N.N.; Wise, R.A.; McCormack, M.C. Changes in Spirometry Interpretative Strategies: Implications for Classifying COPD and Predicting Exacerbations. Chest 2024, S0012-3692(24)00423-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, J.-K.; Hwang, Y.-I.; Seo, H.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, S.-R.; Kim, H.J.; Jung, K.-S.; Yoo, K.H.; Kim, D.K. Spirometric Interpretation and Clinical Relevance According to Different Reference Equations. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llordés, M.; Jaen, A.; Zurdo, E.; Roca, M.; Vazquez, I.; Almagro, P.; EGARPOC collaboration group. Fixed Ratio versus Lower Limit of Normality for Diagnosing COPD in Primary Care: Long-Term Follow-Up of EGARPOC Study. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative for Asthma GINA. 2023. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Graham, B.L.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Cooper, B.G.; Jensen, R.; Kendrick, A.; MacIntyre, N.R.; Thompson, B.R.; Wanger, J. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neder, J.A.; Berton, D.C.; O’Donnell, D.E. The Lung Function Laboratory to Assist Clinical Decision-Making in Pulmonology. Chest 2020, 158, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santus, P.; Radovanovic, D.; Pecchiari, M.; Ferrando, M.; Tursi, F.; Patella, V.; Braido, F. The Relevance of Targeting Treatment to Small Airways in Asthma and COPD. Respir. Care 2020, 65, 1392–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, S.D.; Dales, R.E.; Cardinal, P. How accurate is spirometry at predicting restrictive pulmonary impairment? Chest 1999, 115, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Pierre, M.; Ladha, J.; Berton, D.C.; Reimao, G.; Castelli, G.; Marillier, M.; Bernard, A.-C.; O’Donnell, D.E.; Neder, J.A. Is the Slow Vital Capacity Clinically Useful to Uncover Airflow Limitation in Subjects with Preserved FEV1/FVC Ratio? Chest 2019, 156, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusasco, V.; Pellegrino, R.; Rodarte, J.R. Vital capacities in acute and chronic airway obstruction: Dependence on flow and volume histories. Eur. Respir. J. 1997, 10, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torén, K.; Olin, A.-C.; Lindberg, A.; Vikgren, J.; Schiöler, L.; Brandberg, J.; Johnsson, Å.; Engström, G.; Persson, H.L.; Sköld, M.; et al. Vital capacity and COPD: The Swedish CArdioPulmonary bioImage Study (SCAPIS). Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2016, 11, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.D.; Irvin, C.G. The detection of collapsible airways contributing to airflow limitation. Chest 1995, 107, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, S.K. Forced vital capacity, slow vital capacity, or inspiratory vital capacity: Which is the best measure of vital capacity? J. Asthma 1998, 35, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinke, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Hazeki, N.; Kotani, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Nishimura, Y. Visualized changes in respiratory resistance and reactance along a time axis in smokers: A cross-sectional study. Respir. Investig. 2013, 51, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yernault, J. The birth and development of the forced expiratory manoeuvre: A tribute to Robert Tiffeneau (1910–1961). Eur. Respir. J. 1997, 10, 2704–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, J.J.; Castellano, M.V.C.d.O.; Vianna, F.d.A.F.; Nacif, S.R.; Rodrigues Junior, R.; Rodrigues, S.C.S. Clinical and functional correlations of the difference between slow vital capacity and FVC. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2020, 46, e20180328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Halbert, R.J. Point: Should we abandon FEV1/FVC <0.70 to detect airway obstruction? No. Chest 2010, 138, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, P.; Brusasco, V. Counterpoint: Should we abandon FEV1/FVC < 0.70 to detect airway obstruction? Yes. Chest 2010, 138, 1040–1042; discussion 1042–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Cooper, B.G.; Stanojevic, S. Letter to the Editor, International Journal of COPD [Letter]. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2020, 15, 2307–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güder, G.; Brenner, S.; Angermann, C.E.; Ertl, G.; Held, M.; Sachs, A.P.; Lammers, J.-W.; Zanen, P.; Hoes, A.W.; Störk, S.; et al. GOLD or lower limit of normal definition? A comparison with expert-based diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a prospective cohort-study. Respir. Res. 2012, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerveri, I.; Corsico, A.G.; Accordini, S.; Niniano, R.; Ansaldo, E.; Antó, J.M.; Künzli, N.; Janson, C.; Sunyer, J.; Jarvis, D.; et al. Underestimation of airflow obstruction among young adults using FEV1/FVC <70% as a fixed cut-off: A longitudinal evaluation of clinical and functional outcomes. Thorax 2008, 63, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.; Arnold, N.; Skinner, B.; Simmering, J.; Eberlein, M.; Comellas, A.P.; Fortis, S. Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry in a Spirometry Database. Respir. Care 2021, 66, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.S.; Hokanson, J.E.; Regan, E.A.; Young, K.A.; Make, B.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; Mason, S.E.; San Jose Estepar, R.; Crapo, J.D.; Silverman, E.K. Significant Spirometric Transitions and Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry among Ever Smokers. Chest 2022, 161, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doña, E.; Reinoso-Arija, R.; Carrasco-Hernandez, L.; Doménech, A.; Dorado, A.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Exploring Current Concepts and Challenges in the Identification and Management of Early-Stage COPD. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, E.S.; Castaldi, P.J.; Cho, M.H.; Hokanson, J.E.; Regan, E.A.; Make, B.J.; Beaty, T.H.; Han, M.K.; Curtis, J.L.; Curran-Everett, D.; et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magner, K.M.A.; Cherian, M.; Whitmore, G.A.; Vandemheen, K.L.; Bergeron, C.; Cote, A.; Field, S.K.; Lemière, C.; McIvor, R.A.; Aaron, S.D. Assessment of Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm) Using Pre and Post Bronchodilator Spirometry in a Randomly-Sampled Symptomatic Cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 1129–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, D.H.; Granell, R.; Davey Smith, G.; Dodd, J.W. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: A UK Biobank cohort analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, D.H.; Lirio, A.; Hamilton, F.; Granell, R.; Wyss, A.B.; London, S.J.; Bartz, T.M.; Gharib, S.A.; Cho, M.H.; Wan, E.; et al. Genome-wide association study of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm). Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2300337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ora, J.; Rogliani, P. Clinical challenges in applying the new lung function test interpretive strategies: Navigating pitfalls and possible solutions. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2301439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, D.B.; James, M.D.; Vincent, S.G.; Elbehairy, A.F.; Neder, J.A.; Kirby, M.; Ora, J.; Day, A.G.; Tan, W.C.; Bourbeau, J.; et al. Physiological Characterization of Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry in the CanCOLD Study: Implications for Exertional Dyspnea and Exercise Intolerance. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 1314–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Petersen, H.; Qualls, C.; Meek, P.M.; Vazquez-Guillamet, R.; Celli, B.R.; Tesfaigzi, Y. Spirometric variability in smokers: Transitions in COPD diagnosis in a five-year longitudinal study. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, E.S.; Fortis, S.; Regan, E.A.; Hokanson, J.; Han, M.K.; Casaburi, R.; Make, B.J.; Crapo, J.D.; DeMeo, D.L.; Silverman, E.K.; et al. Longitudinal Phenotypes and Mortality in Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry in the COPDGene Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Borst, B.; Gosker, H.R.; Zeegers, M.P.; Schols, A.M.W.J. Pulmonary function in diabetes: A metaanalysis. Chest 2010, 138, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatrella, A.; Calabrese, C.; Mattiello, A.; Panico, C.; Costigliola, A.; Chiodini, P.; Panico, S. Abdominal adiposity is an early marker of pulmonary function impairment: Findings from a Mediterranean Italian female cohort. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liao, G.; Tse, L.A. Association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry with mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marott, J.L.; Ingebrigtsen, T.S.; Çolak, Y.; Vestbo, J.; Lange, P. Trajectory of Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry: Natural History and Long-Term Prognosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.S. The Clinical Spectrum of PRISm. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, J. Dysanapsis in normal lungs assessed by the relationship between maximal flow, static recoil, and vital capacity. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1980, 121, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Mead, J.; Turner, J.M. Variability of maximum expiratory flow-volume curves. J. Appl. Physiol. 1974, 37, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, S.; Ichikawa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Fukuchi, Y.; Takahashi, K. Practical surrogate marker of pulmonary dysanapsis by simple spirometry: An observational case-control study in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, M.; Hart, K.; Kotecha, S.J.; Henderson, A.J.; Watkins, W.J.; Bush, A.; Kotecha, S. Characterising airway obstructive, dysanaptic and PRISm phenotypes of prematurity-associated lung disease. Thorax 2023, 78, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arismendi, E.; Bantulà, M.; Perpiñá, M.; Picado, C. Effects of Obesity and Asthma on Lung Function and Airway Dysanapsis in Adults and Children. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, E3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.R.; Smith, J.R.; Luden, N.D.; Saunders, M.J.; Kurti, S.P. The Prevalence of Expiratory Flow Limitation in Youth Elite Male Cyclists. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, L.M.; Bennett, M.H.; Thomas, P.S. Pulmonary dysanapsis and diving assessments. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2009, 36, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tager, I.B.; Weiss, S.T.; Muñoz, A.; Welty, C.; Speizer, F.E. Determinants of response to eucapneic hyperventilation with cold air in a population-based study. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1986, 134, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, F.; Tanabe, N.; Shimada, T.; Iijima, H.; Sakamoto, R.; Shiraishi, Y.; Maetani, T.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, M.; Chubachi, S.; et al. Centrilobular emphysema and airway dysanapsis: Factors associated with low respiratory function in younger smokers. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00695–02023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.C.; San José Estépar, R.; Ash, S.; Pistenmaa, C.; Han, M.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bodduluri, S.; Sparrow, D.; Charbonnier, J.-P.; Washko, G.R.; et al. Dysanapsis is differentially related to lung function trajectories with distinct structural and functional patterns in COPD and variable risk for adverse outcomes. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, N.R.; McGowan, A.; Ramsey, K.A.; Borg, B.; Kivastik, J.; Knight, S.L.; Sylvester, K.; Burgos, F.; Swenson, E.R.; McCarthy, K.; et al. European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical statement: Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes, 2023 update. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, 2201519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaroni, C.; Carraro, E.; Vianello, A.; Miccinilli, S.; Morrone, M.; Levai, I.K.; Schena, E.; Saccomandi, P.; Sterzi, S.; Dickinson, J.W.; et al. Optoelectronic Plethysmography in Clinical Practice and Research: A Review. Respiration 2017, 93, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criée, C.P.; Sorichter, S.; Smith, H.J.; Kardos, P.; Merget, R.; Heise, D.; Berdel, D.; Köhler, D.; Magnussen, H.; Marek, W.; et al. Body plethysmography—Its principles and clinical use. Respir. Med. 2011, 105, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, A.B.; Botelho, S.Y.; Bedell, G.N.; Marshall, R.; Comroe, J.H. A rapid plethysmographic method for measuring thoracic gas volume: A comparison with a nitrogen washout method for measuring functional residual capacity in normal subjects. J. Clin. Investig. 1956, 35, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, M.; Islam, S.; Rangarajan, S.; Leong, D.; Kurmi, O.; Teo, K.; Killian, K.; Dagenais, G.; Lear, S.; Wielgosz, A.; et al. Mortality and cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity in individuals with impaired FEV1 (PURE): An international, community-based cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e613–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydell, A.; Janson, C.; Lisspers, K.; Lin, Y.-T.; Ärnlöv, J. FEV1 and FVC as robust risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mortality: Insights from a large population study. Respir. Med. 2024, 227, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, D.M.; Ford, E.S.; Redd, S.C. Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination. J. Intern. Med. 2003, 254, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel-Claussen, J.; Schönfeld, C.-O.; Kaireit, T.F.; Voskrebenzev, A.; Czerner, C.P.; Renne, J.; Tillmann, H.-C.; Berschneider, K.; Hiltl, S.; Bauersachs, J.; et al. Effect of Indacaterol/Glycopyrronium on Pulmonary Perfusion and Ventilation in Hyperinflated Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (CLAIM). A Double-Blind, Randomized, Crossover Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohlfeld, J.M.; Vogel-Claussen, J.; Biller, H.; Berliner, D.; Berschneider, K.; Tillmann, H.-C.; Hiltl, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Welte, T. Effect of lung deflation with indacaterol plus glycopyrronium on ventricular filling in patients with hyperinflation and COPD (CLAIM): A double-blind, randomised, crossover, placebo-controlled, single-centre trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Aisanov, Z.; Avdeev, S.; Di Maria, G.; Donner, C.F.; Izquierdo, J.L.; Roche, N.; Similowski, T.; Watz, H.; Worth, H.; et al. Mechanisms, assessment and therapeutic implications of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, D.E.; Webb, K.A.; Neder, J.A. Lung hyperinflation in COPD: Applying physiology to clinical practice. COPD Res. Pract. 2015, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ora, J.; Giorgino, F.M.; Bettin, F.R.; Gabriele, M.; Rogliani, P. Pulmonary Function Tests: Easy Interpretation in Three Steps. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133655

Ora J, Giorgino FM, Bettin FR, Gabriele M, Rogliani P. Pulmonary Function Tests: Easy Interpretation in Three Steps. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133655

Chicago/Turabian StyleOra, Josuel, Federica Maria Giorgino, Federica Roberta Bettin, Mariachiara Gabriele, and Paola Rogliani. 2024. "Pulmonary Function Tests: Easy Interpretation in Three Steps" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133655

APA StyleOra, J., Giorgino, F. M., Bettin, F. R., Gabriele, M., & Rogliani, P. (2024). Pulmonary Function Tests: Easy Interpretation in Three Steps. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133655