Suicidal Ideation and Death by Suicide as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spanish-Speaking Countries: Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Selecting the scientific evidence on suicidal ideation and death by suicide resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish-speaking countries;

- -

- Analyzing the scientific evidence on suicidal ideation and death by suicide resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish-speaking countries.

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria for Articles

- -

- Study period: January 2021–May 2023;

- -

- Article language: Spanish or English;

- -

- Language of the country where the study was conducted: Spanish;

- -

- Article type: original;

- -

- Open access article;

- -

- Countries where the study was conducted: Spain, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile, and Peru;

- -

- The sample revealed suicidal ideation and death by suicide between January 2021 and May 2023, the period in which the World Health Organization declared the end of the health emergency.

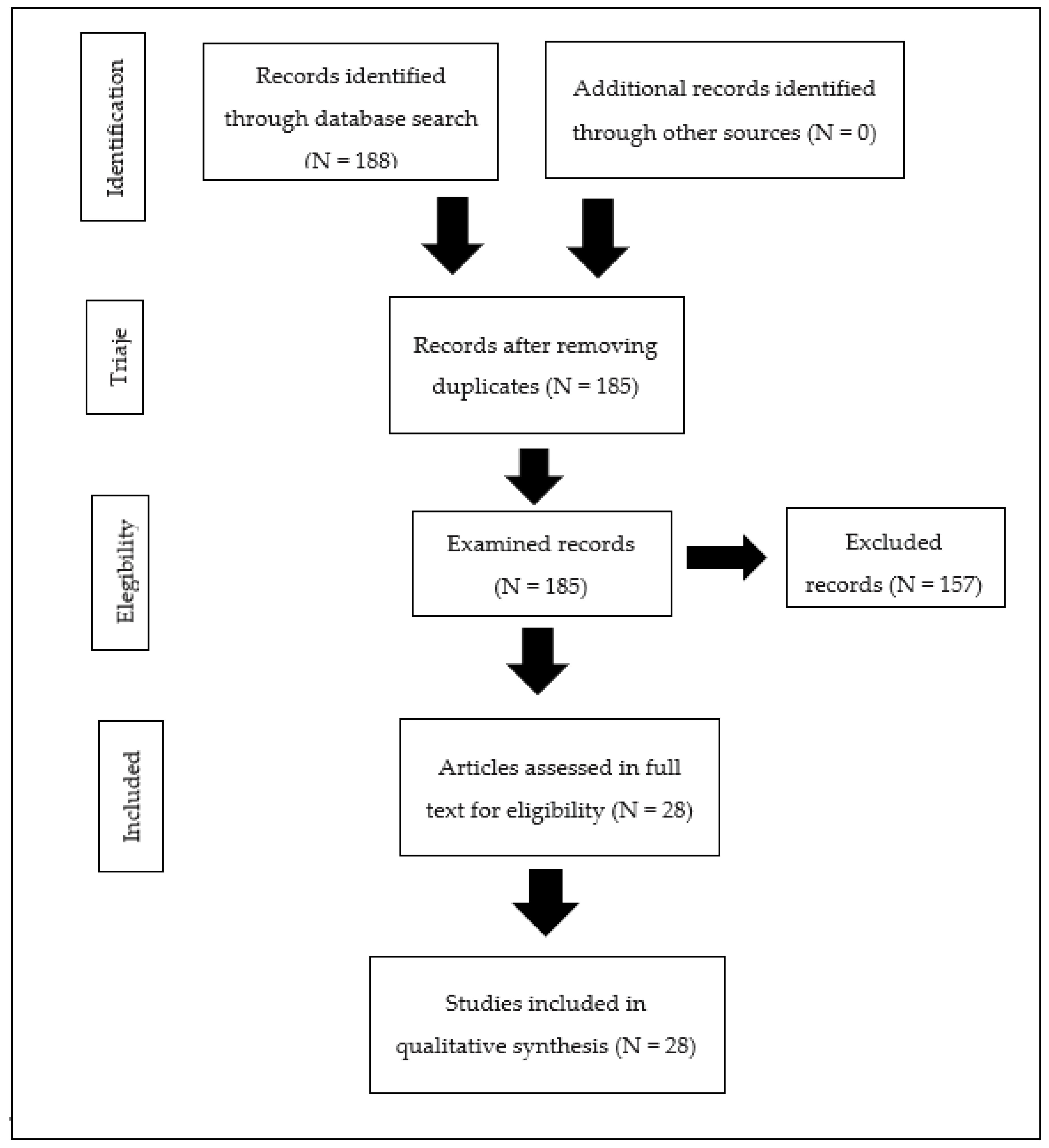

2.2. Sources of Information, Search Strategy, Study Selection Process, and Data Selection Process

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

- (a)

- Age:

- (b)

- Gender:

- (c)

- Socioeconomic level:

- (d)

- Risk factors such as living in rural areas, unemployment, and family death due to COVID-19:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mejía-Zambrano, H.; Ramos-Calsín, L. Prevalencia de los principales trastornos mentales durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Rev. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2022, 85, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Gómez, N. El suicidio en jóvenes en España: Cifras y posibles causas. Análisis de los últimos datos disponibles. Clínica Y Salud 2017, 28, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciones Unidas. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Una Oportunidad Para América Latina y El Caribe (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3). Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/ (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Bustamante, F.; Urquidi, C.; Florenzano, R.; Barrueto, C.; Hoyos, J.; Ampuero, K.; Terán, L.; Figueroa, M.I.; Farías, M.; Rueda, M.L.; et al. El programa RADAR para la prevención del suicidio en adolescentes de la región de Aysén, Chile: Resultados preliminares. Rev. Chil. Pediatría 2018, 89, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana, A. The engaged community action for preventing suicide (ECAPS) model in Latin America: Development of the ¡PEDIR! program. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/57504 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Salinas-Rodríguez, A.; Argumedo, G.; Hernández-Alcaraz, C.; Contreras-Manzano, A.; Jáuregui, A. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale: Factor validation during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Mexico. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2023, 55, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voz de América. Available online: https://www.vozdeamerica.com/a/la-ops-advierte-grave-deterioro-de-salud-mental-en-latinoamerica-y-apuntala-plan-para-hacer-frente-al-problema/7130756.html (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Arilla-Andrés, S.; García-Martínez, C.; Lopez-Del Hoyo, Y. Detección del riesgo de suicidio a través de las redes sociales. Int. Technol. Sci. Soc. Rev. 2022, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrani, D. Psychometric validation of the Columbia-Suicide Severity rating scale in Spanish-speaking adolescents. Colomb. Médica 2017, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Financiero. Available online: https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/salud/2022/09/09/las-personas-que-han-padecido-covid-son-mas-vulnerables-al-suicidio-esto-revela-un-estudio/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Urdiales, R.; Sánchez, N. Sintomatología depresiva e ideación suicida como consecuencia de la pandemia por la COVID-19. Escr. Psicol. 2021, 14, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Americana de Psicología. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/prevencion-suicidio (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Bouza, E.; Arango, C.; Moreno, C.; Gracia, D.; Martín, M.; Pérez, V.; Lázaro, L.; Ferre, F.; Salazar, G.; Tejerina-Picado, F.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the general population and health care workers. Rev. Española De Quimioter. 2023, 36, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Bevilacqua, P. Depresión y Riesgo de Suicidio en Trabajadoras Sexuales. Gac. Médica Boliv. 2021, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; George, R.; Mohanan, M. Background of suicide amidst COVID-19 pandemic in India: A review of published literature. Ann. Indian Psychiatry 2022, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil, J. Suicide Attempt Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Emergency Department Comparative Study. Semergen 2023, 43, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Comercio. Available online: https://elcomercio.pe/peru/mas-de-6-mil-peruanos-fallecieron-por-suicidio-durante-los-ultimos-10-anos-prevencion-del-suicidio-posvencion-peru-ayuda-ecdata-noticia/ (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- El Heraldo. Available online: https://heraldodemexico.com.mx/mundo/2023/6/16/durante-la-pandemia-de-covid-19-se-incrementaron-los-suicidios-en-jovenes-514501.html (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Infobae. Available online: https://www.infobae.com/salud/2023/05/05/vigilancia-epidemiologica-del-suicidio-adicciones-y-asistencia-post-covid-15-claves-del-plan-de-salud-mental-en-argentina/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Suárez, Y. Estrategias para la prevención del suicidio. Med. UPB 2023, 42, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culebras, J.; San Mauro, M.; Vicente-Vacas, L. COVID-19 y otras pandemias. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2020, 5, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, F.; Candilis, P. Pandemics and Suicide Risk Lessons From COVID and Its Predecessors. Home Med. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2022, 210, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, L.; Vera-Varela, C.; de la Vega, D.; Zelada, G.; Guija, J. Suicidal Behavior in the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Springer Nat. 2022, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón, S.; Carmona, J. Ideación y conductas suicidas en adolescentes y jóvenes. Rev. Pediatr. Aten Primaria 2018, 20, 387–397. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S113976322018000400014&lng=es (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis [PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses]. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero, V.; Izquierdo-Izquierdo, M.; Rodriguez, V.; Álvarez-Mon, M.; Lahera, G.; Santos, J.L.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. Dramatic increase of suicidality in children and adolescents after COVID-19 pandemic start: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 163, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pérez, L.; Cárdaba-García, I.; Madrigal-Fernández, M.; Montero, F.; Sobas, E.M.; Soto-Cámara, R. COVID-19 Pandemic Control Measures and Their Impact on University Students and Family Members in a Central Region of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, D.d.l.V.; Irigoyen-Otiñano, M.; Carballo, J.J.; Guija, J.A.; Giner, L. Suicidal thoughts and burnout among physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 321, 115057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Liso, R.; Portella, M.; Puntí-Vidal, J.; Pujals-Altés, E.; Torralbas-Ortega, J.; Llorens, M.; Pamias, M.; Fradera-Jiménez, M.; Montalvo-Aguirrezabala, I.; Palao, D.J. COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed the Psychiatric Profile of Adolescents Attempting Suicide: A Cross-Sectional Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villareal, K.; Peña, F.; Zamora, B.; Vargas, C.; Hernández, I.; Landero, C. Prevalence of suicidal behavior in a northeastern Mexican border population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 984374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, J.; Rivera-Rivera, L.; Astudillo-García, C.; Castillo-Castillo, L.; Morales-Chainé, S.; Tejadilla-Orozco, D. Social determinants associated with suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Bover, D.; Frader, M.; Carot-Sans, G.; Parra, I.; Piera-Jiménez, J.; Pontes, C.; Palao, D. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Incidence of Suicidal Behaviors: A Retrospective Analysis of Integrated Electronic Health Records in a Population of 7.5 Million. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavente-Fernández, A.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Torres-Parejo, Ú.; Morón, A.I.P.; Ontiveros, S.F.; García, D.V.; González-Domenech, P.; Ramos-Bossini, A.J.L. Psychological Impact and Risk of Suicide in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients, During the Initial Stage of the Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ullán, L.; de la Iglesia-Larrad, J.I.; Remón-Gallo, D.; Casado-Espada, N.M.; Gamonal-Limcaoco, S.; Lozano, M.T.; Aguilar, L.; Roncero, C. Increased incidence of high-lethality suicide attempts after the declaration of the state of alarm due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Salamanca: A real-world observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 312, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortier, P.; Vilagut, G.; Alayo, I.; Ferrer, M.; Amigo, F.; Aragonès, E.; Aragón-Peña, A.; del Barco, A.A.; Campos, M.; Espuga, M.; et al. Four-month incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among healthcare workers after the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miquel, C.; Domènech-Abella, J.; Felez-Nobrega, M.; Cristóbal-Narváez, P.; Mortier, P.; Vilagut, G.; Alonso, J.; Olaya, B.; Haro, J.M. The Mental Health of Employees with Job Loss and Income Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Perceived Financial Stress. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 19, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Santiago, R.; Valdez-Santiago, R.; Villalobos, A.; Villalobos, A.; Arenas-Monreal, L.; Arenas-Monreal, L.; González-Forteza, C.; González-Forteza, C.; Hermosillo-De-La-Torre, A.E.; Hermosillo-De-La-Torre, A.E.; et al. Comparison of suicide attempts among nationally representative samples of Mexican adolescents 12 months before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 298, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotomayor-Beltran, C.; Perez-Siguas, R.; Matta-Solis, H.; Jimenez, A.P.; Matta-Perez, H. Anxiety and fear of COVID-19 among shantytown dwellers in the megacity of lima. Open Public Health J. 2022, 15, e187494452210310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rivera, B.R.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Mendoza-Martínez, I.A.; Olguin-Tiznado, J.E.; García-Alcaráz, P.; Aranibar, M.F.; Camargo-Wilson, C. Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic Uncertainty in Negative Emotional States and Resilience as Mediators against Suicide Ideation, Drug Addiction and Alcoholism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Tirado, P.; Zanga-Pizarro, R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on mental health of the hospital front-line healthcare workers in Chile: A difference-in-differences approach. J. Public Health 2022, 45, e57–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosillo-de-la-Torre, A.; Arteaga-de-la-Luna, S.; Acevedo-Rojas, D.; Juárez-Loya, A.; Jiménez-Tapia, J.A.; Pedroza-Cabrera, F.J.; González-Forteza, C.; Cano, M.; Wagner, F.A. Psychosocial Correlates of Suicidal Behavior among Adolescents under Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Aguascalientes, Mexico: A Cross-Sectional Population Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortier, P.; Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Serra, C.; Molina, J.D.; López-Fresneña, N.; Puig, T.; Pelayo-Terán, J.M.; Pijoan, J.I.; Emparanza, J.I.; et al. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Psicogente 2021, 38, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, U.; León, Z.; Ceballos, G. Suicidal ideation, anxiety, social capital, and sleep among colombians in the first month of COVID-19-related physical isolation. Psicogente 2021, 24, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiarelli, N.; Eymann, A.; Ferraris, J. Current impact and future consequences of the pandemic on children’s and adolescents’ health. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2021, 119, e594–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortier, P.; Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Alayo, I.; Bruffaerts, R.; Cristóbal-Narváez, P.; del Cura-González, I.; Domènech-Abella, J.; Felez-Nobrega, M.; Olaya, B.; et al. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the Spanish adult general population during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz-Valdiviano, C.; Bazán-Ramírez, A.; Henostroza-Mota, C.; Cossío-Reynaga, M.; Torres-Prado, R.Y. Influence of loneliness, anxiety, and depression on suicidal ideation in peruvian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Gómez, P.; Martínez-López, J.; Gómez-Galán, J. Predictive factors of suicidal ideation in spanish university students: A health, preventive, social, and cultural approach. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Picón-Reátegui, C.K.; Zila-Velasque, J.P.; Grados-Espinoza, P.; Hinostroza-Zarate, C.M.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Pereira-Victorio, C.J. Suicide risk in military personnel during the COVID-19 health emergency in a peruvian region: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyor-Rodríguez, J.; Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Fernández-Prados, J.S. COVID-19 Fear, Resilience, Social Support, Anxiety, and Suicide among College Students in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Bertolín, S.; Segalàs, J.; Tubío-Fungueiriño, M.; Real, E.; Mar-Barrutia, L.; Fernández-Prieto, M.; Carvalho, S.R.; Carracedo, A.; Menchón, J. How is COVID-19 affecting patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder? A longitudinal study on the initial phase of the pandemic in a Spanish cohort. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; Jiménez-Ramón, E.; Garrote-Cámara, M.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Durante, A.; Júarez-Vela, R.; Santolalla-Arnedo, I. Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain: A Descriptive Analysis of the Published Documents. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapico, Y.; Pelayo, J.; Vega, S.; Garcia, M.; Landera, R.; Espandian, A. Changes in psychiatric emergencies during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in El Bierzo (Spain). Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Macêdo, D.; Costa, A.; Karina, R.; Ribeiro, A.; Leite, E.; Tolstenko, L. Suicidal behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical aspects and associated factors. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2022, 36, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiou, V.; Stefanou, M.; Siafakas, N.; Makris, M.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Spandidos, D.; Smyrnis, N.; Rizos, E. Suicidality and COVID-19: Suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviors and completed suicides amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen-Otiñano, M.; Nicolau-Subires, E.; González-Pinto, A.; Adrados-Pérez, M.; Buil-Reiné, E.; Ibarra-Pertusa, L.; Albert-Porcar, C.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Sánchez-Cazalilla, M.; Torterolo, G.; et al. Characteristics of patients treated for suicidal behavior during the pandemic in a psychiatric emergency service in a Spanish province. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2023, 16, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathirathna, M.; Nandasena, H.; Atapattu, A.; Weerasekara, I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicidal attempts and death rates: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaune, E.; Samuel, M.; Oh, H.; Poulet, E.; Brunelin, J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic rapid review. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.epdata.es/datos/cifras-suicidio-espana-datos-estadisticas/607 (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/indicadores/?ind=6200240526&tm=6#D6200240526#D6200240338 (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/ (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar/ (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Duarte, D. Suicidio e intentos de suicidio en los primeros 24 meses de pandemia por COVID-19 en Chile. Rev. Chil. Atención Primaria Y Salud Fam. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, P.; Armero, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, L.; García, J.; Bonet, C.; Notario, F.; Sánchez, A.; Rodríguez, P.; Díez, A. Self-harm and suicidal behavior in children and young people: Learning from the pandemic. An. Pediatría 2023, 98, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, R.; María Del Carmen, L. Health problems in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Cuba. Pediatría 2022, 94. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85167865165&origin=resultslist (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Farooq, S.; Tunmore, J.; Ali, W.; Ayub, M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalsman, G.; Stanley, B.; Szanto, K.; Clarke, D.; Carli, V.; Mehlum, L. Suicide in the Time of COVID-19: Review and Recommendations. Acad. Int. Investig. Suicidio (IASR) 2020, 24, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | SCOPUS | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (SUICIDAL AND IDEATION) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (COVID)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “FINAL”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “ALL”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “SPAIN”) OR LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “MEXICO”) OR LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “ARGENTINA”) OR LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “PERU”) OR LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “COLOMBIA”) OR LIMIT-TO (AFFILCOUNTRY, “CHILE”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2023) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “AR”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “MEDI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “PSYC”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (EXACT KEYWORD, “SUICIDAL IDEATION”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACT KEYWORD, “COVID-19”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACT KEYWORD, “PANDEMIC”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “ENGLISH”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “SPANISH”)) |

| 02 | Web of Science | Results for SUICIDAL IDEATION (All Fields) AND COVID (All Fields) and Open Access and 6.24 Psychiatry & Psychology or 1.21 Psychiatry (Citation Topics Meso) and 1.21.430 Suicide (Citation Topics Micro) and 2020 or 2023 or 2021 or 2022 (Publication Years) and Article or Review Article (Document Types) and Psychiatry or Psychology Multidisciplinary or Psychology Clinical or Medicine General Internal or Psychology (Web of Science Categories) and All Open Access (Open Access) and SPAIN or ARGENTINA or COLOMBIA or MEXICO or PERU (Countries/Regions) and English or Spanish (Languages) |

| 03 | ProQuest Coronavirus Research Database | Searched for: (SUICIDAL IDEATION AND COVID) AND (location.exact (“Spain” OR “Mexico” OR “Peru” OR “Chile” OR “Colombia” OR “Argentina”) AND at.exact (“Article”) AND subt.exact (“COVID-19” OR “suicides & suicide attempts”) AND la. Exact (“ENG”) AND PEER (yes)) Database: Coronavirus Research Database Results: 123 |

| No. | Excel Matrix Code | Title | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Dramatic increase of suicidality in children and adolescents after COVID-19 pandemic start: A two-year longitudinal study [30] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.04.014 |

| 2 | 4 | Suicide attempt before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study from the emergency department [19] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semerg.2023.101922 |

| 3 | 6 | COVID-19 Pandemic Control Measures and Their Impact on University Students and Family Members in a Central Region of Spain [31] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054470 |

| 4 | 7 | Suicidal thoughts and burnout among physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain [32] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115057 |

| 5 | 8 | COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed the Psychiatric Profile of Adolescents Attempting Suicide: A Cross-Sectional Comparison [33] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042952 |

| 6 | 10 | Prevalence of suicidal behavior in a northeastern Mexican border population during the COVID-19 pandemic [34] | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.984374 |

| 7 | 12 | Social determinants associated with suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico [35] | https://doi.org/10.21149/13744 |

| 8 | 14 | Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Incidence of Suicidal Behaviors: A Retrospective Analysis of Integrated Electronic Health Records in a Population of 7.5 Million [36] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114364 |

| 9 | 17 | Psychological Impact and Risk of Suicide in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients, During the Initial Stage of the Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study [37] | https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000974 |

| 10 | 21 | Increased incidence of high-lethality suicide attempts after the declaration of the state of alarm due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Salamanca: A real-world observational study [38] | https://doi.org/0.1016/j.psychres.2022.114578 |

| 11 | 22 | Four-month incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among healthcare workers after the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic [39] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.02.009 |

| 12 | 25 | The Mental Health of Employees with Job Loss and Income Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Perceived Financial Stress [40] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063158 |

| 13 | 29 | Comparison of suicide attempts among nationally representative samples of Mexican adolescents 12 months before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic [41] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.111 |

| 14 | 31 | Anxiety and Fear of COVID-19 among Shantytown Dwellers in The Megacity of Lima [42] | https://doi.org/10.2174/18749445-v15-e221026-2022-69 |

| 15 | 34 | Influence of COVID-19 pandemic uncertainty in negative emotional states and resilience as mediators against suicide ideation, drug addiction and alcoholism [43] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412891 |

| 16 | 39 | Impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on mental health of the hospital front-line healthcare workers in Chile: a difference-in-differences approach [44] | https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac008 |

| 17 | 42 | Psychosocial correlates of suicidal behavior among adolescents under confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Aguascalientes, Mexico: A cross-sectional population survey [45] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094977 |

| 18 | 43 | Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak [46] | https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23129 |

| 19 | 47 | Suicidal ideation, anxiety, social capital, and sleep among Colombians in the first month of COVID-19-related physical isolation [47] | https://doi.org/10.17081/psico.24.45.4075 |

| 20 | 48 | Current impact and future consequences of the pandemic on children’s and adolescents’ health [48] | http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2021.eng.e594 |

| 21 | 50 | Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the Spanish adult general population during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic [49] | https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000093 |

| 22 | 2 | Influence of Loneliness, Anxiety, and Depression on Suicidal Ideation in Peruvian Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic [50] | https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043197 |

| 23 | 3 | Predictive Factors of Suicidal Ideation in Spanish University Students: A Health, Preventive, Social, and Cultural Approach [51] | https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031207 |

| 24 | 7 | Suicide Risk in Military Personnel during the COVID-19 Health Emergency in a Peruvian Region: A Cross-Sectional Study [52] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013502 |

| 25 | 24 | COVID-19 Fear, Resilience, Social Support, Anxiety, and Suicide among College Students in Spain [53] | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158156 |

| 26 | 42 | How is COVID-19 affecting patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder? A longitudinal study on the initial phase of the pandemic in a Spanish cohort [54] | https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2214 |

| 27 | 53 | Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain: A Descriptive Analysis of the Published Documents [55] | https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12010009 |

| 28 | 54 | Changes in psychiatric emergencies during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in El Bierzo (Spain) [56] | https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.658 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valle-Palomino, N.; Fernández-Mantilla, M.M.; Talledo-Sebedón, D.d.L.; Guzmán-González, O.V.; Carguachinchay-Huanca, V.H.; Sosa-Lizama, A.A.; Orlandini-Valle, B.; Vela-Miranda, Ó.M. Suicidal Ideation and Death by Suicide as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spanish-Speaking Countries: Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216700

Valle-Palomino N, Fernández-Mantilla MM, Talledo-Sebedón DdL, Guzmán-González OV, Carguachinchay-Huanca VH, Sosa-Lizama AA, Orlandini-Valle B, Vela-Miranda ÓM. Suicidal Ideation and Death by Suicide as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spanish-Speaking Countries: Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(21):6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216700

Chicago/Turabian StyleValle-Palomino, Nicolás, Mirtha Mercedes Fernández-Mantilla, Danae de Lourdes Talledo-Sebedón, Olinda Victoria Guzmán-González, Vanessa Haydee Carguachinchay-Huanca, Alfonso Alejandro Sosa-Lizama, Brunella Orlandini-Valle, and Óscar Manuel Vela-Miranda. 2023. "Suicidal Ideation and Death by Suicide as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spanish-Speaking Countries: Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 21: 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216700

APA StyleValle-Palomino, N., Fernández-Mantilla, M. M., Talledo-Sebedón, D. d. L., Guzmán-González, O. V., Carguachinchay-Huanca, V. H., Sosa-Lizama, A. A., Orlandini-Valle, B., & Vela-Miranda, Ó. M. (2023). Suicidal Ideation and Death by Suicide as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spanish-Speaking Countries: Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(21), 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216700