Clinical Correlates of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches: An Observational Study in Child Cohorts

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The prevalence of osmophobia in the different forms of primary headaches among a population of children from two headache centers from January 2017 to January 2021.

- (2)

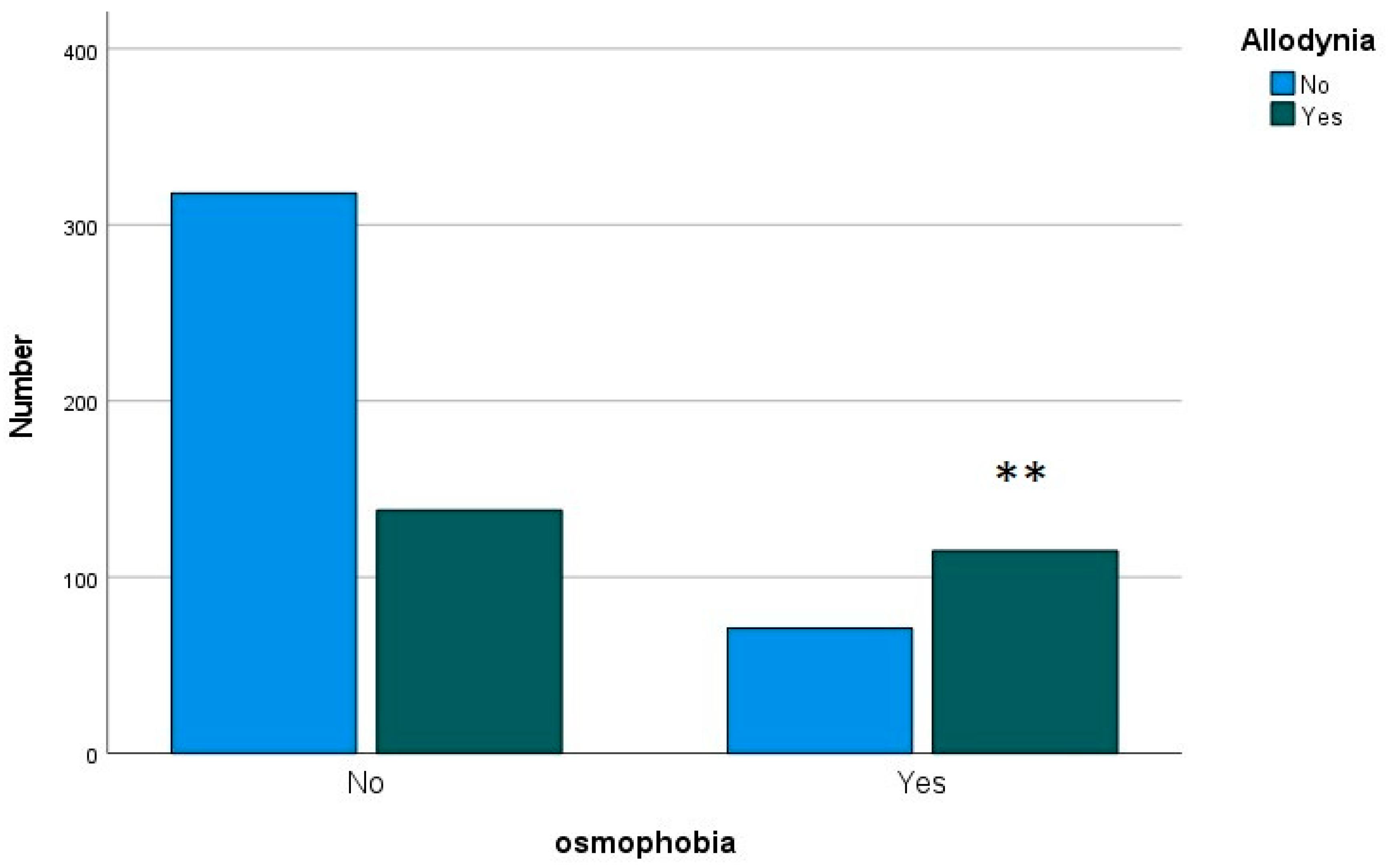

- The features of children suffering from headaches and reporting osmophobia in terms of headache frequency, intensity and association with allodynia.

- (3)

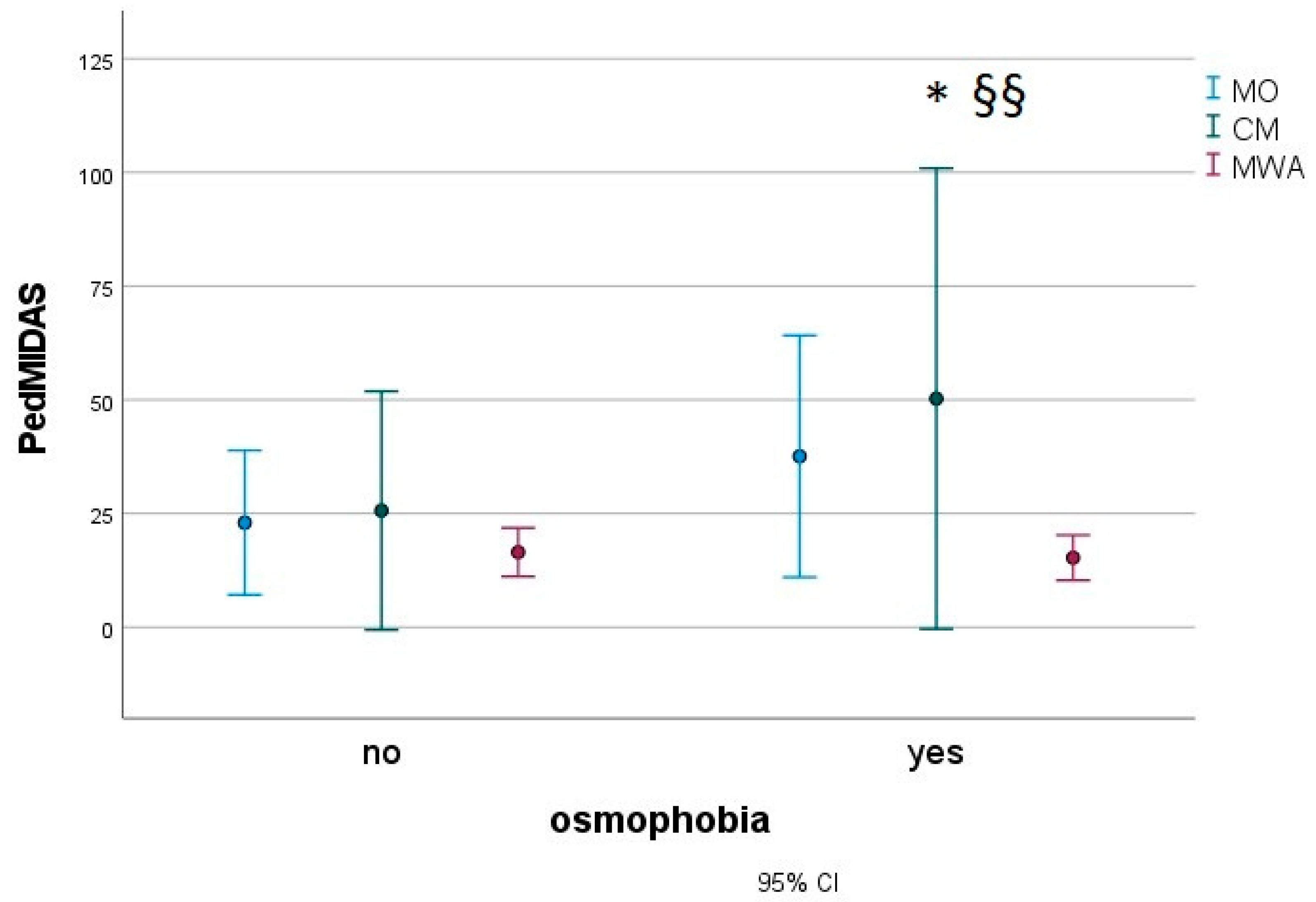

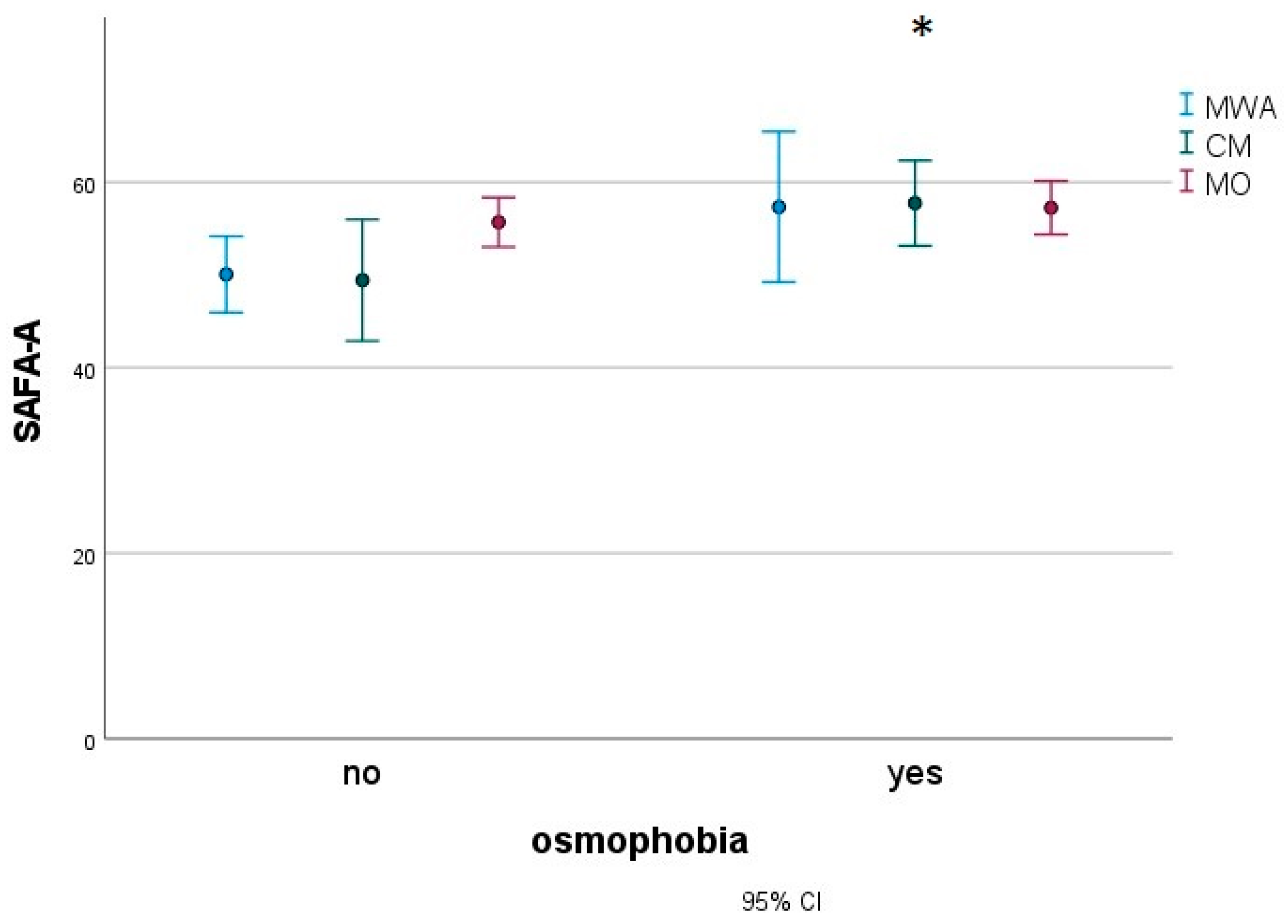

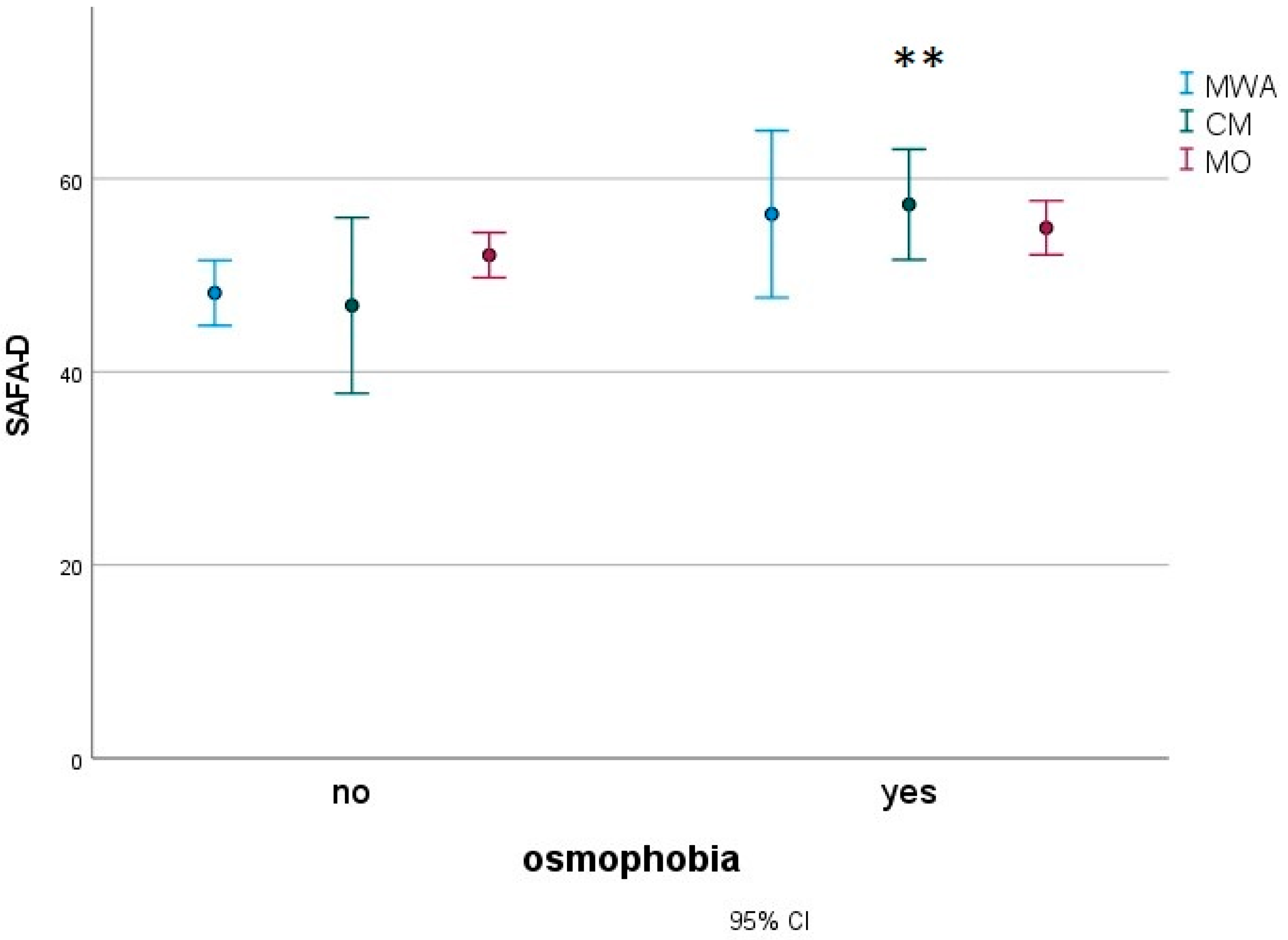

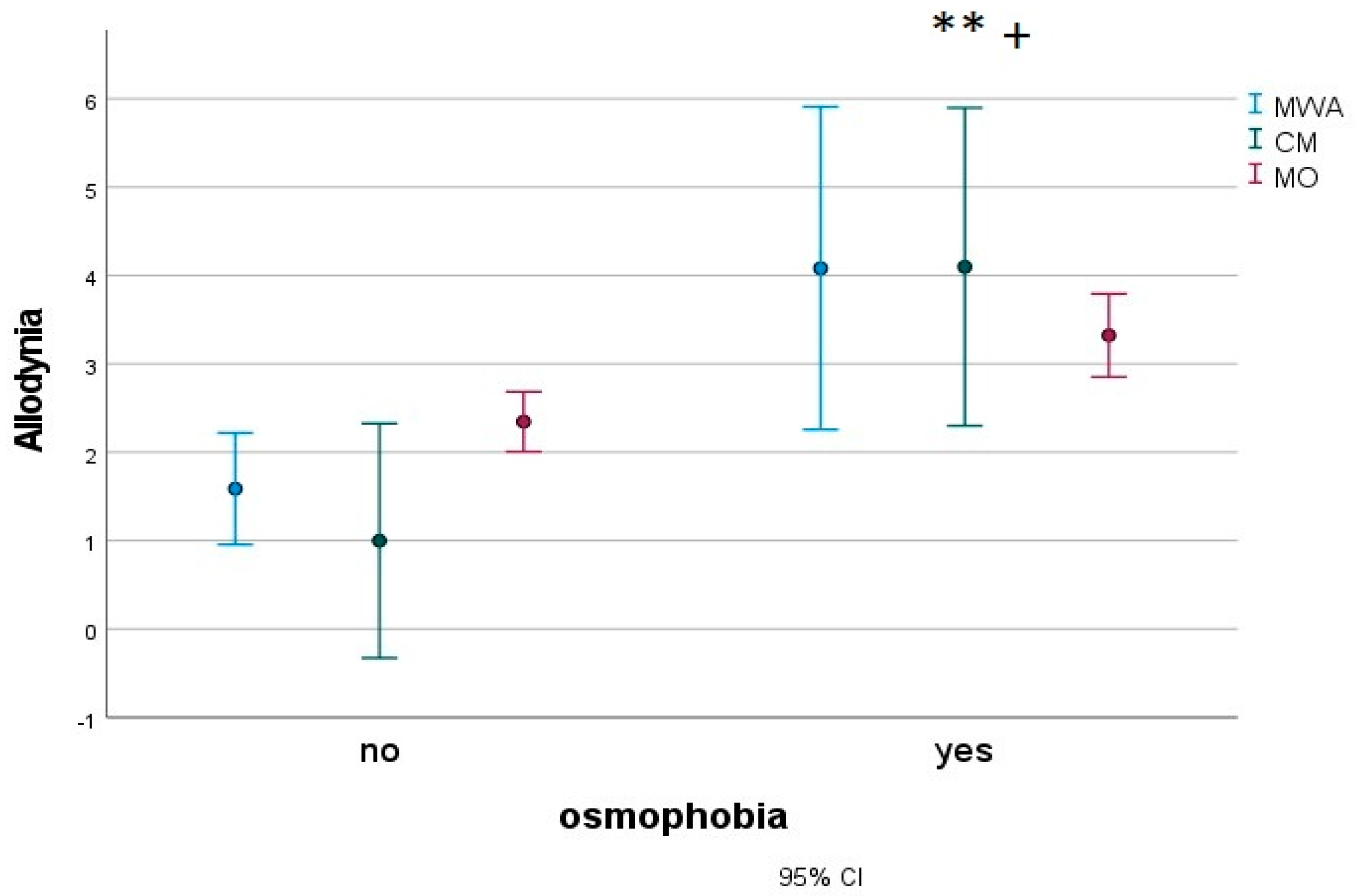

- The association between osmophobia and migraine-related disability, anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophizing in a subset of children suffering from migraines.

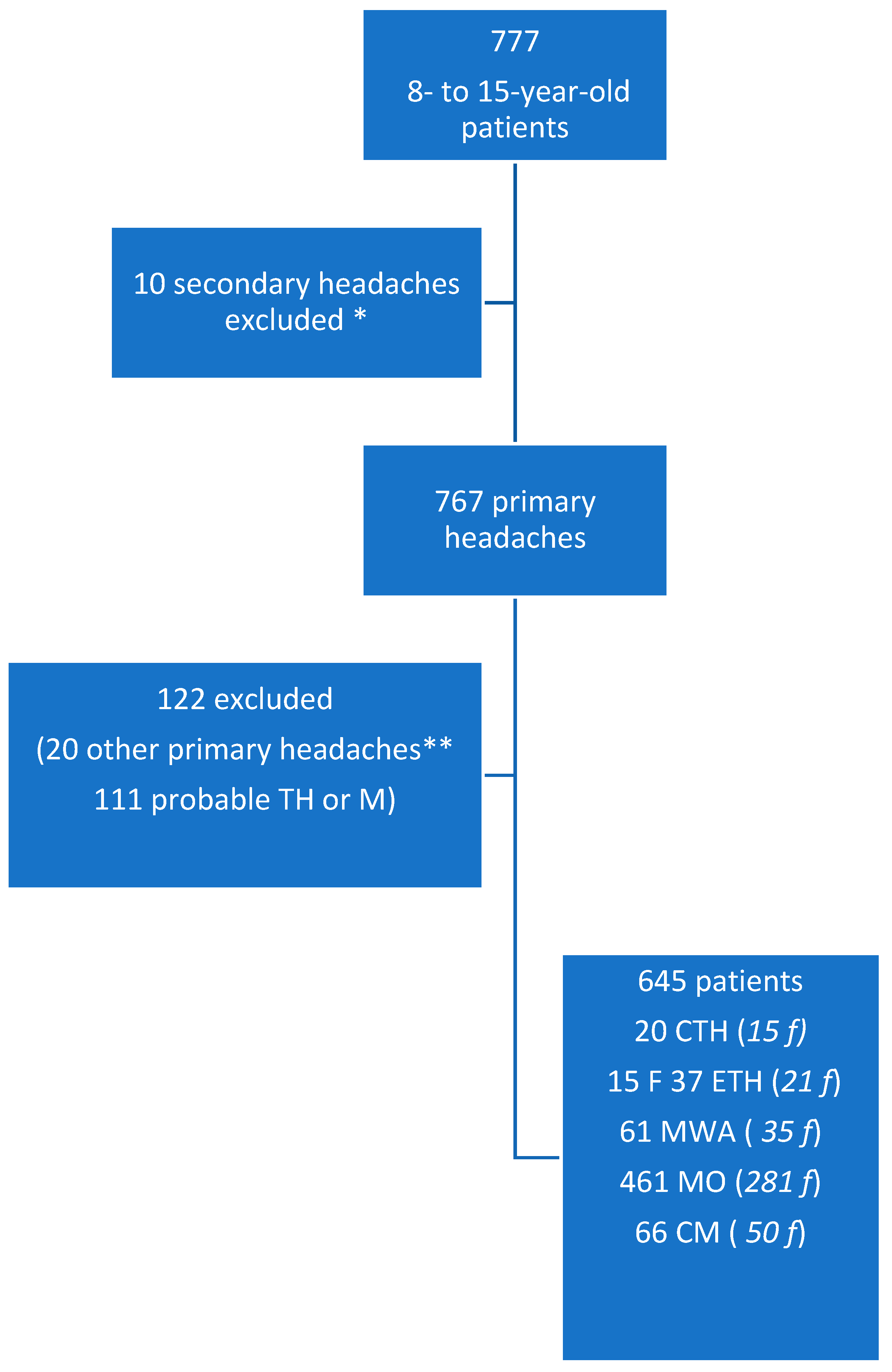

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Frequency of Osmophobia and Demographic Data

3.2. Characteristic of Headache Patients with Osmophobia

3.3. Anxiety, Depression, Pain Catastrophizing and Severity of Allodynia in Migraine Patients with Osmophobia

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches

4.2. Features of Osmophobic Patients in the General Primary Headache Cohort

4.3. Association between Osmophobia and Migraine Disability, Anxiety, Depression and Pain Catastrophizing in a Subset of Migraine Children

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Arafeh, I.; Razak, S.; Sivaraman, B.; Graham, C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winner, P. Pediatric headache. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008, 21, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanchin, G.; Fuccaro, M.; Battistella, P.; Ermani, M.; Mainardi, F.; Maggioni, F. A lost track in ICHD 3 beta: A comprehensive review on osmophobia. Cephalalgia 2016, 38, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, A.A.O.; Medeiros, F.L.; Rocha-Filho, P.A.S. Osmophobia and Odor-Triggered Headaches in Children and Adolescents: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Importance in the Diagnosis of Migraine. Headache 2020, 60, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaro, F.; Maggioni, F.; Mampreso, E.; Zanchin, G. Osmophobia in secondary headaches. In Proceedings of the 13th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies, Florence, Italy, 12–15 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, D.; Zotto, L.D.; Perissinotto, E.; Gallo, L.; Gatta, M.; Balottin, U.; Mazzotta, G.; Moscato, D.; Raieli, V.; Rossi, L.; et al. Osmophobia in migraine classification: A multicentre study in juvenile patients. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, D.; Toldo, I.; Zotto, L.D.; Perissinotto, E.; Sartori, S.; Gatta, M.; Balottin, U.; Mazzotta, G.; Moscato, D.; Raieli, V.; et al. Osmophobia as an early marker of migraine: A follow-up study in juvenile patients. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, L. Osmophobia and Taste Abnormality in Migraineurs: A Tertiary Care Study. Headache 2004, 44, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raieli, V.; Pandolfi, E.; La Vecchia, M.; Puma, D.; Calò, A.; Celauro, A.; Ragusa, D. The prevalence of allodynia, osmophobia and red ear syndrome in the juvenile headache: Preliminary data. J. Headache Pain 2005, 6, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Tommaso, M.; Sciruicchio, V.; Delussi, M.; Vecchio, E.; Goffredo, M.; Simeone, M.; Barbaro, M.G.F. Symptoms of central sensitization and comorbidity for juvenile fibromyalgia in childhood migraine: An observational study in a tertiary headache center. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommaso, M.; Trotta, G.; Vecchio, E.; Ricci, K.; Siugzdaite, R.; Stramaglia, S. Brain networking analysis in migraine with and without aura. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delussi, M.; Laporta, A.; Fraccalvieri, I.; de Tommaso, M. Osmophobia in primary headache patients: Associated symptoms and response to preventive treatments. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemark, M.; Olesen, J. Pericranial Tenderness in Tension Headache: A Blind, Controlled Study. Cephalalgia 1987, 7, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornoe, B.; Andersen, L.L.; Skotte, J.H.; Jensen, R.; Gard, G.; Skov, L.; Hallström, I.K. Reduced neck-shoulder muscle strength and aerobic power together with increased pericranial tenderness are associated with tension-type headache in girls: A case-control study. Cephalalgia 2013, 34, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, D.; Grazzi, L.; Usai, S.; Andrasik, F.; Leone, M.; Rigamonti, A.; Bussone, G. Use of the Migraine Disability Assessment Questionnaire in Children and Adolescents with Headache: An Italian Pilot Study. Headache 2003, 43, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D.; Powers, S.W.; Vockell, A.-L.B.; LeCates, S.; Kabbouche, M.; Maynard, M.K. PedMIDAS: Development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology 2001, 57, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetti, C.; Sannio Fancello, G. Scale Psichiatriche di Autosomministrazione per Fanciulli e Adolescenti (SAFA) [Psychiatric Self Administration Scales for Youths and Adolescents (SAFA)]; Giunti O.S.: Firenze, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pielech, M.; Ryan, M.; Logan, D.; Kaczynski, K.; White, M.T.; Simons, L.E. Pain catastrophizing in children with chronic pain and their parents: Proposed clinical reference points and reexamination of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale measure. Pain 2014, 155, 2360–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommaso, M.; Delussi, M.; Vecchio, E.; Sciruicchio, V.; Invitto, S.; Livrea, P. Sleep features and central sensitization symptoms in primary headache patients. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommaso, M.; Sciruicchio, V.; Ricci, K.; Montemurno, A.; Gentile, F.; Vecchio, E.; Barbaro, M.G.F.; Simeoni, M.; Goffredo, M.; Livrea, P. Laser-evoked potential habituation and central sensitization symptoms in childhood migraine. Cephalalgia 2015, 36, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Bigal, M.E.; Ashina, S.; Burstein, R.; Silberstein, S.; Reed, M.L.; Ma, D.S.; Stewart, W.F.; American Migraine Prevalence Prevention Advisory Group. Cutaneous allodynia in the migraine population. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corletto, E.; Zotto, L.D.; Resos, A.; Tripoli, E.; Zanchin, G.; Bulfoni, C.; Battistella, P. Osmophobia in Juvenile Primary Headaches. Cephalalgia 2008, 28, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasco, V.; Grasso, G.; Versace, A.; Castagno, E.; Ricceri, F.; Urbino, A.; Pagliero, R. Epidemiological and clinical features of migraine in the pediatric population of Northern Italy. Cephalalgia 2015, 36, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, F.; Lucchesi, C.; Ulivi, M.; Cafalli, M.; Vedovello, M.; Vergallo, A.; Del Prete, E.; Nuti, A.; Bonuccelli, U.; Gori, S. Clinical features associated with ictal osmophobia in migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 36, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Fuh, J.-L.; Chen, S.-P.; Wu, J.-C.; Wang, S.-J. Clinical correlates and diagnostic utility of osmophobia in migraine. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Filho, P.A.S.; Marques, K.S.; Torres, R.C.S.; Leal, K.N.R. Osmophobia and Headaches in Primary Care: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Importance in Diagnosing Migraine. Headache 2015, 55, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tommaso, M.; Sciruicchio, V. Migraine and Central Sensitization: Clinical Features, Main Comorbidities and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2016, 12, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tommaso, M.; Ambrosini, A.; Brighina, F.; Coppola, G.; Perrotta, A.; Pierelli, F.; Sandrini, G.; Valeriani, M.; Marinazzo, D.; Stramaglia, S.; et al. Altered processing of sensory stimuli in patients with migraine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou, A.P.; Edvinsson, L. Mechanisms of migraine as a chronic evolutive condition. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosignoli, C.; Ornello, R.; Onofri, A.; Caponnetto, V.; Grazzi, L.; Raggi, A.; Leonardi, M.; Sacco, S. Applying a biopsychosocial model to migraine: Rationale and clinical implications. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsook, D.; Edwards, R.; Elman, I.; Becerra, L.; Levine, J. Pain and analgesia: The value of salience circuits. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 104, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, M.; Aurora, S.; Heinricher, M. Beyond Neurovascular: Migraine as a Dysfunctional Neurolimbic Pain Network. Headache 2012, 52, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, K.L.; Wager, T.D.; Taylor, S.F.; Liberzon, I. Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Human Emotions. CNS Spectrums 2004, 9, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciruicchio, V.; Simeone, M.; Barbaro, M.G.F.; Tanzi, R.C.; Delussi, M.; Libro, G.; D’Agnano, D.; Basiliana, R.; De Tommaso, M. Pain Catastrophizing in Childhood Migraine: An Observational Study in a Tertiary Headache Center. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Filho, P.A.S.; Gherpelli, J.L.D. Premonitory and Accompanying Symptoms in Childhood Migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CTH | ETH | MWA | CM | MO | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | N° | % | ||||

| Osmophobia | No | 15 | 75 | 36 | 97.30 | 37 | 60.70 | 42 | 63.60 | 325 | 70.50 | 459 | 71.20 |

| Yes | 5 | 25 | 1 | 2.70 | 24 | 39.30 | 24 | 36.40 | 136 | 29.50 | 186 | 28.80 |

| TTS | NRS | Duration ** | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTH | ETH | MWA | CM | MO | CTH | ETH | MWA | CM | MO | CTH | ETH | MWA | CM | MO | |

| Osm no | 5.00 (1.02) | 2.37 (0.73) | 1.65 (0.97) | 3.50 (0.74) | 2.70 (0.29) | 6.17 (0.74) | 3.91 (0.53) | 6.95 (0.70) | 6.88 (054) | 6.83 (0.21) | 2.22 (0.53) | 2.17 (0.45) | 2.50 (0.6) | 3.29 (0.46) | 3.08 (0.18) |

| Osm yes | 4.00 (4.34) | . | 4.08 (1.25) | 4.83 (1.25) | 2.67 (0.53) | 9.00 (3.12) | . | 8.17 (0.9) | 5.17 (0.9) | 7.15 (0.38) | 9.00 (2.67) | . | 2.92 (0.77) | 4.42 (0.77) | 4.26 (0.33) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sciruicchio, V.; D’Agnano, D.; Clemente, L.; Rutigliano, A.; Laporta, A.; de Tommaso, M. Clinical Correlates of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches: An Observational Study in Child Cohorts. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082939

Sciruicchio V, D’Agnano D, Clemente L, Rutigliano A, Laporta A, de Tommaso M. Clinical Correlates of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches: An Observational Study in Child Cohorts. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(8):2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082939

Chicago/Turabian StyleSciruicchio, Vittorio, Daniela D’Agnano, Livio Clemente, Alessandra Rutigliano, Anna Laporta, and Marina de Tommaso. 2023. "Clinical Correlates of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches: An Observational Study in Child Cohorts" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 8: 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082939

APA StyleSciruicchio, V., D’Agnano, D., Clemente, L., Rutigliano, A., Laporta, A., & de Tommaso, M. (2023). Clinical Correlates of Osmophobia in Primary Headaches: An Observational Study in Child Cohorts. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(8), 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082939