Non-Surgical Management of the Gingival Smile with Botulinum Toxin A—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Registration

2.2. Search of the Literature Process

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

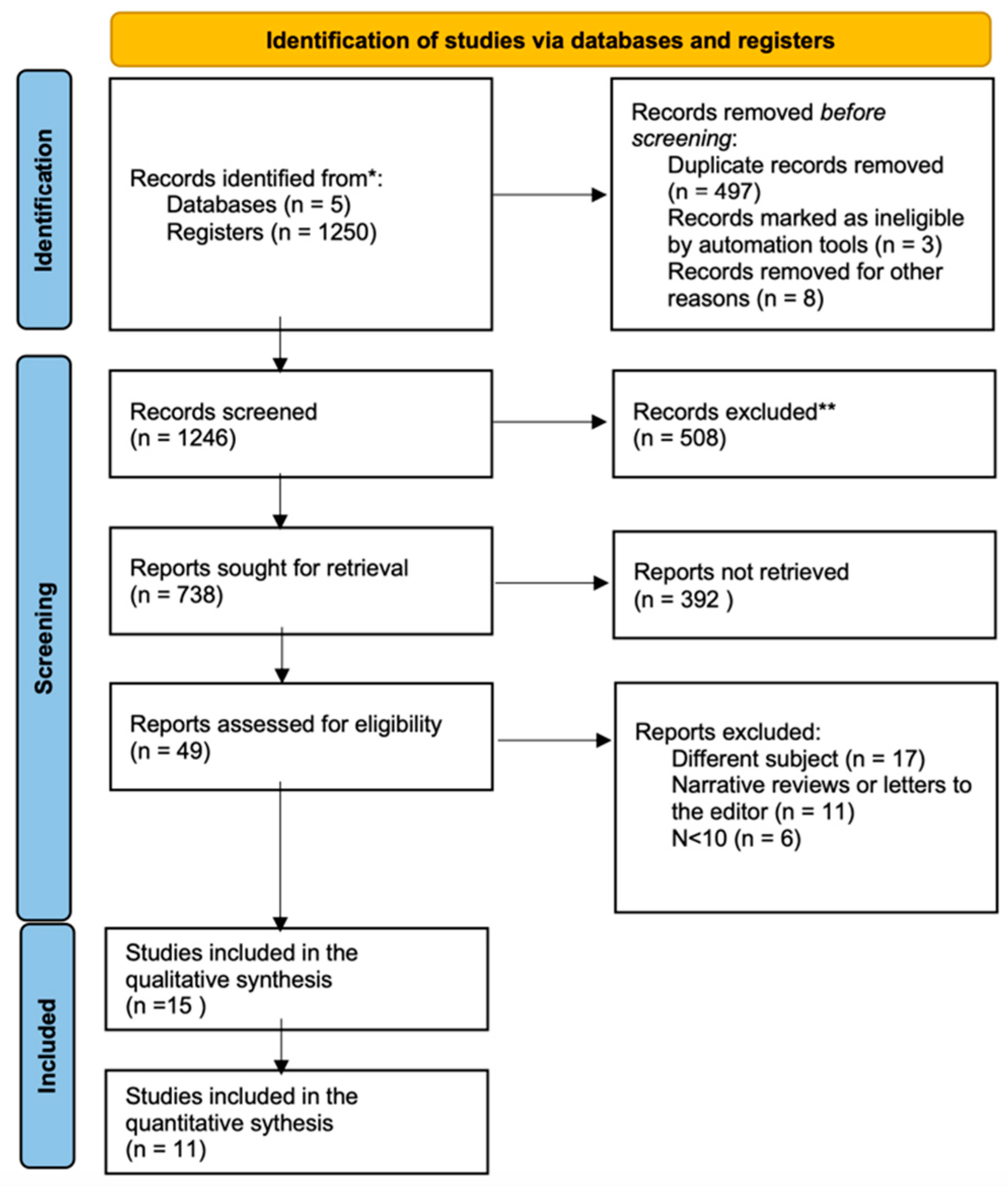

3.1. Results of the Search Process

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

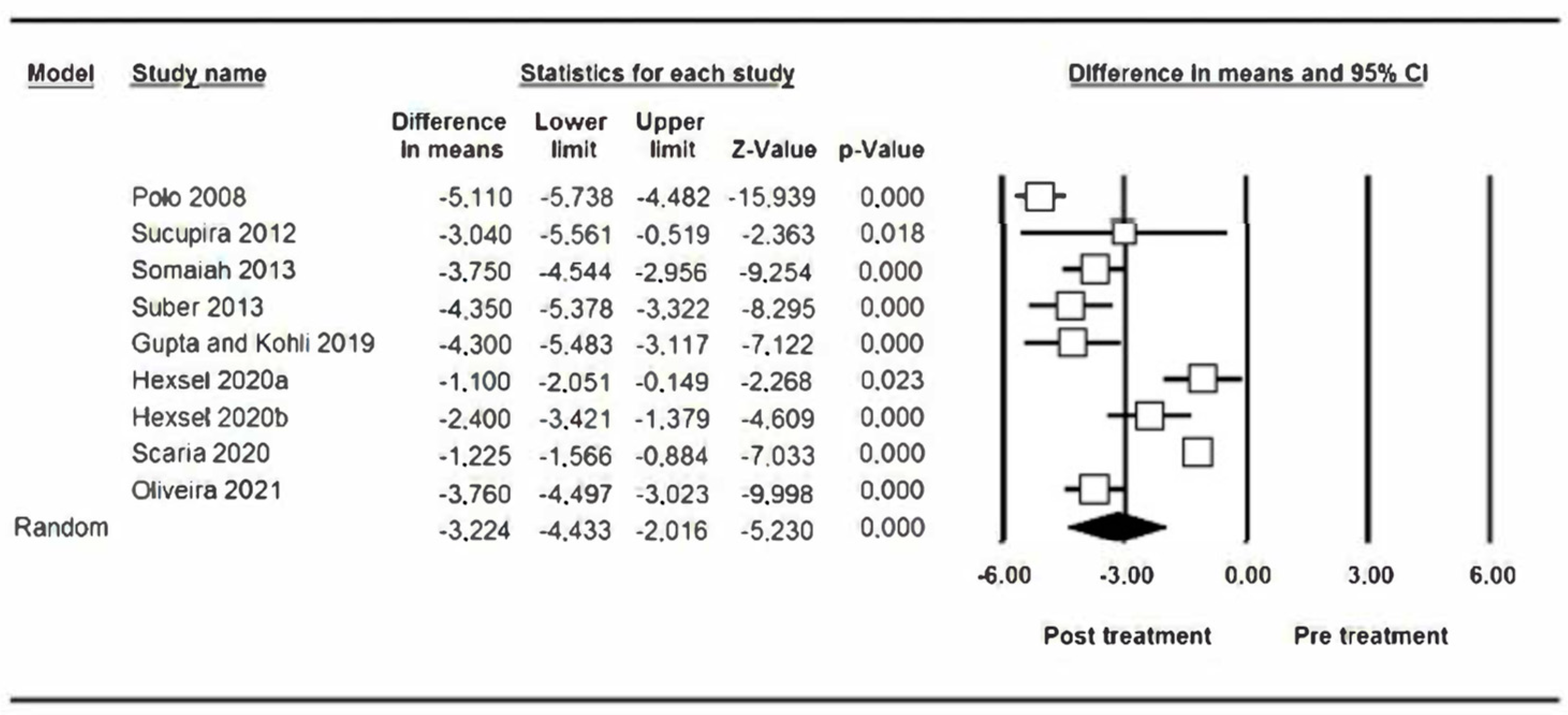

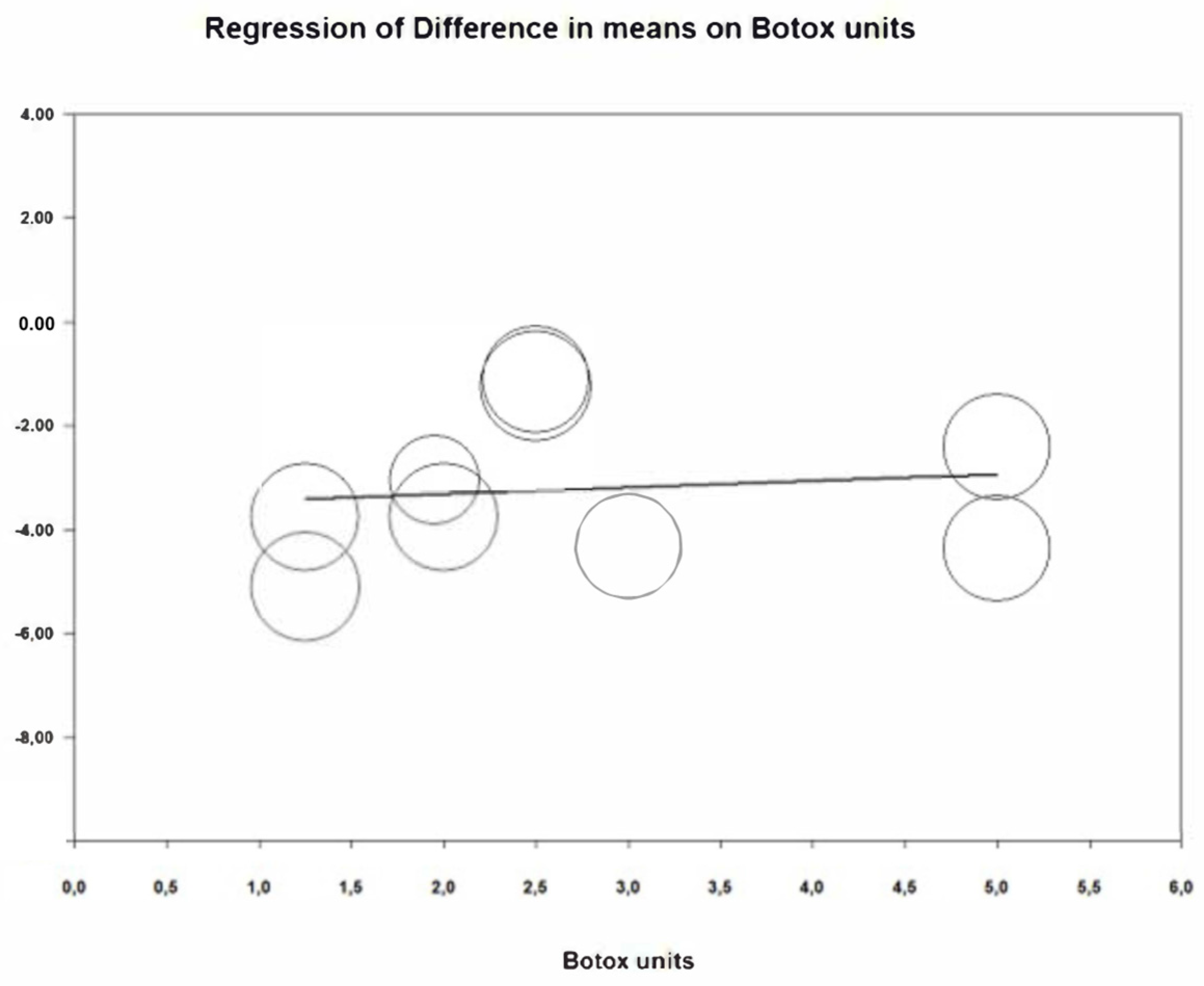

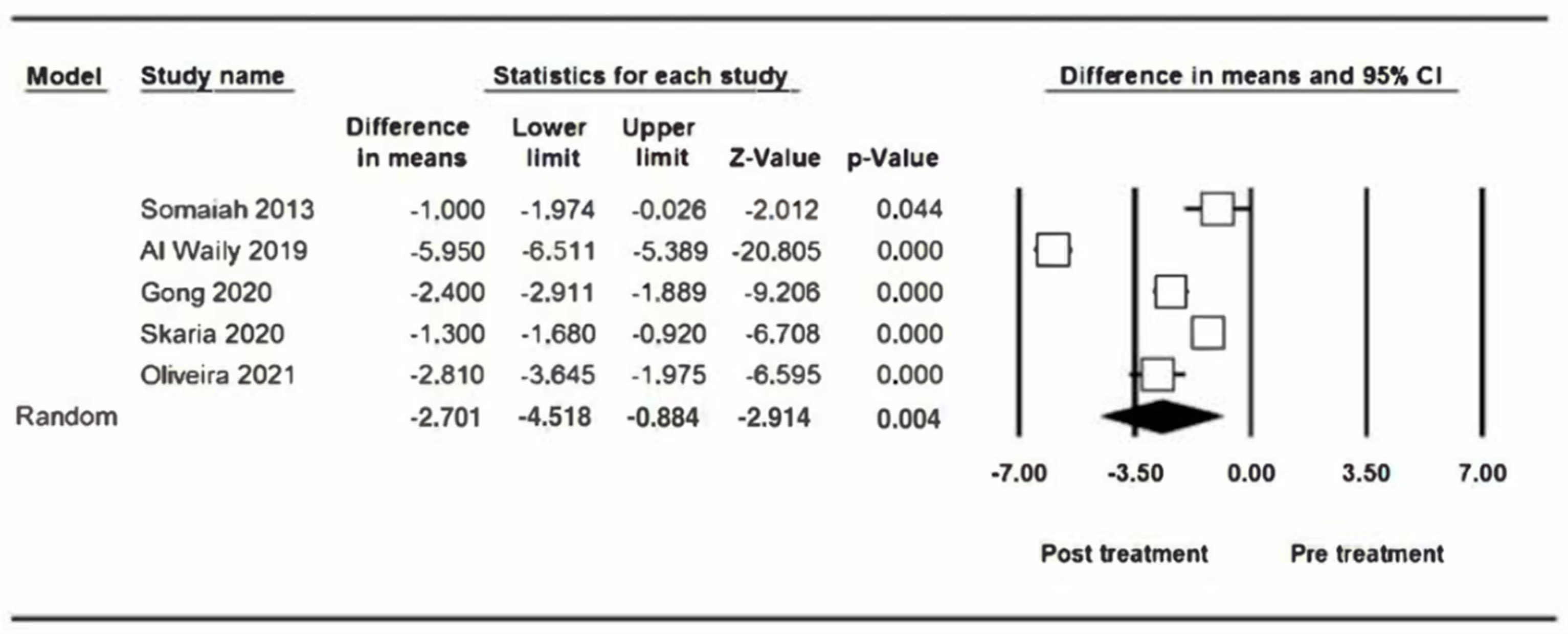

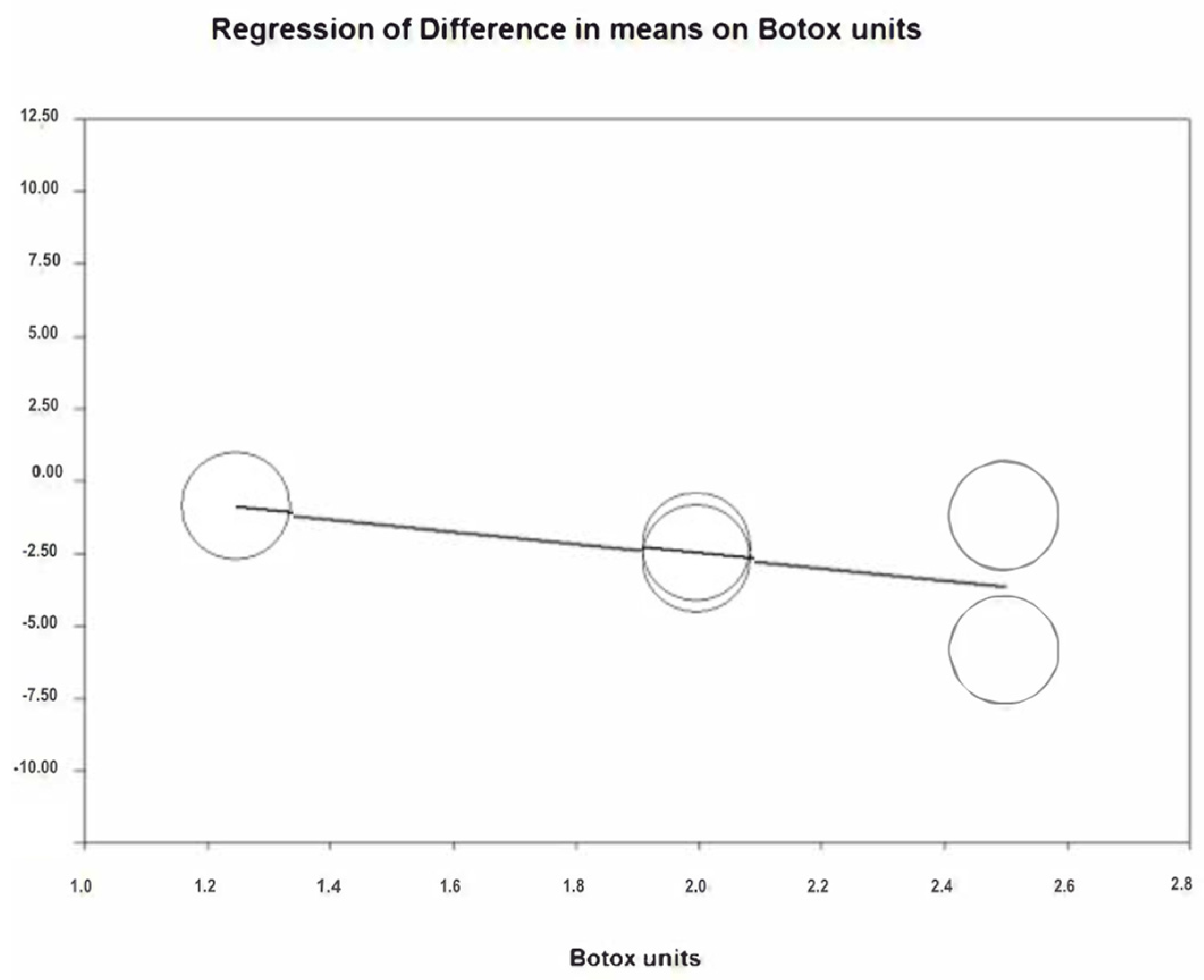

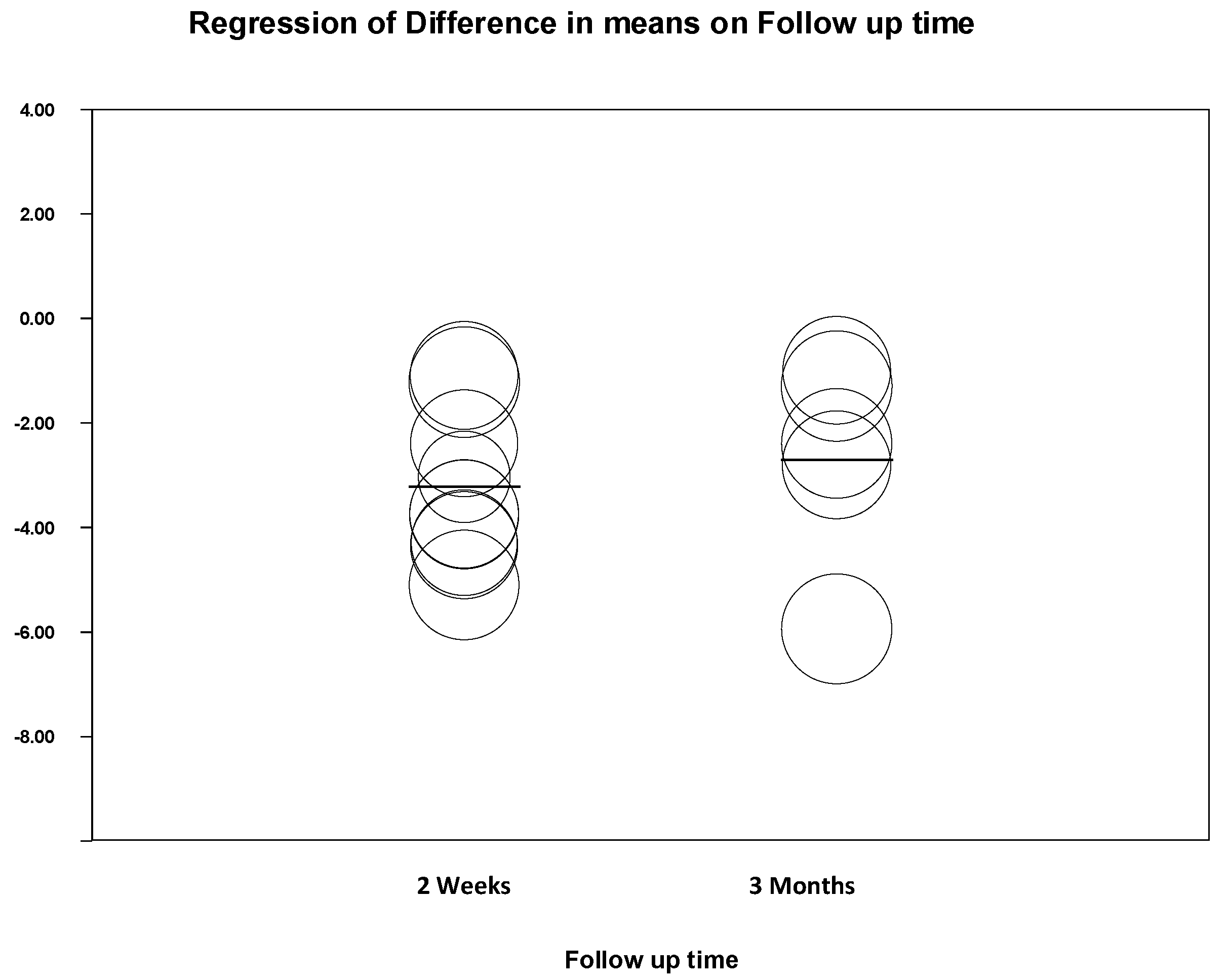

3.3. Quantitative Analysis Results

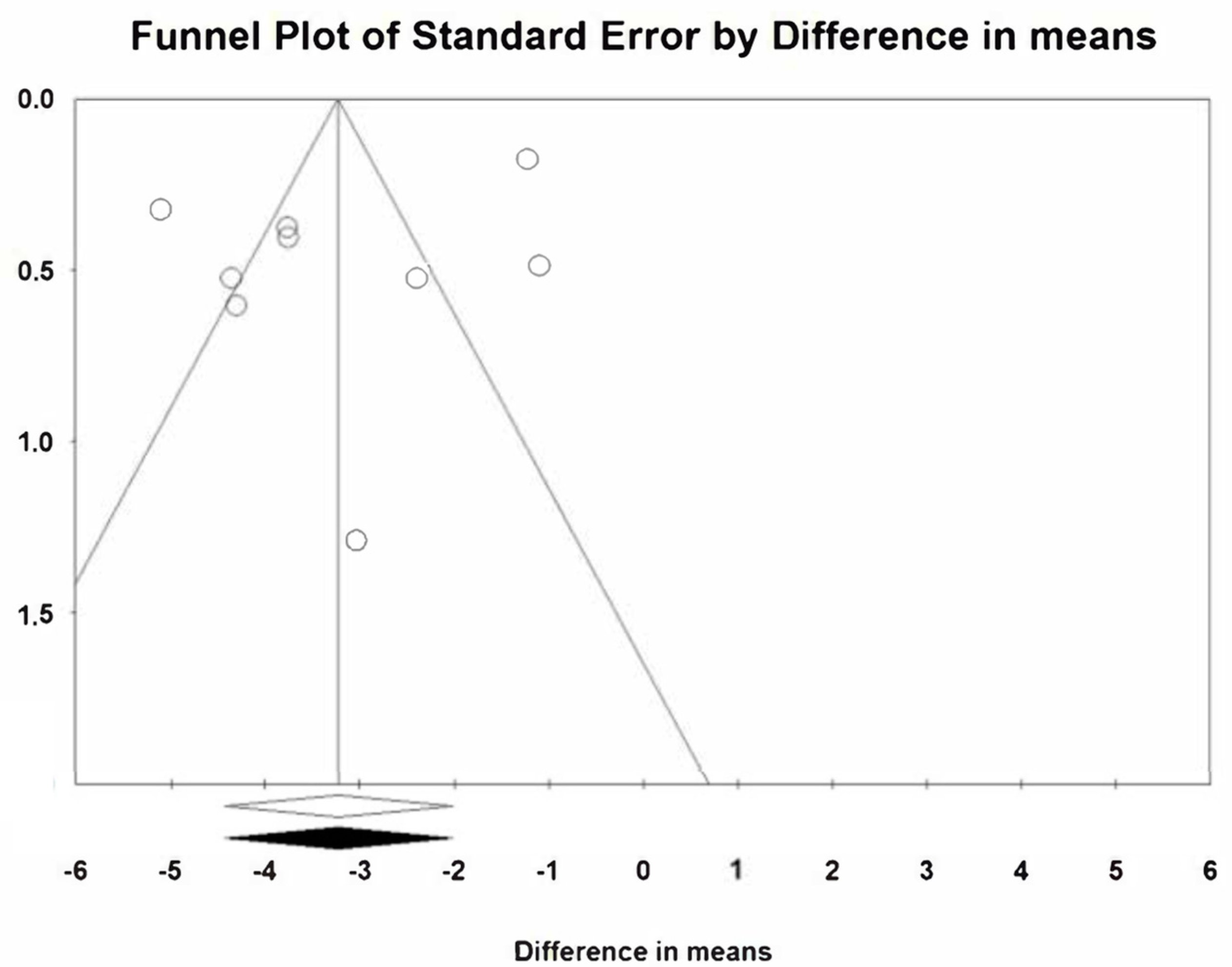

3.4. Publication Bias

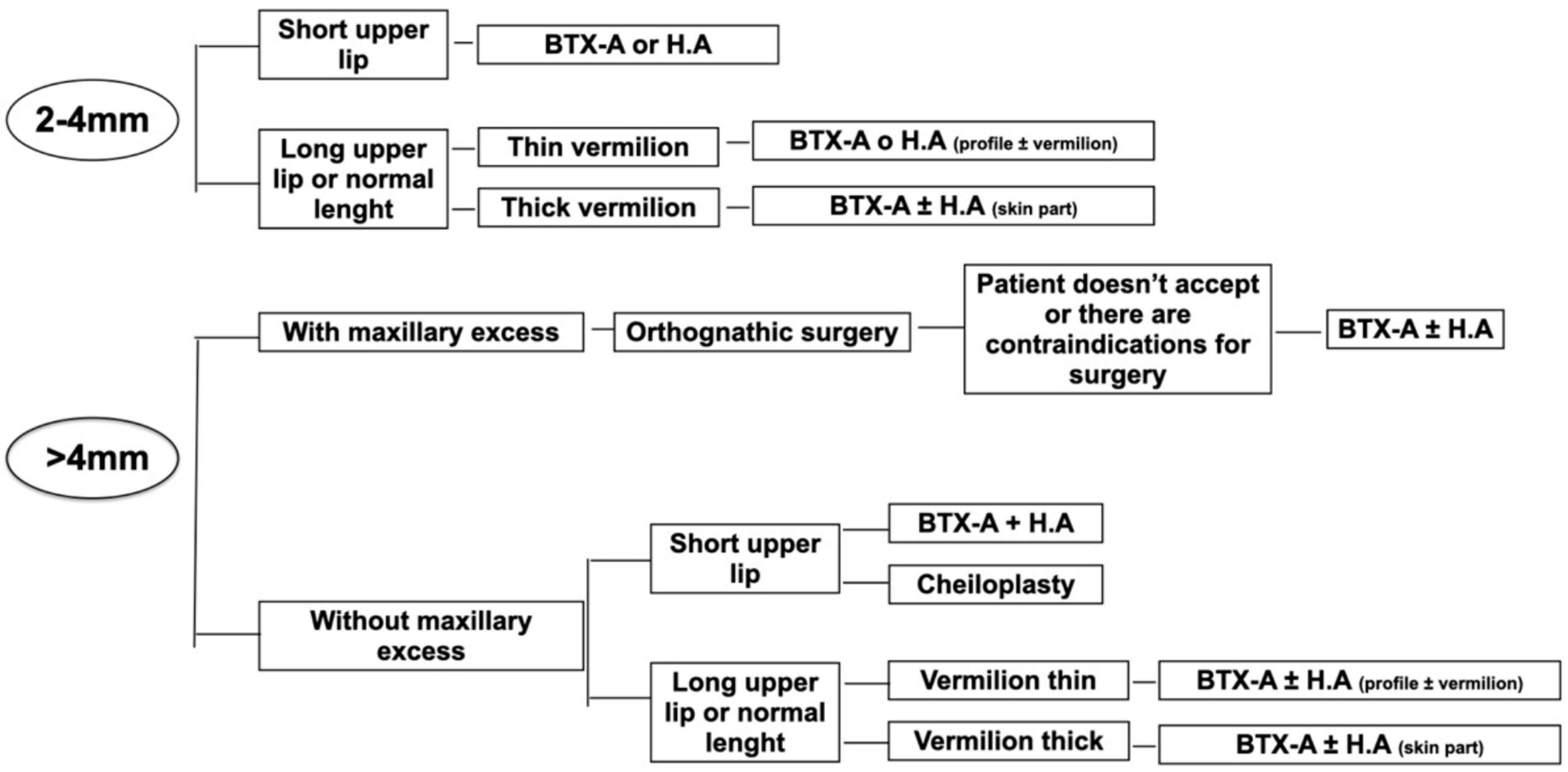

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A significant reduction in gummy smile is estimated by BTX-A therapy two weeks after its application with a reduction of 3.22 mm. Its results gradually decrease over time, however, they stay satisfactory without having returned to their initial values at 3 months.

- The number of infiltrated BTX-A units does not influence the reduction in gummy smile obtained after treatment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, M.B.; Ackerman, J.L. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J. Clin. Orthod. 2002, 36, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Fouzan, A.F.; Mokeem, L.S.; Al-Saqat, R.T.; Alfalah, M.A.; Alharbi, M.A.; Al-Samary, A.E. Botulinum Toxin for the Treatment of Gummv Smile. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriola, F.D.O.; Chieza, G.S.; Cavagni, J.; Freddo, A.L.; Corsetti, A. Management of excessive gingival display using botulinum toxin type A: A descriptive study. Toxicon 2021, 196, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.K.; Jin, T.H.; Cho, H.W.; Oh, S.C. The esthetics of the smile: A review of some recent studies. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1999, 12, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, L.; Aly, A.; Hammouda, N.I. Botox as an adjunct to lip repositioning for the management of excessive gingival display in the presence of hypermobility of upper lip and vertical maxillary excess. Dent. Res. J. 2016, 13, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhola, M.; Fairbairn, P.; Kolhatkar, S.; Chu, S.; Morris, T.; de Campos, M. LipStaT: The Lip Stabilization Technique—Indications and Guidelines for Case Selection and Classification of Excessive Gingival Display. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2015, 35, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, A.F.; Goymen, M.; Akcali, C. Efficacy of botulinum toxin for treating a gummy smile. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 158, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucupira, E.; Abramovitz, A. A simplified method for smile enhancement: Botulinum toxin injection for gummy smile. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 130, 726–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devgan, L.; Singh, P.; Durairaj, K. Minimally Invasive Facial Cosmetic Procedures. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 52, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaspro, A.; Cavallini, M.; Piersini, P.; Sito, G. Gummy Smile Treatment: Proposal for a Novel Corrective Technique and a Review of the Literature. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2018, 38, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, T.; De Almeida, N.V.; Lisboa, C.O.; Ferreira, D.M.T.P.; Mattos, C.T.; Mucha, J.N. Duration of effectiveness of Botulinum toxin type A in excessive gingival display: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, C.R.; Primo, P.P.; De Freitas, D.S.; Oliveira, R.C.; De Oliveira, R.C.G.; Freitas, K.M.S.; Valarelli, F.P.; Cançado, R.H. Comparison of Botulinum Toxin and Orthognathic Surgery for Gummy Smile Correction. Open Dent. J. 2020, 14, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaiah, M.K.S.; Muddaiah, S.; Shetty, B.; Vijayananda, K.M.; Bhat, M.; Shetty, P.S. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin A, in unraveling gummy smile: A prospective clinical study. APOS Trends Orthod. 2013, 3, 54-8. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Mir, C.; Silva, E.; Barriga, M.I.; Lagravère, M.O.; Major, P.W. Lay person’s perception of smile aesthetics in dental and facial views. J. Orthod. 2004, 31, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, D.A.; Salama, M.A. The aesthetic smile: Diagnosis and treatment. Periodontology 1996, 11, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Huang, H.; Gu, C.; Li, F.; Zou, L.; An, Y.; Han, X.; Tang, Z. Individual Factors of Botulinum Type A in Treatment of Gummy Smile: A Prospective Study. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2021, 41, NP842–NP850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Kohli, S. Evaluation of a neurotoxin as an adjunctive treatment modality for the management of gummy smile. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 10, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hexsel, D.; Dal’Forno, T.; Camozzato, F.; Valente, I.; Soirefmann, M.; Silva, A.F.; Siega, C. Effects of different doses of abobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of anterior gingival smile. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2020, 313, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.-S.; Hur, M.-S.; Hu, K.-S.; Song, W.-C.; Koh, K.-S.; Baik, H.-S.; Kim, S.-T.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, K.-J. Surface Anatomy of the Lip Elevator Muscles for the Treatment of Gummy Smile Using Botulinum Toxin. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablik, J.; Monheit, G.D.; Yu, L.; Chang, G.; Gershkovich, J. Comparative Physical Properties of Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers. Dermatol. Surg. 2009, 35, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-García, J.; Rosso, P.; Gonzalvez-García, M.; José, J.C.; Fernández, M. Gummy Smile: Mercado-Rosso Classification System and Dynamic Restructuring with Hyaluronic Acid. Aesth. Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2338–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo, M. Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for the neuromuscular correction of excessive gingival display on smiling (gummy smile). Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Wayli, H. Versatility of botulinum toxin at the Yonsei point for the treatment of gummy smile. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2019, 14, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Polo, M. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of excessive gingival display. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2005, 127, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, R.; Hexsel, D. Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: A new approach based on the gingival exposure area. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 63, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, A.; Goyal, M.; Shukla, S.; Mittal, N. To evaluate the effect and longevity of Botulinum toxin type A (Botox®) in the management of gummy smile–A longitudinal study upto 4 years follow-up. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 11, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suber, J.S.; Dinh, T.P.; Prince, M.D.; Smith, P.D. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of a “gummy smile”. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2014, 34, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaria, J.; Hegde, N.; George, P.P.; Michael, T.; Sebastian, J. Botulinum Toxin Type-A for the Treatment of Excessive Gingival Display on Smiling. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nasr, M.W.; Jabbour, S.F.; Sidaoui, J.A.; Haber, R.N.; Kechichian, E.G. Botulinum Toxin for the Treatment of Excessive Gingival Display: A Systematic Review. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2015, 36, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maio, M.; Wu, W.T.L.; Goodman, G.J.; Monheit, G. Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 540E–550E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surek, C.C.; Guisantes, E.; Schnarr, K.; Jelks, G.; Beut, J. “no-Touch” Technique for Lip Enhancement. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 603e–613e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojo-Sanchis, C.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Tarazona-Álvarez, B.; Haas-Junior, O.L.; Peiró-Guijarro, M.A.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; Guijarro-Martínez, R. Non-Surgical Management of the Gingival Smile with Botulinum Toxin A—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041433

Rojo-Sanchis C, Montiel-Company JM, Tarazona-Álvarez B, Haas-Junior OL, Peiró-Guijarro MA, Paredes-Gallardo V, Guijarro-Martínez R. Non-Surgical Management of the Gingival Smile with Botulinum Toxin A—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041433

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojo-Sanchis, Carolina, José María Montiel-Company, Beatriz Tarazona-Álvarez, Orion Luiz Haas-Junior, María Aurora Peiró-Guijarro, Vanessa Paredes-Gallardo, and Raquel Guijarro-Martínez. 2023. "Non-Surgical Management of the Gingival Smile with Botulinum Toxin A—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041433

APA StyleRojo-Sanchis, C., Montiel-Company, J. M., Tarazona-Álvarez, B., Haas-Junior, O. L., Peiró-Guijarro, M. A., Paredes-Gallardo, V., & Guijarro-Martínez, R. (2023). Non-Surgical Management of the Gingival Smile with Botulinum Toxin A—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041433