1. Introduction

Oral surgery is a fundamental component of dental practice, with university curricula worldwide aiming to produce graduates who are competent within the full scope of general dentistry [

1,

2,

3]. In Australia, there is a noticeable trend at recently established dental schools to place an emphasis on theoretical knowledge in oral surgery, without significant complementary practical experience in the discipline [

2]. For the majority of modern dental students, practical exposure to oral surgery is limited in the preclinical environment, with students expected to develop skills in exodontia under the supervision of a general dentist [

2]. Inadequate exposure to practical oral surgical skills may lead to reduced confidence in oral surgery upon graduation, as well as extended waiting times for specialist referrals [

4].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical and dental education has also been a source of concern, particularly where electronic and digital formats have superseded or reduced the usual exposure of dental students to oral surgery [

5]. Therefore, it is important for dental educators to reflect on which components of online education should be retained, and which areas would benefit from increasing the emphasis on practical skills.

Australian dental educators were among the first reported in the literature to use porcine heads for the formal teaching of oral surgery in dental schools [

6]. The low cost, wide abundance, limited regulatory requirements and simple preparation of porcine heads have made them an ideal teaching model for many years [

7,

8]. Fresh porcine heads are far easier to obtain than fresh human tissue, and in many countries, require far less ethical consideration. However, there are distinct differences between the human and porcine craniofacial complex, most notably the different dentition and thicker soft tissue consistency [

9,

10]. Porcine heads are frequently used in postgraduate surgical teaching, but there are only limited reports of its use in modern undergraduate (pre-doctoral) dental education [

8]. They are commonly used by otolaryngologists, dermatologists, as well as other dental specialties in the training of their residents [

10,

11,

12].

Dental schools commonly face pressures to provide a curriculum for their students that accounts for an ever-expanding knowledge base in dentistry. Condensing this knowledge into a fixed timeframe may have resulted in surgical skill training being neglected at the pre-doctoral level, in favour of greater exposure to advances in restorative and aesthetic procedures [

13]. Furthermore, there has been a general trend in dental education where procedural skills are no longer practiced on cadaveric tissue in favour of virtual reality simulation [

14,

15].

When designing improvements in modern dental curricula, teaching institutions must place great consideration on feedback from the experience of current students [

16,

17]. The aim of this pilot study was to assess the benefit of using porcine heads as a medium-fidelity model in surgical skill training for third-year undergraduate dental students. To determine the usefulness of this model, students were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire pertaining to the following: the student’s self-assessment of previous training in dentoalveolar surgery (

Experience), the usefulness of the porcine model for training (

Teaching), and how closely the model matched theoretical understanding (

Theory) and simulated the relevant clinical scenario (

Representation).

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Griffith University, Gold Coast Australia, Human Research Ethics Committee 4 September 2023 (ref. no.: 2023/624).

Thirty volunteers were recruited for this study. All participants were third-year undergraduate (pre-doctoral equivalent) students in a five-year dentistry program at Griffith University, Gold Coast in Australia. Graduates of the program are eligible for full registration as dentists in Australia and New Zealand, and have reciprocity of training equivalency with Canada. At the time of this study, all students had received one full semester of oral surgery theory education and were familiar with the armamentarium for basic procedures. The third-year cohort was chosen for this activity as they would be expected to perform dental extractions at the university clinic from the commencement of their fourth year.

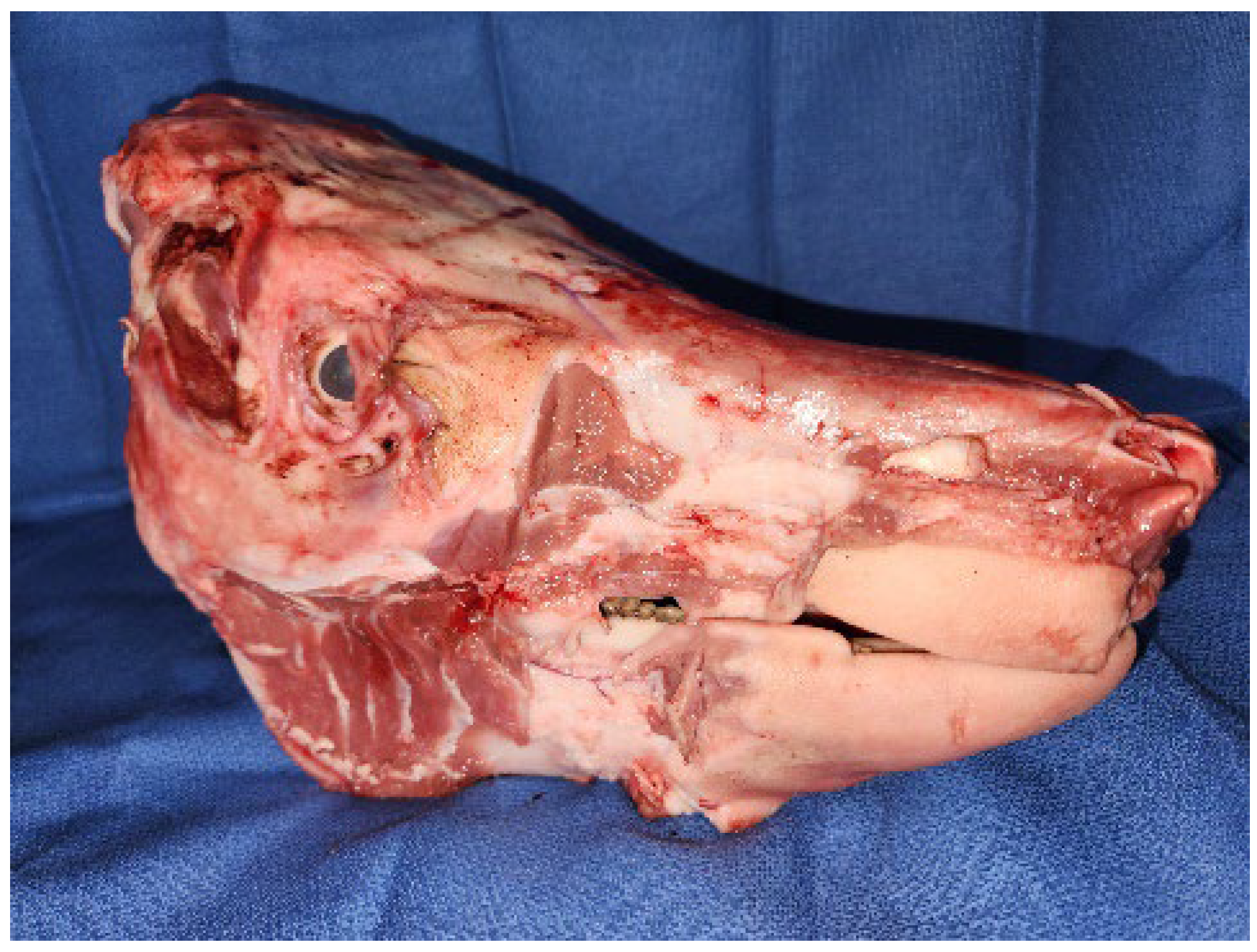

Thirty whole heads were disarticulated at the atlanto-occipital joint from the carcass of commercially farmed pigs (

Sus domesticus) and processed under Australian food safety standards at a local abattoir (Warwick, QLD, Australia). Each head was purchased for AUD 5.00 (approx. USD 3.30). They were stored at our institution for up to 48 h in a cool room at 4 °C, and set up on blue absorbent pads 1 h prior to teaching, as shown in

Figure 1.

Participants attended a single two-hour session that involved a 30 min lecture in basic oral surgery procedures and a 90 min hands-on workshop with porcine heads. The lecture was delivered by a specialist academic oral and maxillofacial surgeon (M.H.), who presented a step-by-step process for the procedures to be completed in the workshop. The hands-on activity involved making a crestal incision through the gingiva of the porcine mandible, raising a mucoperiosteal flap to the level of the molar apices and completing the activity by suturing the flap closed. In addition to a maxillofacial surgeon, students were supervised by two surgical residents and three general dentists (faculty-to-student ratio 1:5).

Students were provided with a standard oral surgery armamentarium that included the following: iris scissors, cotton tweezers, Adson forceps, #15 scalpel blade, scalpel handle, Molt periosteal elevator #9, needle holder and 4/0 nylon sutures with a reverse cutting tip. Participants were instructed to expose the porcine heads through the buccal skin and mucosa to provide better access to the oral cavity (

Figure 2).

At the conclusion of the workshop, participants were provided with an anonymous questionnaire sheet that included eight prompts presented on a 5-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree, 2: Somewhat disagree, 3: Neutral, 4: Somewhat agree, 5: Strongly agree).

The following prompts were included in the questionnaire:

Prior to this workshop I have studied the theory of raising mucoperiosteal flaps in my dental school curriculum.

Prior to this workshop I have studied the theory of raising mucoperiosteal flaps external to my dental school curriculum.

Prior to this workshop I have assisted raising mucoperiosteal flaps.

Prior to this workshop I have raised mucoperiosteal flaps.

Using the hands-on pig head model helped me relate my previous knowledge and match the practical exercise with theory.

The pig head model was representative of what I expect to see clinically when raising mucoperiosteal flaps.

Overall, I found that using the pig head model was useful for my dental education.

I would practice raising mucoperiosteal flaps in a pig head model again.

Data from all questionnaires were assigned a numerical code and transcribed electronically into Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, DC, USA) for preliminary analysis. All hard copies of the questionnaires were securely destroyed using local document utility services, as per our institutional protocol.

3. Results

Of the thirty participants, twenty-eight completed the questionnaire, and two participants returned an incomplete form to the response collection box (93.33% completion rate). As all responses were anonymous, participants who did not complete the questionnaire were unable to be followed up.

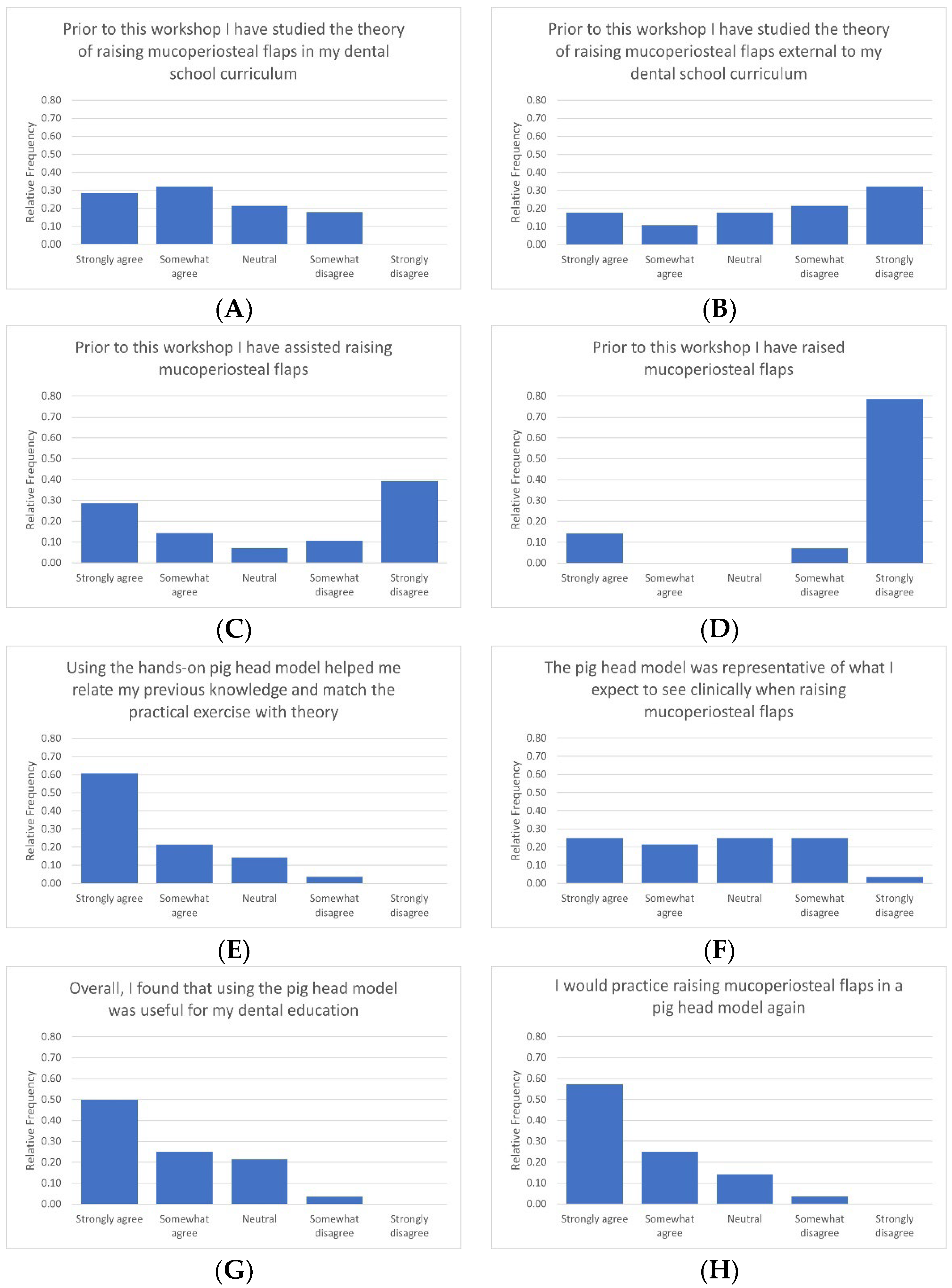

The results from the questionnaire are summarised in

Figure 3. Prior to the workshop, two-thirds (61%) of participants felt that they had been taught the surgical procedure for raising mucoperiosteal flaps adequately in their dental school curriculum and only one-third (29%) of students reported studying the theory external to the dental school curriculum. Less than half of the students (43%) reported having experience in assisting specialty residents raising a mucoperiosteal flap, and only 14% reported having performed the procedure themselves.

Seventy percent of the students agreed that the model was representative of what they have or expected to see clinically, and only 4% of students felt that the session did not help in relating prior theoretical knowledge. Almost all students (96%) agreed that the porcine model was useful for their dental education and that they would practice the exercise using the model again if provided with the opportunity (96%).

4. Discussion

The competence of dental students in oral surgery requires a balance between theoretical understanding and clinical practice [

2]. Intentional practice on a representative model is a critical aspect of developing expertise in any surgical discipline and forms the basis for many surgical training programs [

18]. The opportunity to experience haptic feedback allows for clinicians to develop confidence performing the procedure, as well as understanding its indications and contraindications, and the purpose of each instrument in their armamentarium. It is equally important that the development of practical skills is conducted in an environment and on a model that is perceived to be useful [

17]. While other models such as periodontal typodonts and virtual simulation exist as alternatives to porcine tissue, they do not provide haptic feedback when raising the periosteum to the same level [

14,

19]. We did not use human cadaveric material due to the extensive and expensive logistical and ethical limitations of using fresh tissue in our jurisdiction. On the other hand, using pig heads from a local commercial abattoir posed far less ethical restrictions under our institutional protocol.

Dental students in their third year of study at Griffith University are exposed to pre-recorded lectures on the theory of oral surgery, as well as an explanation on how to use basic surgical instruments. The results of the questionnaire indicated that 70% of the students were in a phase where the opportunity for practical skill training was able to complement their theoretical understanding in raising an oral mucoperiosteal flap. As a medium-fidelity model, porcine heads are not solely adequate for oral surgery training but do provide a method that preclinical students find useful for developing practical skills in oral surgery. Within the cohort, there was a distinct group (29%) that benefited the most from this activity—those who had completed theoretical training but had not yet assisted a surgeon during their mandatory placement hours. During their mandatory assisting hours, it is possible that an oral surgeon had encouraged a student to perform part of the procedure, and this could account for outliers with respect to experience, despite all students being in the third year of their pre-doctoral program.

Goss et al. [

2] reported that fewer than half of the dental schools throughout Australia and New Zealand taught dentoalveolar surgery in dedicated oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMS) clinics under direct supervision of surgically trained staff. They found that while all schools provided education regarding the removal of impacted teeth, none expected students to be competent in doing so upon graduation. The opportunity to attend an OMS-directed workshop in practical oral surgical skills may therefore lead to improved understanding and confidence of dental students upon graduation.

This pilot study demonstrated that 96% of students responded favourably to the use of a porcine model in the development of their learning. The modality of porcine heads may also lead to improved patient outcomes, as students would have better technical skills by practicing on a medium-fidelity-representation model prior to treating human patients. The authors hope that this pilot study promotes the implementation of further practical wet-lab workshops in the modern dental curriculum, with a focus on providing pre-clinical students with adequate training in practical skills.

5. Conclusions

Overall, third-year Australian dental students at Griffith University found that using porcine heads was a useful adjunct to learning basic oral surgical procedures. Compared to other training models, porcine heads are a relatively low-cost investment for educators and present a unique opportunity for dental students to seek feedback on their surgical skills prior to treating patients. We hope that this pilot study encourages more dental schools to incorporate practical surgical skills training in their curriculum, with a focus on improving patient outcomes and the confidence of their students upon graduation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., M.H. and J.D.; methodology, Y.G. and M.F.; formal analysis, Y.G. and M.F.; investigation, Y.G., M.H., K.S. and J.D.; resources, M.H.; data curation, J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, K.S., M.H. and M.F.; visualization, J.D. and Y.G.; supervision, M.H. and M.F.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Southern Implants Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. no.: 2023/624), approval of date: 4 September 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study as per the Institutional Review Board requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Southern Implants Australia for providing the surgical instruments, and Theresa Gaynor Acting Facility Manager from the Griffith University Anatomy Facility for providing logistical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Macluskey, M.; Durham, J. Oral surgery undergraduate teaching and experience in the United Kingdom: A national survey. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2009, 13, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A. The teaching of oral & maxillofacial surgery to dental students in Australia & New Zealand. Aust. Dent. J. 2018, 63 (Suppl. S1), S114–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, H.S.; Van Der Cammen, C.C.J.; Roorda, S.M.E.; Baart, J.A. Tooth extraction education at dental schools across Europe. BDJ Open 2015, 1, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Sivarajasingam, V.; Morgan, M.Z. An investigation into oral surgery referrals in Wales. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A.R.D.S.; Hsu, J.; Carter, E.F.; Ullah, M.; Oam, S.C.C. Dental student oral surgery training—Comparing the impact of COVID-19 and cohort sizes. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 27, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, G.C. The pig’s head as a teaching device in oral surgery. Aust. Dent. J. 1967, 12, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, G.C. A laboratory for teaching oral-surgical technique. J. Dent. 1985, 13, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Shi, D.; Wang, C.; Zhen, M.; Wei, Y.; Han, Z.; Hu, W.; Chung, K. Assessment of a developed pig cadaver model for teaching crown lengthening surgical procedures. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, F.; Koerdt, S.; Rommel, N.; Wolff, K.; Kesting, M.; Weitz, J. Reconstruction of facial defects with local flaps—A training model for medical students? Head Face Med. 2015, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyllar, M.; Štembírek, J.; Daněk, Z.; Hodan, R.; Stránský, J.; Machoň, V.; Foltán, R. A porcine model: Surgical anatomy of the orbit for maxillofacial surgery. Lab. Anim. 2015, 50, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara, R.T.; Rasberry, R.D. Pig head model for practice cutaneous surgery. Dermatol. Surg. 2000, 26, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zeng, N.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Shi, B.; Cheng, X. The pilot study of a blended learning module using porcine tongue for surgical simulation of double-opposing Z-plasty. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 87, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landes, C.A.; Hoefer, S.; Schuebel, F.; Ballon, A.; Teiler, A.; Tran, A.; Weber, R.; Walcher, F.; Sader, R. Long-term prospective teaching effectivity of practical skills training and a first OSCE in Cranio Maxillofacial Surgery for dental students. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, e97–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, J. Survey on multisensory feedback virtual reality dental training systems. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 20, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, M.P.; Moreira, A.; Pinto, J.C.; Amarante, J.; Mendes, J. The Challenge of Dental Education After COVID-19 Pandemic—Present and Future Innovation Study design. Inquiry 2021, 58, 004695802110182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henzi, D.; Davis, E.; Jasinevicius, R.; Hendricson, W.D. In the Students’ Own Words: What Are the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Dental School Curriculum? J. Dent. Educ. 2007, 71, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabbar, F.; Burdurlu, M.Ç.; Tomruk, C.Ö.; Bank, B.; Atalay, B. Students’ perspectives on undergraduate oral surgery education. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Kazmierczak, E.; Stern, L.; Smith, A.C.; Wise, L.; Field, B.W. Towards Defining Dental Drilling Competence, Part 1: A Study of Bone Drilling Technique. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 74, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswaran, S.V.K.; Dowlatshahi, S.; Weltman, R.; Zhu, L.; Elangovan, S.; Lee, C. Preclinical teaching of periodontal surgical concepts using common instructional models: A comparative assessment. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 87, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).