Frailty and Increased Levels of Symptom Burden Can Predict the Presence of Each Other in HNSCC Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Statistical Considerations and Sample Size

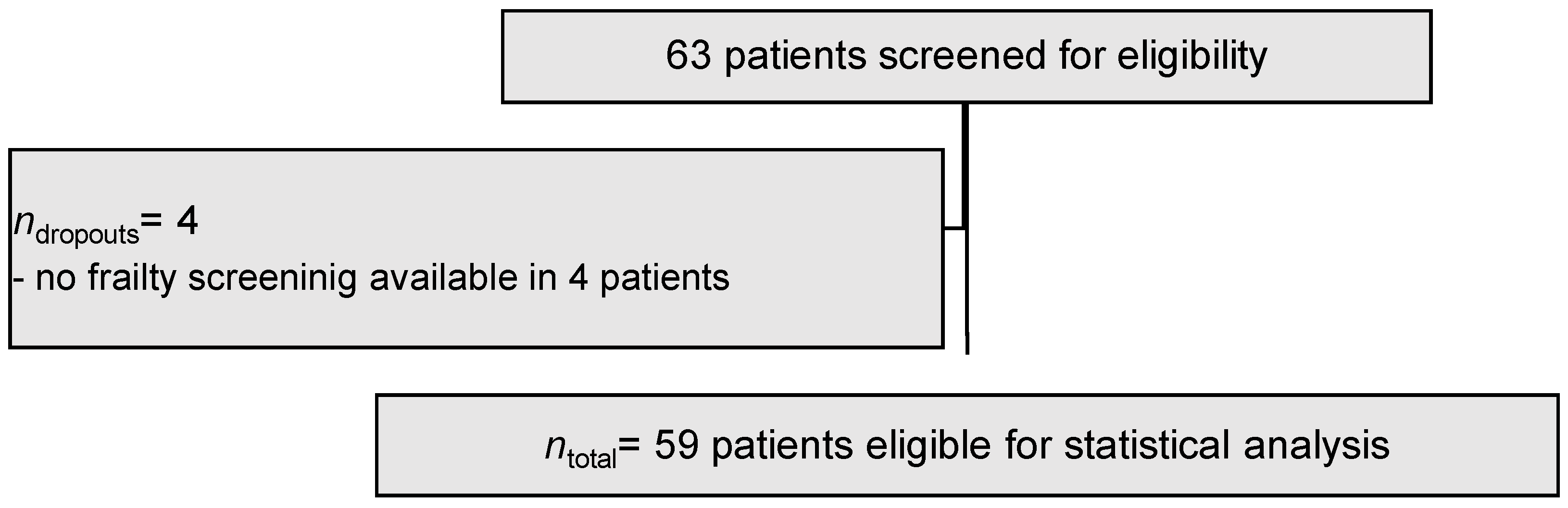

2.2. Study Cohort

2.3. Assessment of Frailty and Symptom Burden

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Parameters and Study Cohort

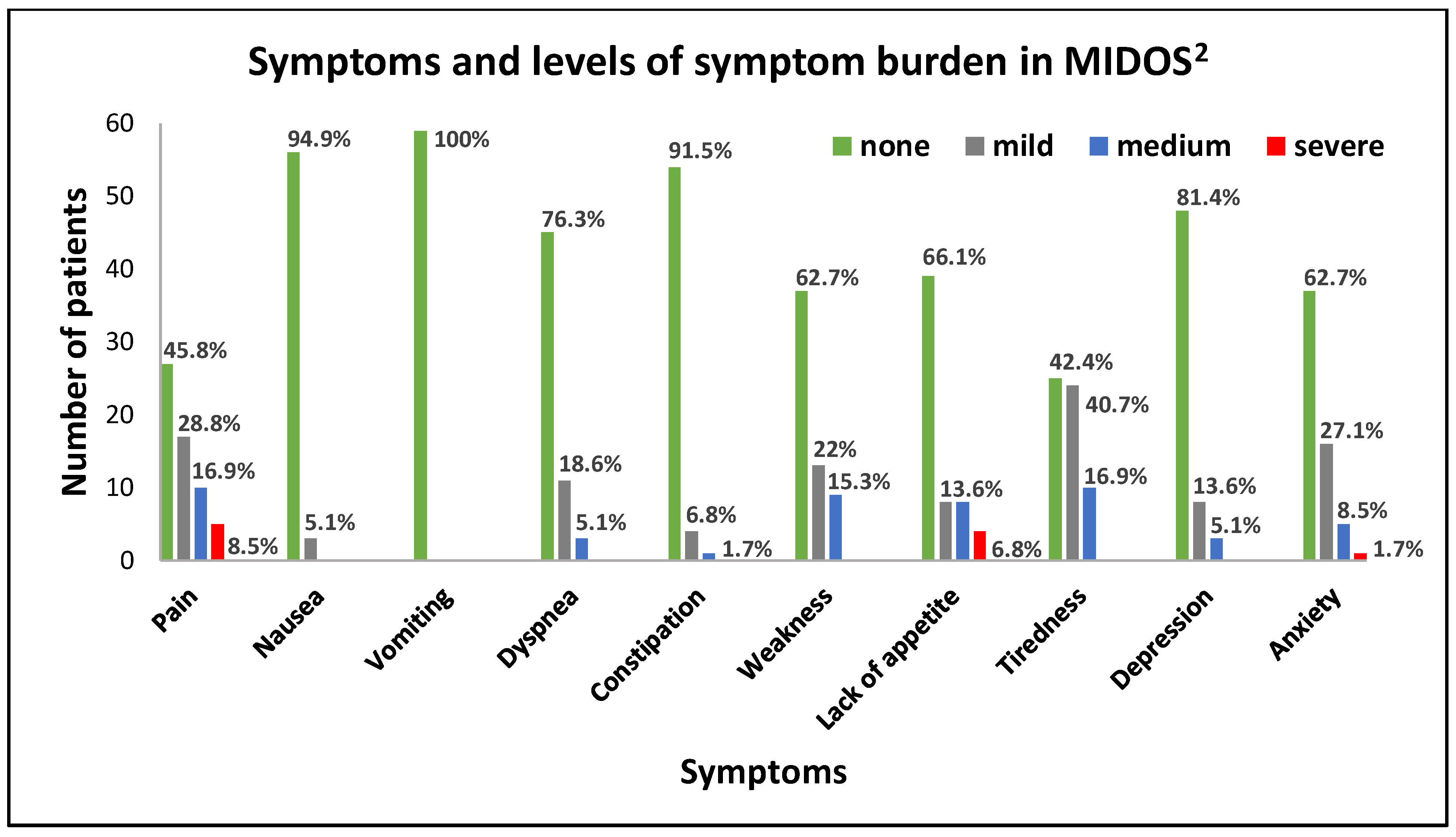

3.2. Symptoms and Symptom Burden

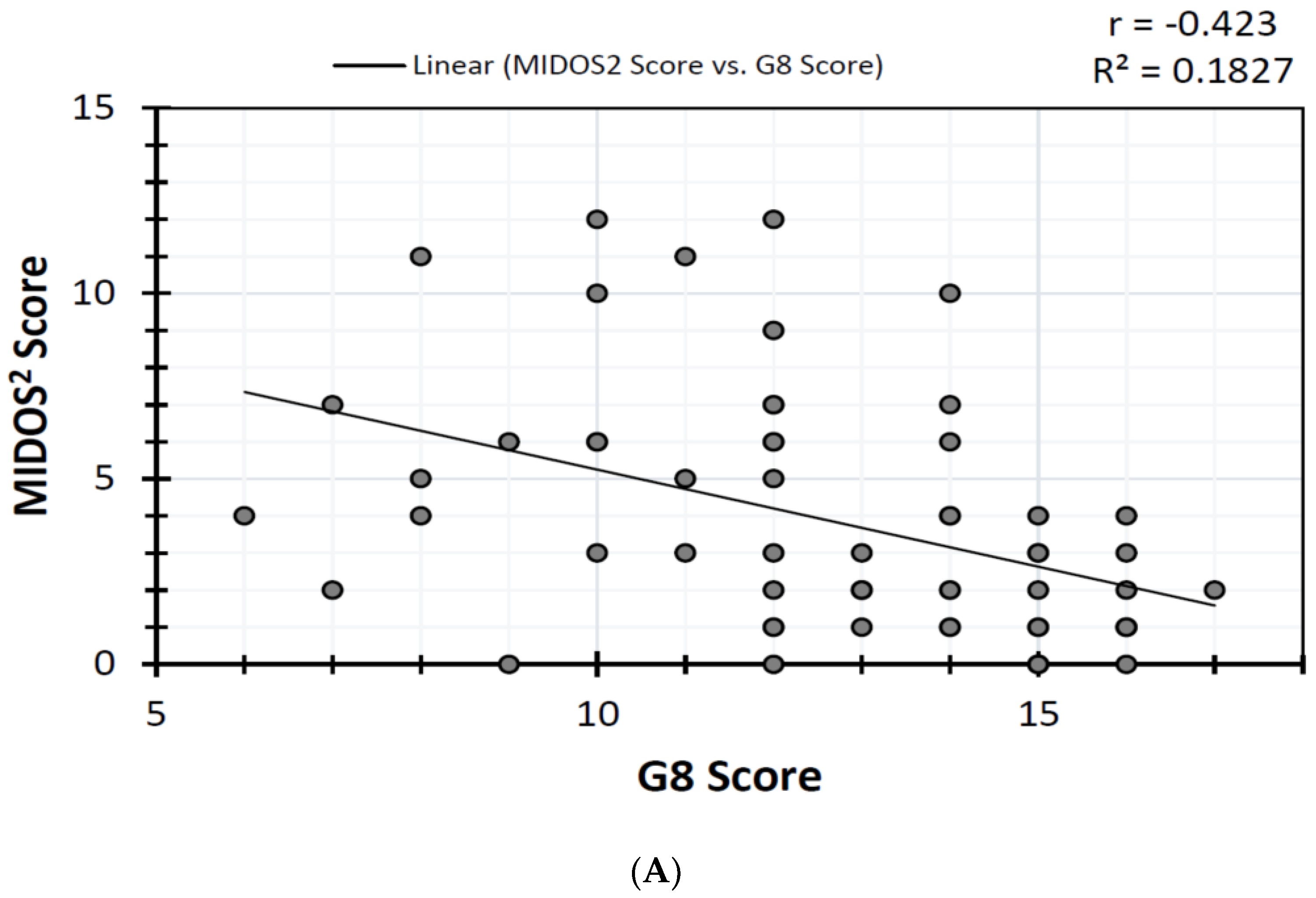

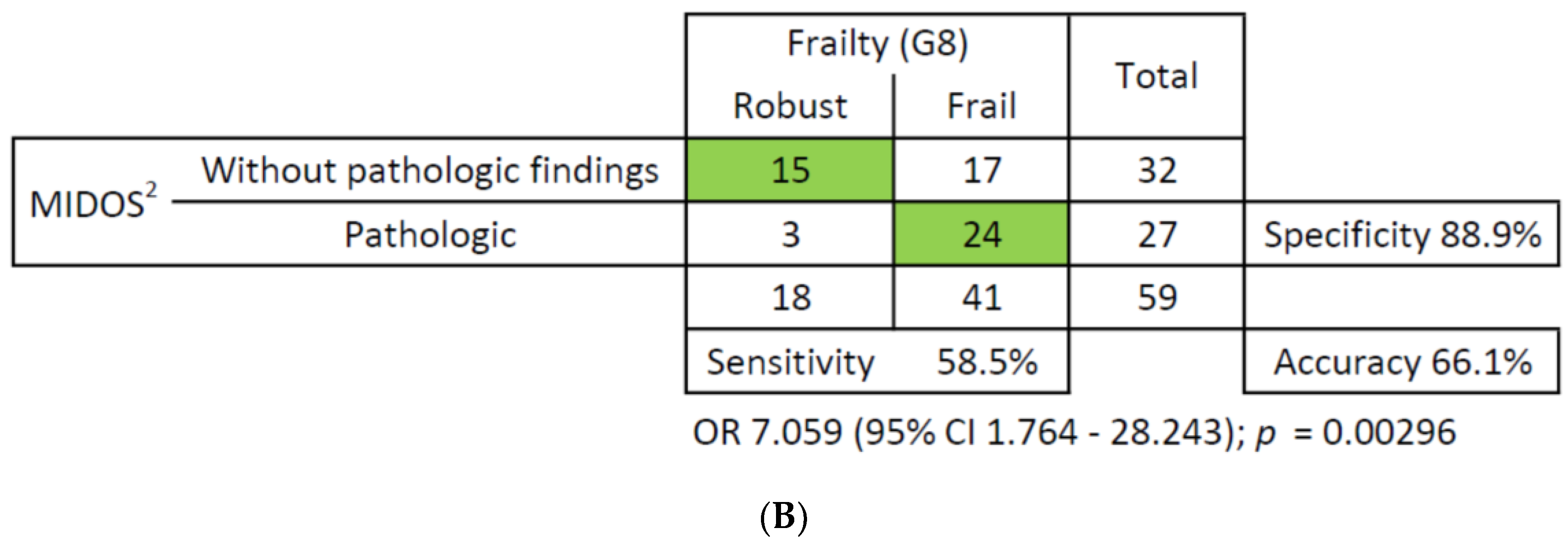

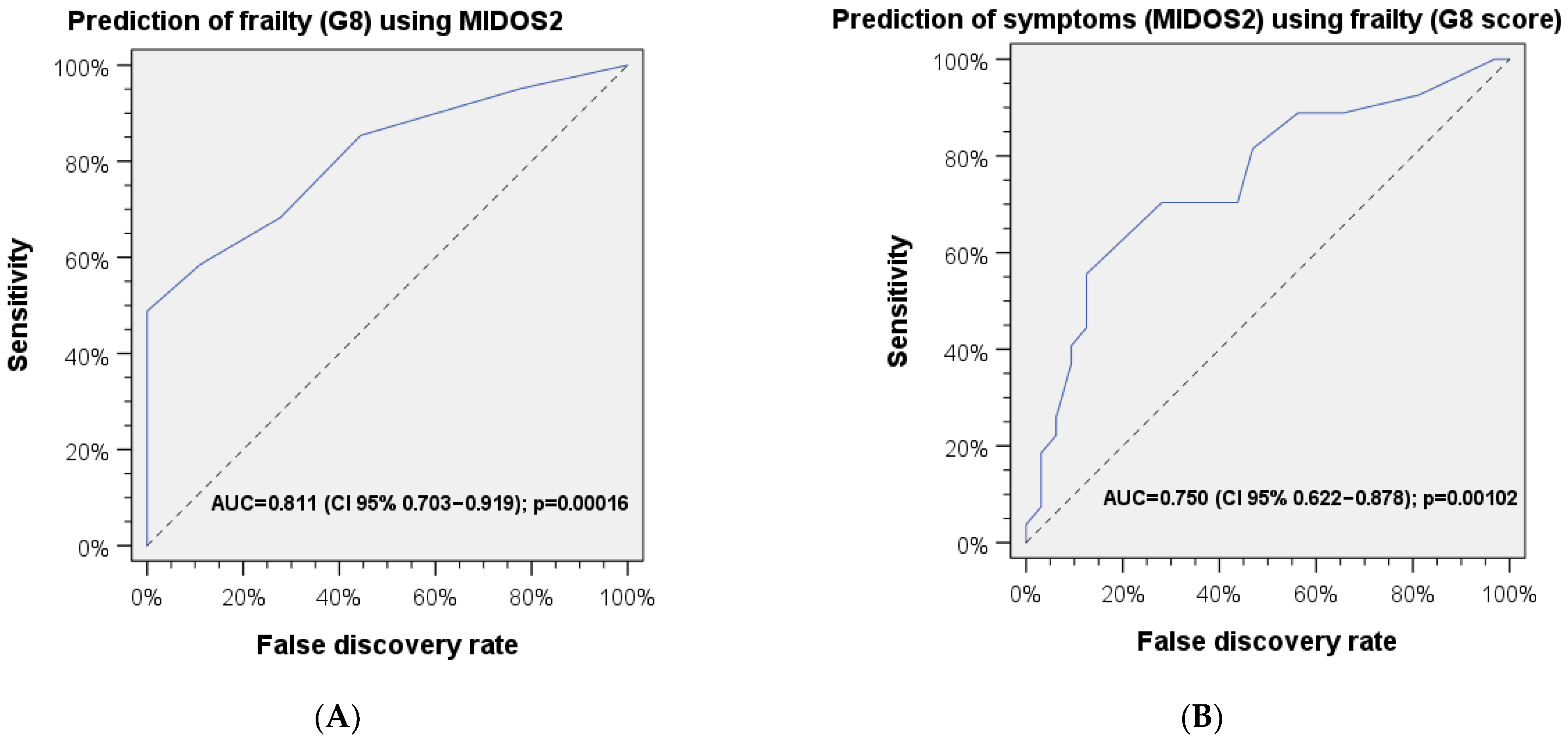

3.3. Correlations and ROC Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CGA | Comprehensive geriatric assessment |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CUP | Cancer of unknown primary |

| G8 | Geriatric 8 (screening instrument for the assessment of frailty) |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IBM | International Business Machines Corporation |

| J | Youden’s J |

| MIDOS2 | Minimal Documentation System 2 |

| n | Sample size |

| p | p-value |

| ρ | Spearman’s rho |

| r | Pearson’s r |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic (used to assess the accuracy of tests in predictive models) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| Zalpha | Standardized distance from mean (according to standard deviation units) |

References

- Kunz, V.; Wichmann, G.; Wald, T.; Pirlich, M.; Zebralla, V.; Dietz, A.; Wiegand, S. Frailty Assessed with FRAIL Scale and G8 Questionnaire Predicts Severe Postoperative Complications in Patients Receiving Major Head and Neck Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.J.G.; Frizelle, F.A.; Geddes, J.A.; Eglinton, T.W.; Hampton, M.B. Frailty in surgical patients. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2018, 33, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Ma, T.; Cui, W.; Li, T.; Liu, D.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Fu, Y. Frailty and long-term survival of patients with colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostoft, S.; O’Donovan, A.; Soubeyran, P.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Hamaker, M.E. Geriatric Assessment and Management in Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, W.B.; Rosenthal, R.A.; Merkow, R.P.; Ko, C.Y.; Esnaola, N.F. Optimal Preoperative Assessment of the Geriatric Surgical Patient: A Best Practices Guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 215, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, C.H.; Hsu, T. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the Older Adult with Cancer: A Review. Eur. Urol. Focus 2017, 3, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, T.R.; Kehl, K.L.; Bamidele, O.; Williams, L.A.; Shi, Q.; Cleeland, C.S.; Simon, G. Assessment of baseline symptom burden in treatment-naïve patients with lung cancer: An observational study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3439–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, R.A.; Nipp, R.D.; Waldman, L.P.; Greer, J.A.; Lage, D.E.; Hochberg, E.P.; Jackson, V.A.; Fuh, C.; Ryan, D.P.; Temel, J.S.; et al. Symptom burden in patients with cancer who are experiencing unplanned hospitalization. Cancer 2020, 126, 2924–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, A.; Majoufre, C.; De Boutray, M.; Gal, J.; Chamorey, E.; Roussel, L.-M.; Philouze, P.; Testelin, S.; Coninckx, M.; Bach, C.; et al. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer surgery with free-flap reconstruction in the elderly: Factors associated with long-term quality of life, patient needs and concerns. A GETTEC cross-sectional study. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 35, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.; Bras, L.; Sidorenkov, G.; Festen, S.; Steenbakkers, R.J.; Langendijk, J.A.; Witjes, M.J.; van der Laan, B.F.; de Bock, G.H.; Halmos, G.B. Frailty is associated with decline in health-related quality of life of patients treated for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020, 111, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.G.; Laurent, M.; Barnay, T.; Martínez-Tapia, C.; Audureau, E.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Aparicio, T.; Rollot-Trad, F.; Soubeyran, P.; Bellera, C.; et al. A Two-Step Frailty Assessment Strategy in Older Patients With Solid Tumors: A Decision Curve Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pélissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiel, S.; Matthes, M.; Bertram, L.; Ostgathe, C.; Elsner, F.; Radbruch, L. Validierung der neuen Fassung des Minimalen Dokumentationssystems (MIDOS2) für Patienten in der Palliativmedizin. Der Schmerz 2010, 24, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A Simple Method for the Assessment of Palliative Care Patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, C.W.; Forner, D.; Chepeha, D.B.; Baran, E.; Chan, K.K.; Parmar, A.; Husain, Z.; Karam, I.; Hallet, J.; Coburn, N.G.; et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: A narrative review of a standardized symptom assessment tool in head and neck oncology. Oral Oncol. 2021, 123, 105595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, A.; Schulz, S.M.; Schmitter, M.; Müller-Richter, U.; Kübler, A.; Kasper, S.; Hartmann, S. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Quality of Life Aspects in Patients with Recurrent/Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M.; Hahn, D.; Wolber, P.; Hautmann, M.G.; Reichert, D.; Weniger, S.; Belka, C.; Bergmann, T.; Göhler, T.; Welslau, M.; et al. Treatment response lowers tumor symptom burden in recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwal, S.P.; Singh, R.; Sanghavi, P.R.; Patel, H.; Anandi, Q. Correlation between Symptom Burden and Perceived Distress in Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: A Prospective Observational Study. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2021, 27, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Ayodabo, C.O.; Eskander, A.; Davis, L.E.; Zhao, H.; Mahar, A.L.; Karam, I.; Singh, S.; Gupta, V.; Bubis, L.D.; Moody, L.; et al. Symptom burden among head and neck cancer patients in the first year after diagnosis: Association with primary treatment modality. Oral Oncol. 2019, 99, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelond, S.; Ward, J.; Lambert, P.J.; Kim, C.A. Symptom Burden of Patients with Advanced Pancreas Cancer (APC): A Provincial Cancer Institute Observational Study. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.C.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Young, H.; Taal, M.W.; Pendleton, N.; Mitra, S.; Brady, M.E.; Dhaygude, A.P.; Smith, A.C. Symptom-burden in people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.X.; Bischoff, K.E.; Kent, D.S.; O’riordan, D.L.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Lai, J.C. Frailty is strongly associated with self-reported symptom burden among patients with cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33 (Suppl. S1), e395–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.P.; Sklar, M.C.; de Almeida, J.R.; Gilbert, R.; Gullane, P.; Irish, J.; Brown, D.; Higgins, K.; Enepekides, D.; Xu, W.; et al. Frailty as a predictor of outcomes in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E340–E345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, M.; Hutcheson, K.; Zaveri, J.; Lewin, J.; E Kupferman, M.; Hessel, A.C.; Goepfert, R.P.; Gunn, G.B.; Garden, A.S.; Ferraratto, R.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes of symptom burden in patients receiving surgical or nonsurgical treatment for low-intermediate risk oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A comparative analysis of a prospective registry. Oral Oncol. 2019, 91, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 49 | 83.1 |

| Female | 10 | 16.9 | |

| HNSCC site | Oropharynx | 23 | 39.0 |

| Larynx | 15 | 25.4 | |

| Oral cavity | 13 | 22.0 | |

| Hypopharynx | 6 | 10.2 | |

| CUP | 2 | 3.4 | |

| Frailty (G8) | Robust | 18 | 30.5 |

| Frail | 41 | 69.5 | |

| Increased symptom burden | Yes | 27 | 45.8 |

| (MIDOS2) | No | 32 | 54.2 |

| Age | MIDOS2 Score | G8 | |

| Mean | 62.53 | 3.86 | 12.47 |

| SD | 10.23 | 3.27 | 2.70 |

| Minimum | 35 | 0 | 6 |

| Maximum | 81 | 12 | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kunz, V.; Wichmann, G.; Wald, T.; Dietz, A.; Wiegand, S. Frailty and Increased Levels of Symptom Burden Can Predict the Presence of Each Other in HNSCC Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010212

Kunz V, Wichmann G, Wald T, Dietz A, Wiegand S. Frailty and Increased Levels of Symptom Burden Can Predict the Presence of Each Other in HNSCC Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(1):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010212

Chicago/Turabian StyleKunz, Viktor, Gunnar Wichmann, Theresa Wald, Andreas Dietz, and Susanne Wiegand. 2024. "Frailty and Increased Levels of Symptom Burden Can Predict the Presence of Each Other in HNSCC Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 1: 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010212

APA StyleKunz, V., Wichmann, G., Wald, T., Dietz, A., & Wiegand, S. (2024). Frailty and Increased Levels of Symptom Burden Can Predict the Presence of Each Other in HNSCC Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010212