Brain Hypothermia Therapy and Targeted Temperature Management for Acute Encephalopathy in Children: Status and Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Therapeutic Hypothermia

3. Brief History of Therapeutic Hypothermia

4. Pathogenesis of Neuronal Damage in Hypoxic and Hypoperfused Brain Tissue

5. Mechanisms of Hypothermia

6. Evidence of Therapeutic Hypothermia in Acute Encephalopathy

7. Gaps and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slooter, A.J.C.; Otte, W.M.; Devlin, J.W.; Arora, R.C.; Bleck, T.P.; Claassen, J.; Duprey, M.S.; Ely, E.W.; Kaplan, P.W.; Latronico, N.; et al. Updated nomenclature of delirium and acute encephalopathy: Statement of ten societies. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, M.; Ichiyama, T.; Imataka, G.; Okumura, A.; Goto, T.; Sakuma, H.; Takanashi, J.I.; Murayama, K.; Yamagata, T.; Yamanouchi, H.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute encephalopathy in childhood. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Saitoh, M.; Oka, A.; Okumura, A.; Kubota, M.; Saito, Y.; Takanashi, J.; Hirose, S.; Yamagata, T.; Yamanouchi, H.; et al. Epidemiology of acute encephalopathy in Japan, with emphasis on the association of viruses and syndromes. Brain Dev. 2012, 34, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, M.; Shibata, A.; Hoshino, A.; Maegaki, Y.; Yamanouchi, H.; Takanashi, J.I.; Yamagata, T.; Sakuma, H.; Okumura, A.; Nagase, H.; et al. Epidemiological changes of acute encephalopathy in Japan based on national surveillance for 2014–2017. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imataka, G.; Kuwashima, S.; Yoshihara, S. A Comprehensive Review of Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.E.; Asfour, A.; Sewell, T.B.; Hooe, B.; Pryce, P.; Earley, C.; Shen, M.Y.; Kerner-Rossi, M.; Thakur, K.T.; Vargas, W.S.; et al. Neurological issues in children with COVID-19. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 743, 135567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, V.; Mohseni-Bod, H.; Drake, J. Management of raised intracranial pressure in children with traumatic brain injury. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Sakai, T.; Okumura, A.; Akaboshi, S.; Fukuda, M.; Haginoya, K.; Hamano, S.; Hirano, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Kubota, M.; et al. Manifestations and characteristics of congenital adrenal hyperplasia-associated encephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2016, 38, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaworski, A.; Alobaidi, R.; Liu, N.; Mailo, J.; Kassiri, J. Pediatric encephalopathy and complex febrile seizures. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 61, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pinto, T.; Luna-Rodríguez, A.; Moreno-Estébanez, A.; Agirre-Beitia, G.; Rodríguez-Antigüedad, A.; Ruiz-Lopez, M. Emergency room neurology in times of COVID-19: Malignant ischaemic stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, e35–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.; Chaurasia, B.; Fiorindi, A.; Umana, G.E.; Lu, B.; Montemurro, N. Ischemic Stroke and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The Bidirectional Pathology and Risk Morbidities. Neurol. Int. 2022, 14, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, A.M.; Bezerra, A.L.M.S.; Felix, E.B.G.; Júnior, J.C.S.; Pinto, N.B.; Neto, M.L.R.; de Aguiar Rocha Martin, A.L. COVID-19’s Clinical-Pathological Evidence in Relation to Its Repercussion on the Central and Peripheral Nervous System. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1353, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maury, A.; Lyoubi, A.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; de Broucker, T.; Meppiel, E. Neurological manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses: A narrative review for clinicians. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 177, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.K.; Ojha, S.; Jha, S.K.; Dureja, H.; Singh, S.K.; Shukla, S.D.; Chellappan, D.K.; Gupta, G.; Bhardwaj, S.; Kumar, N.; et al. Evidence of Coronavirus (CoV) Pathogenesis and Emerging Pathogen SARS-CoV-2 in the Nervous System: A Review on Neurological Impairments and Manifestations. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 2192–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudubray, J.M.; Garcia-Cazorla, A. An overview of inborn errors of metabolism affecting the brain: From neurodevelopment to neurodegenerative disorders. Dial. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, A.; Mizuguchi, M.; Kidokoro, H.; Tanaka, M.; Abe, S.; Hosoya, M.; Aiba, H.; Maegaki, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanabe, T.; et al. Outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in relation to treatment with corticosteroids and gammaglobulin. Brain Dev. 2009, 31, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esen, F.; Ozcan, P.E.; Tuzun, E.; Boone, M.D. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immunoglobulin in septic encephalopathy. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 29, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Okumura, A.; Kurahashi, H.; Numoto, S.; Abe, S.; Ikeno, M.; Shimizu, T. Norovirus-associated Encephalitis/Encephalopathy Collaborative Study investigators A nationwide survey of norovirus-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy in Japan. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanuma, N.; Miyata, R.; Nakajima, K.; Okumura, A.; Kubota, M.; Hamano, S.; Hayashi, M. Changes in cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in human herpesvirus-6-associated acute encephalopathy/febrile seizures. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 564091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwer, S.; Gatakaa, H.; Mwai, L.; Idro, R.; Newton, C.R. The role for osmotic agents in children with acute encephalopathies: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Fujita, K.; Maruyama, A.; Nagase, H. Targeted temperature management of acute encephalopathy without AST elevation. Brain Dev. 2015, 37, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Fujita, K.; Saji, Y.; Maruyama, A.; Nagase, H. Induced hypothermia/normothermia with general anesthesia prevents neurological damage in febrile refractory status epilepticus in children. No Hattatsu. 2011, 43, 459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Imataka, G.; Arisaka, O. Brain hypothermia therapy for childhood acute encephalopathy based on clinical evidence. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imataka, G.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kano, Y.; Ogino, K.; Tsuchioka, T.; Ohnishi, T.; Kaji, Y.; Wake, K.; Ichikawa, G.; Suzumura, H.; et al. Treatment with mild brain hypothermia for cardiopulmonary resuscitation after myoclonic seizures in infant with Robertsonian type of trisomy 13. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 19, 2852–2855. [Google Scholar]

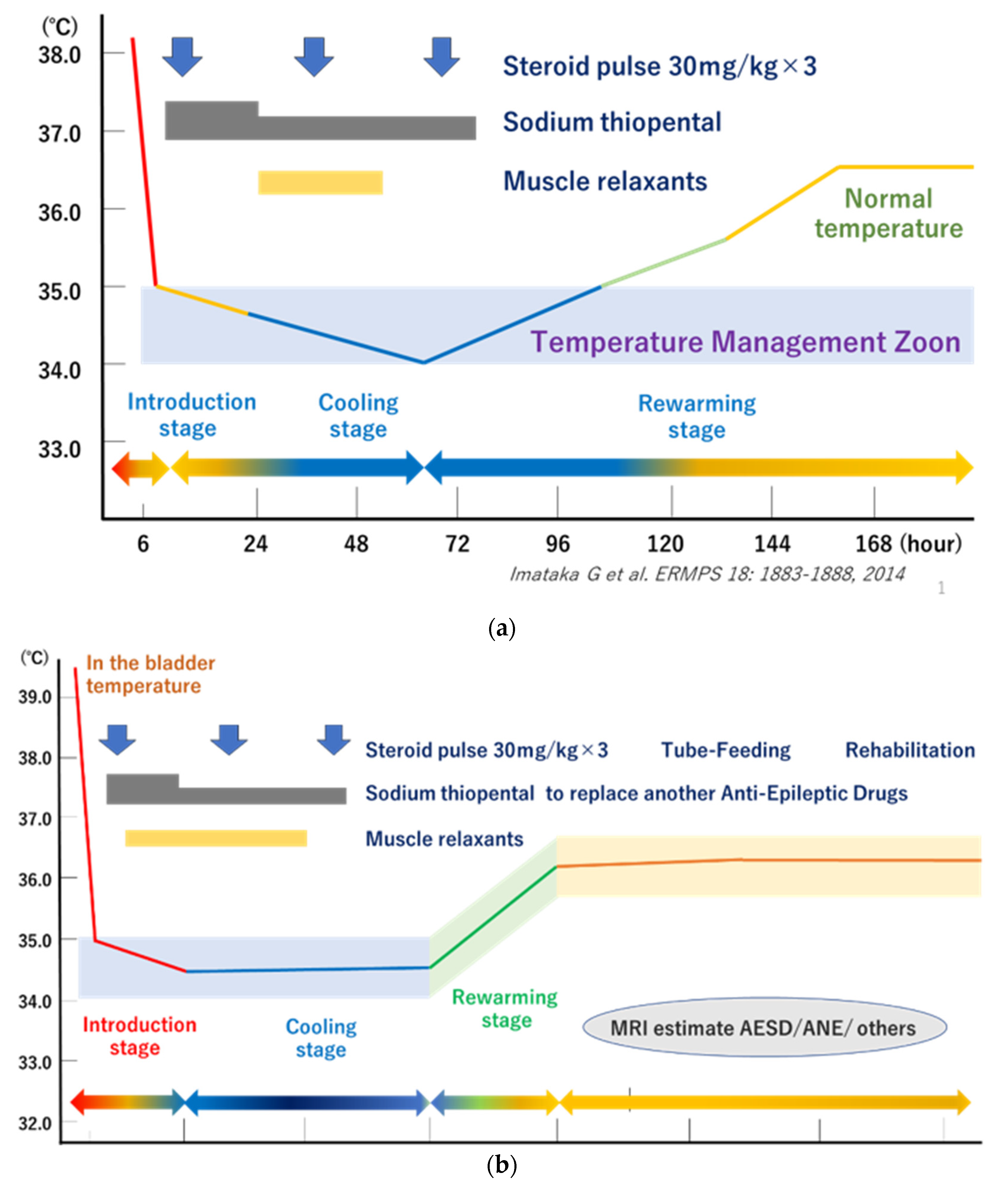

- Imataka, G.; Wake, K.; Yamanouchi, H.; Ono, K.; Arisaka, O. Brain hypothermia therapy for status epilepticus in childhood. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 18, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshide, M.; Yasudo, H.; Inoue, H.; Matsushige, T.; Sakakibara, A.; Nawata, Y.; Hidaka, I.; Kobayashi, H.; Kohno, F.; Ichiyama, T.; et al. Efficacy of hypothermia therapy in patients with acute encephalopathy with biphasic seizures and late reduced diffusion. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

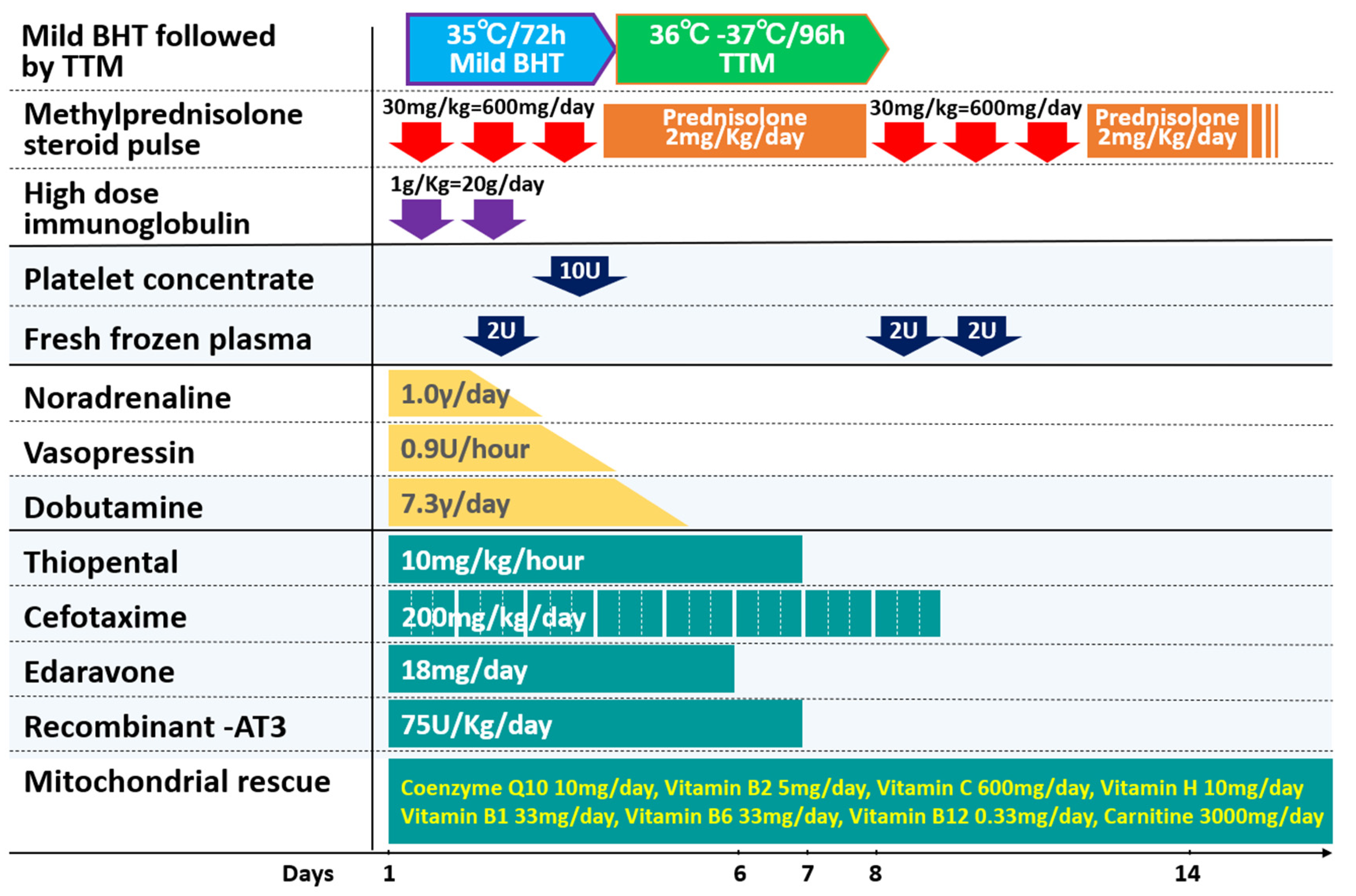

- Fujita, Y.; Imataka, G.; Kikuchi, J.; Yoshihara, S. Successful mild brain hypothermia therapy followed by targeted temperature management for pediatric hemorrhagic shock and encephalopathy syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 25, 3002–3006. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, S.A.; Gray, T.W.; Buist, M.D.; Jones, B.M.; Silvester, W.; Gutteridge, G.; Smith, K. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Tyson, J.E.; McDonald, S.A.; Donovan, E.F.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Poole, W.K.; Wright, L.L.; Higgins, R.D.; et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Kumar, V.; Shankaran, S.; Thayyil, S. Rise and fall of therapeutic hypothermia in low-resource settings: Lessons from the HELIX trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatovskaia, L.V.; Wartenberg, K.E.; Freeman, W.D. Therapeutic hypothermia for neuroprotection: History, mechanisms, risks, and clinical applications. Neurohospitalist 2014, 4, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, C.; Nakagiri, K.; Yamashita, T.; Matsuda, H.; Wakiyama, H.; Yoshida, M.; Ataka, K.; Okada, M. Mild hypothermia for temporary brain ischemia during cardiopulmonary support systems: Report of three cases. Surg. Today 1999, 29, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayas, Z.Ö.; Uncu, G.; Adapınar, D.Ö. Disorders of Consciousness—A Review of Important Issues [internet]. In Hypoxic Brain Injury; Dogan, K.H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/69521 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Kleuskens, D.G.; Gonçalves Costa, F.; Annink, K.V.; van den Hoogen, A.; Alderliesten, T.; Groenendaal, F.; Benders, M.J.N.; Dudink, J. Pathophysiology of cerebral hyperperfusion in term neonates With hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A systematic review for future research. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 631258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Fan, B.; Li, G.Y. Neuroprotection by therapeutic hypothermia. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imataka, G.; Hirato, J.; Nakazato, Y.; Yamanouchi, H. Expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit R1 in the developing human hippocampus. J. Child. Neurol. 2006, 21, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, A.J.; Laptook, A.R.; Robertson, N.J.; Barks, J.D.; Thoresen, M.; Wassink, G.; Bennet, L. Therapeutic hypothermia translates from ancient history in to practice. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presciutti, A.; Perman, S.M. The evolution of hypothermia for neuroprotection after cardiac arrest: A history in the making. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1507, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legriel, S. Hypothermia as a treatment in status epilepticus: A narrative review. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 101, 106298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.J.; Hsia, S.H.; Chiang, M.C.; Lin, K.L. Clinical application of target temperature management in children with acute encephalopathy-A practical review. Biomed. J. 2020, 43, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.E.; Berg, M.; Hunt, R.; Tarnow-Mordi, W.O.; Inder, T.E.; Davis, P.G. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 1, CD003311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptook, A.R.; Shankaran, S.; Tyson, J.E.; Munoz, B.; Bell, E.F.; Goldberg, R.N.; Parikh, N.A.; Ambalavanan, N.; Pedroza, C.; Pappas, A.; et al. Effect of therapeutic hypothermia initiated after 6 hours of age on death or disability among newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 1550–1560, Published correction appears in JAMA 2018, 319, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, C.H.; Hersh, A.R.; Sargent, J.A.; Caughey, A.B. Therapeutic hypothermia in severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2022, 35, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, K.; Kawano, G.; Suda, M.; Yokochi, T.; Yae, Y.; Imagi, T.; Akita, Y.; Ohbu, K.; Matsuishi, T. Determinants of outcomes for acute encephalopathy with reduced subcortical diffusion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Imataka, G.; Sakuma, H.; Takanashi, J.I.; Yoshihara, S. Multiple encephalopathy syndrome: A case of a novel radiological subtype of acute encephalopathy in childhood. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 26, 5729–5735. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, S.; Kashiwagi, M.; Tanabe, T.; Oba, C.; Shigehara, S.; Yamazaki, S.; Ashida, A.; Sirasu, A.; Inoue, K.; Okasora, K.; et al. Targeted temperature management for acute encephalopathy in a Japanese secondary emergency medical care hospital. Brain Dev. 2016, 38, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilliams, K.; Rosen, M.; Buttram, S.; Zempel, J.; Pineda, J.; Miller, B.; Shoykhet, M. Hypothermia for pediatric refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2013, 54, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, G.; Iwata, O.; Iwata, S.; Kawano, K.; Obu, K.; Kuki, I.; Rinka, H.; Shiomi, M.; Yamanouchi, H.; Kakuma, T.; et al. Research Network for Acute Encephalopathy in Childhood. Determinants of outcomes following acute child encephalopathy and encephalitis: Pivotal effect of early and delayed cooling. Arch. Dis. Child. 2011, 96, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, S. Efficacy of different treatment times of mild cerebral hypothermia on oxidative factors and neuroprotective effects in neonatal patients with moderate/severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520943770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Wyatt, J.S.; Azzopardi, D.; Ballard, R.; Edwards, A.D.; Ferriero, D.M.; Polin, R.A.; Robertson, C.M.; Thoresen, M.; Whitelaw, A.; et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: Multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2005, 365, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayyil, S.; Pant, S.; Montaldo, P.; Shukla, D.; Oliveira, V.; Ivain, P.; Bassett, P.; Swamy, R.; Mendoza, J.; Moreno-Morales, M.; et al. Hypothermia for moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy in low-income and middle-income countries (HELIX): A randomised controlled trial in India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1273–e1285, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, J.L.; Kaur, N.; Dsouza, J.M. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonatal hypoxic encephalopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 04030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, A.M.; Fang, A.Y.; Bonifacio, S.; Rogers, E.E.; Scheffler, A.; Partridge, J.C.; Xu, D.; Barkovich, A.J.; Ferriero, D.M.; Glass, H.C.; et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging predicts 30-month outcomes after therapeutic hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2021, 238, 94–101.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuguchi, M.; Yamanouchi, H.; Ichiyama, T.; Shiomi, M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2007, 186, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenari, M.A.; Han, H.S. Neuroprotective mechanisms of hypothermia in brain ischaemia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurisu, K.; Yenari, M.A. Therapeutic hypothermia for ischemic stroke; pathophysiology and future promise. Neuropharmacology 2018, 134, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F.C.; Buchheim, K.; Meierkord, H.; Holtkamp, M. Anticonvulsant properties of hypothermia in experimental status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 23, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowski, A.B.; Kanaan, H.; Schmitt, F.C.; Holtkamp, M. Deep hypothermia terminates status epilepticus—An experimental study. Brain Res. 2012, 1446, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BHT | TTM |

|---|---|

| Head cooling alone for neonates Whole-body cooling for infants and children | Whole body mild cooling |

| Lower body temperature by more than 2 °C The target body temperature for BHT is 32 °C to 35 °C | Lower body temperature by 1–2 °C TTM maintains and controls the target body temperature at 36 °C for an extended period of time |

| Generally, ventilator management is required | Ventilator management is not required |

| Higher rewarming process | Relatively less duration of rewarming phase |

| Requires ICU support-intubation and ventilator management. Intravenous fluids, maintenance of blood pressure, and systemic circulatory control are required. | Can be performed in general wards |

| Antiepileptic drugs such as barbiturates and steroid pulse therapy are often used in combination in severe pediatric acute encephalopathy. | For the most severe form of acute encephalopathy in children with high-cytokine type, TTM is not sufficient for management. |

| Reference | Indication | Age (Years) | N | Goal Temp. (°C) | Duration of Hypothermia, Hours | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTM | ||||||

| Guilliams et al. (2013) [47] | Refractory status epilepticus | 5 months–15 years | 5 | 32–35 | 24–120 | No recurrence (100%). One child died. Two patients required PICU care. |

| Nishiyama et al. (2015) [21] | Acute encephalopathy without serum aspartate aminotransferase elevation | 6.9–14.2 years | 57 | 34.5–36 | 72 | Good neurological outcomes (100%). PICU not required |

| Shankaran et al. (2005) [29] | Moderate/severe HIE | Neonates of at least 36 weeks | 102 to HT 106 to control | Esophageal temperature of 33.5 for 72 h | 72 h | Death or moderate or severe disability: 44% with whole-body cooling vs. 62% control. (risk ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.54 to 0.95; p = 0.01) |

| Brain Hypothermia Therapy | ||||||

| Kawano et al. (2011) [48] | Acute child encephalopathy and encephalitis treated at PICUs. | 2–5 years | 43 | 33.5–35 | 48–72 | PCPC outcomes: Early HT (≤12 h): 14/17 (82.4%) versus late HT (>12 h): 2/10 (20%) versus NT: 9/16 (56.3%) |

| Yang et al. (2020) [49] | Moderate/severe HIE with 1-min Apgar score ≤ 3 and 5-min Apgar score ≤ 5 | Neonates < 6 h | 62 to HT group 30 to control group | 28.0–30.0 (head skin Temp.); 34.5 ± 0.5 (body surface skin); 35.5 ± 0.5 (anal temp) | 72 | Hypothermia treatment of 72 h is better than 48 h for improving oxidative conditions, reducing NSE values, and improving neurological behavior |

| Gluckman et al. (2005) [50] | Moderate/severe HIE | Neonates < 6 h | 116 to HT group 118 to control group | Rectal temperature maintained at 34–35 | 72 h | Head cooling had no effect on infants with the most severe aEEG changes (n = 46, 1.8; 0.49–6.4, p = 0.51), but was beneficial to infants with less severe aEEG changes (n = 172, 0.42; 0.22–0.80, p = 0.009). |

| Antiseizure medication treatment for status epilepticus (A) Midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) administered through the nasal cavity or cheek mucosa. (B) Midazolam (0.15 mg/kg) intravenously (i.v.) administered (up to two doses possible). (C) Between ages 0 and 2 years: intravenous phenobarbital; between 15 and 20 mg/kg (10 min i.v.), ≥2 years: phenobarbital or fosphenytoin 22.5 mg/kg (10 min i.v.). If febrile convulsions associated with fever and Dravet syndrome cannot be ruled out, phenobarbital should be used instead of fosphenytoin. (D) Sodium thiopental between 3 and 5 mg/kg (slow i.v.). Brain hypothermia therapy This protocol applies to infants weighing ≥7.5 kg and aged ≥6 months. Introductory period 1. Status epilepticus/acute encephalopathy admission: ICU (request for admission), contact brainwave department or radiology (brain and chest CT). 2. Check vital signs and establish a peripheral line. 3. Establish central venous line: establish double/triple lumen catheter and arterial line. 4. Fluid infusion between 80 and 100 mL/kg/d: under whole-body management, fluid control must not be reduced to more than necessary to maintain blood pressure and cerebral circulation. Blood pressure is evaluated using an arterial pressure monitor. Maintenance fluids comprise the prepared acetic acid and lactic acid. Vitamins are administered. When theophylline is administered, vitamin B6 is measured (light-shielding blood collection tube: administer vitamin B6 for theophylline-related seizures. Take care not to induce cardiac arrest by sudden administration of B6). 5. Manage blood count, electrolytes, blood sugar, albumin, and clotting value. Submit to check ferritin, soluble IL-2R (sIL-2R), β2MG, procalcitonin, immunoglobulin, etc. 6. Mannitol 3–5 mL/kg × 4–6 times/d is administered over 1 h. 7. Harvest spinal fluid (after the first administration of mannitol). Submit to check the general spinal fluid, various cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α), and tau protein. Freeze and store the remaining fluid at −80 °C. 8. If possible, implement MRI (DWI/ADC-map) time-wise. 9. Intratracheal intubation (if difficult, use muscle relaxant or inhalation anesthetic). 10. Artificial ventilation: use pCO2 at 35–40 mmHg (do not over-ventilate). Keep PEEP slightly low considering brain hypertension. Raise head by 10°. If brain hypertension occurs, request placement of intracerebral pressure (ICP) monitor by a neurosurgeon. 11. Steroid pulse therapy: use methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg for >2 h for 3 d, during which heparin or fragmin therapy is continued ≥APTT 1.5. 12. Administer famotidine 0.5 mg/kg twice/day or omeprazole (15 years and older 20 mg twice/day). 13. Brain hypothermia therapy: use the whole-body blanket-cooling method to induce target body temperature (direct intestine or bladder temperature of 34.0 °C–35.0 °C or 35.5 °C) within 6 h of onset. If necessary, cool the head or wash the stomach with normal saline while taking care not to cause electrolyte abnormalities or use chilled fluid infusion. Brain hypothermia is managed in the ICU followed by TTM in the ICU or intensively manageable general ward. TTM of maintaining brain temperature between 36 °C and 37 °C using bladder temperature as an indicator, with a high correlation. 14. Antiseizure medication: use sodium thiopental, 5–10 mg/kg/h (if this cannot be used, consider midazolam, 0.3–0.9 mg/kg/h). 15. Mitochondrial rescue therapy (MRT): use coenzyme Q10 3–5 mg/kg/day, Vitamin B2 5 mg/kg/day, Vitamin C 50 mg/kg/day, Vitamin H 0.5 mg/kg/day, Vitamin B1 10 mg/kg/day, Vitamin B6 20–50 mg/kg/day, Vitamin B12 0.03–0.05 mg/kg/day, Vitamin E 10 mg/kg/day, and Carnitine 50–100 mg/kg/day. The duration of treatment should be determined by the clinical course. It is usually 2 weeks or more. 16. Dexstromethorphan therapy: use 2 mg/kg for 5 days for prevention of biphasic encephalopathy after febrile status convulsive. Start within 6 h of onset of convulsion. 17. Sedation depth should be confirmed by portable electroencephalograph or paperless electroencephalograph (Makin2) as reaching suppression burst within 6 h of beginning therapy. Cooling period 18. Maintain the target temperature for 48 h (or a maximum of 72 h) in the ICU or general ward. Confirm BIS value at suppression burst (aim for 40 or below) and adjust the sodium thiopental dose administered based on BIS value as appropriate. Cases achieving positive sedation depth should have their sodium thiopental dose reduced prior to rewarming at BIS values between 60 and 70, and at a body temperature of 35.0 °C. [Caution] If spikes remain with suppression bursts, consider complete suppression (pupils will constrict to mydriasis, and response to light is lost with a BIS value of 20 or lower). 19. Use INVOSTM at an appropriate time to check oxygen saturation at the left and right front scalp and to evaluate brain circulation. 20. Blood pressure maintenance: use an appropriate dose of dopamine hydrochloride (5 µg/kg/min = 0.3 mg/kg/h = 0.015 mL/kg/h) and manage electrolyte abnormalities and blood glucose. Heart rate will fall to bradycardia with falling body temperature. 21. Administer antibacterial as appropriate. In applicable conditions, cerebroprotective edaravone, sivelestat Na as a neutrophil elastase inhibitor, and acyclovir are administered. Rewarming period 22. Rewarming is performed at a rate of 0.5 °C/12 h. Care should be taken to avoid pneumonia in line with increased sputum secretions. Aim to remove the patient from artificial respiration between days 5 and 7. For cases in which laryngitis is likely, intravenous dexamethasone or epinephrine should be administered prior to the removal of the tube. 23. For cases in which critical complications are envisaged, TRH therapy should be initiated at an early stage. 24 Include rehabilitation, aiming to discharge the patient one month after onset. 25. Prior to discharge, evaluate brain waves, implement neuroradiological images or nuclear medicine tests, and assess development. Where necessary, antiseizure mediation should be periodically administered for preventative purposes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imataka, G.; Fujita, Y.; Kikuchi, J.; Wake, K.; Ono, K.; Yoshihara, S. Brain Hypothermia Therapy and Targeted Temperature Management for Acute Encephalopathy in Children: Status and Prospects. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062095

Imataka G, Fujita Y, Kikuchi J, Wake K, Ono K, Yoshihara S. Brain Hypothermia Therapy and Targeted Temperature Management for Acute Encephalopathy in Children: Status and Prospects. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(6):2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062095

Chicago/Turabian StyleImataka, George, Yuji Fujita, Jin Kikuchi, Koji Wake, Kazuyuki Ono, and Shigemi Yoshihara. 2023. "Brain Hypothermia Therapy and Targeted Temperature Management for Acute Encephalopathy in Children: Status and Prospects" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 6: 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062095

APA StyleImataka, G., Fujita, Y., Kikuchi, J., Wake, K., Ono, K., & Yoshihara, S. (2023). Brain Hypothermia Therapy and Targeted Temperature Management for Acute Encephalopathy in Children: Status and Prospects. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(6), 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062095