Changes in Revolving-Door Mental Health Hospitalizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 5-Year Chart Review Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures and Participants

2.2. Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

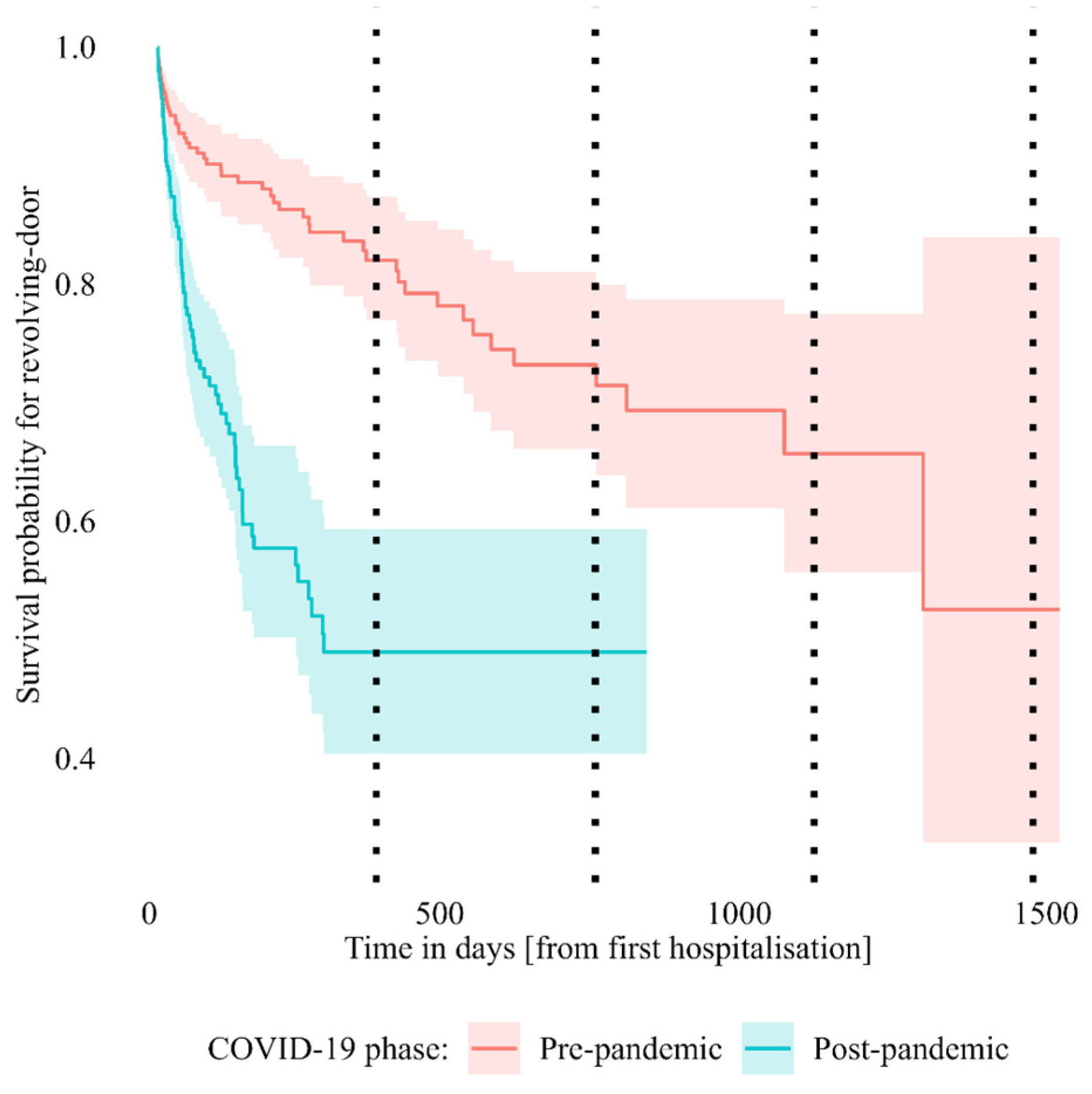

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Sagona, M.; Landi, G.; Martire, L.; Piemonte, C.; Del Giovane, C. The revolving door phenomenon in an Italian acute psychiatric ward: A 5-year retrospective analysis of the potential risk factors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlino, M.; Calento, A.; Schiavone, V.; Santone, G.; Picardi, A.; de Girolamo, G.; for the PROGRES-Acute Group. Use of psychiatric inpatient services by heavy users: Findings from a national survey in Italy. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golay, P.; Morandi, S.; Conus, P.; Bonsack, C. Identifying patterns in psychiatric hospital stays with statistical methods: Towards a typology of post-deinstitutionalization hospitalization trajectories. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhig, M.; Gunasekara, I.; Patterson, S. Understanding readmission to psychiatric hospital in Australia from the service users’ perspective: A qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Orta, I.; Herrmann, F.R.; Giannakopoulos, P. Determinants of revolving door in an acute psychiatric ward for prison inmates. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 626773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Similä, N.; Hakko, H.; Riipinen, P.; Riala, K. Gender specific characteristics of revolving door adolescents in acute psychiatric inpatient care. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2018, 49, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, L.; Kutz, A.; Haubitz, S.; Mueller, B.; Perrig-Chiello, P.; Schuetz, P. Psychological distress in medical patients 30 days following an emergency department admission: Results from a prospective, observational study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2016, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F.; Carr, M.J.; Mok, P.L.H.; Antonsen, S.; Pedersen, C.B.; Appleby, L.; Fazel, S.; Shaw, J.; Webb, R.T. Multiple adverse outcomes following first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care: A national cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haywood, T.W.; Kravitz, H.M.; Grossman, L.S.; Cavanaugh, J.L.; Davis, J.M.; Lewis, D.A. Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledoux, Y.; Minner, P. Occasional and frequent repeaters in a psychiatric emergency room. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadish, W.; Lurigio, A.; Lewis, D. After Deinstitutionalization—The present and future of mental-health long-term care policy. J. Soc. Issues 1989, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Borelli, W.V.; Benzano, D.; Schuch, J.B.; Moura, H.F.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P.; Scherer, J.N.; von Diemen, L. The next pandemic: Impact of COVID-19 in mental healthcare assistance in a nationwide epidemiological study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2021, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoletto, R.; Di Gennaro, G.; Antolini, G.; Mondini, F.; Passarella, L.; Rizzo, V.; Silvestri, M.; Darra, F.; Zoccante, L.; Colizzi, M. Sociodemographic and clinical changes in pediatric in-patient admissions for mental health emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic: March 2020 to June 2021. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, M.; Rucci, P.; Amendola, D.; Bonizzoni, M.; Cerveri, G.; Colli, C.; Dragogna, F.; Ducci, G.; Elmo, M.; Ghio, L.; et al. Emergency psychiatric consultations during and after the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. A multicentre study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 697058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Jones, P.B.; Underwood, B.R.; Moore, A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Banerjee, S.; Osimo, E.F.; Deakin, J.B.; Hatfield, C.F.; Thompson, F.J.; et al. The early impact of COVID-19 on mental health and community physical health services and their patients’ mortality in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, UK. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 131, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S.; Stevens, R.F. Subgroups of frequent users of an inpatient mental health program at a community hospital in Canada. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999, 50, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Li, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Utilization of Inpatient Mental Health Services in Shanghai, China. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghi, M.; Ferrari, S.; Brandolini, R.; Casolaro, I.; Balestrieri, M.; Colli, C.; Fraticelli, C.; Di Lorenzo, R.; De Paoli, G.; Nicotra, A.; et al. Effects of lockdown on emergency room admissions for psychiatric evaluation: An observational study from 4 centres in Italy. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2022, 26, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | Without RD | With RD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 49.5% | 45.8% | |

| Male | 50.5% | 54.2% | ||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 91.8% | 86.4% | |

| Asian | 3.9% | 5.1% | ||

| Afro | 2.7% | 5.1% | ||

| Hispanic | 1.6% | 3.4% | ||

| Age at first hospitalisation | 44.8 ± 15.70 | 37.3 ± 14.04 | * | |

| Age-group | <30 years-old | 21.8% | 40.7% | * |

| 30–40 years-old | 18.8% | 18.6% | ||

| 41–50 years-old | 22.0% | 23.7% | ||

| >50 years-old | 37.4% | 16.9% | ||

| Number of hospitalisations | 1.3 ± 0.58 | 5.5 ± 2.71 | * | |

| Mean duration of hospitalisation in hours | 207.0 ± 403.79 | 201.0 ± 159.43 | ||

| Diagnosis | Psychotic disorder, non-affective | 30.4% | 49.2% | * |

| Affective disorder | 32.7% | 44.1% | ||

| Non-psychotic mental disorder | 25.6% | 35.6% | ||

| Personality disorder | 5.8% | 33.9% | * | |

| Substance use disorder | 7.4% | 15.3% | * | |

| Intellectual disability | 3.8% | 20.3% | * | |

| Physiological condition | 2.1% | 5.1% | ||

| Other diagnosis | 3.2% | 13.6% | * | |

| Referral source | Mental Health Service | 84.2% | 91.5% | |

| Addiction Service | 4.8% | 10.2% | ||

| Disability Service | 0.7% | 1.7% | ||

| Child/Adolescent Mental Health Service | 0.6% | 1.7% | ||

| Private Service | 4.9% | 3.4% | ||

| Unknown Service | 8.7% | 3.4% | ||

| Any compulsory | 14.1% | 27.1% | * | |

| Any absconding | 3.2% | 28.8% | * | |

| Phase of CODID-19 | Only pre-pandemic | 47.1% | 28.8% | * |

| Both pre- & post-pandemic | 7.6% | 45.8% | ||

| Only post-pandemic | 45.3% | 25.4% | ||

| Number of RD | - | 2.7 ± 2.48 | - | |

| Any RD | 0.0% | 100.0% | - | |

| Predictor | OR [95% CI] | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Phase of COVID-19 (post-pandemic = 1) | 2.155 [1.403, 3.312] | z = +3.504, p < 0.001 * |

| Relations with the service (new patient = 1) | 0.146 [0.076, 0.281] | z = −5.766, p < 0.001 * |

| Kind of hospitalisation (compulsory = 1) | 0.939 [0.462, 1.908] | z = −0.175, p = 0.861 |

| Psychotic disorder, non-affective (diagnosis = 1) | 0.437 [0.153, 1.251] | z = −1.542, p = 0.123 |

| Affective disorder (diagnosis = 1) | 0.417 [0.143, 1.212] | z = −1.606, p = 0.108 |

| Non-psychotic mental disorder (diagnosis = 1) | 0.478 [0.164, 1.393] | z = −1.352, p = 0.176 |

| Personality disorder (diagnosis = 1) | 1.439 [0.505, 4.100] | z = +0.680, p = 0.496 |

| Substance abuse disorder (diagnosis = 1) | 0.570 [0.165, 1.971] | z = −0.888, p = 0.374 |

| Intellectual disability (diagnosis = 1) | 0.289 [0.082, 1.022] | z = −1.926, p = 0.054 |

| Physiological condition (diagnosis = 1) | 0.555 [0.055, 5.567] | z = −0.500, p = 0.617 |

| Sex (male = 1) | 1.358 [0.793, 2.326] | z = +1.115, p = 0.265 |

| Age at the hospitalisation (standardized) | 0.802 [0.596, 1.079] | z = −1.459, p = 0.144 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Napoli, G.; Garzitto, M.; Magliulo, V.; Carnemolla, R.; Anzallo, C.; Balestrieri, M.; Colizzi, M. Changes in Revolving-Door Mental Health Hospitalizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 5-Year Chart Review Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072681

Napoli G, Garzitto M, Magliulo V, Carnemolla R, Anzallo C, Balestrieri M, Colizzi M. Changes in Revolving-Door Mental Health Hospitalizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 5-Year Chart Review Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(7):2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072681

Chicago/Turabian StyleNapoli, Giovanni, Marco Garzitto, Vincenzo Magliulo, Rossana Carnemolla, Calogero Anzallo, Matteo Balestrieri, and Marco Colizzi. 2023. "Changes in Revolving-Door Mental Health Hospitalizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 5-Year Chart Review Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 7: 2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072681

APA StyleNapoli, G., Garzitto, M., Magliulo, V., Carnemolla, R., Anzallo, C., Balestrieri, M., & Colizzi, M. (2023). Changes in Revolving-Door Mental Health Hospitalizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 5-Year Chart Review Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(7), 2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072681