Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Extraction

2.2. Data Analysis

- -

- Clinical diagnosis by a physician during the study or in recorded administrative data;

- -

- History of medication coherent to COPD diagnosis;

- -

- Physician ignoring a negative result of the spirometry.

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Overdiagnosis

3.4. Overtreatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Safiri, S.; Carson-Chahhoud, K.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Ahmadian Heris, J.; Ansarin, K.; Mansournia, M.A.; Collins, G.S.; Kolahi, A.A.; et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022, 378, e069679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakban, A.; Sin, D.D.; FitzGerald, J.M.; McManus, B.M.; Ng, R.; Hollander, Z.; Sadatsafavi, M. The Projected Epidemic of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Hospitalizations over the Next 15 Years. A Population-based Perspective. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doña, E.; Reinoso-Arija, R.; Carrasco-Hernandez, L.; Doménech, A.; Dorado, A.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Exploring Current Concepts and Challenges in the Identification and Management of Early-Stage COPD. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOLD (Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease). Spirometry for Health Care Providers. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_Spirometry_2010.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2010).

- Fernandez-Villar, A.; Soriano, J.B.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Overdiagnosis of COPD: Precise definitions and proposals for improvement. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, N.; Gershon, A.S.; Sin, D.D.; Tan, W.C.; Bourbeau, J.; Boulet, L.P.; Aaron, S.D. Underdiagnosis and Overdiagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Campos, J.L.; Tan, W.; Soriano, J.B. Global burden of COPD. Respirology 2016, 21, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyratos, D.; Chloros, D.; Michalopoulou, D.; Sichletidis, L. Estimating the extent and economic impact of under and overdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2016, 13, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, J.; Yip, S.W.S.; Idrose, N.S.; Hancock, K.; Abramson, M.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Walters, E.H.; Waidyatillake, N. Undiagnosed and ‘overdiagnosed’ COPD using postbronchodilator spirometry in primary healthcare settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.T.; Glasziou, P.; Dobler, C.C. Use of the terms “overdiagnosis” and “misdiagnosis” in the COPD literature: A rapid review. Breathe 2019, 15, e8–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Roisin, R. Twenty Years of GOLD (1997–2017). The Origins. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GOLD-Origins-Final-Version-mar19.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Quanjer, P.H.; Enright, P.L.; Miller, M.R.; Stocks, J.; Ruppel, G.; Swanney, M.P.; Crapo, R.O.; Pedersen, O.F.; Falaschetti, E.; Schouten, J.P.; et al. The need to change the method for defining mild airway obstruction. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 37, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Gori, D.; Leoni, E.; Rochira, A.; Dallolio, L. Evaluation of school-based interventions of active breaks in primary schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2020, 23, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arne, M.; Lisspers, K.; Stallberg, B.; Boman, G.; Hedenstrom, H.; Janson, C.; Emtner, M. How often is diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometry? Respir. Med. 2010, 104, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, C.E.; Ionescu, A.A.; Edwards, P.H.; Faulkner, T.A.; Edwards, S.M.; Shale, D.J. Attaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practice. Respir. Med. 2005, 99, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas Herrera, A.; Montes de Oca, M.; Lopez Varela, M.V.; Aguirre, C.; Schiavi, E.; Jardim, J.R.; Team, P. COPD Underdiagnosis and Misdiagnosis in a High-Risk Primary Care Population in Four Latin American Countries. A Key to Enhance Disease Diagnosis: The PUMA Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, N.F.; Soyseth, V.; Lyngbakken, M.N.; Berge, T.; Ariansen, I.; Tveit, A.; Rosjo, H.; Einvik, G. Treatable Traits in Misdiagnosed Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Data from the Akershus Cardiac Examination 1950 Study. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2022, 9, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.F.; Ramenofsky, D.; Au, D.H.; Ma, J.; Uman, J.E.; Feemster, L.C. The association of weight with the detection of airflow obstruction and inhaled treatment among patients with a clinical diagnosis of COPD. Chest 2014, 146, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, A.; Uçar, E.Y.; Araz, Ö.; Sağlam, L.; Mirici, N.A. Contribution of spirometry to early diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary health care centers. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 43, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.J.; Yadegarfar, M.E.; Collerton, J.; Small, T.; Kirkwood, T.B.; Davies, K.; Jagger, C.; Corris, P.A. Respiratory health and disease in a U.K. population-based cohort of 85 year olds: The Newcastle 85+ Study. Thorax 2016, 71, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, M.; McMillan, V.; Brown, J.; Holzhauer-Barrie, J.; Khan, M.S.; Baxter, N.; Roberts, C.M. Inaccurate diagnosis of COPD: The Welsh National COPD Audit. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, A.S.; Thiruchelvam, D.; Chapman, K.R.; Aaron, S.D.; Stanbrook, M.B.; Bourbeau, J.; Tan, W.; To, T.; Canadian Respiratory Research, N. Health Services Burden of Undiagnosed and Overdiagnosed COPD. Chest 2018, 153, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghattas, C.; Dai, A.; Gemmel, D.J.; Awad, M.H. Over diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an underserved patient population. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2013, 8, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guder, G.; Brenner, S.; Angermann, C.E.; Ertl, G.; Held, M.; Sachs, A.P.; Lammers, J.W.; Zanen, P.; Hoes, A.W.; Stork, S.; et al. GOLD or lower limit of normal definition? A comparison with expert-based diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a prospective cohort-study. Respir. Res. 2012, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamers, R.; Bontemps, S.; van den Akker, M.; Souza, R.; Penaforte, J.; Chavannes, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Brazilian primary care: Diagnostic competence and case-finding. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2006, 15, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Heffler, E.; Crimi, C.; Mancuso, S.; Campisi, R.; Puggioni, F.; Brussino, L.; Crimi, N. Misdiagnosis of asthma and COPD and underuse of spirometry in primary care unselected patients. Respir. Med. 2018, 142, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, K.; Goldstein, R.S.; Guyatt, G.H.; Blouin, M.; Tan, W.C.; Davis, L.L.; Heels-Ansdell, D.M.; Erak, M.; Bragaglia, P.J.; Tamari, I.E.; et al. Prevalence and underdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients at risk in primary care. CMAJ 2010, 182, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasse, Y.; Daigle, J.M.; Martin, S.; Maltais, F. Validity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnoses in a large administrative database. Can. Respir. J. 2012, 19, e5–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, B.; Mahringer, A.; Soriano, J.B.; Kaiser, B.; Buist, A.S.; Studnicka, M. Is spirometry properly used to diagnose COPD? Results from the BOLD study in Salzburg, Austria: A population-based analytical study. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2013, 22, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, B.; Soriano, J.B.; Studnicka, M.; Kaiser, B.; Vanfleteren, L.E.; Gnatiuc, L.; Burney, P.; Miravitlles, M.; García-Rio, F.; Akbari, K.; et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest 2015, 148, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laniado-Laborin, R.; Rendon, A.; Bauerle, O. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease case finding in Mexico in an at-risk population. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Abramson, M.J.; Zwar, N.A.; Russell, G.M.; Holland, A.E.; Bonevski, B.; Mahal, A.; Phillips, K.; Eustace, P.; Paul, E.; et al. Diagnosing COPD and supporting smoking cessation in general practice: Evidence-practice gaps. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llordes, M.; Jaen, A.; Almagro, P.; Heredia, J.L.; Morera, J.; Soriano, J.B.; Miravitlles, M. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Diagnostic Accuracy of COPD Among Smokers in Primary Care. COPD 2015, 12, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melbye, H.; Drivenes, E.; Dalbak, L.G.; Leinan, T.; Hoegh-Henrichsen, S.; Ostrem, A. Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or both? Diagnostic labeling and spirometry in primary care patients aged 40 years or more. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2011, 6, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Minasian, A.G.; van den Elshout, F.J.; Dekhuijzen, P.N.; Vos, P.J.; Willems, F.F.; van den Bergh, P.J.; Heijdra, Y.F. COPD in chronic heart failure: Less common than previously thought? Heart Lung 2013, 42, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles, M.; Andreu, I.; Romero, Y.; Sitjar, S.; Altes, A.; Anton, E. Difficulties in differential diagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, e68–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U, M.S.; Leong, W.K.; Wun, Y.T.; Tse, S.F. A study on COPD in primary care: Comparing correctly and incorrectly diagnosed patients. HK Pract. 2015, 37, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, K.; Toelle, B.G.; Wood-Baker, R.; Maguire, G.P.; James, A.L.; Hunter, M.; Johns, D.P.; Marks, G.B.; George, J.; Abramson, M.J. Undiagnosed and Misdiagnosed Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Data from the BOLD Australia Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.C.; Moreira, M.A.; Rabahi, M.F. Underdiagnosis of COPD at primary health care clinics in the city of Aparecida de Goiania, Brazil. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2012, 38, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaisiene, G.; Kibarskyte, R.; Gauronskaite, R.; Giedraityte, M.; Dapsauskaite, A.; Kasiulevicius, V.; Danila, E. Diagnosing COPD in primary care: What has real life practice got to do with guidelines? Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2019, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddel, H.K.; Vestbo, J.; Agusti, A.; Anderson, G.P.; Bansal, A.T.; Beasley, R.; Bel, E.H.; Janson, C.; Make, B.; Pavord, I.D.; et al. Heterogeneity within and between physician-diagnosed asthma and/or COPD: NOVELTY cohort. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2003927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, R.D.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Al-Jaghbeer, M.J. COPD Overdiagnosis and Its Effect on 30-Day Hospital Readmission Rates. Respir. Care 2021, 66, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M.; Abedi, M.K.A.; Barry, J.S.; Williams, E.; Quantrill, S.J. Predictive value of primary care made clinical diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with secondary care specialist diagnosis based on spirometry performed in a lung function laboratory. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2009, 10, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sator, L.; Horner, A.; Studnicka, M.; Lamprecht, B.; Kaiser, B.; McBurnie, M.A.; Buist, A.S.; Gnatiuc, L.; Mannino, D.M.; Janson, C.; et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in Subjects With Unobstructed Spirometry: A BOLD Analysis. Chest 2019, 156, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.; Gindner, L.; Tilemann, L.; Schermer, T.; Dinant, G.J.; Meyer, F.J.; Szecsenyi, J. Diagnostic accuracy of spirometry in primary care. BMC Pulm. Med. 2009, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichletidis, L.; Chloros, D.; Spyratos, D.; Chatzidimitriou, N.; Chatziiliadis, P.; Protopappas, N.; Charalambidou, O.; Pelagidou, D.; Zarvalis, E.; Patakas, D. The validity of the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2007, 16, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spero, K.; Bayasi, G.; Beaudry, L.; Barber, K.R.; Khorfan, F. Overdiagnosis of COPD in hospitalized patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017, 12, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyratos, D.; Chloros, D.; Michalopoulou, D.; Tsiouprou, I.; Christoglou, K.; Sichletidis, L. Underdiagnosis, false diagnosis and treatment of COPD in a selected population in Northern Greece. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starren, E.S.; Roberts, N.J.; Tahir, M.; O’Byrne, L.; Haffenden, R.; Patel, I.S.; Partridge, M.R. A centralised respiratory diagnostic service for primary care: A 4-year audit. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2012, 21, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamo, C.; de Oca, M.M.; Halbert, R.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Jardim, J.R.; Muino, A.; Lopez, M.V.; Valdivia, G.; Pertuze, J.; Moreno, D.; et al. Diagnostic labeling of COPD in five Latin American cities. Chest 2007, 131, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkelman, D.G.; Price, D.B.; Nordyke, R.J.; Halbert, R.J. Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J. Asthma 2006, 43, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, J.A.; Walters, E.H.; Nelson, M.; Robinson, A.; Scott, J.; Turner, P.; Wood-Baker, R. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of COPD in primary care. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2011, 20, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.; Thornton, H.; Pinnock, H.; Georgopoulou, S.; Booth, H.P. Overtreatment of COPD with inhaled corticosteroids--implications for safety and costs: Cross-sectional observational study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwar, N.A.; Marks, G.B.; Hermiz, O.; Middleton, S.; Comino, E.J.; Hasan, I.; Vagholkar, S.; Wilson, S.F. Predictors of accuracy of diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 195, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohar, J.A.; Sadeghnejad, A.; Meyers, D.A.; Donohue, J.F.; Bleecker, E.R. Do symptoms predict COPD in smokers? Chest 2010, 137, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.F. Chronic ‘cough hypersensitivity syndrome’: A more precise label for chronic cough. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 24, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.K.; Agusti, A.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Roche, N.; Papi, A.; Stockley, R.A.; Wedzicha, J.; Vogelmeier, C.F. From GOLD 0 to Pre-COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, E.F.M.; Breyer, M.K.; Breyer-Kohansal, R.; Hartl, S. COPD Diagnosis: Time for Disruption. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.V.; Allison, D.R.; Andrews, S.; Mejia, J.; Mills, P.K.; Peterson, M.W. Misdiagnosis Among Frequent Exacerbators of Clinically Diagnosed Asthma and COPD in Absence of Confirmation of Airflow Obstruction. Lung 2015, 193, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Rhee, C.K. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (COPD). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.J.; Smith, S.F.; Partridge, M.R. Why is spirometry underused in the diagnosis of the breathless patient: A qualitative study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2011, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindensmith, J.; Morrison, D.; Deveau, C.; Hernandez, P. Overdiagnosis of asthma in the community. Can. Respir. J. 2004, 11, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, J.; Loves, R.H.; Aaron, S.D. Addressing the misdiagnosis of asthma in adults: Where does it go wrong? Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2016, 10, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothnie, K.J.; Chandan, J.S.; Goss, H.G.; Mullerova, H.; Quint, J.K. Validity and interpretation of spirometric recordings to diagnose COPD in UK primary care. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2017, 12, 1663–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maue, S.K.; Segal, R.; Kimberlin, C.L.; Lipowski, E.E. Predicting physician guideline compliance: An assessment of motivators and perceived barriers. Am. J. Manag. Care 2004, 10, 383–391. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana, M.D.; Rand, C.S.; Powe, N.R.; Wu, A.W.; Wilson, M.H.; Abboud, P.A.; Rubin, H.R. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. Jpn. Automob. Manuf. Assoc. 1999, 282, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busfield, J. Assessing the overuse of medicines. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 131, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossaki, F.M.; Hurst, J.R.; van Gemert, F.; Kirenga, B.J.; Williams, S.; Khoo, E.M.; Tsiligianni, I.; Tabyshova, A.; van Boven, J.F. Strategies for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COPD in low- and middle- income countries: The importance of primary care. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2021, 15, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.A.; Fromer, L. Spirometry use: Detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Clin. Interv. Aging 2011, 6, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- AIFA (Italian Medicines Agency). Nota 99. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/nota-99 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Armstrong, N. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment as a quality problem: Insights from healthcare improvement research. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, M.; Tisdell, J.; Zimitat, C. “Too much medicine”: Insights and explanations from economic theory and research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 176, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S.; Cook, C.E.; Hoffmann, T.C.; O’Sullivan, P. The Elephant in the Room: Too Much Medicine in Musculoskeletal Practice. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, R.; Doust, J.; Henry, D. Preventing overdiagnosis: How to stop harming the healthy. BMJ 2012, 344, e3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M.; Hackbarth, A.D. Eliminating waste in US health care. Jpn. Automob. Manuf. Assoc. 2012, 307, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. Global Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Therapeutics Market by Drug Class, Distribution Channel. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/4989588/global-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Steinacher, R.; Parissis, J.T.; Strohmer, B.; Eichinger, J.; Rottlaender, D.; Hoppe, U.C.; Altenberger, J. Comparison between ATS/ERS age- and gender-adjusted criteria and GOLD criteria for the detection of irreversible airway obstruction in chronic heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2012, 101, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hoesein, F.A.; Zanen, P.; Sachs, A.P.; Verheij, T.J.; Lammers, J.W.; Broekhuizen, B.D. Spirometric thresholds for diagnosing COPD: 0.70 or LLN, pre- or post-dilator values? COPD 2012, 9, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, J.A.; Buist, A.S.; Vollmer, W.M.; Ellingsen, I.; Bakke, P.S.; Morkve, O. Risk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 20, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K. The Pitfalls of Overtreatment: Why More Care is not Necessarily Beneficial. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 2020, 12, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Berlin, J.A.; Gopalan, R.; Matthews, D.R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991, 337, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, M.; Green, A.; Goyder, E.; Miles, G.; Lee, A.C.; Basran, G.; Cooke, J. Accuracy of diagnosis and classification of COPD in primary and specialist nurse-led respiratory care in Rotherham, UK: A cross-sectional study. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2014, 23, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmi, O.P.; Li, L.; Smith, M.; Augustyn, M.; Chen, J.; Collins, R.; Guo, Y.; Han, Y.; Qin, J.; Xu, G.; et al. Regional variations in the prevalence and misdiagnosis of air flow obstruction in China: Baseline results from a prospective cohort of the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB). BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2014, 1, e000025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.M.; Van Meer, O.; Keijzers, G.; Motiejunaite, J.; Jones, P.; Body, R.; Craig, S.; Karamercan, M.; Klim, S.; Harjola, V.P.; et al. AANZDEM and EuroDEM Study Groups. Get with the guidelines: Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in emergency departments in Europe and Australasia is sub-optimal. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

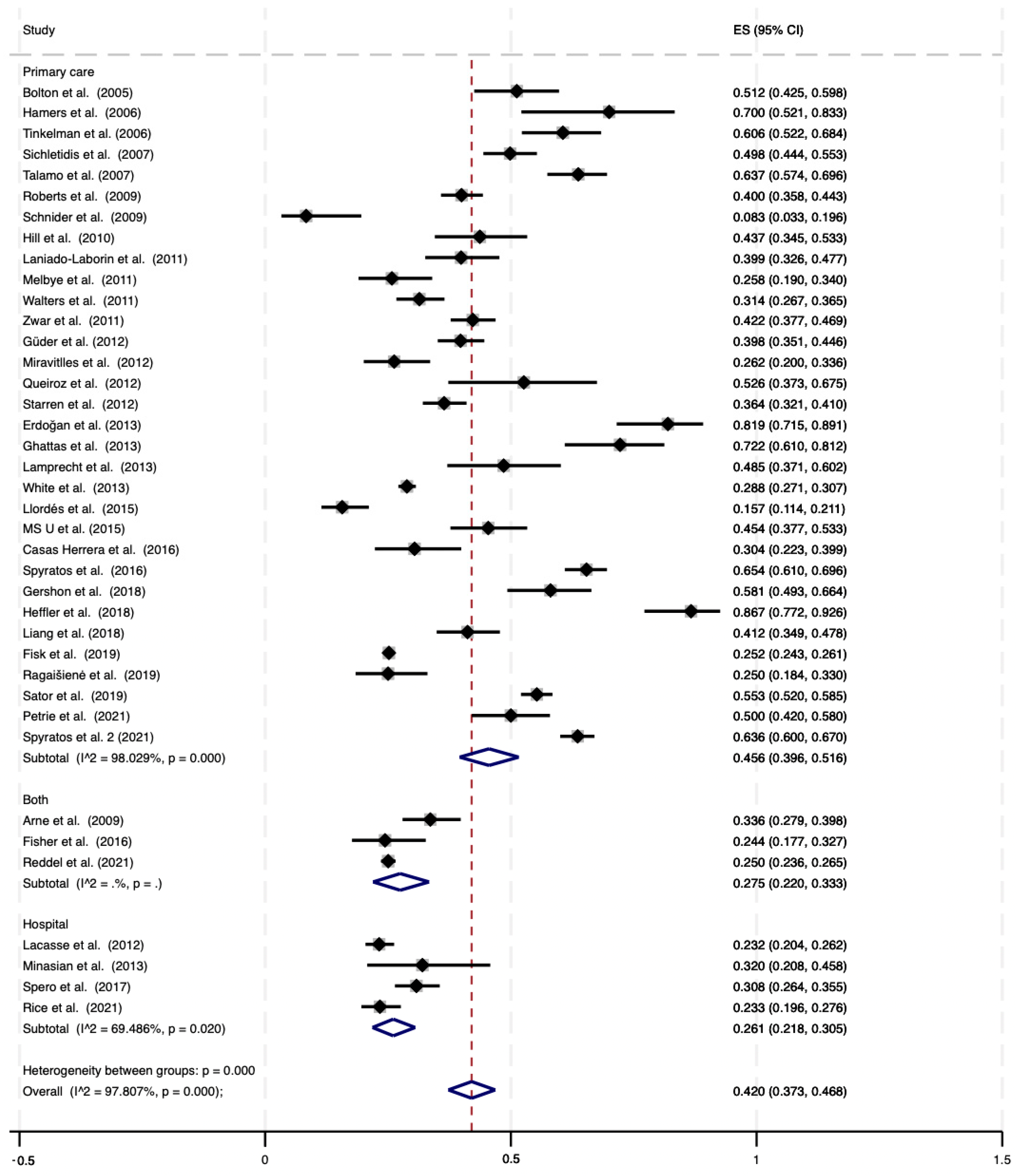

| Outcome: Overdiagnosis | Study Ref. | N. Datasets (n/N) a | Pooled Rates % (95% CI) | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD Definition: GOLD | ||||

| Overall sample | 39 (7710/23,765) | 42.0 (37.3–46.8) | 97.8% | |

| Primary care/ general population setting | [8,17,18,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,31,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] | 32 (6356/18,450) | 45.6 (39.6–51.6) | 98.0% |

| Hospital/ healthcare center setting | [30,37,44,49] | 4 (421/1666) | 26.1 (21.8–30.5) | 69.5% |

| Hospital/inpatients | [30,44,49] | 3 (405/1616) | 25.5(21.1–30.2) | -- |

| Hospital/outpatients | [37] | 1 (16/50) | 32.0 (19.5–46.7) | -- |

| Both settings | [16,22,43] | 3 (933/3649) | 27.5 (22.0–33.3) | -- |

| COPD Definition: LLN | ||||

| Overall sample | 10 (5917/12,455) | 48.2 (40.6–55.9) | 98.3% | |

| Primary care/ general population setting | [32,40,46] | 3 (1619/2611) | 55.9 (46.1–65.5) | -- |

| Hospital/ healthcare center setting | [19,20,37,44,49] | 5 (3070/6521) | 43.8 (34.4–53.4) | 95.1% |

| Both settings | [22,43] | 2 (1228/3323) | 36.9 (35.2–38.5) | -- |

| Outcome: Overtreatment | Study ref. | N. datasets (n/N) b | Pooled rates % (95% CI) | I2, % |

| COPD Definition: GOLD | [8,23,25,26,39,50,51,53,54,55,56] | 11 (2807/4842) | 57.1 (40.9–72.6) | 99.1% |

| COPD Definition: LLN | [19,20,46] | 3 (1570/3341) | 36.3 (17.8–57.2) | 98.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiore, M.; Ricci, M.; Rosso, A.; Flacco, M.E.; Manzoli, L. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226978

Fiore M, Ricci M, Rosso A, Flacco ME, Manzoli L. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(22):6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226978

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiore, Matteo, Matteo Ricci, Annalisa Rosso, Maria Elena Flacco, and Lamberto Manzoli. 2023. "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: A Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 22: 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226978

APA StyleFiore, M., Ricci, M., Rosso, A., Flacco, M. E., & Manzoli, L. (2023). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(22), 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226978